Hamish McLachlan: James Reyne opens up on his accidental career

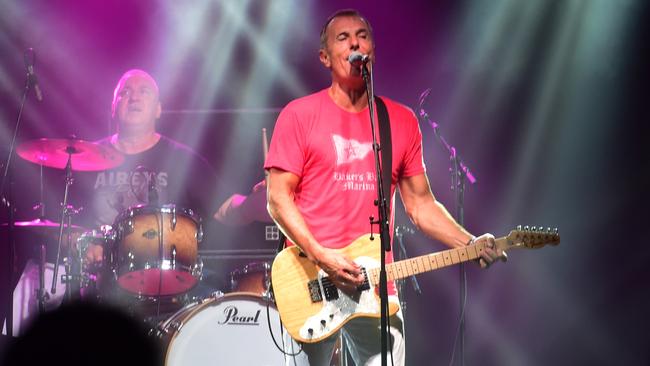

Aussie singer-songwriter James Reyne has created some legendary rock and roll anthems over the years. He tells Hamish McLachlan his career was an accident and reveals why he never tires of playing to a crowd.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I think a few of us have dreamt about being a rock star at some point. The front man of a band — crowd singing with you, hanging off every word. James Reyne started writing in his bedroom years ago in 1970, and has never stopped. With a few mates, he formed Australian band Crawl and produced some Aussie rock and roll anthems. Reckless, Errol, Boys Light Up, Downhearted, Beautiful People … if you are my age, hearing them brings back great memories. We talked about an accidental career, dropping out, beers at 7am as part of greater learning, the rush of performing, miles in the car, the best act he’s seen and his new music.

HM: Just for transparency, you need to know that my wife grew up with a poster of you on her bedroom wall …

JR: Well that’s a little surprising, and very nice to hear! I assume you’ve taken it down!

HM: I have, but it caused an argument! The bedroom is where you do most of your writing, isn’t it?

JR: Yeah, it is pretty much. In the corner of my bedroom is where I have my desk, I’ve got a piano there, and a couple of acoustic guitars. It’s a good spot as I look out over a paddock, there’s a lot of trees, and it helps the creative juices. It’s a nice place to be. Most of my songs over the past 20 years or so have been written from there.

HM: Did you ever think writing songs and singing them could actually pay all of your life’s bills?

JR: No, never. I never had any ambition as a kid to become a singer, I would just write songs because I liked doing it, and I still do, I do it for fun and it amuses me. I write, and if anyone else likes what I write, well that’s a huge bonus. But I never, ever thought I would do what I’m doing now for a living. Even after I’d made a couple of records, I thought, well, this has to stop somewhere soon. But luckily, it hasn’t.

HM: How old were you when you started putting words on a page, and strumming?

JR: About 13 or 14 I guess. A few of the guys I hung around with growing up played guitar, so I learned a few basic chords from them. It was just something I did for fun and to fit in.

HM: There was always music in the house growing up?

JR: There was a record player with a lot of jazz being played on it. My father played a lot of Fats Waller, but he also played a lot of Michael Flanders and Donald Swann. Our parents listened to classical music, a lot of Gilbert and Sullivan, and my mother still sings. She was often in productions, so music was always around and in the air. It was taken seriously. There was a show called My Music that my parents would listen to on the ABC, and if it was on, you had to be dead silent! So there was a love and respect for music for sure.

HM: How did Australian Crawl form?

JR: Randomly, really. There were four or five of us who hung around as friends all the way through secondary school. We all played a lot of sport together, and we were all big music fans. We had little bands that weren’t any good — we’d only play in our parents’ lounge rooms! It was only in the first year out of school that we started doing a couple of our own gigs down on the Peninsula. We ran them ourselves. Twenty would turn up, then fifty, then a hundred. In those days you’d hire the Moorooduc Hall, or the Tyabb Hall, and it was fairly cheap. Even then, I was at University and Brad Robinson was playing football with Hawthorn. We were all doing other things, but as we were, we started to get more and more gigs. There was an agency in Melbourne that heard about us and offered to represent us, and then we started getting more and more shows in Melbourne, and then it got to a point where we had to make a decision whether we kept doing university and football, or, take the band seriously. We opted to stick with the band and see what happened, and it went well.

HM: Brad (Robinson) presumably rings David Parkin, or whoever was coaching him at the time and says, “I’m off to play music — thanks for everything though”.

JR: Seriously, I think it was as simple as that. Brad was 6 foot 6 and was put under the wing of Don Scott at the time. He was a really good footballer. They had their eye on him for the future, so they were treating him as a long term project and trying to muscle him up a bit. But he decided to be in the band, rather than play footy, and I’m very glad he did!

HM: Law at Monash, and then Victorian College of the Arts for you?

JR: Both badly! I started off doing law, but did no work, so I ended up swapping to arts ... sadly, the work ethic didn’t change, and I just dropped out. Then I spent a lot of my time doing plays, and my mother said, “They’ve started this new drama school at the Victorian College of the Arts. They’re auditioning”. I went along, and got in. It was a three-year course. I did that for two years and just one week of the third year. But by then, the band had enough work that five days a week of drama school was a grind, so I dropped out of drama school too! On reflection, I was a classic dropout. Not good!

HM: During your Arts education, you spent some of your time at the The Waterside? I hear it opens early.

JR: I thought you went to drama school to study plays, but a lot of it was a much more alternative kind of study, studying the Stanislavski method. We did a play called The Lower Depths, which was written by Maxim Gorky, a Russian play written in 1890. It was all about the dispossessed of Russian society then, the people who were poverty stricken. To do our research for this play, we had to go out and spend some time with the winos of Melbourne. It was only a day, and it was ridiculous because you can picture all these little drama students gathered on the steps of Flinders Street station at 6 o’clock in the morning before heading to The Waterside. In those days, that was the only pub that was open that early. It was for the guys that worked on the docks — they’d finish their shift and come have a beer. We started there, and we ended up in Brunswick at some other pub. I was pissed by 12.30pm and went home. The next day we had to sit around and discuss it!

HM: You were good enough as an actor to get the role in Return to Eden, where you fed your wife to crocodiles …

JR: What a role. That was more luck and circumstances. Hal McElroy, who was the producer of Return to Eden, had tried to cast a character who was a one-dimensional, professional tennis player, who was an arrogant jerk. They couldn’t find a guy, but then he saw a picture of me, and he thought, “That’s our guy! We’ve found him!”

HM: But your love was music. Who came up with the name Australian Crawl?

JR: I don’t think anyone can really remember. Four out of the five of us in the band swam competitively, and obviously Australian Crawl is a swim stroke — it’s just one of those names that came up when we were brainstorming a name for the band, but there wasn’t a specific reason for it being thrown up, or chosen! There were 20-odd names, most of which were as arbitrary and just as silly. Australian Crawl for some reason was chosen by us all, and just seemed to stick, but to this day I really don’t know who chose it or why we did.

HM: The debut album — Boys Light Up — it went five times platinum and was in the charts for 101 unbroken weeks. Did you have any feel that it was going to become enormous?

JR: No, none at all, we just thought we were lucky to be making a record. Not for a second did we think it become life changing.

HM: What changes for you after that? Everyone that I speak to says nothing changed for you in terms of demeanour — you remained humble, level-headed ...

JR: You hope you don’t change. We were a fairly cynical bunch and all made sure no one got ahead of themselves. You just carry on while everything is getting bigger around you. Saying you’re in a bubble is a bit of a cliché, but you are a little — you are writing and singing and driving to the next gig, just carrying on. You just work hard, making the most of the momentum. We were doing six nights a week, eleven months of the year, all over the place. We’d spend a lot of our time in cars.

HM: Lots of miles.

JR: Too many. My memory of Australian Crawl is cars and driving. We had no mobile phones, computers or sat navs or anything in those days, so you just drove, with the map on your lap, to the next gig. Wednesday night you’re playing in Adelaide, and Thursday night you’d be in Sydney.

HM: Did you have good management — did you make the most of your success?

JR: With the success came some money, and we got to a point where we realised we had to run the band as a business. Fortunately, Brad’s brother was an accountant, so he looked after all of that for us. Everyone got the same wage, for 52 weeks of the year. Any money above and beyond that, was put aside for the band for later on.

HM: Do you feel it would it be harder or easier if you were starting over now?

JR: I think harder. There are a lot more platforms to be heard on, but I just think it’s harder to get heard above everyone else now. There’s no national show on television where you can go and perform which used to be the launching pad.

HM: The TV execs obviously know what rates and what doesn’t, I guess you can get it all on your phone and your tablets now?

JR: Maybe — there are a lot of young bands that have huge followings that I wouldn’t know about, and they’ll go and sell out Rod Laver Arena. They are obviously making the platforms work for them. Tones & I was playing on the streets of Byron a couple of years ago. You can have huge distribution quickly if you can make it work.

HM: I read one of Mick Jagger’s books, and he said something like “I could give up the drugs, I could give up the grog and I could probably give up the women, but the one thing I could never give up is the feeling you get from the fans”. Is that what you thrive off the most?

JR: Yep — absolutely. Nothing beats playing something on a night when everything is working, when the band is really firing and the crowd is right there with you. Nothing beats that. That’s why you stand up the front and play. I get a great deal of satisfaction out of finishing a song that I think is OK, or worthwhile, but nothing beats playing that song in front of a whole lot of people, and then seeing them enjoying it. That’s the ultimate feeling. And it’s reciprocal, because you get a real rush from them. You really get that feeling, and you never get tired of it. You wouldn’t be human if you got tired of it.

HM: What’s your best moment you’ve had on stage?

JR: I remember there was a venue in Sydney called The Manly Vale, and we did a gig there one day. In those days, it probably held 2000 people, but legally closer to 800. I remember being on stage at that place, and there were literally people hanging off rafters and sweat was dripping off the roof! You could see it, and there was steam because there were so many people there, just so up for it. It’s moments like that that you don’t forget. There were people lying on the stage as there was nowhere else to go.

HM: Because you have the highs, when you’re waiting for a gig or in between gigs, or trying to write the next album, do you have lows?

JR: That’s the nature of showbusiness. You know this. Any form of showbusiness, which includes anything, rock and roll, TV, film, radio, theatre, it’s the very nature of that business that there will be highs, and there will be lows. I accepted that early. I’ll have writer’s block, but I’ve learnt that it does come back again…eventually.

HM: Writers block. You had “The Yips”, as you’ve put it, singing wise. The brain can be powerful, both ways.

JR: The yips I had were related to a throat issue, nothing serious, but the actual physical issue I had was zapped, they got it and it was fine, but my muscle in my neck spasmed, and I couldn’t sing for a little while. It came good and I was fine, but I got it in my head that I wasn’t going to be able to, and I had to convince myself I would be able to. The only analogy I can think of, is that it’s like when sportspeople get the yips, like when a golfer suddenly can’t putt. I had the yips for three months!

HM: When you got on a roll writing, how long would it take you to write Boys Light Up, or Reckless? Is that a week, a month, a day, an hour?

JR: Those two songs, for memory, came really easily. It just fell out. Often, the ones that endure are the ones that seem to fall out, yet there have been other songs that I’ve written that I think are just as good, and the verse might take a year.

HM: Is there a song that you wrote that went berserk that you didn’t think would, or should have been enormous that didn’t?

JR: Plenty that I thought should have been enormous that didn’t! I didn’t think Reckless was that good. When other people said they liked it, I thought, really? I thought it was a bit weak and didn’t really hang together.

HM: Do you have a special guitar in your bedroom?

JR: I have a guitar that I’ve written most of my songs on for the last twenty or so years.

HM: Is that Brad’s?

JR: It’s Brad’s. An old Black Martin guitar, a beautiful guitar. It’s one of a couple of things I know he valued. He loved that guitar, and now I do too. I always thought, after he passed away, rather than it just sitting somewhere gathering dust in a cupboard, it should be played. I bought it from his family — I feel lucky that I have it.

HM: What was the last drink he offered you?

JR: Ha! The poor guy was bed bound, in his last stages of battling lymphoma, and he had a bottle of liquid morphine for his pain. He said, “Do you want a slug?” I said, “You’re a sick guy, I’m not going to take your medicine from you!” That’s the kind of guy he was. I had to think about it, but I wasn’t going to take it from a sick man.

HM: He sounded a fun man. Who’s the best performer you’ve ever seen, musically?

JR: There have been many — I think the best rock show I’ve ever seen, as a rock and roll show, was in the late 80s — it was Van Halen at Madison Square Garden. Their song Jump was number one song across the world, and David Lee Roth was the best rock and roll front man I’d ever seen. He was amazing — he really had an aura. I’m old enough to have seen Muddy Waters who I thought was amazing. There was just power in him standing there. I saw The Police at their height too — Sting was incredible — and I saw Midnight Oil playing in Sydney before they were big. They were a really powerful band.

HM: The two bands I’ve seen who drag you in are The Killers, and Foo Fighters. Brandon Flowers and Dave Grohl are so charismatic …

JR: They just know what they’re doing, they’re at home. They’re most comfortable on stage, they take you somewhere you love.

HM: You’re quite a reserved, quiet guy who’s a front man in your spare time. It’s quite a dichotomy.

JR: A few of the people I know who do what I do, they’re fairly shy socially, but you put them on a stage, and you go, “wow, who is that?” A lot of actors are like that. If you meet them socially, they’re actually quite shy. Mind you, there are some actors who aren’t so shy…

HM: Nineteen top 40 hits, Hall of Famer, OAM. What would you be doing if you hadn’t started strumming, do you think?

JR: Maybe I would have been a battling actor, or gone back to law school and become a lawyer, or a teacher? I had no plans for anything — I sort of just kept writing and singing and no one said stop!

HM: Were you living in London, and then suddenly on stage outside the French Embassy amid a protest around the French testing nuclear bombs in the South Pacific?

JR: I did — that was weird. I went down because I was living in London at the time, and there was a big demonstration outside the French Embassy, mainly Australians and New Zealanders, because that’s where they were going to test. I went down there to be a part of the crowd, and somebody in the crowd spotted me. Suddenly, there was a guitar thrown into my hands, and I’m hoisted up on to the stage. I’ve got this weird old guitar that was out of tune, I madly tried to tune it, and ended up singing Reckless. It was amazing. I thought “If I hadn’t written a couple of these funny little songs in my bedroom, I wouldn’t be doing this!”

HM: It’s crazy.

JR: I remember walking down Kings Road once in the days of Walkman’s, and a guy was walking towards me with his headphones on. He spots me, takes his headphones off and puts them on my head. He’s listening to me. He just looks at me and says, “Holy sh--!”

HM: Tell me about Toon Town Lullaby.

JR: It’s a new album. I had an EP about four years ago, and I just had enough songs that I thought I’d make an album. I’m under no deadline pressure to make records anymore. I’m truly independent, and I pay for my own recordings. It’s distributed through Mushroom, but I pay for it. It came out on Friday, and it’s a fairly personal record, by and large. A lot of the songs aren’t about me per se, but about stuff that I’ve been through. There’s a song about Brad on there, there’s a song about when I lived in Los Angeles.

HM: Is the song about Brad, The Tallest Man I Ever Knew?

JR: Yes. It was just a phrase that popped into my head one day whilst driving. I don’t know why I thought of it, I just knew it had to be a song about Brad. We had a lot of weird adventures together. It was really an exercise of writing down a lot of in jokes that only he or I would get, but also trying to make it readable and listenable enough so it feels like a good song.

HM: These days when you make a record and an album, is the bulk of the purchase online?

JR: The bulk of the purchases are through the stream logs, Spotify, iTunes. That’s where most people listen to music now. That whole notion about music being free, it’s not specifically free, that’s why the royalty aspect is not what it used to be. Playing live now is how we make the income, and that’s why in the current climate it’s tricky because we rely on mass gatherings of people. We’ll be the last to go back to work.

HM: Pre-COVID, how many gigs would you have been doing a month, or a year?

JR: We were sitting at the airport when we got the phone call saying it was all over. We were in the middle of a tour called the Red Hot Summer Tour. We were doing two a weekend, including a travel day there and back, in front of 10,000 people. That’s what we were doing when we went into lockdown. We used to do 150 shows a year, right up until a few years ago. I’ve purposely tried to do less shows, but bigger and better shows. My joke used to be if there was some idiot in the audience ... let’s work it out. I’ve done this for 30 years, let’s say I do 200 shows a year. 200 times 30, that’s 6000. There’s usually a d--khead in each show, so that’s 6000 d--kheads I have to deal with. I’ll turn, and turn the crowd on them.

HM: (laughs) There’s always one hater …

JR: Recently we were doing acoustic shows, and some guy started getting mouthy. What are you getting mouthy for, you’ve paid the money! Why would you pay money to come along and get mouthy with me? I’ve got the microphone, so I’ve got the power! Why would you not want this to go well?

HM: There’s a lot of acidity out there!

JR: There sure is. They just want any excuse, or platform, to vent. We don’t care what you think, and you don’t know what you’re talking about.

HM: The video clips from Aussie Crawl days … I was watching Errol this morning when you’re all in the surf and the spas …

JR: Oh god! The story behind that particular video, is at the time, one of the guys in the band, Bill, knew a guy called George Muskins, who went to school with us. He was a few years older than me. He worked in advertising, and he made the Coke commercials during that time. Because we were considered these surfy boys from the Peninsula who hadn’t paid their dues, we thought, ‘let’s take the piss and get George to make our own Coke commercial’ A couple of guys surfed, we swam, we did a bit of water skiing. We just thought, let’s get Aussie Crawl doing every single water sport that we could think of, plus a waterslide. We hired all these girls, so we’d be in bed, in the spa, and all their boyfriends came and sat in their cars waiting for them! Everyone thought we were so up ourselves. Let’s have us running in slow motion across the beach like young stallions. It was just a joke, but it backfired because people thought we were being serious!

HM: One gig, full house anywhere in the world, where would you want to play?

JR: You will be surprised by this, but somewhere local like The Great Hall down near Shoreham, a funky old wooden hall, packed with surfers, on a hot summer night. That’s my go — I’m a Peninsula guy.

HM: Back in your own bed that night.

JR: Perfect!

Toon Town Lullaby is available now.