How Australian of the Year Neale Daniher has given us hope through his battle with MND

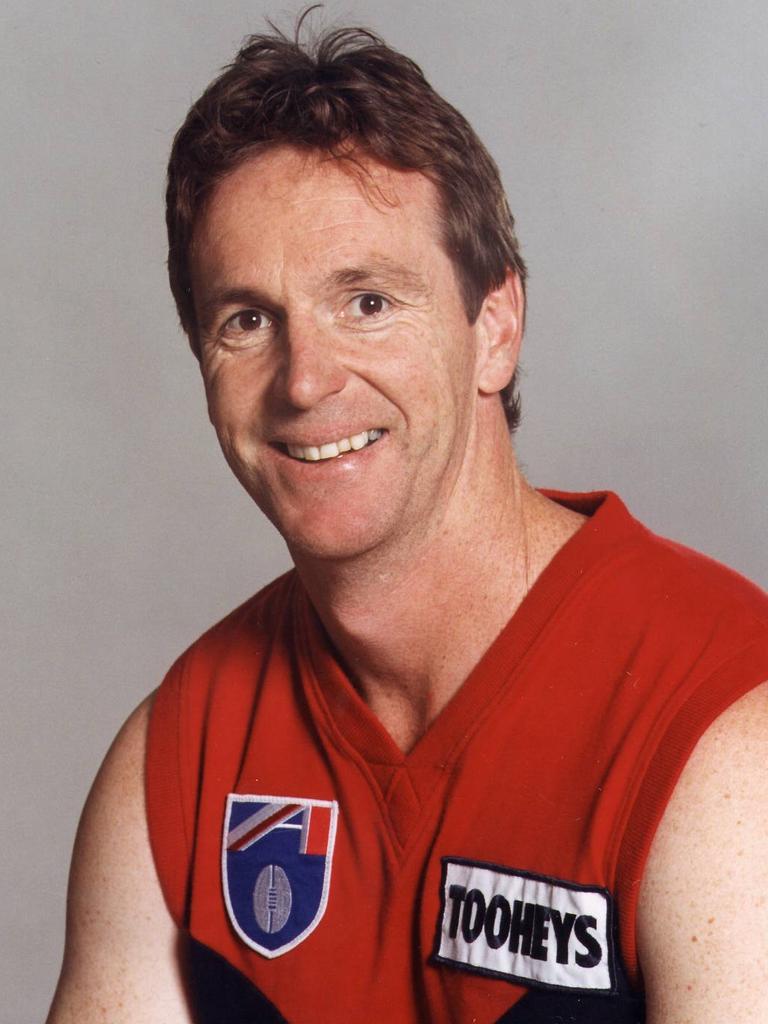

Australian of the Year Neale Daniher is no salesman. A no-nonsense country boy. For him, he ‘wanted to make something’ of his time on Earth.

His fingers went first, so quietly that he would only later link the little moments that hinted of the doom ahead.

He couldn’t peg clothes to the line. He fumbled his keys. When he caught up with old mates for a beer, they thought he’d preloaded. There was a vague slur in his voice, easy to mistake for inebriation.

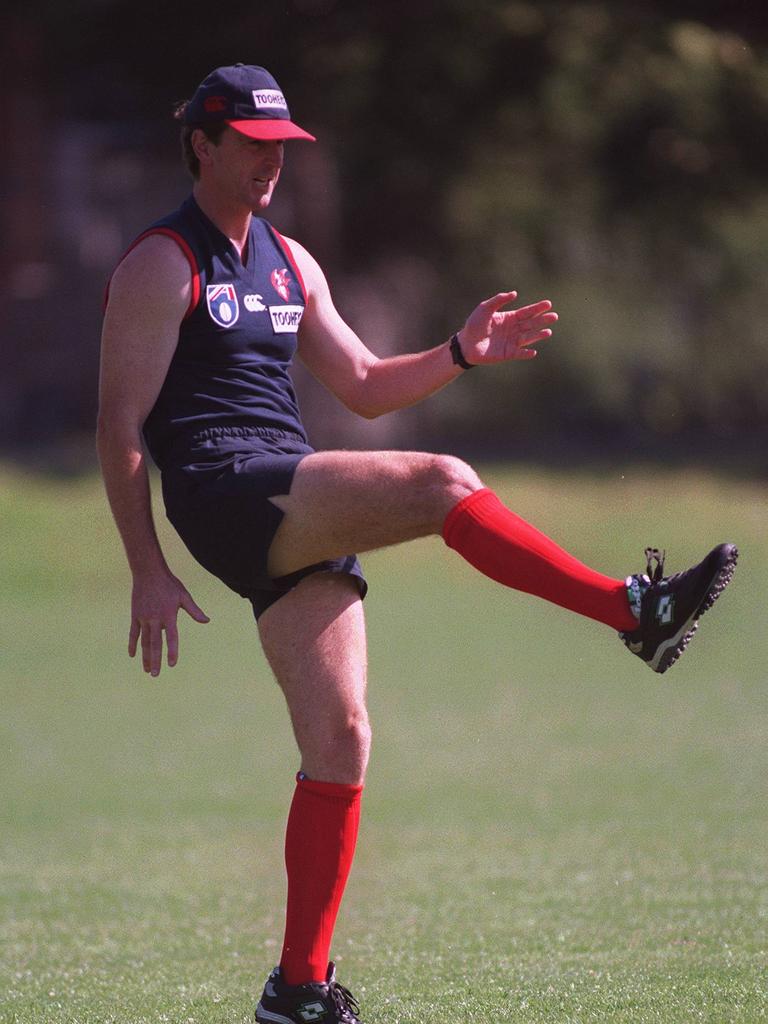

Neale Daniher has always been a doer, impatient of nature, one of 11 kids hardened on the red-baked soil of a farm. He learned early that life handed out few free kicks. After a career in footy’s lucky dip of discards and also-rans, he figured that the only approach to adversity was to slog on until the problem had dimmed.

Yet he couldn’t cast aside this particular problem. No one seemed to know what the problem was.

Doctors hoped for something treatable, such as a spinal tumour or MS. He was fit, at 52, when he was diagnosed by elimination. He had MND.

People like Daniher average 27 more months of life after the bad news is delivered. He didn’t believe it, not until second opinion, when he emerged from the hospital into the Melbourne grey and thought: “Fuck, I’ll be dead in two years.”

He didn’t know much about MND: not many people did. He had been marked for the most incapacitating disease known to humanity. It would get harder. And bleaker. Almost no treatment and definitely no cure.

“No time for crap red wine anymore,” he texted a friend.

The cards had been dealt, to borrow one of his preferred metaphors. It wasn’t the poorness of the cards, but the manner in which you played them which counted, and the MND diagnosis tested everything he had believed.

“I always wanted to make something of my time on this earth,” he once wrote, “to have my hands on the wheel of life, not just be a car crash waiting to happen. The thing about life is that it is short and precious and there’s nothing like a terminal illness to reinforce that.”

In 2017, he got released from a Canberra hospital after being unable to breathe with flu. Told to drive home by a doctor, and not fly, he dutifully drove – to the airport – figuring there was no time for long car rides.

In 2020, he had no way to brace if he fell – his arms obeyed only the laws of gravity.

Walking would start to fail, as would talking. There was some woe-is-me depression after the diagnosis – how could there not be?

Yet Daniher would instead apply mind craft to reality. He called MND “the Beast” – “hairy and dark, like a huge hybrid of a blowfly and a moth” – to personalise his fight against it.

It could take his arms and legs and his ability to sip red wine (though not entirely his grimace when it was bad red wine). Yet the killer has not stolen his attitude, grounded in the reading of many psychology books over the years.

He would “choose one’s own way”, as an Austrian Holocaust survivor, psychologist Viktor Frankl, put it.

Daniher’s spirit is not for pillaging. And so he has tackled the complicated cruelty of motor neurones which no longer fire properly with this seemingly unlikely conclusion: that his fate was not a sentence, but an opportunity.

He has used this word a lot to describe a deadly condition. And an odd thing happened. His mind could not shift the physical decline. But it did up-end the natural order of things.

As Daniher has shrunk of body, he has grown of stature. By the time he lost the ability to speak, his voice had never been louder.

It’s difficult to recall a more worthy Australian of the Year, not because other recipients have lacked merit, but because no other recipient has so moved us with such raw example.

Daniher was once called a “potent cocktail” because he boasted both a public profile and “the bastard of the disease”. As co-founder of FightMND Patrick Cunningham would write, Daniher “could entertain and inspire people like no one else”.

There is nothing not to like here, except the blind randomness of nature. Daniher has neither sugar-coated his fear nor pretended that his death will be fair.

But he has swapped out the conventional ways, such as pity and depression, for joy and optimism.

His life has been stripped of vanity. His message is plain, a nod to old-fashioned qualities that seem so unfashionable in public life today. He has coached us to be better by raising his middle finger to a future which will only get worse.

Self-pity, if there has been any, has been for private. There was always someone suffering more than you, he learned early. He wants us to hope, not so much for him, but for the two or three Australians a day who discover that they share his sentence.

True, he does want something in return. It isn’t sympathy. In life, with the time remaining, he invites us to embrace his legacy.

Daniher is no salesman; the no-nonsense country boy would shy at such patter. For him, you suspect, the advent of “wellness journeys” or the like are strictly for wankers. And yet the manner of his life has come to be wrapped in the business of hope.

There has been Australian understatement, and diversions into black humour, some dance bopping with his little granddaughter and boyish delight at the top of the MCG water slide. And there has been no false bravado, no masks behind masks.

In this story of true grit, this tale which bows to so many of the touchstones that we like to claim as national character, Neale Daniher has taken charge of the untameable by offering us the best version of himself.