How Chris Farrington and a team of Australian doctors slowed the growth of vicious cancer

Chris Farrington has stared death in the face, planning a video to be played at his funeral and saying goodbye to his children thrice in a fortnight. But with the help of defiant doctors, he’s been given the gift of time that has allowed him to capture more magical memories with his loved ones.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

As he lay in the medical scanner, Chris Farrington rehearsed the words for a video to be played at his funeral, knowing he would be dead within days.

Over 90 minutes, the machine took pictures of incurable tumours throughout his heavily bruised body, before the 38-year-old was free to go to the rooftop of Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre to spend time with his wife Kath.

They were soon disturbed by one of the dozens of specialists trying to make sense of his extraordinary case, demanding he come to an urgent meeting in his room.

There were five doctors in the room. They told him the medication was working.

“They said that I might see November, I might see December, I might see Christmas … then I just lost it, I was shaking with my head in my hands.

“Two hours ago I was laying in a PET scan planning my funeral and wanting to get this video done to now being told, ‘You can potentially go home tomorrow.’”

A month earlier, Chris had taken sons Miles, 9, and Tom, 6, camping and thought he was in peak fitness starting a new basketball season.

But as he struggled to keep pace with mates on the court on October 3, he wondered if something was wrong. When he saw blood in his urine after the game he knew it.

During a late night trip to Williamstown Hospital’s emergency department a CT scan was taken and Chris was told to come back the next day.

“As soon as I got to Williamstown they said, ‘We have looked at the scans. We think you have cancer on your liver, lungs and pelvis,’” he said.

A friend who happened to be a senior doctor told Chris to get to the Royal Melbourne Hospital immediately.

That afternoon, RMH respiratory specialist Associate Professor Abe Rubinfeld took control of initial tests, but Chris was sent home to wait for more tests a week later.

A barrister with a major trial about to start, Chris went to court to inform a judge he was “very unwell” and have the case postponed.

When he returned to the RMH on October 11, doctors were so alarmed by the results of a positron emission tomography — or PET — scan taken a day earlier they cancelled any further tests.

Mystery tumours riddled Chris’s body.

Worse, the scans showed bruising and internal bleeding everywhere — any medical procedure would cause massive haemorrhaging and risked killing Chris.

Bruising began to show on Chris’s back and all over his legs, so he was admitted to hospital and received the first of more than 330 blood transfusions and blood products.

On Sunday, October 13, everything spiralled out of control and the best medical minds realised Chris had only a matter of days, or even hours, left.

Whatever the disease was, it had triggered a condition called Desseminated Intravascular Coagulation — or DIC — an inflammatory reaction sucking up all the platelets and coagulation factors in Chris’s blood, causing internal bleeding.

Aware Chris probably only had hours to live, Miles and Tom were rushed to the hospital for a hurried goodbye as he was moved to the Intensive Care Unit.

“It was horrible. The fear in Tom’s eyes is seared into my mind,” Chris said. “I sat down on the bed and then they just started plugging all this stuff on to me. I was a bit surprised at what was going on.”

As Chris lay in intensive care, a keen-eyed pathologist noticed a tiny lump on his neck appearing in scans that was not near any major bleed.

A sample of the lump could have been enough to work out what the tumours were — but the procedure to remove it was so dangerous that Chris was given the option of foregoing it to instead spend his remaining hours with his kids.

“I was freaking out. I had a real fear of dying, but my greatest fear was that this was the last time the kids would see me. I could see some appeal for spending 24 hours with them.

“The kids were there and I said goodbye to them again.

“That is the one that haunts me, I genuinely believed it was the last time I was saying goodbye to them.”

With Chris too petrified to make a decision, Kath stepped in.

A sample was expected to show one of three things: lymphoma, which might be treatable; melanoma, which would offer a slight hope; or cholangiocarcinoma, a bile duct cancer that has no treatment and is effectively a death sentence.

Using a large needle, and with Chris awake, a radiologist pulled a sample before anatomical pathologist Dr Anand Murugasu placed it on a slide, looked at it under a microscope and thought “uuurrrggghhh”.

“What I saw was exactly what I did not want to see,” Dr Murugasu said.

“As soon as we stuck the needle in and looked at the needle and saw, I thought, ‘This is not lymphoma, it is really unlikely to be melanoma and they’ve said there is nothing in the lung — we are going to have to get the palliative care team.’”

When intensivist Dr Simon Iles came to work on Monday morning he held on to hope that pathology could still find his patient had a cancer that could be treated, until the results were confirmed late that afternoon.

“All our shoulders dropped because we thought, ‘This is not likely curable,’” Dr Iles said.

Told it was cholangiocarcinoma, Chris and Kath knew he had at best months to live, though with DIC it was most likely days.

“I said to Kath repeatedly I didn’t want to be that person who came into hospital and never left. By that stage it was pretty obvious to me that is what was going to happen.”

Although there was no chance of it saving his life, the collaboration with Peter Mac began chemotherapy in the hope of slowing the bleeding to buy some time.

But unknown to the couple, heartbroken to see a young father with his family but little hope, Dr Murugasu and his team decided they needed to keep trying. The pathologists continued to rush tests on the sample trying to find genetic mutations that more common in other types of cancer.

“I just did some markers to say, ‘Could this be metastatic lung cancer?’ And it had the molecular genetic profile of a lung cancer,” Dr Murugasu said. “I thought, ‘This is really weird.’”

Blood samples sent to the US also confirmed the tumours were cholangiocarcinoma but, somehow, Chris’s tumours carried the same mutation found in some lung cancers.

Remarkably, that exact mutation — found on the ALK gene — is targeted by new-generation lung cancer drug Alectinib.

While he may not have had lung cancer, there was a chance the same drug might be useful for his cancer.

“I rang the oncologist and said, ‘Are you sure this is not lung cancer? Because, if he has lung cancer we can get him this drug that he may respond to.’”

When a group of oncologists walked into the ICU on Wednesday morning, Kath was stunned to see them “bubbling with excitement”.

“They said, ‘We have found a target.’”

Although the odds of finding a treatment that Chris’s cancer would respond to were described as less than one in a million, they had found a drug that at least offered some hope.

Overwhelmed just by the fact specialists had continued to search for an answer, Chris, Kath and their friends went to the RMH rooftop to celebrate.

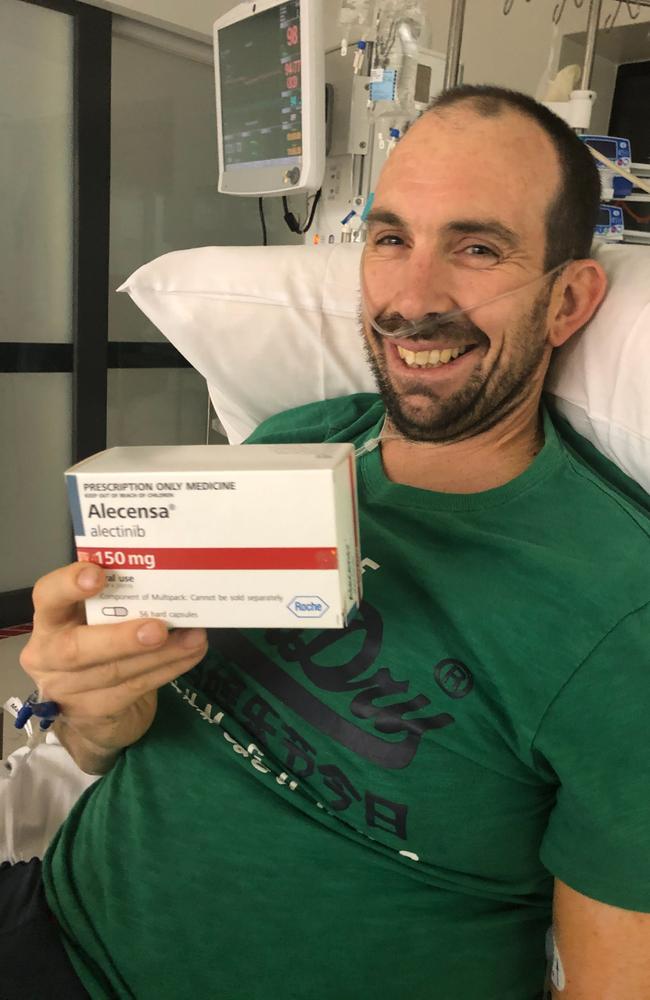

At 9.24pm, Chris was handed a box of Alectinib and posed with it proudly.

More good news followed over the following 72 hours.

“I was very conscious of experimental therapy, how much hope you give him. But it was nice to be involved in a discussion where he got a little bit of positive news,” Dr Iles said.

“He burst into tears and I think a lot of us felt the same.

“We thought he was going to leave ICU for palliative care when we first met him so, for him to leave with the hope of a therapy …”

A week after being admitted to RMH, Chris was moved across Grattan St to the Peter Mac and into the care of Professor Ben Solomon and colleagues.

When the ALK gene mutation was discovered in lung cancers in 2007, Prof Solomon had been involved in trials of drugs to block it.

He had seen ALK work as a switch, telling the cancer to grow and, if you used a drug to block it, the signal turned off and the lung cancer shrank.

Alectinib has since been approved and funded for lung cancer, though there was little evidence to back its use for another disease such as Chris’s cholangiocarcinoma.

But, with the genes responsible for a cancer emerging as potentially more important than the organ or area of the body it starts in, Peter Mac was convinced to pay for the one in a million chance.

“His life expectancy would have been measured in days at that point,” Prof Solomon said.

“But, once we started the Alectinib his condition stabilised, he needed less and less in the way of blood products.”

Another week passed and Chris underwent another PET scan to see if the experimental treatment had had any impact on his cholangiocarcinoma.

It was October 24, but it was still believed Chris would struggle to see November.

As results from the scan emerged they were checked and then double checked by several oncologists to make sure they were of the correct patient, before Chris was summoned.

“The PET scan showed an amazing response — the tumour that had been on was turned off,” Prof Solomon said.

“Saying the response was spectacular would be an understatement.”

Areas that had been completely taken over by tumours in Chris’s first scans now showed no signs of active tumours — meaning they were likely to shrink.

MORE NEWS:

EX-AFL CLUB PRESIDENT’S PUSH FOR DRUG LEGISLATION

WATCH: POWERFUL TV ADS AIMED AT STOPPING DROWNINGS

THE RIPPLE EFFECT: FRONTLINE LIFE AND DEATH MDMA FIGHT

Tumours can evolve to become immune to drugs, so Chris’s medium and long-term future remained unknown.

In some lung cancer patients, Alectinib has overcome cancer for months, but others are still alive five and 10 years after treatment.

The drug’s manufacturer, Roche, also agreed to provide the treatment for free.

“To have come out of a scan and not have it be imminent death was startling,” Chris said.

“I wanted to get to another kids’ sporting commitment — at that moment it became feasible that I might get out of hospital.”

In the middle of his under-10s basketball game in Altona the following afternoon Tom was shocked to see his biggest fan shuffle into the stadium, sit down beside the court and cheer him.

When the game was done Chris, Kath and Tom drove down the road, parked beside an oval and watched an equally surprised Miles play cricket.

Despite having said goodbye to his sons three times in the past fortnight, Chris was again courtside watching Miles’ basketball the next morning, celebrating an uncertain but hopeful future.

“When I was in hospital I thought I would never get to see them play footy or cricket or basketball again. So, to get there and do those things, that was just magical.

“I have discovered, quite confrontingly, how much people care about me. I’ve got to now be in a position where I get to prioritise kids over everything else and I also have an attitude where every day is a bonus. It is a pretty good way to live.”

To help the Royal Melbourne Hospital treat others like Chris Farrington, make a donation to: thermh.org.au/chris