Insiders spill the beans on Labor campaign funding rort

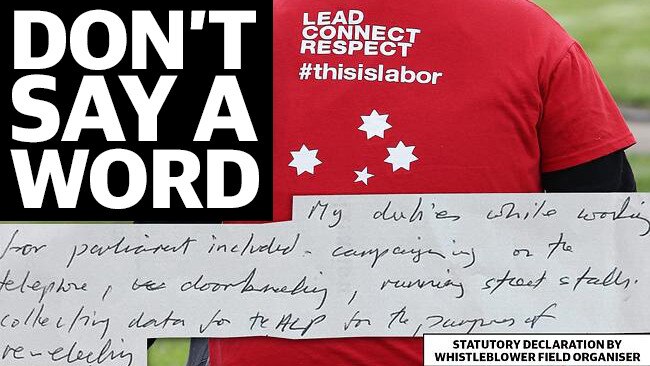

“WE were told ‘shut your mouth’ about the way we were being paid — if that is not a clear sign that it is dodgy, then I don’t know what is.’’

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“WE were told ‘shut your mouth’ about the way we were being paid — if that is not a clear sign that it is dodgy, then I don’t know what is.’’

It was March 2014, and 26 young Labor idealists were gathered in a nondescript office in William St, in Melbourne’s CBD.

The group were informed they were being hired to be the shock troops of a Labor campaign that would make history by winning back government after only four years. It should have been a moment to recall with undiluted pride.

But two of the troops have broken ranks to independently detail misgivings about what they were told in the training program, how they were paid and what went on in the campaign shadows.

JAMES CAMPBELL: SCANDAL DEMANDS INVESTIGATION

They spoke to the Herald Sun separately after being contacted for comment.

On that first day of training on how to recruit and motivate ALP volunteers for the party’s Community Action Network, Daniel Andrews himself was present to stress how important they would be to Labor’s chance of victory.

Also there were ALP assistant state secretary Stephen Donnelly, and John Lenders, the party’s leader in the Upper House at that time.

And for young Labor recruits, it was exciting to be working with American Sam Schneidman — hired from the Obama campaign.

RORTS FOR VOTES IN LABOR ELECTION FUNDING SCANDAL

The new troops, called Field Organisers (FOs), had been interviewed months earlier by Mr Donnelly and fellow assistant state secretary Kosmos Samaras.

“They were after people with sort of a Labor story and the ability to recruit people who could sell the campaign to potential volunteers and big groups,” one whistleblower recalls.

They were made a fulltime job offer by Mr Donnelly, to work for the ALP until the November election. They would be paid about $35 an hour — equivalent to $63,000 a year.

But the keen Labor kids wouldn’t be working for the party fulltime.

“Lenders walks in with (his staffer) Jadon Mintern and essentially starts saying how important the campaign is in the field,” one FO said.

“And then starts with, ‘Oh, by the way, this is how you are going to be paid’.’’

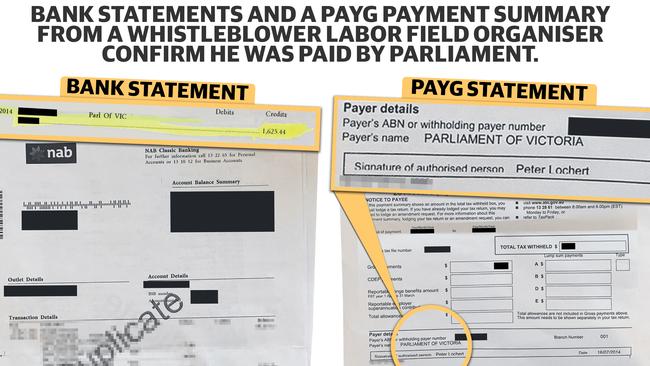

“So 60 per cent of your wage or three days a week is coming from the party and two days a week you are working for the Parliament of Victoria.

“Definitely, none of us knew we were being employed by the Parliament of Victoria until John Lenders walked in and said, ‘By the way, you’re also going to be employed by the Parliament of Victoria two days a week’.”

The Labor idealists were not impressed.

“Immediately someone asked ‘Is that legal?’ And he said — to the best of my recollection — ‘It’s a fine line but we think it’s legal. It’s OK. Don’t worry about it’.’’

A second FO remembers the same.

“It was practically the first order of business,” he said.

“They made it clear that this was how we were being paid and don’t say anything about it … John Lenders said he didn’t want people sniffing round.”

His colleague agreed: “We were also told, ‘If people ask, you are just employed by the party’.’’

They were told not to contact their employer, Parliamentary Services, but to talk to a staffer if they had problem.

“People were looking at each other,” one of the whistleblowers said.

Both FOs remember it was Mr Lenders who told them not discuss their employment arrangements.

“We were told, ‘Shut your mouth about the way we were being paid’ — if that is not a clear sign that it is dodgy, then I don’t know what is,” one said.

After lunch the first day, recruits returned to find sign-up packs for their employment by the ALP and the Parliament.

Both FOs say that for their electorate officer positions, they filled in blank time sheets to last several months.

Then the group was free to begin training, starting with trust games.

One game included passing around a talking stick.

In another, they were blindfolded and told to find others in the group making farm noises, including mooing, to guide them.

Other sessions taught doorknocking and phone banking techniques.

They were given scripts on how to “tell their Labor story” to the public to convince them to join as volunteers.

On the final day, party deputy leader James Merlino presented certificates.

The next week, the FOs were sent into the field to begin recruiting volunteers.

While they were based in electorate offices, there was no pretence they were doing electorate office work. Often, they weren’t even in the office of the MP who signed their timesheets.

Some FOs even complained they were made to feel unwelcome in offices they were assigned to by the MPs’ “real” electorate officers.

The job of the FOs was to make contact with as many Labor supporters as they could, asking them to donate their time to the campaign.

Mostly, they worked off lists of numbers generated in the party’s Docklands HQ. Potential volunteers were pushed to fill in what were called #thisislabor cards.

“Essentially they are a red card with just #thisislabor on it and have a small white strip where people put down their name, phone number, where they live, email address,” one FO said.

“They get to take the red part, we keep the other part for list building. Usually you only offer these to people who seem like they want to support Labor and want to get involved on the campaign.’’

Each FO was given 10 Nokia phones to use when conducting phone banks.

“We referred to them as burners. They were cheap — 30 bucks a month for unlimited calls,” one said.

Each day started with a conference call with their seats’ regional director. Like all sales teams, they began with numbers from the previous day.

“We talked about the plan for the day and how many volunteer recruitment calls were made the day before,” one FO said.

“You had to give your numbers, it was very competitive.’’

At the end of the week, each region would call in to the directors. Some say the pressure was intense — more like working for Amway or Herbalife than conventional political campaigning.

More serious concerns, though, remained over the scheme’s integrity. FOs were told by MPs not to wear campaign shirts in electorate offices.

At least two MPs refused to hand over their budgets. Others demurred but eventually agreed to participate.

When the Herald Sun revealed MPs’ worries about the program, the word went out that FOs were to keep quiet.

Within hours of the Herald Sun contacting FOs, they received messages telling them not to talk.

Since then, Twitter accounts have been locked and LinkedIn accounts deleted.

Two so far have made it clear they are not going to lie to cover up for something they were told was legal.