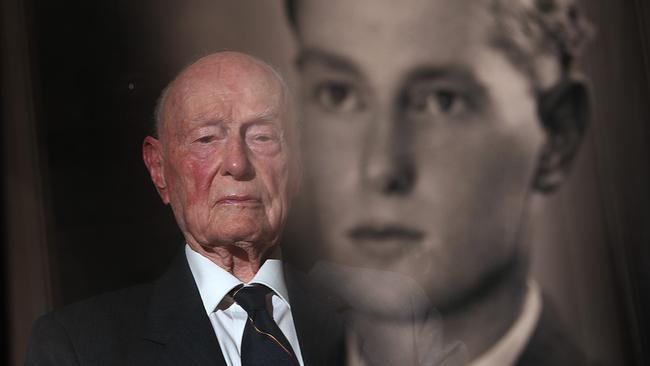

Hamish McLachlan: John Robert Bell on escaping a POW camp in World War II and making his 100th birthday

JOHN Robert Bell was taken prisoner in World War II after being shot down by Germans, surviving on rations and four-year-old potatoes. He had never spoken of his nightmarish first-hand experience, until his daughter made him write it all down.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I MET John Robert Bell two years ago at an RSL.

“Call me Jack, Hamish,” he said. And I have ever since.

WRECKAGE FOUND OF US SHIP SUNK DURING WWII

LIFE IN MELBOURNE DURING WORLD WAR TWO

Jack was born in 1917 during World War I. He fought in World War II. He was captured after being shot down by Germans, and was a prisoner of war for three years, three months and three weeks.

Jack and I speak regularly. We spoke last week for hours. It’s never long enough.

We talked about being shot down and taken prisoner, attempts to escape from a POW camp, surviving on rations and four-year-old potatoes, the mental challenges of war and settling back into life on return, ongoing nightmares, and his recent 100th birthday.

Jack remains razor sharp, amusing and fabulous company. I hope you enjoy meeting one of life’s great gentlemen.

HM: One hundred not out, and a life full of stories.

JB: Yes, I finally turned it over! I’m in my first year of life now!

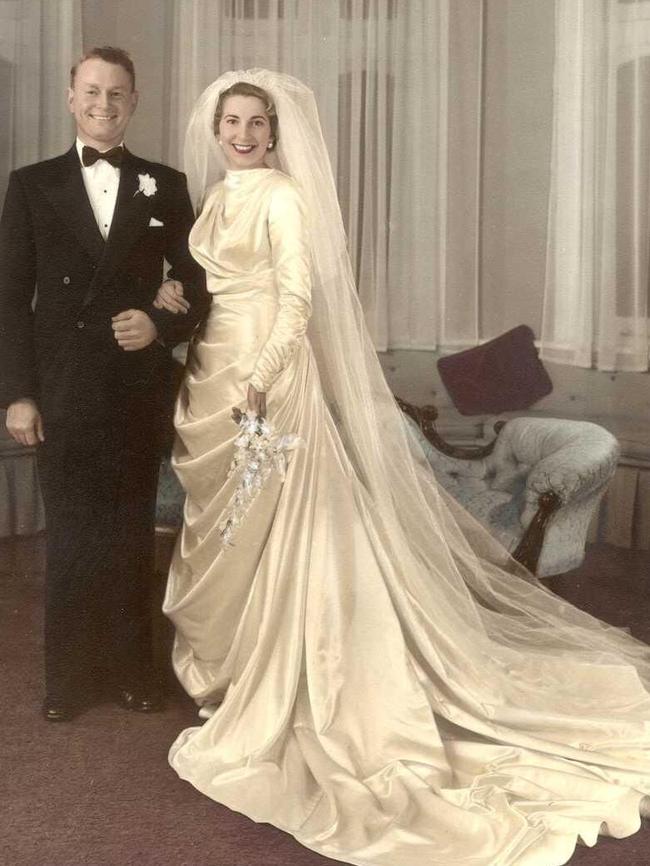

HM: Did you and (wife) Dolores hit the dancefloor until late?

JB: It wasn’t too late. It was probably about midnight by the time we got home. It was a fantastic night; I thoroughly enjoyed it. We cried, we laughed, we clapped, we did everything. It was amazing, and God was on our side! There was a fantastic storm right in the middle. All the tennis courts of Kooyong were covered with water, and the noise was fantastic. My friend Tom Roberts, from Ballarat, said “Jack, the Lord was on your side. He was welcoming you into the hundredth year of your life”.

MORE HAMISH MCLACHLAN: AFL’S CLASS OF 2017 TALK ABOUT THE GREATEST GAME

WAYNE SCHWASS ON HIDING HIS DEPRESSION WHILE PLAYING AFL FOOTY

HM: You’re looking younger now than when I met you a few years ago. You using a special moisturiser?

JB: (laughing) … Yes, I am — water! I drink beer, and I have my glasses of wine, which we enjoy every night at dinner. I don’t know how I’ve survived all this time, to be honest, but it’s amazing. One of my friends, Billy Rudd, was in the same camp that I was in Italy: PG 57. He turned 100 in December also. It’s unbelievable that the two of us, out of the 138 living POWs left, came from the same camp. It’s amazing that that could happen. There’s so few left.

HM: How many prisoners of war were there?

JB: There were about 8500 in Europe, and 23,000-24,000 in the Japanese camps, which is roughly 32,000.

HM: You were born in December 1917 — how different were things 100 years ago?

JB: I don’t remember very much up until about 1920. Whether I remember, or whether I’ve been prompted by my father over the years, I’m not sure. I remember we were taken up to see the Prince of Wales arrive in Brisbane. I remember it was 1921 when the flu epidemic hit Australia, and I was the only one walking around. The rest of the family were in bed sick. I’d take little glasses of water to them. In 1923 I started school, and Australia wasn’t an affluent country in those days.

HM: Where were you schooled?

JB: We went to school in Brisbane. I don’t recall one boy, except perhaps a couple of the migrant chaps from England, that wore shoes or socks to school. We played football, we played cricket, and we ran around in bare feet. We used to walk around the bitumen roads in bare feet. It was a laugh for us; we just enjoyed life.

HM: Were you a good student?

JB: I wasn’t a studious pupil. What was study! We didn’t know what study was, until we were placed into Mr Hopkins’ class. He used to throw bits of chalk at us and hit us over the head with the blackboard duster! He had about 50 kids in his class, so I can’t blame him too much! It was a wonderful life, and we all just had fun. We didn’t have much money, but we used to go to the flicks on Saturday afternoon, which would cost us six pence!

HM: You left school, and your first job from what I can gather was working in a clothing warehouse. Was it D&W Murray?

JB: Yes, that’s right. They had these warehouses in the capital states around Australia, and one also in Tasmania. In those days, they were the system of supply to the retail stores. Manufacturers sold to the warehouses, and the warehouses sold on. It was until about the mid-1930s, when the manufactures started to infiltrate into direct selling to retail stores. It was just a passing phase of life. All warehousing has virtually disappeared into what is now called “online buying”. That’s just life. The employment rate was fantastic in those days. We had about 120 in Brisbane, and we had five floors. We had rival companies, and life was good. We worked until lunchtime on Saturdays in the start of the ’30s. We got the 44-hour week, and didn’t work Saturday morning. We played our games of football, drank too much as kids, as all the kids do these days, but I don’t think we were as silly as they are today. There was no such thing as a drug problem; there were certainly alcohol problems, but we didn’t know what drugs were! We didn’t have a clue.

VICTORIAN WORLD WAR II DIGGER JACK BELL, 99, RECALLS MOMENT HIS MATE DIED

HM: Off topic, but you saw Sir Donald Bradman play in a Sheffield Shield match, didn’t you?

JB: Yes, that was at the Gabba! The first test match I went to was in 1928, at the Queensland Exhibition Ground. It’s a very small ground there. They were playing Queensland and it was a thrashing. Fingleton and Brown opened for NSW, and they plodded along quite well. I think Billy Brown was 60 or something like that when Fingleton got out and Bradman came in. Bradman scored 250, and I think Brown got to 150. Bradman was fantastic. He just laid into everything. He was dropped by a chap named Thompson, right on the boundary. My father and I were sitting there watching; he put his hands up, and it fell straight through the middle. You can imagine the crowd! He was a master batsman. I’ve seen Eddie Gilbert bowl him for nothing! Third ball, gone.

HM: You went from working in a clothing warehouse, to joining the army in 1936. What was it that captured your interest in the military?

JB: Financial and adventure, I think. My pay in those days, as a kid of 18, was two pounds, two shillings, and six pence — $4.50 a week. The army offered eight shillings a day! If we went on parade once every fortnight, we got eight shillings. That was a lot of money! By the end of the year we had three or four quid saved up, and that was extra. That was our holiday money! That was a keg of beer or four dozen bottles to go on our holidays in Christmas.

HM: When you joined the military, did you ever contemplate you’d ever be fighting in war?

JB: No, absolutely not. Never. It was just to get a little money, and I enjoyed the militia life, with the regimentation. We learnt a hell of a lot. They taught us how to lay guns, fire them, and raise them. It was a good life, going on the camps for a fortnight up to Rosewood, and going down to the range to shoot and see all the activity going on. It was amazing. Grooming the horses, driving them, going to gymkhanas and doing all these funny drills with the horses and the gun carriages on the back. It was a free life — lovely.

HM: You told me once you were getting very accurate with a rifle through all your training, and then you realised if you were, maybe so were any potential enemy.

JB: In 1938 we had a very good camp. I was the acting gun sergeant, and we were firing shells, 18 pound shells, over the hills about 3000 yards away, firing at registered targets like an ant hill or something. We could hit it. If we could hit things from a few miles away, I’m sure they could hit us too!

HM: Seemingly. Why did you join the air force?

JB: When war did break out, we went to the camp in November of 1939 at Caloundra, and I said to one of my mates: “Look, I’m not going to stay. I’m going to join the air force. They’re up in the air, it’s a harder target to hit!” Much to my surprise of course, all my mates came back without a scratch. They made it through Egypt, Syria, and they all came back and they used to laugh at me because I was the one that was shot down!

HM: In 1939 Germany invaded Poland, and Sir Robert Menzies announced Australia was also at war with Germany. At 21, your life was about to change forever.

JB: Yes, it was. I joined the air force on the 24th of May in 1940, in Creek St, Brisbane. We arrived there with a suitcase, and civilian clothing. We then got a train to Sydney, and stood on the platform at the Central Railway Station, and there were the NSW boys and ourselves. We were then assigned to where we were going. We were classified into the air force as air gunners, wireless operators or navigators. They read out the names of pilots, the navigators, and the wireless operators. I was called as a wireless operator.

HM: So you got allocated not because of your experience, but just because of what they needed?

JB: Exactly.

HM: The British government realised that they were going to be involved in a long war, and they didn’t have enough resources to maintain the Royal Air Force. They started the Empire Air Training Scheme, and 28,000 crew, I read, or 36 per cent of the proposed air force, were trained and supplied from Australia?

JB: That’s correct, yes. A lot were supplied through Canada, but there was a huge percentage of Australians and, I must say, New Zealanders. Their percentage would have been higher, I think, than what Australia’s was. It was surprising, but a lot of people — and I probably thought the same thing — thought, it’s a great adventure, but at the same time you were defending the empire. We declared war; you go to war. That was naturally what was important; you fought for the Empire. It was just one of those things that happened, and everybody just went away. It’s incredible when I think back, and think about how gullible we all were; we just went! We were a bit better than kids, but we weren’t very far from it.

HM: You think of 21-year-olds now, whether they’re playing in the AFL, or debuting for Australia or at the Olympics and you think, “Gee, this kid is young”. At 21, many younger, you were sent off to fight and defend an empire, and if you died, well, that was the way it was.

JB: That was it. You gave your life to your country. It was accepted. The number of young boys that died later in the war before they turned 20 was surprising. They were called up when they were 18, and they weren’t allowed to go on operations until they turned 19. They had to be in their 19th year or 20th year. They were recruited because, in those days, they didn’t know anything such as fear. They didn’t know what fear was.

HM: When it was declared by Sir Robert Menzies that Australia was at war with Germany, what was your instant thought?

JB: It wasn’t exhilaration, that’s for sure. We’d learnt and heard of the Nazi Party and what they were doing, but we didn’t understand concentration camps and things like that. They were called “work camps” or “holiday camps”, but they weren’t, of course. The atrocities committed in Poland did become known in Australia.

HM: So you were aware of that when war was declared?

JB: Not the actual desire to exterminate the Jewish race, which was their ultimate aim. We didn’t know anything about that. We knew they were being abused and tossed out of Germany and put in these work camps, but we didn’t know that they were death camps. I learnt that later in the war, of course, but it was the atrocities that we did hear about that made us realise we had to defeat this. The attitude was we needed to get over there and release these people from the servitude they were suffering from.

HM: From the declaration of war, you were mustered into the air force. Where did you first head to?

JB: Well, I’m not quite sure. We assumed that we would be going to the United Kingdom, because we were in this convoy of ships with the Queen Mary. Suddenly, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the Queen Mary peeled off and headed on to Malaysia. We continued to, and finished up in, India. Bombay. We stayed there for a month, and then we were loaded onto the Windsor Castle and taken to Egypt.

HM: You took off from Australia with absolutely no understanding of where you were going or what you were about to do?

JB: We understood that we were going to the UK, but it was only a rumour. It wasn’t fixed, but obviously somewhere in that ensuing period, something happened in the UK, so some insertion was suddenly going to take place in Southern Asia. We got to Egypt and there was all of us blokes there. The Middle East forces didn’t know what to do with us! We went to this camp, and we actually put up the tents and things like that under instruction from the British Army. We stayed there, and 25 of us were sent to Heliopolis, just outside Cairo, to be trained as cipher specialists. We were aircrew! After two weeks I was sent to 216 Squadron, but somehow my papers got lost. The four other blokes went on to the squadron, and I was sat in Heliopolis and I didn’t know what to do! Then the Americans arrived with Tomahawks. They arrived, delivered the planes on the air field to 3 Squadron, and went. They left them there, and they didn’t know how to fly this new plane! It certainly caused a bit of anger. There were a few smashed up!

HM: It’s actually hard to believe. They just leave the planes behind and say, work it out yourselves.

JB: That seemed to be what it was. I think a few of them got killed in the process of trying to fly these things.

HM: In 1941 you were assigned to RAF 216 Squadron, and you flew Bristol Bombays. Is that right?

JB: That’s right. These Bristol Bombays came in, and they were a marvellous aircraft, according to the Brits that had designed it. It was out of date before it flew! They only built 53 of them, and it was an unsuccessful bomber. It could only carry eight 250 pound bombs on racks hung outside the aircraft. The bombing was pretty terrible, and all the crew did was drop 20 pound bombs out of the flare shoot, indiscriminately over the target; they didn’t know what they were doing! Very quickly, by April of 1941, they were taken out of service and reclassified as bomber transport, which probably was the best thing they did for them.

HM: Dropping bombs indiscriminately — there is an assumption by naive people like me that things were well planned and executed and there was some method to it, but, seemingly, a lot of it was pretty primitive?

JB: It was very primitive. Sure, when an army is advancing and the enemy are grouping up and bunching, it’s very easy to bomb, because you’re going to hit something anyway. At night time, you flew over, for example, Benghazi. Well, Benghazi is a big area, so you just drop them and hope for the best. The bombing site used by the bomb aimer was very old.

HM: You have no idea what you’re hitting. Whether it’s a bomb, a house, a factory?

JB: You wouldn’t know.

HM: Horrifying.

JB: It was.

HM: You were a wireless operator, and your crew’s role was to move supplies and personnel around?

JB: That’s right, to every landing ground.

HM: Just before we get to you getting shot down over Libya, you were fired upon one day. You’d landed, and everyone was missed except your plane, but the plane continued to fly?

JB: We’d landed to supply this Long Range Desert Group (army reconnaissance and raiding unit), and there was an overhanging cliff. The plane was taxied under and a Long Range Desert Group truck was under there, which was called a Blitz Buggy. We were supplying on one side of the hill and the plane was on the other side of the hill. Suddenly two ME 109 planes flew over, and we scrambled up the top, down the other side of the hill, and they came back. They sprayed and they caught the wings of the plane.

HM: No fuel got hit?

JB: That was the amazing thing. The tanks were protected by some sort of foam that was supposed to absorb it. It was at Landing Ground 130 and there was a hell of a lot of holes. They turned around again and then suddenly they just flew off. Whether they’d run out of fuel, or whether they’d run out of ammunition, I’ll never know. We went down to the plane and the pilot started the motors. They worked, so we thought, well, we better get out of here before they send reinforcements back to shoot us off. We took off and I think that we blew a tyre. Either we blew it taking off or blew it landing, and the whole framework was screwed because of the twist. It didn’t burst into flames, and that was the amazing thing! It didn’t burn.

HM: When you were being fired at by a Messerschmitt, as a 22-year-old, you must have been having extraordinary things running through your mind.

JB: Well, all I could think of was, save yourself, son! (laughs) I’ve never run so fast in my life.

HM: Let’s just fast-forward a little to 1942. You set off on a mission to collect some brigade staff, and you were shot down by what turned out to be the 15th Panzer Division. Is that right?

JB: Yes, over Libya. We were flying to a little place called Msus, which is south of Benghazi, near the gulf of Sirte, just inland. We were there to pick up brigade headquarters staff, some injured, and we were taking a replacement aircrew, medical supplies, and I think there were a couple of medical people on board. I don’t know whether they were doctors or medics. In the desert, at night time it gets cold and the cloud bank drops. We flew at 3000 feet, then came down to about 1000 feet under the cloud bank.

HM: You were on wireless duties?

JB: Well, we weren’t allowed to transmit at the time; it was radio silence. The front cockpit was occupied by the two pilots, then there was a space where the wireless operator and navigator sat. We came down from the clouds, and we were probably down to 500-600 feet when he was coming in to land. Now, I didn’t see it, because I couldn’t see out of the aircraft, I was inside, but the pilot, Bateman, told me that as we came down this huge amount of dust was rising from the ground. We didn’t know, but we were passing over a German echelon who were part of the 15th Panzer. They were escorting heavy vehicles and all the other paraphernalia.

HM: They weren’t supposed to be there?

JB: No … according to British intelligence the Germans were down at the bottom of Sirte, but they weren’t, they were up past Benghazi and we didn’t know! We were virtually unarmed. We had one machine gun firing out of the starboard wing, but it wasn’t even loaded, because we were acting as an ambulance aircraft taking back the injured. There was this noise, with these little .3s going through the wings. The plane was suddenly filled with smoke, and this stench; the plane caught on fire! The pilot had his right leg amputated later, and the second pilot didn’t even get a scratch! He landed the plane in flames. Poor Tony Carter, my mate, was killed outright.

HM: You were hit?

JB: Yes, I had shrapnel wounds up the right leg, right arm and through my abdomen.

HM: You’ve been shot down, friends are dead, you’re injured, lying in a desert and then you are captured you and put you on the truck?

JB: Yes, the ground force of the 15th Panzer Division came and grabbed us.

HM: Who had been shooting at you?

JB: Well, I don’t know whether they’d been shooting at us, but it was from their area. I can’t say that I had any bad things happen to me. They treated us like their own. We were just lifted up and they put us onto the back of the truck. I didn’t even think anything else. I thought it was over.

HM: The astonishing thing to me is the Germans, the members of the 15th Panzer division, who you shot you to the ground, then found you and then helped you. My fear would have been that they’d be keen to finish you off, there and then.

JB: That’s what I would have thought as well!

HM: I’m amazed.

JB: They were like us. They were really regimented and they were good people. They weren’t just the scum of the earth as a lot of the Nazi Party boys were.

HM: They followed the rules of war?

JB: That’s right, they did, thankfully.

HM: Tony Carter, who was shot and killed, was a mate of yours in the plane. Had you seen someone killed before that?

JB: No. He was the first one I saw. I’d carried coffins for funerals, for boys from the Squadron, but I’d never actually seen anybody being killed. It was a baptism of fire, really.

HM: And when you saw Tony there and he’d lost his life, what did you do — how did you react?

JB: I went to him, and I was going to take his paybook and bring it back. He didn’t have his paybook with him, so I couldn’t take anything to bring back to his family. I think the worst thing I’ve ever had to do was go and see his mother when I got back from the war. That was terrible. I can see her sitting there now, looking at me. We were both weeping; we couldn’t help it. A lovely lady. Her eyes were looking at me, saying, “why my boy, why not you?” You could see it, and that’s normal. It’s to be expected.

HM: Terribly sad. You were then captured and put on a truck that took you to a basic medical centre.

JB: Yes. When we were captured, before they loaded us up, a little German medical boy came over to me, saw I was wounded, and took a piece of tape and put it on my stomach, as if that would fix it or something! He was obviously scared, the kid; he was only a young boy. I don’t remember a whole lot about that trip. We travelled from 10am to about 3 o’clock in the afternoon, down to this field hospital of the 15th Panzer division, at Anderlat. On reflection, I thought it was incredible. We were all laid out, about 20 or 30 of us, wounded on stretchers, and two doctors came around and assessed the wounded.

HM: And when you got there, they treated you?

JB: Yes, they didn’t care whether we were Italian, German, Australian, British; they just assessed on the wounds. I thought it was a pretty good and decent thing to do. I’ll never forget one of the doctors; he was a German, obviously, but he said that he was an abdominal specialist, and he’d trained in England after the First World War. He went there as part of the reparation from the First World War. He said: “I used to fly backwards and forwards to Germany on these consultations with all sorts of German problems with abdominal things. In August 1939, they wouldn’t let me back. They don’t trust me. I’ll never be the boss, I’m only second in charge”. I’ve never forgotten that. We discussed the war and he said, “The side with the most food is going to win. Don’t worry about that”. That was in January 1942. It was food that won the war. The German population by the end of 1944-45 — they were starving! They were really looking for food. It must have been shocking.

HM: And by chance, a German doctor who had been working in London operates and saves you. From there, after a little time, where do you head?

JB: He came to me and said: “Jack, I’m sorry, but we don’t take wounded back to Germany. You’re going into the hands of the Italians. You’re going on the back of a truck to a POW camp”.

HM: The surgeon’s telling you this?

JB: Yes. The Germans couldn’t speak English, but he could, and he really looked after me. He showed me how to jab myself with morphine to help me survive. I’d been on morphine and intravenous injections, and he used to come along with a little vial of morphine, break off the top and jab it in my leg. He said: “Now Jack, just jab it in there, night and morning”.

HM: He wanted to help you? The Germans were supposed to be fighting you.

JB: His compassion saved my life.

HM: How was the truck ride?

JB: Terrible. I’d been in this morphine daze for a week or so, but I remember we were on little wire stretchers on the back of this truck, and I was in a haze. There must have been five or six of us, but the canopy covered only one-third of the back of the truck.

HM: How far and how long was the trip?

JB: It took us four days to get to Tripoli, and at some point over the four days I had some shade on me. I wouldn’t know when, or how, but I did. The trick was knowing when to put the morphine in your leg. On the first night I didn’t realise, but I should have done it before I got off the truck. The Italian orderlies came and took us off the back, and they tipped me onto the stretcher in the tank, where we stayed the night. I didn’t realise, but I had 14 stitches in my belly, with two large overriding stitches. There’s one road from Anderlecht to Tripoli, only one. All the traffic was using it, so a poor old little truck like ours was pushed off into the desert. The rides were pretty horrific.

HM: There’s six of you on the back of this truck?

JB: Six men on a three-tonne flat top truck. I didn’t feel it because I was injected. I was fine, I was just in a haze. It was hot, but that night I didn’t realise that the bumping was going on. These stitches were breaking. By the fourth day I knew then what to do. Before you get on the truck in the morning? Jab. Before you get off the truck at night? Jab. I was doped for the last three days. The amazing thing was when I got to Tripoli. I was taken to this big red brick building, which was a hospital, and taken into a room on my own. This Italian nurse came in, and she would have been in her 50s, I think. She spoke English, and she said: “The doctor will come after I’ve taken all the dressings off. The doctors will come and assess what’s to be done”. She said, “How did you get here?” and I explained the trip I’d been on and mentioned the morphine I’d been jabbing myself with. She said: “Have you got any more morphine?” I had two vials left. She said: “I’m going to give you a jab, because it looks to me like you’re bleeding intensely from the wound.” I didn’t know it, but every single stitch had broken, and the two big overriding stitches that held it together had broken also. One pulled out the flesh on one side of my abdomen, which I didn’t know because I was drugged. I can see her now, her face quivering as she was working on me. I think it would have taken nearly an hour to get rid of, because the blood had just caked hard and hard and hard. She managed to get it off, and the doctor came in and said, “I can’t do anything for you”. He spoke in Italian, so I didn’t understand what he said. Then the nurse said: “We will let nature take its course”. I had this gaping wound on my belly, I was covered in this gel, and I had another bandage put on. She said: “Well, have you had anything to eat?” I told her that I hadn’t had anything to eat for days because I’d been fed intravenously. She said: “Right, well you’ve got to eat otherwise you’ll die. You’ve got to take nourishment”. She brought a little bowl of pasta to me and I couldn’t digest it. I just brought the whole lot up. She then went out into the garden, picked a couple of quinces off the quince tree, and cooked them with sugar. I kept that down, and that was the first meal that I remember consciously keeping down after I was shot down.

HM: For 10 days or so?

JB: Yeah, amazing. That intravenous stuff, whatever it was they put in me, kept me going. Those two people, the German doctor and Italian nurse, saved my life. Undoubtedly.

HM: From the hospital you were then taken to?

JB: A centre to be held at before being shipped over to Italy to a POW Camp. This was run by a big American who was in the Italian army. I’m on a stretcher, and all I’ve got on is my jacket, a shirt, a singlet and a pair of underpants. My trousers had been taken off when I’d been operated on, and they were folded with my boots and put down at the end of my bed. These desert boots were my prized pair of boots to have: they were so good. During the night, and I don’t know which night, all my stuff disappeared, and I think that big bloke was the bloke going around taking it. I finished up in what I was wearing! I was shipped over to Caserta on the Aquila. We were loaded on and, I must say, our treatment was excellent. I was at the stage where I couldn’t walk. I was a stretcher case. Fellow prisoners had to help me go to the toilet. I used to sort of struggle on my legs and walk backwards on all fours, and they’d help carry me along, and they’d bring me back. When we landed at Naples, at this hospital in Caserta, the medical man in charge was Major Martin, a British medical officer, and he had a terrible time. He had no medicine, no morphine; nothing. I can remember we were in this little four-bed room, and the two big boys used to hold the prisoners down while he operated. He cut out a pad out of one of the prisoners legs. His leg had swollen and become infected. The operating surgeon, or the nurse that he’d operated on, had left a pad in. They didn’t even give him any anaesthetic to use. That’s the sort of vindictiveness that was taking place in the back order of things. Terrible. I remember I was weighed at that hospital after we’d been there for a couple of weeks, and I was 6 stone 4. Not much really, but still, everyone else was the same. I hadn’t eaten for so long, and there wasn’t enough food to build you up anyway. I didn’t like that hospital at all. The strange thing was we had a couple of South Africans there, both amputees. One had his right leg taken off just below the calf, and the other had a hand off. It was surprising how subservient they were. One of the boys was of very mixed race, and he used to laugh and joke. He accounted to us that he was surprised that we talked to him like a normal person. He said: “In Cape Town, they won’t do that. I can’t talk like that to white people.”

HM: Is that right?

JB: It makes you think, how bad was this apartheid system! It must have been awful.

HM: Hard to fathom treating any human differently, the least of all for the colour of their skin.

JB: Exactly. It happened with the Germans in the treatment of Jews, it happened with the Americans with their treatments of the blacks, and it happened with indigenous people of our own. Later in the war, we had 7000 American soldiers come into our camp, and of course a number of blacks. Unfortunately, in the feeding of these troops, which was organised by the Germans and the Americans, it was noted by the Australian boys that the black lads weren’t getting enough food. They were getting put to the back of the queue.

HM: Still things to this day are happening that are unthinkable.

JB: There are.

HM: How many prisoner of war camps did you end up in?

JB: I finished up in three.

HM: Which was the first?

JB: PG 65, which was a little place called Gravina. It was a punishment camp, and in our little compound we had about 600 men. The rate of the death in the camp from starvation was about five or six a week.

HM: From starvation, illness, brutality?

JB: If you look in that book, you’ll see the rations that were issued. The bare rations were issued.

HM: Between the 600 men there were 14 cabbages, 11 cauliflowers, and four bunches of fennel.

JB: To last two days, Saturday and Sunday. And water was only on from 12-2pm. You couldn’t get any water before or after that!

HM: Starving, weak and thirsty. How did you pass the time?

JB: When you’re organised, it’s amazing what you can do to pass the time of day. We’d organise that we’d talk to each other in assigned places. Jack Bell’s going to talk about his life in Towong, in Brisbane, in that area, and so on. Anybody could talk. We’d just bring people out and say, “Talk, entertain us!”

HM: You think about the physical side of survival, how difficult is the mental side?

JB: The mental battle was the most terrible thing. In the end, you all had to help each other. If you saw somebody looking vacantly or you could see them “going round the bend”, as we used to call it, help them. Jolly them along. It was amazing how much you could do in a camp with nothing.

HM: Did a lot of people lose their mind?

JB: I was sitting outside a hut in PG 57 when a young man, fully dressed, walked straight at the wire and said, “I’m going home”, carrying a little satchel. Bang. Gone. You can’t do anything about it. Nobody tried to stop him. “I’m going,” he said.

HM: He was shot?

JB: Shot dead. He went over the trip wire and was shot. I can recall Socks Simmons, and he ran the two-up school with Cocky Walpole. They used to take a percentage of all of the bets. They had the privilege of buying wine and getting on the turps.

H M: So you had money in there?

JB: It was paper money. You were paid 10 liras a week. That would buy nothing, so a lot of people gambled to get enough money to buy grog or other little things. They had a little shop in the camp. One day a guard came in and yelled something, and because Socks couldn’t speak Italian, he just started waving his arm around, confused. Bang. The guard just shot him dead because he wouldn’t do what the bloke said. He couldn’t understand a thing he was saying, that’s why. Terrible, it was.

HM: You kept that guard’s number, didn’t you?

JB: He was well documented. He was given a holiday of a fortnight, and 500 liras to spend. I hope he spent it well, because he didn’t survive the war. Let’s just say the partisans got him.

HM: Tony Carter; the prisoner who said, “I’m going home”; Socks Simmons — you’ve seen too many deaths.

JB: Too many. And you never, ever get used to it. Ever.

HM: You were then moved from Italy to Germany?

JB: In a cattle truck. There were 50-60 blokes in each truck.

HM: I assume there was a camaraderie among the prisoners, and everybody tried to get on the best they could to keep alive, and keep mentally healthy.

JB: Mentally healthy and as fit as possible. For instance, in PG 57 all the boys were suffering from what’s called beri-beri. Swelling in the knees and the joints due to a lack of vitamin B. We had a few Indian soldiers in the camp and they didn’t suffer from it. Doc Levvings, who was the doctor for our area, asked them how they did it. It was because they ate a type of pigweed. Pigweed grows in Queensland and the cattle feed on it. It is rich in vitamin B, so they boiled that and drank the juice. It was put into our food and the beri-beri went. We never had it again.

HM: You were moved to a POW camp known as Stalag IVB? How many prisoners were there?

JB: It varied. There were 32 acres, and at the maximum there were 35,000 in. At minimum there was probably 18,000, but roughly 22,000-24,000 is about the stable amount.

HM: How were you allocated?

JB: The air force compound was made up of eight huts, and they had about 2100. The army next door had about 3000. The Russians had between 10,000-12,000, depending on death rate. Their ration was half of our ration, and we’d get food parcels. We gave our skilly to the Russians compound to help them. There were 33 nationalities in our camp, and one Chinaman. He was off a merchant’s ship and he was a prisoner there. It taught me a wonderful thing, because we had to get on with each other. You just had to do that. You traded with each other, and you gave to each other. I used to get cigarette parcels from England. I was supposed to get 1000 a month, which I never got of course, but I probably got 800. Half of that ration I gave to the hut commander, to go to the escape committee and to the hospital, to bargain with to buy food or whatever they wanted. I shared the rest with my mates. Cigarettes in Germany. That was the money. I’ve seen one cigarette sell for one pound sterling. In the rations we used to get tins of 50 cigarettes, occasionally in the Red Cross parcels. I didn’t smoke. I stopped smoking because I had pleurisy in Italy, and Doc Levvings said to me, “Well, Jack, it’s very simple. You can stop smoking, or keep smoking and die”. I chose the former.

HM: What was the main source of food?

JB: There was supposed to be 14 pounds of potatoes, per week, per man. The only difficulty about it was the potatoes were four years old. The system of refrigeration in Germany, for slave workers, was done by digging big pits, about 2m deep, on a V-shape, lined with straw. You’d then put all the potatoes in, cover it up with straw, in during winter so it froze. They’d last two years without any problem, but by the third year they were starting to go off. By the fourth year there were a lot of black spots, and very little white spots.

HM: Not the sort you’d pick out of the bin at your local supermarket.

JB: You’d steer well clear! What we used to do was put them on the concrete floor of the cookhouse where the cooks would hose them, and put them in the vats and cook them. You ate the white part and discarded the black part. That’s all you could do; there was no such thing as mashed potatoes!

HM: Was there any meat?

JB: It’s a bit contentious, that. Horse meat, occasionally. For our hut we had six horse heads and a single four-quarter pork for 220 men for two days. The horse heads had very little meat on them, so we smashed them up on the cookhouse floor, cooked them, and served them. If you got a bit of bone, bad luck!

HM: You must appreciate when Dolores whips up a batch of burnt butter biscuits these days!

JB: Oh yes, burnt butter biscuits is the favourite. It’s a funny thing. I can laugh about it now, but food back then was a very serious matter.

HM: Did you think you were going to starve to death?

JB: At times, yes. Often, actually.

HM: You were a POW for three years, three months, and three weeks. How much of it were you starving?

JB: At least half of that I was hungry. The rest of the time we managed to get extra Red Cross parcels and things like that. It was deliberately done. Let’s be honest about it, they didn’t want fit men as prisoners.

HM: To take on the guards and try to escape?

JB: That’s right, and enough escaping went on. Tommy Fielder, he escaped five times but got recaptured each time. He was very determined man.

HM: How would he escape?

JB: Well, he’d go out with the work party and just disappear into the forest. They went out to get wood to bring back for the fires. He would take off, but he would always be caught in the end.

HM: You watch Hogan’s Heroes and people are digging. Was there any digging to get out?

JB: Yes! In Italy, 19 people did get out through a tunnel they dug in Compound 3. They were all recaptured, too. The Italian camp commandant Colonel Calcatera said that nobody would escape from that camp. He was pretty right. Norman Ginn, who is still alive, he lives in Adelaide — Normy. He was short, about 5 foot 6 inches. How he got into the air force I’ll never know. Gill Lindschau and Normy were good friends in Stalag IVB and with a group of friends decided they would tunnel out of the hut used as an amenities hut, under the wire, out onto the parkland, and into the forest. They did very well. Gill spoke German, but he never let on in camp that he could speak German. He could understand what was going on. He was the carpenter and he used the bed boards from our beds to shore up the sides of the tunnel, because it was very sandy soil in the prison. It was deliberately put there because of sandy soil. We used to take off the plywood from the Canadian Red Cross food parcel to support the earth above it. Unfortunately a farmer drove over the exit just outside the wire so no one escaped.

HM: It’s not often you’d have someone trying to break into a prisoner of war camp. That happened.

JB: That did happen. In November 1944, a lady broke into the camp.

HM: Florence Barrington.

JB: That’s the one. I didn’t know anything about it until 1973, and I was in the hut next-door! There were a minimum of 22,000 men, and 2000 in our compound, but there were six men in hut number 34A that looked after that lady. Her son was in that camp.

HM: She broke into the POW camp and lived there for a number of months to see her son?

JB: Yes. Her husband had died, and she and her son Winston were holidaying in Austria at the beginning of the war. She was too ill to return to England and was allowed to remain in Austria under Gestapo watch. Winston returned to England and became a pilot in the RAF and was shot down and became a prisoner in Stalag IVB. She wrote to the commanding officer seeking permission to come and visit him. Surprisingly permission was granted and she moved to Muhlberg Hotel and visited with her son. By the end of October 1944, the Escape Committee decided to bring her into the camp to keep her safe. The French POWs smuggled her in dressed as one of them from their party. She sneaked in, lived effectively in a cupboard, and was there for a few months, close by, and I had no idea. Only six men knew that she was there.

HM: You actually can’t believe it’s true. You survived starvation somehow, the risk of losing your mind, and being shot. A day finally arrived where liberation occurred. How did you find out the war was over?

JB: We knew the war was about over around the middle of April. We had the BBC radio on in the hut, and we knew that three Russian armies had circled the German armies and there was no escape. It had to finish. Montgomery was coming through, and Patton had gone to the bottom of Europe, so it was inevitable. We knew by the end of April that it was all over, because the Russians absolutely swamped the area that we were in. It was inevitable. What to do? We were told that we would be released, but what the Russians didn’t say was that we’d be released when it suited them best. They wanted to get their prisoners first. As I learned later, in 1984 the BBC put out a documentary of Russia’s POWs returning home. One of my mates, Jock Watson, actually saw this. A colonel of the Russian army used to come and watch us play cricket, and he went to Sandhurst. I can remember him telling us, “We won’t get back to Russia, you know”. I said, “Why?” He said, “Well look, we’ve seen how the Western world live. All these peasants who have come here, they want to live like you do. We won’t get back”. Not one of those people got back. I remember the colonel coming into the camp and saying to the Russians: “You will make your way back to Moscow, on foot. You will treat the Germans exactly as they’ve treated you, and you will live off the land to get home. Walk. You will not be given any lifts.”

HM: When were you released?

JB: On the 15th of May we walked out. We had a bit of stuff left in our Red Cross parcel, and we’d found a case of Hennessey brandy at the back of a grocery shop which we halved with the Russians for half a case of tinned meat. Five of us drank the first bottle of brandy, and we all got drunk. Then we decided we’d go, and we walked out. Once we got out of the gates, we just kept going, we didn’t turn back! They weren’t particularly worried; they never counted us or anything. We got lifts with the Russian soldiers who were on trucks and things, and they were fine. When we arrived at the Elb River a big American top sergeant said, “Come!” First he gave us a box of army rations and the following day they flew us to Brussels. They killed you with kindness; they’d give you anything. Of all the attitude they had, they did have some good guys and some bad guys. Arriving in Brussels we were met by an army of ladies, armed with fresh white bread. It just tasted like beautiful cake to us! I wouldn’t have had white bread since before I went up to the desert. Four years! Amazing. Beautiful. We stayed in Brussels a couple of days, and flew back to England.

HM: What was the hardest part of integrating back into day-to-day life, given what you’d seen and heard?

JB: It was terribly difficult. We were all euphoric. We went away, we saw terrible things, and lived in terrible ways, and then we were back, and we were home.

HM: What was the advice to help you cope?

JB: When we were about to disembark to go up to Brighton, and up to Liverpool to get on the ship, a doctor came out and spoke to a few of us and said: “Your life expectancy is between 50 years and 60 years. Get on with your life. Go back, and go to work. Don’t discuss your time as a prisoner with your family. Don’t talk about it at all.”

HM: You were encouraged to try and forget everything, bury it, put it behind you and move on?

JB: Move on, you’re free! Our parents were told not to discuss it with us. That was the greatest mistake that was made, because we didn’t have a release valve. So what did we do? Many came back, and we had friends in every city. We’d drink, and talk to each other, and I think that was the best way to put it behind us. I met Dolores in 1946, but didn’t get married until 1954. I couldn’t bring myself to marry.

HM: And you didn’t really speak about any of your time until your daughter insisted you wrote it all down?

JB: It was blocked — completely blocked. I tried to suppress it all.

HM: Even with Dolores?

JB: I never talked about it at all — I wouldn’t talk about it. I couldn’t. It was too hard. Too emotional. Too difficult.

HM: It didn’t help you to talk?

JB: I couldn’t do it. They didn’t know what war was about. It’s unfortunate, but that’s how you think. They didn’t understand, so you don’t try and make them understand.

HM: I’ve read all you’ve written, and I still cannot get any sense of the horrific atrocities you would have seen.

JB: It’s very hard. It’s one of those things that’s happened, it’s unfortunate, but I’m very happy and pleased now that I have written about it, that I’ve talked about it. I was only one of many. The POWs in the Japanese camps must have had a far worse time than I had. I’ve got a couple of mates now: Colonel Hamley and Frank Hollandstoback, who are in their 90s. They’re very ill now. They’re on their way, but gee, what they went through was 20 times worse than what we went through.

HM: Your daughter Sandra made you write it all down — she said she didn’t know anything about it, and made you.

JB: Sandra was the one who was able to get me to open up about my life. She came to me in 1987, and I’ll never forget it. She said: “Dad, Mum knows nothing, I know nothing, your grandkids know nothing. For goodness sake, write it down”. It took me three years, but I’m so glad that I’ve done it, and that I can talk to people about it. I get emotional and I can’t help it. My mind wanders back to what was really happening. I’m hoping I’m helping somebody.

HM: Do you still have nightmares?

JB: Oh yes, still, yes. It’s a strange thing, they’re not nightmares where I’m escaping from the camp, a lot is about getting back into the camp. I can’t understand why. Sometimes I’m talking in some situation where I’m the one that’s being subjected or punished for some reason or another. It’s one of those subconscious things that’s in the mind of all people that suffer from anxiety. You’re not quite 100 per cent and you never will be.

HM: Seventy-five years on.

JB: Yep, just the same. I can sleep and I sleep well, but somewhere back there are the demons.

HM: Dolores is an amazing woman. She must lay next to you and see you having the nightmares. I read that every now and then you get violent in the night, and end up hitting Dolores accidentally.

JB: I do, yes. I don’t know why it happens.

HM: What was the worst of everything you experienced?

JB: I think one of the worst things that ever happened to me was in Brisbane. We went to join the RSL because they had a bar. I can understand this, but they couldn’t just suddenly take 100 people into their RSL. They didn’t have the facilities or anything else available. One day a woman in the street said to me — and this has been said to other boys — “Why did you go and fight in Germany? Why didn’t you fight against the Japanese like our boys?” I was a prisoner of war just after the Japanese invaded! What a thing to say. It’s a horrible thing to say. “You shouldn’t have been overseas.” They were the most hurtful things ever said to me.

HM: People say some hateful things.

JB: You forgive, but you don’t forget.

HM: When you came back, did you turn to the drink to try and forget?

JB: Oh, of course.

HM: Too much?

JB: Too much. Much too much. In 1957, superannuation was a big thing starting up, and it started in the company that I worked for. Most of us in that company were ex-service people. We used to have a beer, and I never discussed my life story with anyone. When we went to the doctor to be assessed for superannuation, he said “Do you drink much?” I said, “Oh no, I have a couple of beers after work, and go home and have a bottle of beer with my wife, and drink a glass of wine”. He said, “A couple of beers?” And I said, “Well, maybe a few.” He said, “All of you blokes drink too much!” He said to me, “One in six Australian men are alcoholics. You don’t realise that, but if you have more than four drinks a day, you’re an alcoholic.” Today, I still have a couple of stubbies a day, with a glass of wine at dinner. I’m still an alcoholic!

HM: You can do whatever you want at 100, Jack!

JB: I still go for my walks, if possible, every day. If I didn’t do that my legs would freeze up, because I’ve got blocked arteries and aneurisms. The specialist said to me: “10 people have come to me suffering from blocked arteries and aneurisms in the legs. Eight survive, the ninth I can operate on and save, and the 10th just dies because they don’t do anything. Keep walking.” That’s all you’ve got to do — keep walking!

HM: Just keep walking … and Jack, thank you from all of us, for everything you’ve done.

JB: Thank you, Hamish. It’s a privilege to talk to you and I’d like to ask those reading this to support the upcoming RSL Anzac Day Appeal.

You can at anzacappeal.com.au