It’s 20 years since VFL Park and Victoria Park vanished from footy

One was a cauldron of hatred for the opposition, while the other was a freezing concrete bowl in the middle of a paddock with no public transport. But love or loathe them, Victoria Park and Waverley Park brought footy to the suburbs.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s 20 years this since two of the AFL’s most famous grounds fell silent.

One was a brick cauldron of hatred where oppositions feared to tread.

The other was an ill-conceived concrete bowl that once hosted a grand final and the rebel competition that split the game of cricket in the 1970s, but was hard for supporters to love.

Waverley Park, the former VFL Park, was a bold step into the future for the Victorian Football League — a bid to bring the great game to the people as Melbourne spread southeast.

It was a big, modern rival to the MCG — and that ultimately caused its demise.

The idea was first mooted in 1959. In 1962, the league bought an 86ha grazing and market garden block in Mulgrave, beside a proposed freeway that was expected to link the area directly to the city.

Work began in January 1966, with VFL President Sir Kenneth Luke turning the first sod.

It was a vast undertaking that required the excavation of almost 300,000 cubic metres of soil. Much of it formed banks on which the grandstands were construction.

What it lacked in public transport it made up for with acres of parking.

VFL Park was partly completed when it hosted its first VFL game — a match between Fitzroy and Geelong — on April 18, 1970. For the record, 27,557 people watched the Cats trounce the Lions by a lazy 61 points.

The ground was the largest in the VFL, but only one stand — the K.G. Luke stand, had been completed. The rest, all 19km of terraces circling the ground and a car park expansion for up to 25,000 vehicles, weren’t finished until 1974.

VFL Park held its first final in 1972, when 52,499 people saw St Kilda defeat Essendon by 53 points in the elimination final.

But it wasn’t until after the 1974 season that the Mulgrave Freeway was built past the ground inbound to Springvale Rd, and while the car park was huge, even with the freeway, roads leading to the ground became clogged on game days.

The VFL lobbied the State Government to extend the Glen Waverley line to VFL Park, but it never happened.

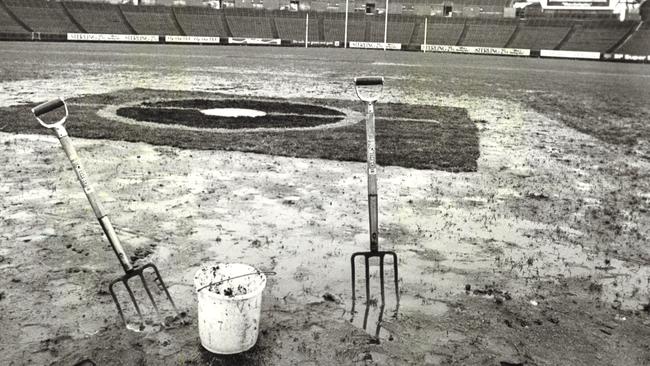

And many of the stands weren’t covered. In the wide-open spaces of the rain belt in the southeast, winter weather was often unkind.

Footy caller Rex Hunt later dubbed the ground Arctic Park, and the moniker stuck.

Development continued. Light towers were completed in May 1977, allowing for the first night game between Fitzroy and North Melbourne in the Amco-Herald Cup.

But the lights went out 10 minutes before the game when a fuse blew on a power pole, and the ground was in total darkness during the repair.

The game got underway almost an hour late.

The lights failed again in a match between Essendon and St Kilda in 1996. The crowd invaded the ground, forcing its completion three days later.

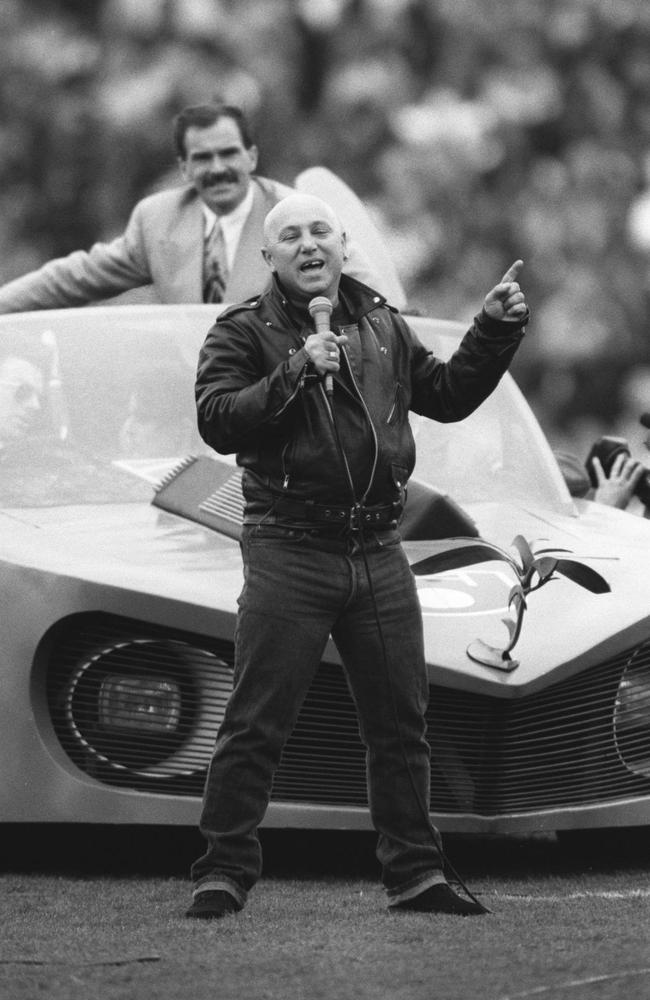

VFL Park played host to Supertests and one-day games for Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket and was a concert venue for acts including Kiss, U2, Rod Stewart and David Bowie.

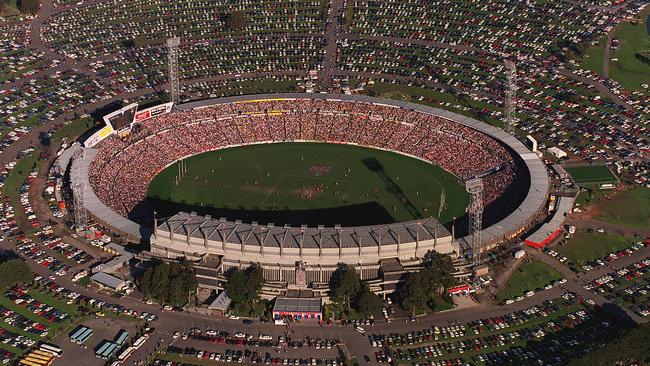

Its peak crowd was 92,935 for the Queen’s Birthday 1981 clash between Collingwood and Hawthorn. The Hawks got up by 46 points.

There were plans in the early 1980s to expand VFL Park to a capacity of 157,000 with the aim of having the stadium host the 1984 grand final.

It even gained a monochrome scoreboard screen for replays, but pressure from the state government and the Melbourne Cricket Club forced a rethink.

The VFL wanted to control the home of footy, but couldn’t because of the MCC, and factors such as the government’s refusal to extend the railway line to the ground and ease its public transport woes.

It was bitterly disappointing to the league.

“There was just so much politics,” then-VFL president Allen Aylett told the Herald Sun in 2009.

“People say Waverley was an iceberg and was never popular; it was popular, but it was never given a good go.”

Hawthorn took on Waverley as its home ground in 1990.

The reconstruction of the MCG’s Southern Stand from the late ’80s gave VFL Park (by then, Waverley Park) one of its greatest days — the 1991 grand final — and also spelled the end for Waverley.

By 1999, the AFL sealed its fate, announcing plans to demolish the ground and sell the land for residential development. It sold in 2002 for $110 million. The sale helped fund the new Docklands ground.

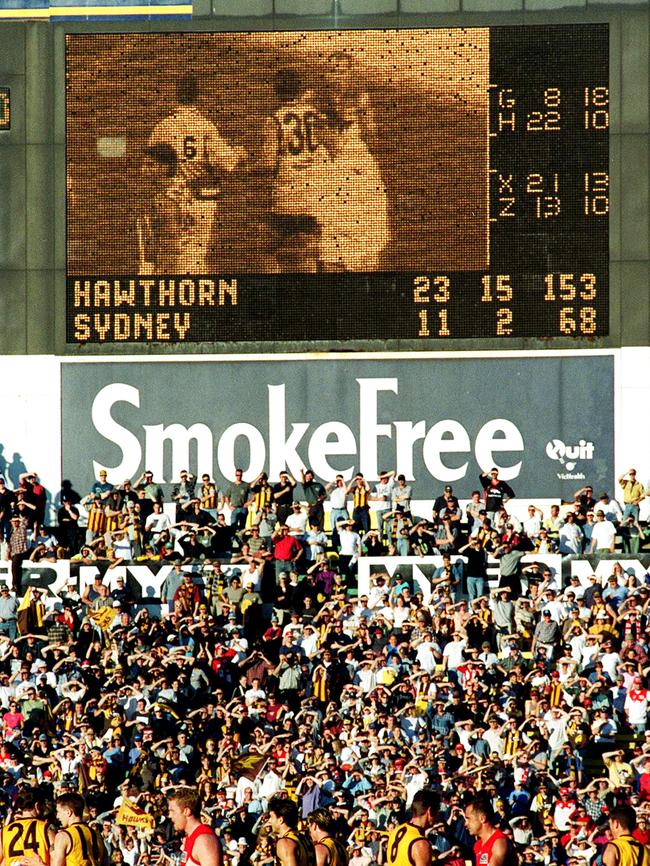

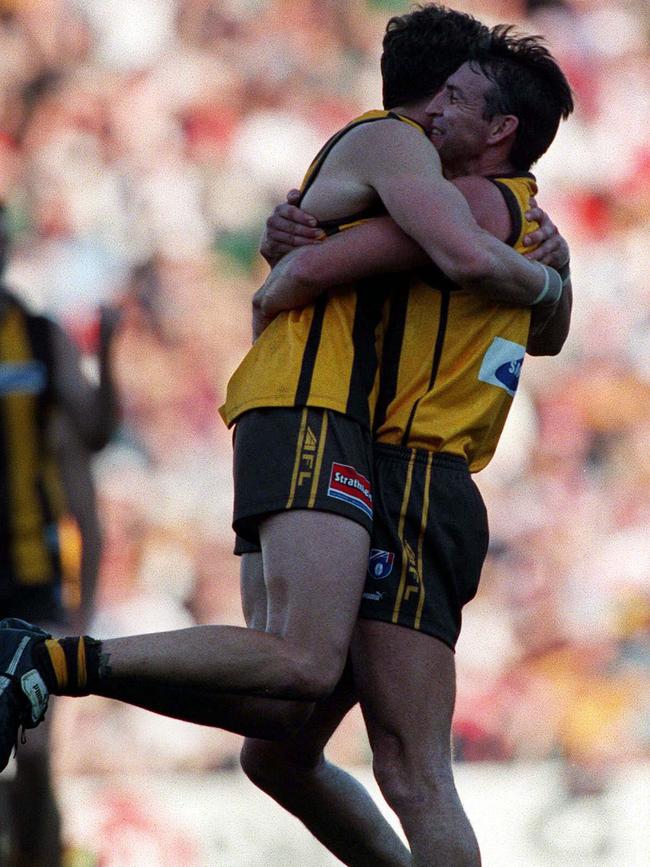

After 732 VFL/AFL games, Hawthorn farewelled Waverley with a thumping 85-point win over Sydney before a sellout crowd of 72,135, 20 years ago today — August 29, 1999.

A heritage listing prevented the demolition of the K.G. Luke Stand. The ground and stand remain Hawthorn’s training and administrative base.

VICTORIA PARK’S SWAN SONG

The demise of Waverley Park wasn’t the only AFL swan song on that weekend in 1999.

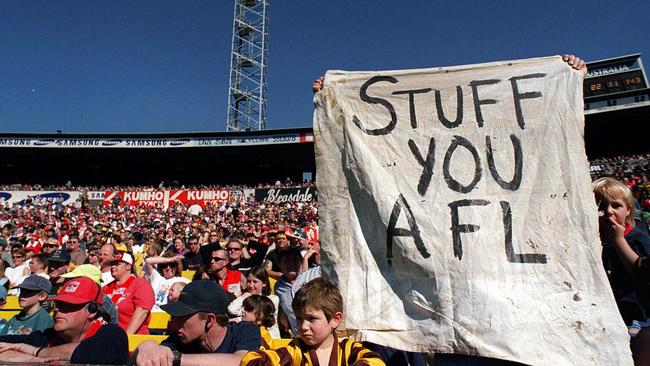

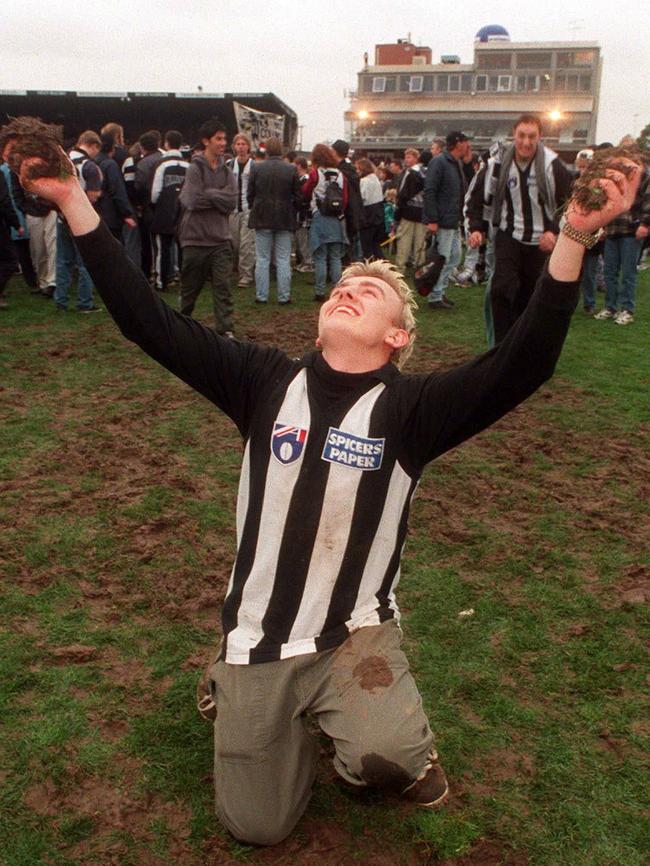

The Magpie Army sent off Victoria Park in typically exuberant fashion the day before.

The ground was established as early as 1880 and served as Collingwood’s home ground from 1892 to 1999, and as its administrative base until 2005.

The Magpies formed from a groundswell of support from the people of Collingwood and the backing of the Collingwood Council, which knocked up the first stand at Victoria Park in the team’s foundation year, 1892.

The Ladies’ and Members’ stands followed during the first decade of the 1900s as the Magpies established themselves as the power side of the freshly minted VFL.

Like the modern Geelong, Collingwood at Victoria Park became near invincible. The Collingwood faithful had a reputation for being among the toughest crowd in the league.

The Jack Ryder Stand replaced the Ladies Stand in 1929. The club was heading towards its legendary four premierships in a row as the Great Depression hit hard in heavily-industrial Collingwood.

The Magpies’ dominance and the club’s initiative to admit sustenance workers (those men in a Depression-era work for the dole program) free of charge to Collingwood games helped build a tribal bond with fans.

Victoria Park was the home ground other teams feared. Captain Blood Jack Dyer, a copper and one of the hardest men ever to take the field for Richmond, once described his debut match at Victoria Park as “the first wave of sustained hate I have ever experienced”.

Victoria Park achieved its biggest crowd in Round 2, 1948, when the Magpies beat South Melbourne by 53 points.

The club was able to strike a deal with the Collingwood council in the 1950s, that gave it long-term control of the ground and the certainty to develop Victoria Park.

Over the next decade, the R.T. Rush Stand, the Sherrin Stand and the social club, now the Bob Rose Stand, were constructed.

The 1970s Victoria Park continued the cauldron motif the Magpies had crafted for decades.

The visitors’ race came out of the Sherrin Stand, which was filled every game with a seething mob of one-eyed Magpies.

The visitors’ bench was right in front of the social club — no respite there. And once the opposition had been flogged, there was no comfort in the changerooms either.

MORE NEWS

WHY DID AA SELECTORS LEAVE THESE GUNS OUT?

HOW ‘EVERY DOG HAS HIS DAY’ CALL SPARKED FOOTY CHAOS

The club’s control of the ground lasted well into the 1990s — and into the era when the AFL was phasing out suburban grounds.

The team had already shifted some home games to VFL Park and the MCG.

And with a legal capacity of around 25,000, there was no way that Collingwood could make Victoria Park financially viable.

Sadly for the Magpies, they couldn’t leave Victoria Park on a winning note.

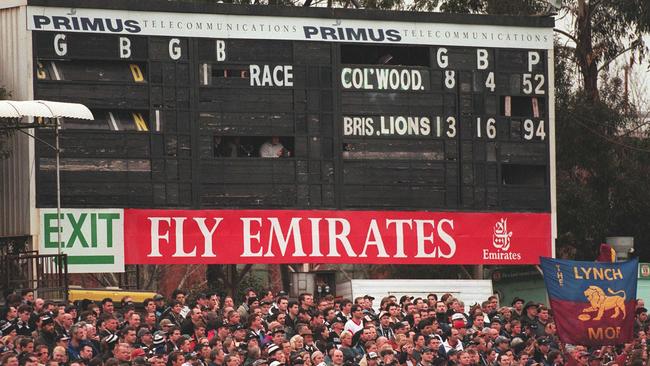

They went down to Brisbane by 44 points before24,493 fans, virtually every one of them bleeding black and white.

The old ground has been returned to the community. Many of the stands, terraces and walls around the ground have been removed to open up Victoria Park for public use.