How the Royal Children’s Hospital and Good Friday Appeal began

Every year Victorians unite to raise money for sick children on Good Friday. Today, on the 93rd Good Friday Appeal, we explore the closely linked histories of the fundraiser and children’s hospital.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

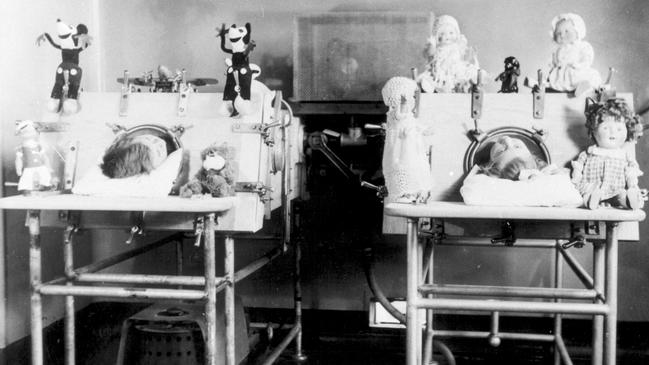

Up to 40 beds filled each ward, visitors were all but banned, and sick kids were knocked out with a chloroform cloth over their face.

The fascinating history of both the Royal Children’s Hospital and the Good Friday Appeal are explored in a special three-part miniseries of the free In Black and White podcast:

Melbourne historian Peter Yule detailed the history of the RCH for his incredible book, The Royal Children’s Hospital: A History of Faith, Science and Love.

The RCH was Australia’s first children’s hospital when it was founded in 1870, at a time when about 20 per cent of babies didn’t live to the age of one.

“Before the 1860s, there was actually very little point in sending children to hospital, because fundamentally children were better off at home than in hospitals at that time because they were unhygienic,” Dr Yule says.

“They had no trained nurses, medicine could offer no treatments for most diseases, and the mortality from any surgery they had without anaesthetics or antiseptics was very high.”

“But in the 1850s and 1860s, there were enormous breakthroughs in medicine. The introduction of anaesthetics and antiseptic techniques revolutionised surgery so that the chances of surviving an operation were much higher.”

Surgeons began washing their hands once it was realised there was a connection between dirt and disease, which made operations much safer.

The hospital began as a clinic started by two doctors, William Smith and John Singleton, in a six-bedroom two-storey terrace house in Stephen St, now Exhibition St, in the city.

“After about three years there, they moved to a much bigger terrace house in Spring St, where they stayed for another four years before moving to what the older ones among us remember as the old Children’s Hospital in Carlton, corner of Rathdowne and Pelham St,” Dr Yule says.

“And that was a much, much bigger hospital.”

Originally called the Free Hospital for Sick Children, it was initially only for families who couldn’t afford to pay for a private hospital.

Rich children, on the other hand, had to go to private hospitals, which were primarily for adults, with little specialised expertise in treating children.

“As the Children’s Hospital got bigger and better, the ironic thing was that the children who were being treated there probably got much better treatment than the rich children in the private hospitals,” Dr Yule says.

“So for about 40 or 50 years, poor children got better treatment than rich children in Melbourne, which is really weird.”

Dr Yule says while children were in wards of up to 40 beds in the early days, the patients were encouraged to have fun.

“One of the prerequisites for the nurses was that they be able to entertain the children,” he says.

Dr Yule says the hospital believed strongly in the value of fresh air in aiding recovery.

“So quite early on the Children’s Hospital bought a cottage down by the sea at Brighton, and they’d send children down there for two, three, four weeks to enjoy the bracing sea air and help their recovery,” he says.

“And then later on, they got another cottage up in the Dandenongs at Sherbrooke Forest, and the kids used to just love going up there before they were sent home.”

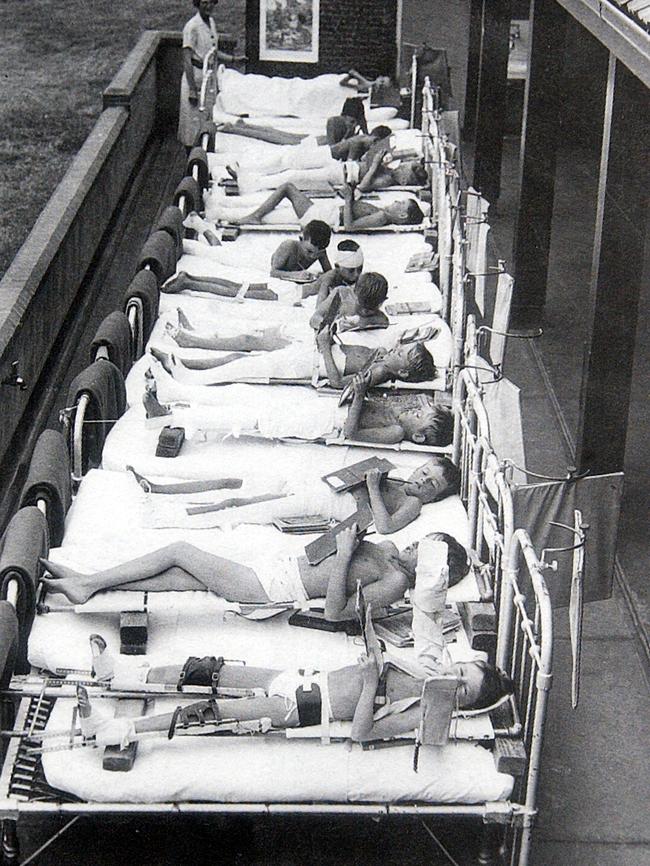

Likewise, kids on the ward at the main hospital often lay outside.

“They’d have the big balconies in the hospital, and if you drive down Rathdowne St and look up at the big red building, corner of Pelham St, you can still see these big balconies,” Dr Yule says.

“They would just be lined with beds and a lot of children would sleep out there, even in the middle of winter.

“There was one girl I spoke to who was there in the 1930s. She was in with osteomyelitis. She was in hospital for years and years.

“And her father used to come and stand down in the Exhibition Gardens and wave up at her because in those days visiting was very, very limited, you know, one, two hours once a fortnight, that sort of thing.

“And her father used to come and wave to her, which I thought was just lovely.”

Dr Yule says the belief was that visitors, even family, would upset the children.

One of the treatments the hospital embraced was heliotherapy, the belief that sunshine could cure kids of crippling diseases, particularly tuberculosis and polio.

“And the women on the committee were horrified to find all these children lying literally naked all round the gardens of the hospital out in the sunshine having heliotherapy,” Dr Yule says.

“They couldn’t believe this was on doctor’s orders.”

Eventually, the committee agreed and set up a special hospital in 1930 at Mt Eliza, which became known as the orthopaedic section.

It was devoted to heliotherapy, with enormous sundecks where hundreds of patients could lie in the sun, and became one of the hospital’s most important campuses.

If you were a child in the first half of the 20th century, telling your parents you had a sore throat was a hazardous proposition.

“Tonsillectomies were, firstly, done as outpatient procedures and, secondly, done to vast numbers of children,” Dr Yule says.

“Anyone who had a sore throat or an earache; they’d pull their tonsils out.

“And they had this day called Bloody Wednesday, so every Wednesday Dr Wilfrid Kent Hughes would come in and do dozens and dozens of tonsillectomies, just with sort of rudimentary anaesthetic, and the kid would be sent home straightaway.”

In his research, Dr Yule spoke to one man who had his tonsils out at the hospital as a child.

“He got the tram into the hospital, had his tonsils out and then got the tram and went home again, coughing blood everywhere,” he says.

In 1953, the Children’s Hospital received royal assent to change it’s name to the Royal Children’s Hospital.

It wasn’t until anaesthetics became more sophisticated that the old technique of a resident holding a chloroform cloth over a child’s face was stopped.

“I vaguely remember when I had my tonsils out, which would have been 1958 or ‘59, that it was still done with chloroform,” Dr Yule says.

“It was pure luck whether you had enough to knock you out, but not enough to kill you.”

The history of the RCH is closely intertwined with the history of the Good Friday Appeal.

The appeal began as a charity sports carnival in 1931 to raise money for sick kids, organised by journalists at The Sporting Globe newspaper, owned by The Herald & Weekly Times.

Some 20,000 spectators enjoyed the carnival after a spectacular Cobb & Co carriage procession through Melbourne’s streets.

Festivities kicked off with a football match featuring competing jockeys from Flemington and Caulfield, followed by a match played by World War I veterans.

The event raised £427, equivalent to well over $40,000 today.

HWT’s managing director, Keith Murdoch, was an enthusiastic backer from the outset.

By then, his wife, Dame Elisabeth, was already heavily involved with the Children’s Hospital, which became one of the great passions of her life.

The couple’s granddaughter Penny Fowler, who is the chairman of both HWT and the Good Friday Appeal, says her grandmother first became involved in the RCH when she was a high school student at Woodend.

“There was a competition of who could knit the most singlets, and so she knitted the most singlets and her reward was to go on a tour of the hospital,” Mrs Fowler says.

“That was her introduction to the hospital.”

Dame Elisabeth then joined the hospital committee when she was only 24 in 1933.

“And then she became the president of the committee in 1954 to 1965,” Mrs Fowler says.

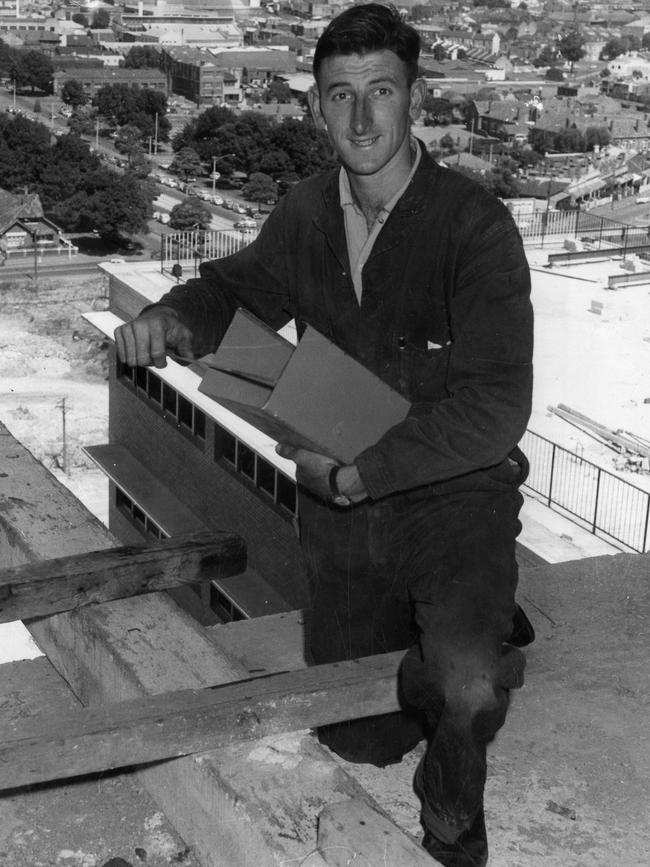

During that time, the then-new hospital in Parkville was opened by Queen Elizabeth II.

“Then she was chairman of the board of the Research Foundation from 1960 to 1968, and then vice-chairman from 1968 to 1979, and she was also patron of the auxiliaries,” Mrs Fowler says.

“So 85 of her 103 years she was involved with the hospital, and she just loved it.

“She didn’t like children being sick.”

In the early years of the appeal, the fundraiser was not held on Good Friday.

That changed in 1942 when journalist and carnival organiser Jim Blake approached Sir Keith to suggest running the appeal on HWT’s radio station, 3DB.

Sir Keith replied, “If you need 3DB, it’s yours for the day.”

This led to the first all-day broadcast of the appeal on Good Friday, and raised £8310 for the Children’s Hospital, equivalent to well over $700,000 today.

In another historic milestone in 1946, the first collection tin appeared on the counter of a Victorian business, at the George Hotel in South Melbourne.

Another grand tradition began in 1953 when the premiership posters, originally created by cartoonist William Ellis Green (aka WEG) and now drawn by Mark Knight, were first sold.

And the first all-day telethon was broadcast in 1957 on HWT’s television station, HSV7, which stood for Herald Sun Victoria or Vision.

Other milestone additions in recent decades have included the Run for the Kids, the Kids Day Out and charity house auctions.

To find out more, listen to the interviews with Dr Yule and Mrs Fowler in the free In Black and White podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or web.

See In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper every Friday for more stories and photos from Victoria’s past.

To donate to the Good Friday Appeal: www.goodfridayappeal.com.au