Inside the gilded doors of a Melbourne icon

The Federal Hotel and Coffee Palace was one of the most beautiful buildings in the Marvellous Melbourne of the 1880s. Less than 90 years later, it fell to a wrecking ball.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A new office building planned for the corner of Collins and King streets in the city may offer a reflection of the grand Victorian-era hotel that used to be there.

It’s a lovely idea but, of course, it can never replace the real thing.

The building that used to occupy the site, the Federal Hotel and Coffee Palace, survived less than 90 years before it was felled in 1973.

The Federal Hotel and Coffee Palace was one of Melbourne’s most elaborately designed and luxurious hotels, a showpiece befitting 1880s Melbourne, the world’s richest city, which was basking in the glow of the gold rush and the land boom that followed.

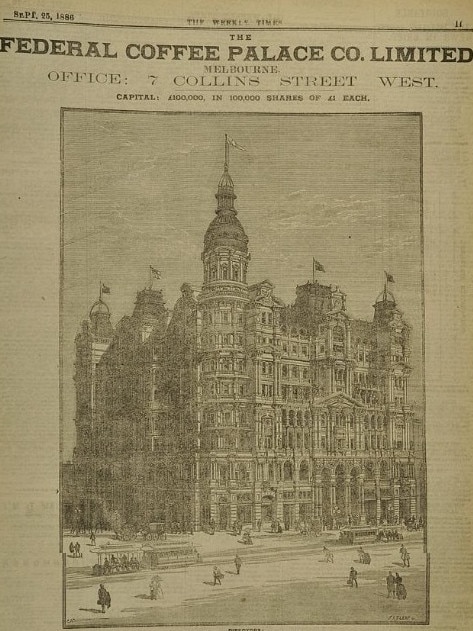

Melbourne businessmen James Munro, who served as Premier from 1890 to 1892, and James Mirams, both prominent members of the temperance movement, established the Federal Coffee Palace Company in 1885 and sought to raise £100,000 with a £1 share issue.

Munro was also involved in the Grand Hotel (later, the Windsor), and the Victoria Coffee Palace, two of the larger temperance venues in Melbourne.

The Federal Hotel site was a block from both Spencer St Station and the docks on the north side of the Yarra, and was convenient for travellers looking for luxurious place to stay.

The company held a design competition for their showpiece hotel. It was won by WH Ellerker, EG Kilburn and William Pitt.

They designed what would be Australia’s largest and most well appointed hotel once it opened in 1888.

Construction took an astounding five million bricks and cost £90,000. It took another £20,000 to furnish the 370-bedroom, seven-storey hotel.

Its grand entrance on Collins St was lined with statues, cherubs and columns, and led into an opulent lobby that rose four floors and featured a glass ceiling.

Off the lobby, there was a spacious dining room, a coffee bar, a billiards room and a main staircase made from white and red marble, concrete and decorative brass panels.

There were three passenger and three goods lifts and a fireproof staircase.

The first floor boasted dining rooms for families and just for ladies, a bridal chamber with dressing rooms and a bath, closets, reading rooms, smoking rooms, sitting rooms, bedrooms, bathrooms, managers’ offices, chess rooms and a balcony facing King and Collins streets.

Upper levels contained bedrooms, bathrooms, closets and sitting rooms for guests to enjoy.

A promenade on the roof allowed visitors to see the sights of the city, with access to the highest point of the building – the dome at the top of the turret at the corner of the building.

A blue light was placed on the top of the dome’s flagpole as a guide to ships in the bay.

The Federal was so large that it blocked the view to the beacon on Flagstaff Hill, a few blocks to the north.

The basement was the centre of the hotel’s operation. It concealed the engine room and boiler room, a big kitchen with added food preparation areas and a vast pantry, a bakery, a wine cellar and an ice-making machine.

The walls contained 8km of gas pipes and 7km of electric wiring to work the guests’ bell system.

Coffee palaces were a 19th century phenomenon that was imported from England, a device that aimed to drive patrons away from seedy gin outlets in London.

Here in Victoria, they were an alternative to the boozy and raucous culture of hotels of the day, especially in the goldfields.

The term “coffee palace” was a signal to the world that grog was not on the menu.

But alcohol, or the lack of it, proved a stumbling block to many city temperance hotels.

Those patrons that weren’t slipping out to whet their whistles at pubs nearby were smuggling liquor in to enjoy in the privacy of their rooms at the Federal.

And in the tough economic conditions caused by the 1890s depression that busted the 1880s land boom, it proved too much to bear.

Both the Grand and the Federal Hotel and Coffee Palace were granted liquor licences in 1897.

The Federal dropped “coffee palace” from its moniker and was renamed the Federal Palace Hotel.

For many years, the hotel was a favourite for business and society events.

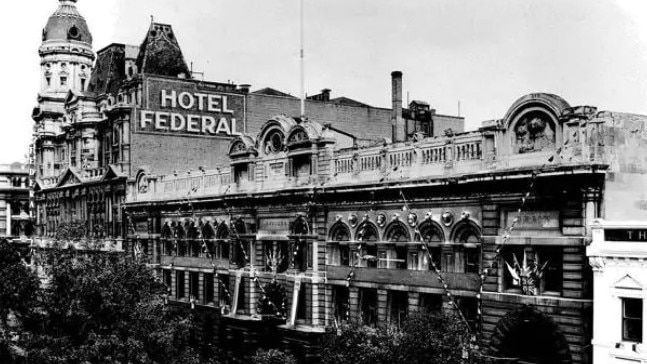

Following some renovations, the hotel was renamed the Federal Hotel in 1923.

While it was every bit as luxurious as the Grand (Windsor) at the other end of the city, it was perhaps not as fashionable because of its location.

The King St corner is a long way from the Paris end of Collins St, and as the years went on, the west end of the CBD became more industrial and a bit grimy.

Just up the road, at the corner of Collins and William streets, the Western Market was regarded as the most run down of Melbourne’s markets, and the Federal itself was surrounded by warehouses and shipping agents, and its exterior became stained by soot over the years.

By the 1960s, the Federal was well out of favour.

The construction of the Kings Way flyover in 1961 only made the area less attractive. For the first time, King St crossed the Yarra and turned the once quiet street into a thoroughfare that carried the Princes Hwy right past.

In 1967, man about town Peter Janson moved into the tower at the top of the hotel. It had never been occupied, but Janson chose it as his bachelor pad.

This coincided with renovations that, sadly, couldn’t save the ageing hotel.

Janson stayed four years until the hotel was sold by Federal Hotels Pty Ltd to a developer in 1971.

By then, the hotel was poorly patronised.

With the Western Market already replaced by the National Mutual Building and buildings in other parts of the CBD’s southwestern corner being redevelopment, the Federal Hotel’s time had come despite an intensive public campaign to save it.

The hotel closed in February 1972, and thousands of people looked on when that famous facade came down in 1973.

MORE NEWS

NORTHCOTE HIGH DUMPS JOHN BATMAN FROM SCHOOL’S HOUSES

UNI’S WOMEN-ONLY PROMOTION SEMINARS SLAMMED

DECISION TO AXE HOLDEN HEARTBREAKING BUT NO SURPRISE

By 1975, the 23-storey concrete office tower Enterprise Tower rose in its place.

Now, the Federal Hotel site is to be renewed again with a $1.5 billion, 34-storey office block to be developed by Charter Hall.

If approved by the Melbourne City Council, the exterior of the lower levels will feature a design that emulates the intricate facade of the old Federal Hotel.