Idyllic Yallourn was swallowed by the coal mine it was built to serve

IT was dubbed a workers’ paradise, but what may have been Victoria’s best town survived only 60 years. Meet Yallourn, the town that powered Victoria.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT was a company town, but for many it was so much more.

Brown coal was both its reason for being and the cause of its death but Yallourn was no grimy, ramshackle, utilitarian mining settlement.

The State Electricity Commission looked after every detail and planned Yallourn — a word created from two indigenous words meaning “brown fire” — to ensure SEC workers and their families had every comfort and, decades after it was demolished, Yallourn is still revered among former residents still living in the Latrobe Valley.

Yallourn and the State Electricity Commission were the vision of founding SEC chairman Sir John Monash, an engineer by trade and the heroic Australian World War I commander.

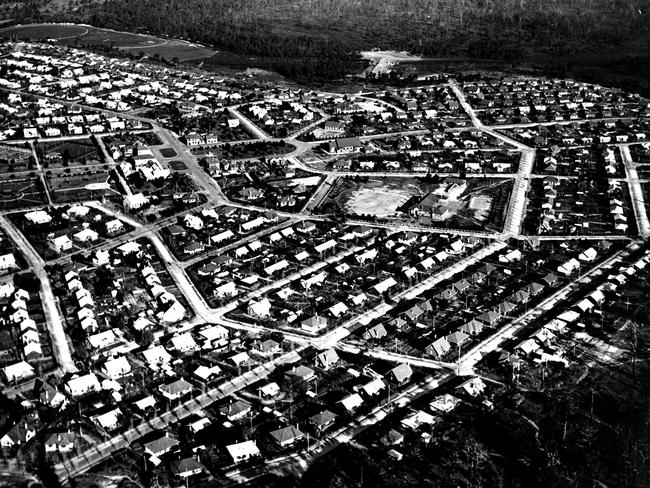

Monash turned the first sod at the Yallourn Open Cut Mine in 1920 and set about building a model town for mine and power station workers based on the British notion of “garden city” factory towns.

A saw mill, a quarry and a factory to churn out bricks and roof tiles were built under Monash’s direction.

The town, planned by the SEC’s architect, A.R. La Gersch, was set high in the Haunted Hills, between Moe and Morwell, with a commanding view of the Latrobe Valley (then just a series of pastoral settlements) and walking distance from the mine and the original Yallourn power station.

The flow of electricity from Yallourn was a momentous occasion in Victorian history.

It gave the state the base load electricity capacity to enable the state to become Australia’s industrial powerhouse.

It transformed Victoria’s economy, creating jobs and promoting development on a scale not seen since the 1850s gold rush.

Monash declared that Yallourn house blocks should be no less than a quarter acre (just over 1000 square metres) — large enough, he decreed, for residents to have a garden and keep a horse.

There was no local government, although by 1947 a Town Advisory Council advised the SEC on local issues.

Monash died in 1931, before his vision for the SEC and Yallourn were realised.

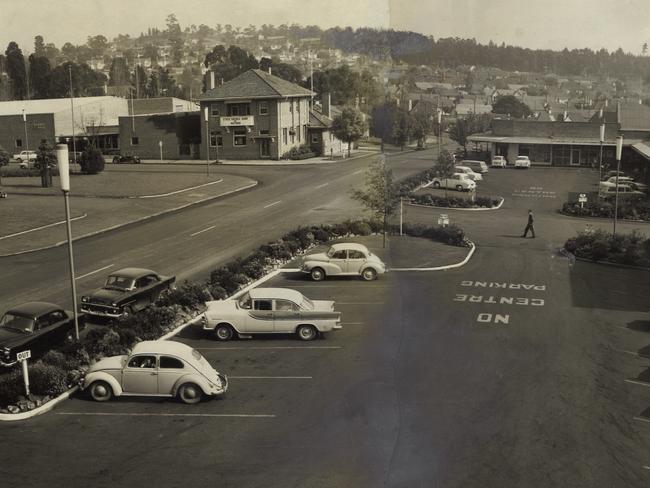

Yallourn grew around Monash Square, named in his honour and with a monument to him in the centre.

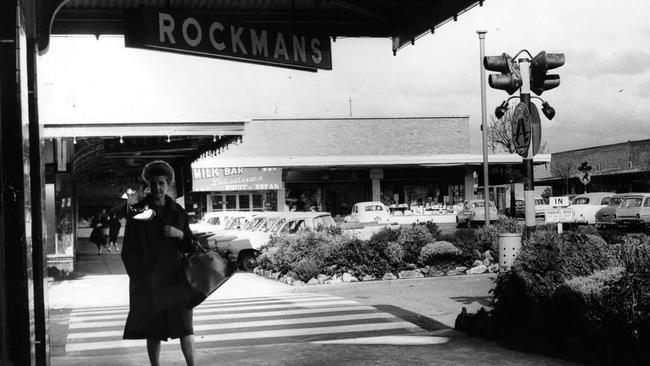

The main street, Broadway, linked the square, the commercial precinct around it and the railway station.

In lieu of a local government, SEC gardeners maintained Yallourn’s public centres and its renowned sports grounds.

Like any country town, sport was the lifeblood of Yallourn, but the high quality facilities built and maintained by the SEC for football, cricket, tennis, croquet, lawn bowls, basketball, netball, soccer and hockey helped foster a close community.

The town also had its own swimming pool and a lake for rowing.

The imposing SEC headquarters in Yallourn had rendered columns and a manicured garden.

The Yallourn Theatre, an art deco gem, was once the largest theatre outside Melbourne.

Yallourn had churches, a pub, a primary school, a technical school, a high school and a bus terminal.

Brick and weatherboard houses, many with distinctive local terracotta roof tiles, were constructed around town to a small selection of varied designs.

The SEC, which owned all the land and almost all of Yallourn’s buildings, charged rents below the market rate.

A plant nursery grew the thousands of deciduous trees that lined the streets and shaded Yallourn’s parks and gardens.

Those maples, poplars and other varieties drew visitors to Yallourn when the fiery reds and glowing golds of autumn appeared.

Yallourn grew into a town of about 5000 people at its peak in the 1960s.

It was surrounded by a green belt of trees, open parks and sports grounds and offered services and facilities that were the envy of virtually every community in Victoria.

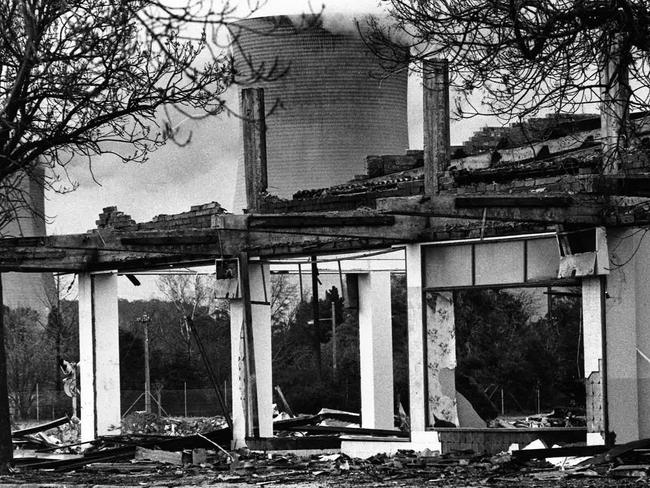

But in 1961, the SEC first announced its intention to demolish the town by 1990 to make way for an expansion of the coal mine.

Officially, the SEC said the mine expansion was necessary.

In 1967, it opened the larger Yallourn W power station.

But some have speculated that with debts and costs rising, the SEC was no longer willing to be both an employer and a landlord, and wanted to close the town to force the residents to move.

The decision caused protest and heartache for the people of Yallourn but, as landlord, the SEC had no doubt its plan would prevail.

A 1974 documentary about Yallourn produced by the SEC was titled Born To Die.

Years later, the Yallourn Association’s film on the dying days of the town was called Tears In The Coal Dust.

The first homes were relocated from Yallourn to other Latrobe Valley towns in the early 1970s, with a few shifted further afield.

Newborough, a new suburb on the Yallourn side of Moe, expanded to house some of the people shifting from Yallourn with their old houses.

By 1981, Yallourn was a virtual ghost town and the demolition proceeded in earnest.

Most of the town site was swallowed by the mine in the 1990s.

Groups including the Yallourn Association and the Old Brown Coal Mine Museum in Yallourn North, a few kilometres from the site of old Yallourn, are dedicated to preserving the town’s history and keeping memories alive of a happy home.

The Yallourn Old Girls Association even has an interactive map and 3D “Virtual Yallourn” online, detailing the histories of almost every building and home in town and including house plans and a wide variety of historic images and documents.

Go here to buy a DVD copy of Tears In The Cold Dust, along with other films and memorabilia.