How Brett Whiteley ‘originals’ brought down Peter Gant and Mohamed Aman Siddique

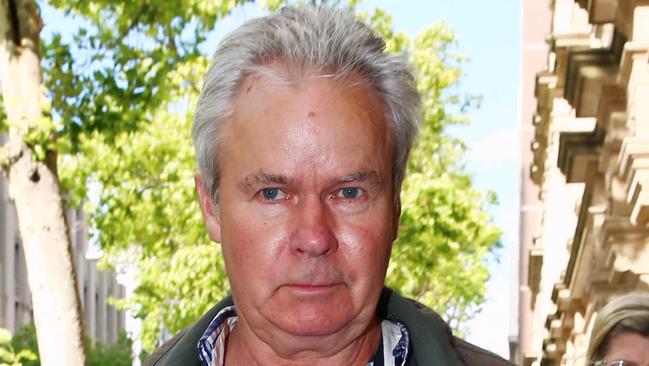

BEFORE Peter Gant was caught flogging dodgy paintings, he would often talk about his supposed lifelong love of art.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

BEFORE Peter Gant was caught flogging dodgy paintings, he would often talk about his supposed lifelong love of art. He once claimed “hairs on the back of my neck stood up” when he saw his first masterpiece.

This confession surprised Gant’s former schoolmates. His supposed love of art must have been well hidden because they can’t remember the dentist’s son showing any interest in drawing, let alone fine art.

They do remember he loved “the punt”, a weakness that showed up early in his time at The Geelong College, where he was a handy 400-metre runner and had photographs of racehorses Imagele and Grand Cidium pasted on his folder.

Young Gant and another budding gambler ran a book on the 1972 Caulfield Cup. They had quoted the eventual winner well under market odds but that didn’t help when Sobar landed a big bet for a wealthy student from Brunei.

“We had difficulty paying,” recalls Gant’s classmate, who admits they then recruited a “heavy” (a big Nauruan student) to handle the winning punter.

It was a close shave but Gant didn’t learn his lesson. More than 40 years later, he is still a victim of the gambling bug, punting heavily and haunting casinos, habits that have led to disgrace. His life has unravelled and his alleged crimes have been exposed in a fraud case that has appalled and enthralled the art world — but not surprised it.

Melbourne writer Gabriella Coslovich is writing a book on the scandal, Masterstroke. It promises something most people love: the inside story of a rort. All the better, in this case, because it’s a variation on the story of robbing the rich.

But instead of wasting money on the poor, Peter Stanley Gant punts it. Robin Hood with a TAB account.

MOST crime mysteries involve a disappearance but art frauds are different. It’s the mysterious appearance of a pair of supposed Brett Whiteley paintings that led to Gant’s downfall, along with co-conspirator Mohamed Aman Siddique.

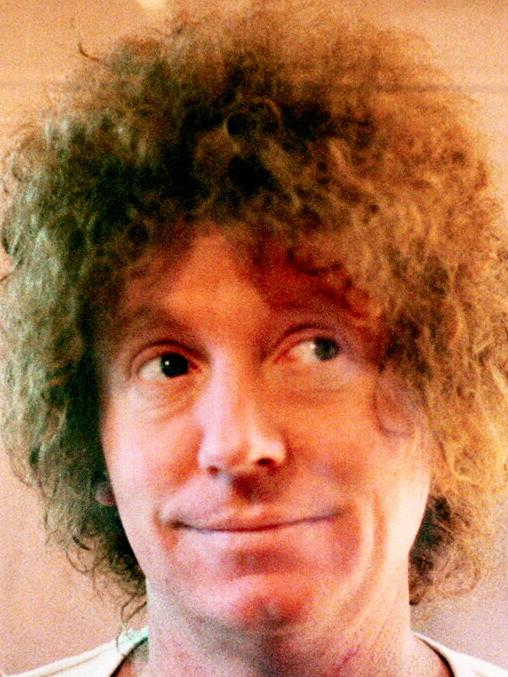

A judge last month sentenced Gant to five years with a minimum of half that. Siddique, 67, got three years with a 10-month minimum after both were found guilty of creating and selling two fake Brett Whiteley paintings for $3.6 million and offering to sell a third fake for $950,000.

The pair had exploited what a critic called the “voyeurism and toxic snobbery” of the art world, according to the judge who sentenced them. The judge then put the sentences on hold pending an appeal.

If you believe the prosecution — as a jury has — Siddique is Gant’s talented sidekick in skulduggery, making them the Dodgy Brothers of the Australian fine art market: a field that, like horse racing, attracts its share of “mug money” and opportunists who prey on it.

Siddique is an expert conservator. Leading galleries hire him to preserve priceless works. He knows painting techniques and has the skills to create what art people tend to call “homage” works, painted “after the style of” acknowledged masters.

The genteel language obscures the cutthroat nature of the art market: it runs on confidence, a commodity as perishable as a hothouse orchid. What art marketeers don’t like are the F-words — “fake”, “forgery” and “forger” — because these are not good for business. Insiders prefer to say a painting is “not right” before discreetly sidelining it.

Perhaps that’s why Gant and other sharp operators have survived so long in a business that needs regular transfusions of new money. There were whispers about Gant for years but no one wants to kill the golden goose over one bad egg.

Gant had weathered earlier scandals before the sky fell in over the provenance of two supposed Whiteley paintings that led to his conviction.

The court heard Siddique created the paintings in his Collingwood studio in 2007, 15 years after Whiteley’s death. If true, this means two witnesses who swore they saw the disputed works in Gant’s possession in the 1980s were wrong.

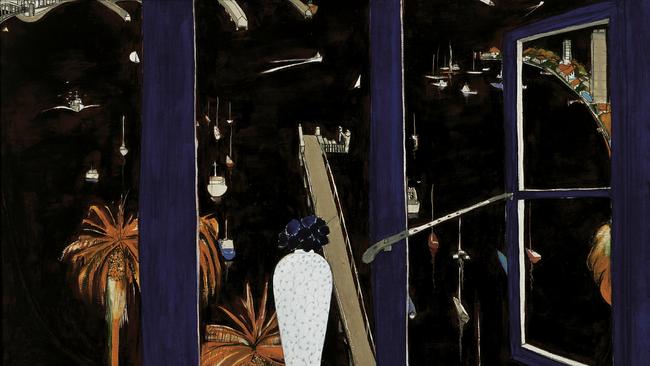

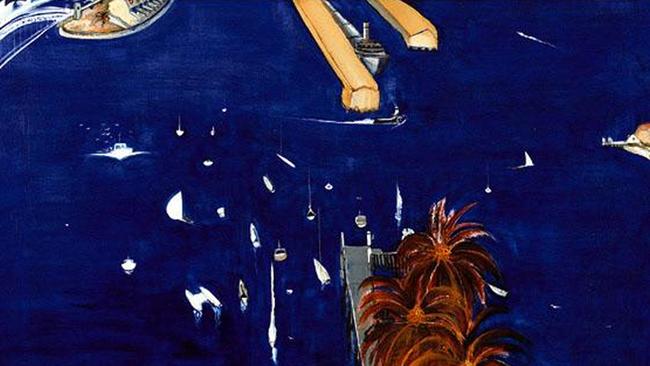

The two paintings at the heart of the case sat in the Supreme Court during the trial. The big blue one is called Big Blue Lavender Bay. The smaller, orange one is Orange Lavender Bay. Both closely resemble a genuine Whiteley canvas — View From the Sitting Room, Lavender Bay — that Gant bought for $1.65 million in early 2007.

The prosecution case is that Siddique painted two fakes, using art books and the genuine Lavender Bay Gant delivered to Siddique after buying it. Gant then organised to sell the orange and blue “Lavenders” as genuine Whiteleys to buyers with more cash than caution.

IN the racing circles Gant knows well, big punters setting up betting plunges use “bowlers” to bet for them. Perhaps Gant used the same trick, as it seems a handful of respected art figures were middlemen in the sales.

Those people were not charged and enjoy the benefit of any doubt. They were no doubt misled with a mashup of lies, half-truths and omissions designed to fabricate a plausible backstory for the two “Whiteleys”.

The tangled provenance would explain why Sydney Swans chairman, investment banker Andrew Pridham, didn’t realise Gant had anything to do with Big Blue Lavender Bay when he paid $2.5 million for it in late 2007.

Pridham bought the painting sight unseen on the recommendation of art dealer Anita Archer, then an auctioneer for Deutscher + Hackett.

Archer said it was a “trophy painting”, writing to Pridham: “From a market perspective it doesn’t get much better than this.” What she didn’t tell him, if she knew, was that it came from Peter Gant. Instead, she referred to it being owned by one Robert Le Tet. Gant had assured Archer Le Tet had commissioned the painting from Whiteley. But this was different from what Gant told police in 2014: he had bought three paintings from Whiteley’s studio manager, Christian Quintas, in 1988 and had kept them until 2007.

Pridham was happy with his purchase until Whiteley’s widow, Wendy, came to his house to inspect the painting. Although she did not actually denounce the work, she was so sceptical Pridham later sent it to University of Melbourne art expert Robyn Sloggett.

He had a name for uncovering wrongly attributed pictures, which is what she branded the big blue painting. Her opinion supported Wendy Whiteley’s and was persuasive enough that Pridham sued Archer — extracting a confidential payment on the trial’s eve. The orange painting had taken longer to sell. First, notable art collector Kerry Stokes declined to pay the asking price of $1.3 million, then Aussie Home Loans founder John Symond passed at $1.5 million. It took until 2009 for the painting finally to be sold for $1.1 million to a car dealer, Steve Nasteski. But the art dealer who did the deal for Nasteski smelt a scam when he actually saw the picture. Nasteski hounded Gant’s intermediary, dealer John Playfoot, until he got his money back. Apparently Gant lost confidence in his orange masterpiece, as he sold it to a Toorak engineer for just $122,000 in 2013.

The testimony of art sleuth Sloggett, combined with an angry Wendy Whiteley, was enough to sway the jury to ignore two witnesses Justice Michael Croucher reckoned had derailed the Crown case.

Rosemary Milburn, Gant’s former gallery assistant, told the court she recognised a consignment note recording the arrival of the disputed paintings at Gant’s gallery in 1988. A Jeremy James testified he had photographed Big Blue and Orange Lavender Bay in 1989 for a Gant catalogue.

Justice Croucher said Milburn’s and James’s evidence torpedoed the prosecution case. He offered the jury the chance to acquit immediately. But the jury, apparently fascinated, declined the offer, sat through the defence case and closing arguments then returned a verdict that will put the accused behind bars — unless appeals overturn the convictions.

————————————————————————————————————————

RACING people trust Gant more than art people do. Garry Murphy, the veteran jockey who rode the Gant family’s horse, Just The Part, to win the 2004 Ballarat Cup, recalled a part-owner with “a great sense of humour” and a gentleman when betting went wrong.

In the mid-1990s, Murphy rode a horse at Warrnambool for the Gants — Peter and his late parents, Austin and Hazel, among other owners — and got beaten. It was a bad ride and cost Gant a fortune.

Gant was “distraught” after the race. But next day it was as if it hadn’t happened. Not that he forgot. When Murphy won on Just The Part a decade later, Gant chortled: “That gets back what I lost at Warrnambool!”

Gant took out an owner-trainer licence and briefly trained a couple of horses near Geelong. Murphy said he loved horses and treated them well, though he knew little about them. But his kindness to dumb animals apparently did not extend to dumb art buyers. A prominent auction house identity said it took decades to develop “the eye” to pick suspect paintings. About 20 years ago, he said, he noticed often when he rejected a picture and traced its provenance, it led to Peter Gant.

In art circles, the Whiteley scandal is the nail in Gant’s coffin as a dealer, even if he wins an appeal. What the jury was not allowed see during the trial were photographs of other works-in-progress spotted in Siddique’s studio — including obvious copies of other famous artists.

There is no law against copying pictures. Only against passing them off as originals — a gamble some just can’t resist.