Hamish McLachlan: What drives Olympic swimming coach Dean Boxall

Famous for celebrating like no other Olympic coach, Dean Boxall is so competitive he even “targets weakness” in his young son’s tennis game.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Dean Boxall was born in South Africa and moved to Australia when he was seven. He swam at a high level, but retired at 18. He says he “failed” because he didn’t achieve his objectives in the pool. He started coaching, and is now head coach at St Peters Western in Brisbane. He coaches some of the best swimmers in the world.He spends his days obsessing over how he can find ways to make them better. He is demanding, of them, and of himself. And when they win, he wins with them, and celebrates poolside like few have before.

HM: Born in Camps Bay, South Africa. Are you a South African or an Aussie, Dean?

DB:The blood is South African, the mind is Australian. I always look back on South Africa with fond memories, and I follow their sport very, very closely. I love seeing the Springboks win the Rugby World Cup; I just know how tough and resilient that nation must be. My father will hate me saying this, as he is South African, of course, but inside, he believes he’s now a true blue Aussie.

HM: Your father said: “We need to leave South Africa” when you were only six-months-old. What was the rationale?

DB: He believed there was going to be unrest and there wasn’t much of a future there for his family. They packed up and jumped on a boat when I was six-months-old and arrived on the shores of Sydney but it only lasted four weeks as mum struggled. She had two kids, no friends, no support and no family. We got on a plane and went back to South Africa, and it took dad another seven years before he said to my mother: “We’re going back to Australia, this time to Brisbane, and if you don’t follow, then the boys will follow when they turn 18.”

HM: You were seven at the time?

DB: Yes, I was. Dad got on a plane six months earlier to prepare for our arrival and find some work. He started working at Channel 7 in 1984. During his time at Channel 7, he was fortunate enough to go to the Olympics in Barcelona and Sydney, I believe.

HM: What was he doing for Seven?

DB: He was a technical engineer. When I finished school, he organised for me to work casually for Seven too; behind the camera man, controlling the cord and also running the audio down the sideline for the Queensland Reds and Wallabies.

HM: When did you first jump in the pool?

DB: Mum had me swimming when I was three. She was a swim teacher and a solid swimmer. She represented Western Province in South Africa, which is a state team. She is still a Learn To Swim teacher. My father was a professional soccer player, so there was sport in the family, but mum was absolutely in love with swimming, and I happened to fall on that side of the sporting coin.

In my mind I was a failed swimmer

HM: How good a swimmer were you?

DB: I made the Australian Junior team but in my mind, I was a failed swimmer. I never made the senior team and that was my goal. It hurt, but I just loved the sport. After the Tokyo Olympics, someone who I used to train with, Pelham Higgins, who now lives in Japan, said to me: “Dean, when you were 16 you said to me that all you wanted to be after swimming was a swim coach.” I can’t believe I said that.

HM: And you stopped swimming when you were 18?

DB: And then on Monday, October the 13th, 1997, I started coaching.

HM: You’ve said you left your sport “at the bottom” and as a result your self-esteem was shot.

DB: My self-esteem was zero. I left the sport I loved as a loser, I never achieved my goals and I quit after a meet that I swam poorly at. I was mentally fragile and empty and I departed my sport at the lowest point. I now endeavour to not let this happen to my team of swimmers, as difficult as this is. You’ve got to retire on the up or at the top, otherwise you’ll have a harder journey afterwards.

HM: Michael Bohl was one of your mentors growing up. He said you would make a great coach. What do you think he saw?

DB: He saw how much I loved the sport, I had so much passion and enthusiasm for being around people. I loved being around people so much that I was going to go to university and study teaching because I loved being around kids - around teenagers and people, trying to help development and performance. I didn’t end up teaching, which I regret a little bit. I studied human resource management at a university because I just loved performance management, recruitment selection and training development. I loved trying to get the best out of someone, trying to motivate them. However, I eventually did a subject called industrial relations, and that changed everything because I hated it. I have a degree in human resource management and advertising and a diploma in business management. But swimming coaching was always in my blood.

HM: Were you a decent student? You are an unbelievable student of the pool and of the mind, but academically, how were you?

DB: My parents knew how much I loved swimming, and they just said: “Dean, just make sure you pass school.” I’d get home at 7.30pm, and I wouldn’t sit down and study for hours to try and get As, I just did enough to get by. My friends wanted to be doctors or lawyers because their parents were. However, I never had that desire. They are doctors now, they are lawyers – I just had swimming. All I wanted to be was a swimmer and then a coach.

HM: You talk about a lack of application at school. Somebody said to me that the swimmers that you coach switch off but you never do.

DB: I never do. That’s the issue, and it’s an issue for my family. I never thought that I would burn out but a lot of people around me, my mentors, were always saying to me: “Dean, you’re going to burn out. I’ve never seen someone with this much energy, and push, and drive, but you’re not stopping.” I always looked at them and laughed. I’ve had this energy since I was born.

All I wanted to be was a swimmer and then a coach

HM: Is it exhausting for you?

DB: Absolutely exhausting. I remember taking on the job from Michael Bohl when he left in August 2017 and I wanted the club to keep moving forward and not falter. We had the Commonwealth Games trials in February, followed by the Commonwealth Games in April, then the Pan Pacific trials in June, followed by Pan Pacs in August, then straight onto World Short Course trials in October and then the World Short Course championships in China in December. I just kept pushing, and driving, and pushing. Then in 2019 we were coming into that penultimate year of our Olympic campaign and that’s where you’ve really got to be on your game. I was obsessed with trying to get that right. Then it was the Olympic year and then Covid came. It was a huge five years. I had to check my energy. I went to a hospital in October of 2019, into the infectious disease ward, for four days. My white blood cell count was off the charts. It was stress due to the push, the drive, the obsession, trying to get it right. That’s where the burnout started.

HM: You spoke about your obsession, your fanaticism, affecting your marriage and relationship with the kids. How do you try and measure family life with training athletes to become Olympic gold medallists and world record holders?

DB: In 2019, Wayne Bennett came and spoke at the St Peters Lutheran College sports luncheon. I was so happy that Wayne was talking because I’d never had the opportunity to listen to Wayne, and Michael Bohl had always spoken so highly of him. It was one of the great speeches. There were questions at the end, and I normally sit there and just take in the information but I had to ask a question in front of everybody – there were 400 people there. I asked Wayne: “How do you manage the demands of your job and your family life?” He said, “Dean, I’m not good at it, I just know that I have a job to do with my athletes and I have a job to do with my family. When the family need me, I’m with my family, and when my players need me, I’m with my players. That’s all we can do.”

HM: I remember you referring to Arnie (Ariarne Titmus). You said: “I am the author of her pain.” What you do is you get young athletes, and performers, to be more disciplined, and more focused, than most people on the planet. What is the secret to that?

DB: I don’t know the answer because I haven’t had the opportunity to sit back and really reflect on how I do things. If I see talent that’s not just to do with athleticism but the mind too. I’ll do whatever I can to try and extract that maximum performance from them, to make them believe, to build their confidence. What they are doing, especially the school kids, is incredibly challenging and demanding. They get up early, they’re at the pool by 5am, they train, and then they go to school. Then they’ll come to training at the end of the day, where they’ve got to perform, and then they go home to do their homework. And do it over, and over, for the next five days. Then Saturday morning comes around, and that’s one of the hardest sessions of the week. They will have moments where they don’t want to try hard in the pool, and I just try and make sure that they hold themselves accountable.

HM: Are your children unbelievably disciplined and respectful? Or are you like the accountant who never does his books, or the mechanic whose car keeps breaking down. Is it the same at home as it is in the pool?

DB: My wife is from Slovakia and she is tough. She is stoic as. My oldest son, Kaden, who’s eight, is loving tennis. She’s been taking him for tennis lessons and I haven’t gone to watch him yet. I have played a few times with him and I go quite hard when I deem necessary. If I see he has a weakness, I just target that weakness.Let’sjust say he doesn’t like a sliced back hand, I will slice the next 40 shots at him. If he says to me: “I don’t like the slice”, I will continue to slice. He might get upset, and I’ll say: “You have to learn. My job now is to show you that and you have to try and fix it”. I guess it is the same at home as in the pool at times. My wife would check me off though.

I go quite hard . . . 1f I see (my son) has a weakness, I just target that weakness

HM: There must be a balance, when trying to create a confident, bulletproof athlete, between reinforcing the strengths, and focusing on the weaknesses?

DB: There is – absolutely. You’ve also got to know who the athlete is. For example, Arnie is very different to Elijah (Winnington), Elijah is very different to Mollie (O’Callaghan), and you’ve got to make sure you know ‘the right key to each lock’. You have a set of keys, a thousand of them, and one lock. That lock is the athlete. You must find the right key that opens that lock. And once you find it, that is when the magic happens.

HM: How do you balance the messaging? You have Arnie, who has an unbelievable appetite for work, and seemingly, was more mature than most 15-year-olds, and other 15-year olds who are more fragile?

DB: Just by knowing the athlete. Most people can’t take the messaging in the same way that I give it to Arnie. You’ve got to be open with them. If I spoke to an athlete and they said they wanted to win an Olympic gold, I’d have to tell them: “Do you understand what you’ve just said? Because if you’re just saying it, and you haven’t really thought about it, that’s disrespectful to all the Olympians who have tried to achieve gold.” You need to marry what they’re trying to achieve, with the application and effort. If someone comes up to me and says they want to win the state championships, you don’t have to be like Arnie. If someone says ‘I want to be a part of the squad’, or ‘I want to make a national final in the 400m freestyle’, the way you pursue that is far different from someone who wants to win an Olympic gold.

HM: Some people have an eye for a horse or can see an athlete as they jog around a track. Can you see a swimmer within seconds?

DB: You can see a swimmer in seconds but it takes longer to see a champion. If I go to any pool I can sit in the grandstand and identify if a person was an ex-swimmer, or if that person has a great feel for the water but a champion mindset and a person that can handle the pressure, or a person that can turn doubt into an asset, I’d need to spend some time with that person. Someone who is dogged that never gives in, has a great spirit, great attitude, and really wants to work and is a pleaser, someone who hates to lose. There are people who love to win, but the person who hates to lose has a deeper desire than the person who loves winning, in my opinion.

HM: How much is physical, and how much is mental? If Arnie had all the physical attributes that she has, but mentally, wasn’t as tough by 10 per cent, is that enough to miss an Australian team, to miss medals?

DB: Absolutely. Some people go to the Olympics and get caught up in the scene and some people love that environment so much that it’s like a vacation to them, because they thrive under pressure. They love that drive, they love that environment, they love the pressure, they feel it, they absorb it, and get stronger with it. They use it to optimise their ultimate performance. Michael Phelps goes to the Olympics for his vacation because that’s his place. Katie Ledecky, Ariarne Titmus, they love it. That’s their place. The Brisbane Lions of 2001, 2002 and 2003 – the AFL grand final was their vacation. They loved it. That’s where they became their best.

HM: They are almost born to be there.

DB: They use that environment to be their best, to become the best. They love it.

HM: You and I spoke just after the Tokyo Games, and you were convinced that Arnie was winning on the basis that all the work you’d done, and everything you had achieved together in the lead-up, and where her mind was at, there was no one in the world that could beat her.

DB: I did. And she got the world record just last week, and I can tell you, Hamish, she still has a lot more in her.

HM: How do you know that?

DB: I’m the author of her pain but also the author of her program. I’m seeing things that she’s got better at in all facets of her swimming. And one of the most important things is, she’s in a great position in her life. She’s happy and she’s enjoying her swimming. She has this aura about her because she is the double Olympic champion. She hasn’t been put back into that pressurised environment yet, and that’s where she thrives, so she will get better again just from the environment. Comparing her to the last year, and the year before, she’s a better

athlete.

HM: I was worried that after Arnie had reached Everest, that getting back into the water and getting motivated again might have been a problem. She doesn’t seem to have had any problem with that.

DB: And I was concerned as well. You must remember how much went into this, how much was put in, how much energy, investment, time. She’d climbed Everest, the Olympics was done, and it was another three years away. Arnie had a massive break, and I thought ‘how do we climb back up?’ She came back and was in love with swimming. Everything in her life was good, she was in a great position, had a great sense of being, and she’s a girl who has always loved training, loved racing, and loved everything about swimming. That’s the biggest difference between her and other people. If you only love to race, and you don’t love training, you’re going to struggle. But she loves training, she loves racing, just everything about swimming.

HM: You and I just watched Rafa. What is it about the Rafas, the Arnies, and the best in the world, mentally? Is it an inner belief, is it training, a lack of fear, a fear of failure?

DB: It seems like Rafa has doubts but he turns them into a weapon. He turns it into something that motivates him. He doesn’t want to ever let it beat him. He has huge confidence in his ability, and he goes to the French Open and he owns it. He goes to training every day, thinking, ‘I’ve just got to get better, to keep improving’. Those are the best athletes in the world. They apply themselves, they have discipline, they go to bed at the right time, and they eat right. Everything that surrounds their sport, or their game, or their profession, is professional.

The best athletes in the world . . . apply themselves, they have discipline

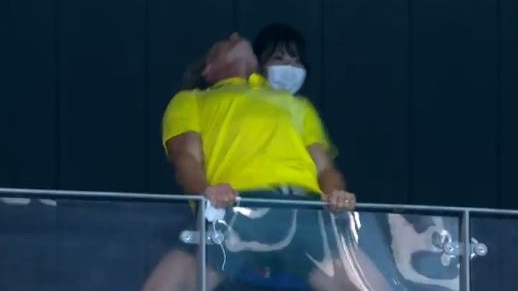

HM: The excitement when Arnie beat Katie was felt by every Australian and you embodied us all with your celebrations. What people didn’t understand was that’s standard fare for you. You are so emotionally invested, you let it all out with your athletes. You are obsessed by them, you spend so many hours working with them, and then when they perform, you’re so emotionally invested it’s an outpouring of emotion.

DB: That was complete relief in Tokyo because I was obsessed with the numbers trying to get this race right. To try and topple Katie, I’d studied her, I’d studied the race, and I knew they knew where Arnie’s weakness was. I had to come up with a strategy that they weren’t going to expect. That race unfolded exactly how I had thought. Arnie needed to be a little bit faster going out – she did lose a little bit too much to Katie in the first 200m – but that back end was exactly what we’d trained for. To see that unfold is part of the reason that I also lost it. I’d created that plan, I could see it unfolding, and I knew how much it meant to her to try and win the Olympics. I knew how much work we’d put in over the last five years, I knew how much I’d challenged Arnie, and how much she’d challenged me. This was our first Olympics together, and to do that in that moment, was unbelievable and difficult for me to contain. And it wasn’t unusual.

HM: You have two types of grading of Arnie’s performance. They are?

DB: Outstanding and dog poo.

HM: You’re either the best in the world, and outstanding, or you’re not, and that’s just not good enough.

DB: That’s not good enough. Absolutely. That is what I believe is right for Arnie. That might not be right for other people, that’s something we created that we believed was going to be right, and she’s accepted that. I then go home and create the best program for her, which have the best sets in the world which she must execute, and the times she needs to achieve to be the best in the world. If she executes it, that is outstanding. If she doesn’t, it’s dog poo.

HM: She won the world championship in 2019, she was doing an interview post, and you got in the eyeline of the camera. What did you say?

DB: “Dog poo.”

HM: Because you could see that it wasn’t perfect, and that she could get better?

DB: Yes. The other one was when she’d just beaten the greatest female swimmer of all time, Katie Ledecky. We were a year out from the Olympics. I thought: “This could be like a poisoned chalice. She’s thinking now that she is better than what she is. She will think: ‘The race was fantastic, I’ve beaten the greatest of all time, I’ve got her now’.” I thought Arnie was going to get so many “yes” people around her, she’ll get praise, adulation, and she might lose that competitive spirit. She’ll lose that inner beast, and I’ll have difficulty over the next year trying to get her to be even better than what she is, and Katie will go back to the drawing board and get filthy angry and want a revenge. Katie will go to the Olympics for a holiday, and she’ll love that environment, Arnie has never been there, we are headed for a disaster, and I’ve got to make sure that I correct this, even though it was an hour after her win in the world championships. So that was what I said.

HM: Do you have Arnie’s program to Paris mapped out? Do you know exactly what she will do, stroke for stroke, until Paris? Is the mind forecasting that far out?

DB: No. She is right where I need her to be for now. I told her, in May of 2023, I am back to being an obsessive being. Then, everything will be mapped out, and that gives me until the Olympics, around 15 months, where I can manage that. That’s what I’ve learnt.

HM: I’ve had people ask me, ‘could you get Dean to come into the office, help our team?’ Would you do it?

DB: Yes. If they’re willing. I love talking to people who want to improve. I’m not someone that knows it all, I just know what I do. I enjoy helping people to perform at high levels. And I thrive on that.

HM: In 10 years’ time, if everything has gone as you’d hoped, where are you, what are you doing and what’s happened?

DB: The main thing now is the Paris Games in 2024. Nothing else matters. The athletes that I’ve got, I believe, can do magnificent things in Paris, and I need to make sure I’ve given them enough tools to so they will thrive. That is the toughest and most challenging environment to succeed in, but the goal is, let’s make the Olympic environment a holiday. I will need to be with my family too. I feel like I haven’t done enough self-development. I need to do that, so in 10 years’ time I can say that I have improved myself, not just the athletes. I must look inside and improve myself. In 10 years’ time, the athletes are where they need to be, they are bulletproof, but I need to make sure I have developed as a person.

HM: Your wife, Andrea. She complements your life brilliantly, and she allows your obsession to be.

DB: She is an incredible woman. She is a lawyer. When she met me, she was a Doctor of Law in her country, Slovakia. She came across in 2010, and she had to restudy to become a lawyer in Australia. She did it juggling two beautiful boys, Kaden and Dane, and me being away all the time. She never complained. She was studying and going to bed at 3am to make sure that she got her degree. She is a lawyer right now and has been working as one for over a year now. What an unbelievable lady.

HM: Does your obsessiveness and competitiveness annoy your wife?

DB: The first time I wore my competitive hat in my relationship with my wife: we wanted to do a date night – we had no kids at this stage – every Wednesday we’d go and play a game of squash and then go and have dinner somewhere. I went to her backhand right in the corner and she swung and missed it. She said: “I hate that shot, I’m not good at that.” The next 24 shots in a row, I went there. She smashed the racquet and yelled at me: “I’m never playing with you again; this is not fun.” I said, “Well, you need to improve that, you’re not good at that shot.” That was 14 years ago. We haven’t played since!