How bold 1969 freeway plan could have reshaped Melbourne

A freeway grid and new rail lines were part of a bold 1969 Melbourne transport plan that’s still shaping our city today. What worked, what didn’t and what should have been built?

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

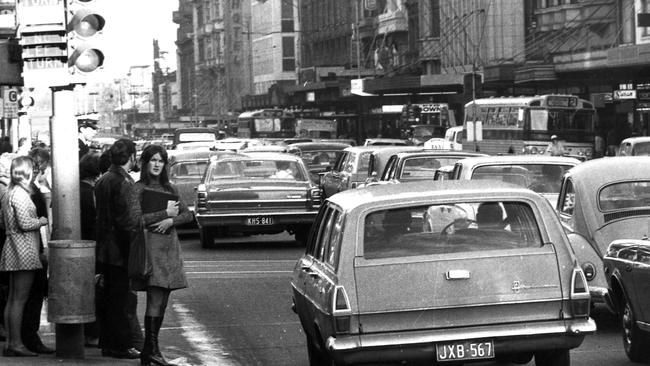

The 1969 Melbourne Transportation Plan was released 50 years ago, but its effects are still being felt today.

If it wasn’t for the plan, we would not be arguing over the East West Link and the North East Link. We would not have the Ring Road or the M1.

And hopes for railway lines to Doncaster and Rowville that commuters still demanded today would never have been raised.

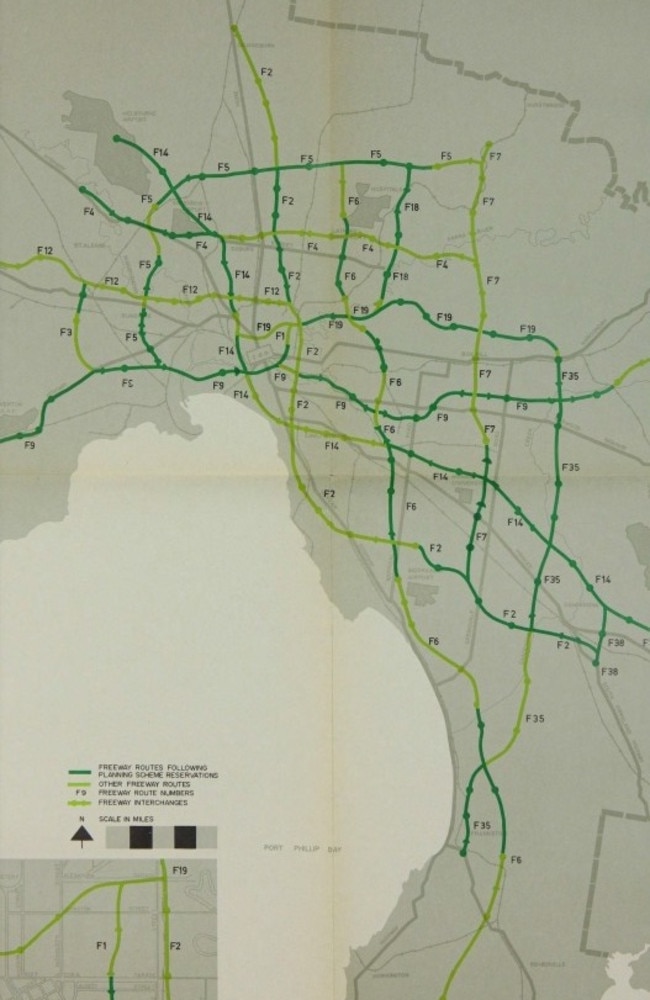

It was billed as a comprehensive transport strategy that combined road, rail, tram and bus improvements but was mostly a freeway blueprint.

Looking back from 50 years on, senior lecturer in transport planning at the University of Melbourne, Dr John Stone, says the plan was a flawed document.

It was aimed to cater for Melbourne’s traffic needs well into the future – all the way to 1985, when it was estimated Melbourne’s population would be 3.7 million.

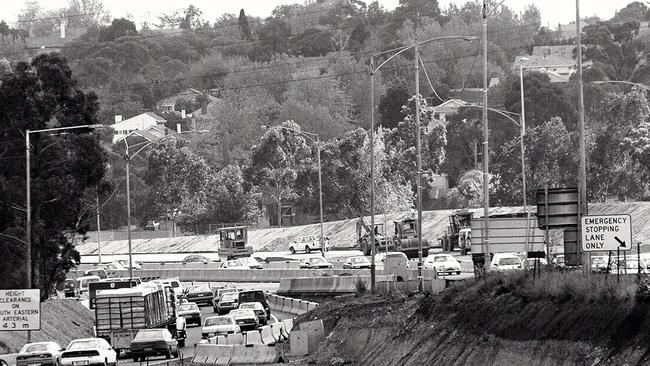

The old South Eastern Freeway existed in late 1969, when the plan was released.

The Tullamarine and West Gate freeways were under construction, and roads such as the Eastern Freeway were planned, but that was the extent of the freeway system.

Roads including the Mulgrave Freeway (later linked to the South Eastern and called the Monash Freeway), a variation of today’s CityLink, the Eastern Freeway, the ring road, EastLink, the Frankston and Mornington Peninsula freeways and the Hume Freeway north of the ring road sprang from the plan.

It also set in stone the City Loop underground rail system. Work on this began in 1971. Its first station, Parliament, opened in 1981 and Flagstaff, the final station, opened in 1985.

But there are major gaps today. The plan proposed a slew freeways and arterial roads that ringed the CBD and crisscrossed inner, middle and outer suburbs.

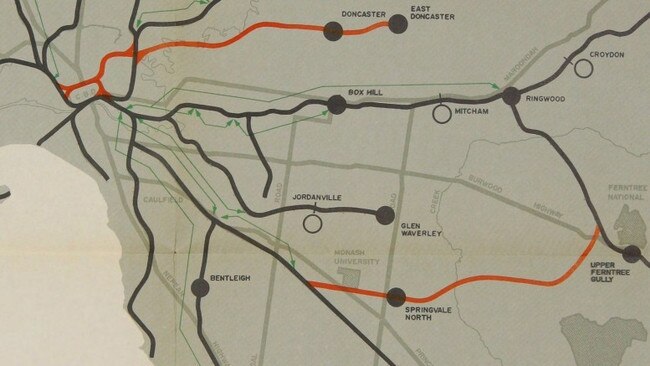

THE PROPOSED TRAIN NETWORK

The plan also proposed major rail network improvements including new dual track electrified lines:

•from Victoria Park to East Doncaster with new stations at Balwyn North, Bulleen, Doncaster and “Koonarra”, between Doncaster and East Doncaster

•from Victoria Park to the City Loop with a new station at Fitzroy

•from Huntingdale to Ferntree Gully with new stations at Monash University, Springvale North, Mulgrave, Rowville and Knox (which would have serviced VFL Park), and

•from Frankston to Dandenong with stations at Wells Rd, Karingal, Carrum Downs, “Harwood”, linking with Lyndhurst on the Cranbourne line.

Proposed electrification was completed to Werribee, Sunbury and Craigieburn – the latter two only in this century – and many track section duplications and signal improvements are done.

But plans to extend metro electrified rail to Coldstream, Mornington and Hastings have been abandoned, while proposed electrification to Deer Park West is now underway all the way to Melton.

These would have seen freeways and major arterial roads ploughed through now prized heritage buildings and neighbourhoods.

The F18 took today’s Eastern Freeway route to Hoddle St, before swinging southwest through Collingwood, Fitzroy and Carlton and connecting with the Tullamarine Freeway in North Melbourne, with interchanges in the heart of Lygon St and the Haymarket roundabout in Elizabeth St, among others.

The road we now call the Hume Freeway was part of the F2 in the plan.

The F2 would have run along the Merri Creek through Reservoir, Preston and Northcote, linking with the Eastern Freeway at Abbotsford, running parallel with Hoddle St and Punt Rd through Abbotsford, Richmond, South Yarra and Prahran, then dividing St Kilda, Elwood, Brighton and Moorabbin before winding southeast to join today’s South Gippsland Freeway.

In fact, two freeways would have intersected at St Kilda – the F2, and the F14 (connecting Tullamarine Freeway from the airport through West Melbourne and just west of Spencer St Station, through South Melbourne and Albert Park and east through to today’s Monash Freeway through the inner southeast).

East West Link as we know it was not on the cards, but several east-west freeways would have connected the Tullamarine, Eastern and West Gate freeways.

The F1, for example, sliced through Jolimont, East Melbourne and Collingwood to connect to the F18 Eastern Freeway.

The North East Link has been on the books for 50 years. It shows as F18 on the plan, and like all the others was proposed as a freeway at ground level.

The scale of the freeway plan was immense, and worth almost $1.7 billion alone in 1969 (that’s $20.3 billion today).

SO WHY DIDN’T IT ALL HAPPEN?

“Melbourne would have been a totally different place, particularly in the inner suburbs. It would have been a whole lot worse, but in a lot of ways (the plan) has guided transport planning in Melbourne ever since,” Dr Stone said.

“Slowly, governments have built the outer suburban parts of the network, and CityLink, and it creates pressure. If you build one, you’ve got to build the next. It shapes politics.”

The plan was developed by a committee comprising government and public works officials in concert with a US construction firm, Wilbur Smith. Several other US firms were active in transport planning around the world at the time.

“They would put this same template on cities around the world – Helsinki, Vancouver, New York, Melbourne – all the Australian cities – imagining that public transport would die, everybody will have an individual car and we’ll have enough roads for that,” Dr Stone said.

“Really, what they forgot is that underneath those roads were places where people lived. “People in Melbourne fought back really strongly, and inner city parts of the plan got cancelled.”

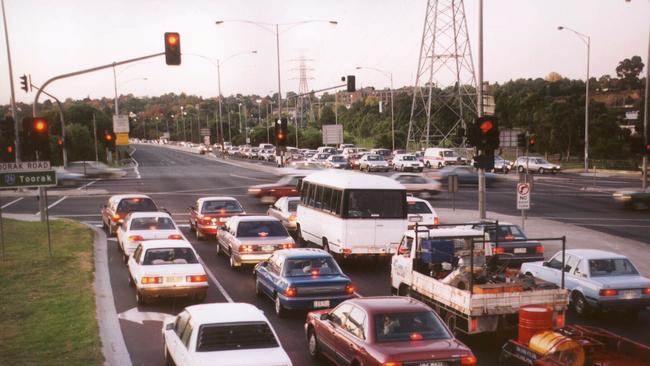

But pressure is still building to link the Eastern, West Gate and Tullamarine freeways through East West Link and West Connect.

Public transport patronage in the 1960s was dwindling faster than almost every other western city except Auckland and it was assumed cars would dominate.

“It was almost a cult, when you look at it now,” Dr Stone said.

“So many more people at the time believed that you could resolve questions of city planning through mathematical formula, and that’s what this plan is the result of – a scientific ideal.

“The plan set up a way of thinking about traffic that if you knew where people wanted to move, you could figure out how big the road would have to be and you could build it.

“What that didn’t take into account was how much building that road generated new traffic, people changing where they live and work. Every time you built it, it filled up. Every time you widen the Monash, you start at the other end and widen it some more.”

The emphasis on roads sidelined rail in the plan, and proposed little change at all for trams and buses.

“What rail people wanted most out of the plan was the City Loop, and we built that. It reshaped the CBD, eased congestion and helped the CBD survive in a time when they thought suburban development would overtake it,” Dr Stone said.

“The tram people were seeing lines getting ripped up around the world, so the fact trams survived was their success.”

While the plan acknowledged the need to unite rail, tram and bus services in a single entity to ensure proper co-ordination between each, it never happened.

“We still don’t integrate planning and we don’t think what the best solutions are for a particular place. Our trains, trams and buses don’t work as a seamless system,” Dr Stone said.

READ MORE:

HIP BURBS THAT USED TO BE SLUMS

NORWOOD: STUNNING MANSION TORN DOWN

Melbourne in the 1960s was made up of ribbons of suburbs along rail lines that gave people a comfortable suburban lifestyle close to trains, but problems arose as wedges between the rail lines filled out in the 1970s and ‘80s.

“The car gave us the freedom to develop spaces in between the railways. We could have said that we would give people a bus service that gets you direct to the railway – that’s what Toronto did, and the plan said that we would do the same, but it never happened,” Dr Stone said.

“If Melbourne had gone through with regular direct bus services into those wedges, people’s lives and their experience with public transport would be better and we could have developed the political support for the railway extensions.”

Read the full final Melbourne Transportation Plan here.

@JDwritesalot