Hamish McLachlan: Fen McCall on her 12 years as a drug addict, and how she got through it

Fen McCall was a drug addict for 12 years, living and working while always wondering where her next hit was going to come from. She tried and failed to quit over and over. Now, she tells Hamish McLachlan how and why she finally got through it, and what life’s like after four years clean.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

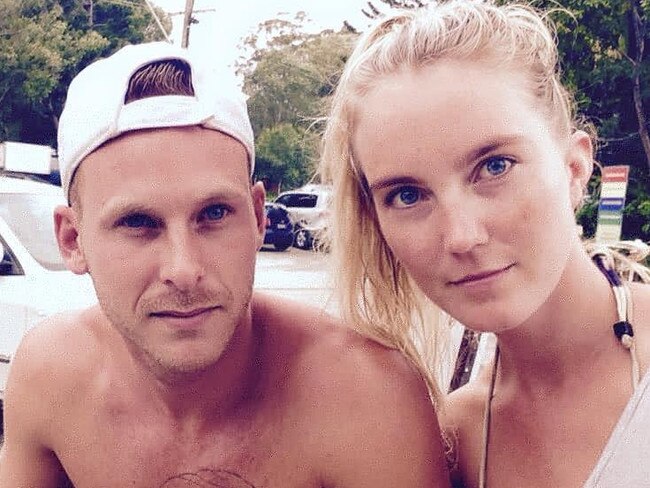

Fen McCall and I met four years ago in a boxing gym in Richmond.

She was a week from being one year clean after more than a decade of drug addiction.

She hoped she could stay clean. She wasn’t sure. Fen is now approaching her fourth year without drugs.

We sat and spoke about how her life had spiralled out of control, the agony of losing a baby, the death of a friend, and the complete rebuild of her life.

MORE HAMISH McLACHLAN:

BOY FROM BROADY TO EDDIE EVERYWHERE

SECRET TIPS TO HAVE A GREAT DAY

HM: Fen, good to see you again.

FM: Thank you, good to be here still in a good, healthy shape!

HM: You and I met in a gym a few years ago. At that stage, you were a week from being one year clean, after a decade of addiction.

FM: Yep, longer even — 12 years or so.

HM: We’re approaching four years clean now so we thought it would be good to check in. Firstly, a bit of a recap for those who aren’t as familiar with your story. When did you first use drugs?

FM: It sounds so crazy now when I think about it, but the first time I used drugs was when I was 12. I smoked a joint.

HM: You drank a little bit first?

FM: Yes, and I do consider alcohol as a drug. I started drinking around 12 as well. I went to parties with friends and we snuck into our parent’s alcohol drawers, and from such an early age I just wanted more. I loved the feeling, it felt like a relief and it felt good. I felt confident, it was awesome. I just wanted more.

HM: Alcohol and marijuana at 12 — when did that progress to something harder?

FM: I was about 15 or 16 when I tried speed, and it is a little bit hazy, the exact whens of it all, but pretty much as soon as I had an opportunity to try something, I would.

HM: No reservations?

FM: No reservations.

HM: And we’re talking about someone who had been given a lot in their life, privileged family, well educated …

FM: Private school, sporty, pretty smart, but there was just this feeling inside, of being alone and that something wasn’t fulfilling me.

HM: You thought life would be better with drugs.

FM: Exactly.

HM: How do you come across speed at 15?

FM: I’ve got two older sisters, six and twelve years older. When I was twelve, I had an 18-year-old sister and a 24-year-old sister, and a lot of my friends had older siblings as well. For some reason I was just in a group of people that gravitated towards older teenagers, or young adults, and that’s how we got introduced. Either I snuck it from them, or we’d find someone that would be willing to say “Here, have some”.

HM: I get terrified of the thought of it, whereas you were excited by it.

FM: It still excites me, to be honest. I’m four years clean and still think it seems really exciting. The idea of getting out of my body, kind of, and forgetting my responsibilities and worries, just for a moment.

HM: Is it dangerous, you talking about it?

FM: No, not at all. I feel like I’m now in a space where I’m really aware of the excitement, and the feeling it would give, but I know very well that it’s not what I want with my life. Now I want responsibility, and I want to be a good mum, and I want to achieve things. For me, if I’m using drugs, that doesn’t happen. It is totally destructive to the life I want.

HM: So alcohol and marijuana at 12, speed at 15 — when did things progress to ice and heroin?

FM: I discovered ecstasy, going out, partying, MDMA — pretty much everything, which I thought was really fun at the time. I wasn’t afraid to try anything, I thought it was all amazing and cool, nothing to worry about. If there was an opportunity I’d be like, yep, I’ll take it. I had fake IDs, so I’d go out clubbing when I was young, and I found people that had meth, also known as ice. They’d ask if I wanted to try some, and I did. That became my drug of choice initially, and that’s what I wanted to use all the time — ice. I had all these other deep-seated issues, like body image issues, and when I used ice I found that I wasn’t hungry and didn’t need to eat. That seemed to tick that box and also keep me up for hours, wanting to party, go out and dance. At that age that’s what I wanted to do with my life, then I met my partner, Sam, who I’m still with today.

HM: … and the father of Mickey.

FM: Mickey, yep, my baby. Sam wasn’t using heroin at the start, but friends of his were, and we were 21 or 22. I came into the relationship addicted to ice. He had his own demons too, so we were using whatever we could find. His friends were using heroin and we found ourselves in the same place at the same time. Sam was like “I want to try some”, and then I’d say, “I want to try some”, and that’s just the kind of people that we were. I found, at 21, I was trying heroin and six months later I was hooked.

HM: Do you inject it the first time, smoke it?

FM: Initially I snorted it for the first six months as I was afraid of needles.

HM: What happened?

FM: I was really sick. It was too much for me. Heroin can kill you — it’s very risky to even use a small amount, but at that point I’m not thinking about all that.

HM: And the following weekend rolls around …

FM:….and I want to use it again.

HM: And you do.

FM: And I get really sick again. The first few times I got really sick, but then once the intensity wears off and it settles into your system, there’s this feeling of euphoria. So I was willing to feel violently ill, to get to that place. It masked how unhappy I was. I didn’t even realise it, but I was just trying to cover up all of my unhappiness. That’s why I used drugs. I felt like I had no direction in life and I compared myself a lot to other people. I felt like my sisters and all my friends had these dreams and jobs and I didn’t. I felt so lost and overwhelmed by life. Having drugs, and especially heroin almost allowed me to feel like I could breathe and not care so much. I’m naturally an anxious person and a perfectionist, but drugs initially helped me to relax. I always lived in so much fear — of not being enough, not making enough, never getting anywhere in life, but after I used heroin I just didn’t worry about all that stuff and would feel OK.

HM: You escaped it all?

FM: And I was like “oh my, thank god — this is how I can cope in the world — I can just use drugs.” It was so crazy when I look back on it.

HM: From the age if 17 to 29, every day you were finding something to put into your system. That’s expensive.

FM: It was very expensive.

HM: How do you fund it?

FM: There’s this image of the stereotypical drug user and addict, that doesn’t have a job, and lives on the street. That can happen, but for me, I managed to hold down a job. There are a lot of addicts working away each day that no one knows about.

HM: You were waking up, injecting, working in a coffee shop, serving people sandwiches and coffees, using at lunch time, and driving home again?

FM: Yep, I had a bachelor’s degree from Melbourne University, I was working at a coffee shop, promoting at nightclubs, working at Blockbuster Video, doing a PR internship and almost all of the time I was high. At first no one knew and the only thing that I cared about was how I would score the next hit.

HM: And 12 years of a life just disappears into the abyss …

FM: More than a decade was a wasted blur. All the years just became one, especially with heroin because my whole life was revolved around the next hit. I was working to earn money to buy drugs, and we talk about this in the 12-Step meetings. As people we are searching for some sort of purpose and direction, and my purpose and direction was to get high. It gave me a place in the world, and so I would get up, shoot up, go to work. It’s as if drugs gave me a reason to live, as sad as that sounds.

HM: So you’re onto needles by this point?

FM: After six months of snorting I decided to try and shoot up, and there was no turning back after that. I’ve got scars on my arms that are pretty much all healed — it makes me so sad thinking about it now. I used to wear long sleeves all the time because I didn’t want to show anyone my arms because I was so ashamed. I didn’t think that I’d ever be able to wear short sleeves again. When it was hot, I’d be sweating, but I was so ashamed, and I couldn’t show anyone my arms (starts crying).

HM: It’s OK …. take your time.

FM: It’s cool to sit here with you now, and to be wearing a singlet and to not be ashamed or afraid of judgment. It’s very hard to see because they’re pretty much gone, but if people see it I say: “That was a part of my journey. I’m not a bad person.”

HM: Do you think that’s the assumption?

FM: Predominantly, I’d guess. I think that’s the sad thing with addicts — there is a belief that they’re bad people. Drugs are bad, so they’re bad people. It’s not the case. They’re damaged people, and people that need help and support. They are often good people who have lost themselves but could actually lead really successful, happy lives, if they gave themselves the chance. Sure, it’s not up to other people to save us, it’s up to ourselves, but we can live amazing lives.

HM: You tried a number of times to get clean — but failed.

FM: Heaps.

HM: You realised lurching from one hit to the next wasn’t the best way to live. You were desperate to stop — why did you fail?

FM: It is so hard to rid yourself of the need to use when you are addicted. Every cell in my body was screaming, “You need to get on, you need to get on”. It was a couple of years before I realised how sad my life was, and then I wanted to stop, but just didn’t have the mental strength. What happened was, for me anyway, it slowly started affecting me at work. I needed more and more of the drug, and I couldn’t afford more and more, so I had to just use what I could afford and that became not enough. I started to feel really sick at work, cold sweats, sore throat, tired, couldn’t concentrate, started to lose friends. I disappeared, and just became really closed off from people.

HM: And I guess they give up trying to find you?

FM: Exactly, because I’m not reliable. Not returning calls, or I’m saying, “I’ll be there, I’ll be there”, and then never go. That’s what happened in the end. I became really sad, and my parents eventually found out the extent of my drug use, because I hid it really well, and they gave me a 12-Step book to go to a meeting. That was the first time I’d ever heard about how people like me could live clean and happy lives.

HM: Were you thinking you could get clean?

FM: I didn’t know any other people in my immediate circle, other than my partner and a couple of friends, that used drugs like we used drugs. I thought that we were a different kettle of fish — real no-hopers, but I went to a meeting and when I left I was filled with this hope, that maybe there was a way out as others had got out.

HM: It wasn’t easy?

FM: It was hell. It took almost four years of trying and failing. I went to rehab, then the day I got out I relapsed — the first day out! My partner went to a couple of rehabs too, and we kept relapsing, then someone said “Fen, why don’t you try long term rehab?”, which was 10 months. After I left there I still relapsed!

HM: When you’re doing a 10-month rehab, are you closed off from the world?

FM: Completely closed off, so no phone, no internet, just with a bunch of other alcoholics and addicts, in a little community. It was a therapeutic community, and I guess you’re completely closed off, but what happens is you’re surrounded by other addicts, and other people that have got similar mannerisms to you. People finish their program and relapse, and you’re still in touch with these people. That’s what happened with me. I was still in touch with people that left the program, relapsed, and then I just thought, you know what, I’m just going to have one more.

HM: After 10 months of being clean.

FM: Can you believe it? It took me a few months to get off all the medication — I don’t call myself ‘clean’ or ‘sober’ until I’m off everything. I came off the medication slowly, got six and a half months of clean time up, off everything, not a thing in my system, and then I thought, you know what, I’m sneakily going to shoot up heroin, once. This is the addict’s mind, thinking it’s no big deal. I’m just going to have it once and that’s all I need, just one hit. I wanted to feel that feeling, and then that’s it … I spiralled out of control. Two days later I had it again, the next day I had it again and then bang, I was hooked. Every day.

HM: Your parents are aware at this point. Are you now being honest with them, or is it constant lies?

FM: I’m pretty much being honest with them, but sometimes it can take a little while, because of all the shame I carried. I thought using meant I wasn’t a strong human; I’m so weak, the self-pity. “Fen you’re so weak, how could you do this again. You’re a bad person, you have let everyone down again”. That feeds the thinking into, “oh, I’ll have another one cause I’ll never amount to anything and it’s all just too hard. You’re such a failure”.

HM: How do you get the strength to say no to yourself?

FM: Working with psychologists and other addicts helped me. They believed in me when I couldn’t and helped me to shift my thinking that I’m not a bad, worthless person. They helped me believe that although I’ve made mistakes, it’s OK. “You’ve used, that’s OK. You’ve slipped up, but you can pick yourself back up and get clean again”. I went to these meetings for three and a half years, relapsing. I’d go to a meeting and I’m one day clean, “Hey, I’m Fen. I’m an addict and I’m one day clean” and then I’d use that night. I’d go back the next morning “Hey, I’m Fen. I’m an addict and I’m one day clean”. People would all clap, and I’d feel so much shame, but I also slowly built up my self-esteem. Having others who understood encourage me to keep trying was important.

HM: But you’re turning up, trying to get it right.

FM: Exactly. I’d get 60 days up and then I’d use again. I found it really hard, but I never gave up trying.

HM: Tell me, you get to 60 days … What is it on day 60 that’s different from 59?

FM: In those early days it takes a lot of recovery of your thinking to get to a place where you have freedom from the obsession to want to use drugs. In those 59 days I’m still so obsessed and I’m holding on for dear life. I’m trying to do this for Sam, I’m trying to do this for my family, I’m trying to do this for me. It’s really hard, but I keep fronting up, and then on day 60, maybe something really small happens. Maybe I slam my finger in the car door, and I think “f--- it, I can’t do this”. Maybe it’s these small little things that are building up, and for whatever reason I guess I’m not being honest about some things. I’m holding things to myself, and maybe I’m trying to still do this for everyone else because I don’t believe in myself yet. I’m not desperate enough to completely change and let go of that life, then on day 60 I use again.

HM: What changed everything?

FM: Losing a baby. I became pregnant with Sam, which I didn’t realise, and I was still slipping up and using. I was nine weeks pregnant and I didn’t know. I used heroin, because that’s what I always did, and then I had these stomach pains four days later. I ended up in Epworth Hospital, and the lady said, “You’re having a miscarriage”. It was the first time I’d ever been pregnant, and I also lost a friend who was an addict all in the space of one week. Those two things finally got me over the edge. I didn’t realise at the time it was those two things, but they were the turning point for me.

HM: That was Mother’s Day, 2015.

FM: It was on May the 14th, the day after my Dad’s birthday. Two deaths were what it came down to in order to get me to stop. It was hard, more so in the early days, for the first year, that was the hardest, but for some reason after losing a baby and a friend dying, there was a strength to say “no”. I didn’t want to hurt myself or my family anymore. There would be times when I just wasn’t feeling excited about life, and I was still really vulnerable and really scared of the world, thinking it was all too hard. I just want to use one more time.

HM: How did you avoid it?

FM: For me, go to a meeting, tell my friends in recovery, learn to open up and cry. I think that’s important. Learning not to be afraid of feeling things. Both good and bad. Say, “Hey I’m struggling, and I need some support”.

HM: So they could protect you, and remove you from dangerous situations?

FM: Yeah. You realise that in order to change that pattern, that behaviour, you actually need to do something. You have to put some action in place. So I would tell my friends, I’d call one up and say “I’m so sad, I’m just wanting to use”. Hopefully you’ve got a friend that will come over and keep you occupied for a few hours while that feeling is there, and you just want to go do it. Then it passes. You go to bed that night and you think “I made it through today”. Then tomorrow’s a better day, and you might not get that feeling for another couple of months, then you do the same thing. When you are in addiction, to get one day clean is so amazing. It really is a struggle.

HM: It’s a long, hard haul.

FM: Exactly, and there’s no magic recipe to tell anyone that this is exactly what you need to do to get off drugs and stay off drugs. It is a long process, and it can take a lot of relapsing. Some people may relapse once, some people may never relapse; it may take 10 or 15 goes before they get to a place where that’s it.

HM: Are you confident now that you can stay clean?

FM: I’m really confident. What comes up for me now is wanting to have a drink sometimes, which might lead me to be vulnerable. Wanting to drink happens when I get anxious. I think it’s quite common, you get anxious, and even coming today to speak to you I get this anxiety, but it’s about getting through that and realising that I don’t need to have a drink. I can just be anxious and that’s OK. I can feel a bit of anxiety, my heart can race a little bit and I can just breathe and be OK, and have a really good time without alcohol or drugs. I can wake up in the morning and be really present and available to my baby. I can go and do my exercise which I love doing, and I don’t need to have a substance. I don’t need to have a drink, or anything.

HM: What’s the hardest part about staying clean?

FM: Facing things that I find scary in life without trying to mask it. When I am putting myself out there, studying psychology, going to a new uni, I find that really scary. It would be great to have a drink at the end of the day, or just have something at the end of the day. Really, now I’m at a place where life is so amazing that I’m excited about being really present and not having substances. Most days, I don’t even think about wanting to use something, but when I do, I’m able to think about all I would be jeopardising and I can get through.

HM: How often did you at the start?

FM: The first year I thought about using most days, and then the second year I guess it let up a little bit. I focused my attention elsewhere, and I found things that really excited me. Exercise for me gives me that endorphin hit now.

HM: You’ve became an addict to exercise?

FM: Pretty much — it’s a healthy addiction, though! It doesn’t make me sick, and it doesn’t keep me isolated, in fact it’s the opposite. I meet communities of people, and I become really social in that aspect and it makes me really happy. I was searching for this happiness, connection to others and this feeling of being content with myself, and that’s what training has given me. I don’t need the drugs anymore; drugs don’t serve me at all. They don’t do anything for me, so why would I use them? I have had this complete shift in perspective, and shift in thinking, where it’s like “sure, I used to shoot up a few times a day for years, but I don’t want to do that anymore”. That’s a cool message to say, because you think that isn’t possible when you’re in it. How is this obsession to want to use every day ever going to leave me? But it can.

HM: And has?

FM: And it has! I just bought this Magimix food processor, and I’m so excited about it! It sounds pretty lame but I feel really excited to make things in this food processor, and that’s a feeling that I guess drugs used to give me. This excitement, but it’s changed to other things. It’s beautiful to be excited about really small things in life that I never felt when I was younger. When I was using, I just felt numb. I wasn’t able to feel happy about small things.

HM: Almost 33, 12 years using. When you think about that, and you think about that 12 years, what is your immediate thought? Do you think, what a waste?

FM: I feel like it’s really lucky that I am alive, because I didn’t think I would be, and back then I didn’t really care, to be honest. The only reason I would have wanted to stay alive was for my parents. I didn’t want to do it for myself, so I think it’s really lucky that I’m alive. I do think sometimes about all the things I could have done had I not gone down that path, but then I think “you know what, it is what it is”. There’s no point reflecting on the ‘what if’ side of things, because in a way, it’s given me the life I have today, and I wouldn’t change this life for a single thing. I feel like I’ve got a lot of compassion for what I’ve been through, and I relate to people that have gone through hardships. I have so much respect for people that have been through hard times and get through it. It’s allowed me to meet people that I never would have met before, and maybe I can help people. That’s really cool. Maybe all of it has been worthwhile, because now I can help someone else stay clean.

HM: You’re a mum now. Your parents had a child at 17 that became an addict. Can you imagine Mickey in 15 years’ time being an addict, as a parent?

FM: I can’t even imagine it. It is a horrific thought. I pray it doesn’t happen — as my parents probably did.

HM: Is there anything we can do as parents to try and avoid it?

FM: There is no complete preventive, but one thing that I will do with Mickey is be a really open book and let him come to me with everything and anything. I don’t want to judge him for anything, and I don’t want him to be scared to come to me for whatever reason. I want him to say, “Mum, friends of mine at school have got weed and I really want to try it”. I’d want to educate him as much as I can about drugs, and although it’s hard, I don’t want to control his life, just educate him as much as I can and be as open as I can, and as loving as I can. It’s not to say I wasn’t loved as a little one, but I don’t necessarily think I felt completely understood. I was scared to go to my parents about things, and I wish I would have been a little bit more open. Maybe it’s about me going to Mickey and saying, “Right, now we’re going to sit down and talk about this. I want you to ask me any questions that you want, and I will do my best to answer honestly” — and just go about it that way. We can’t live in fear about what they’re going to do, because we can’t completely control them. We have to be there for them if they make the wrong decision.

HM: You said earlier you felt like your life wasn’t as valuable as others’, that you were hopeless and that you were almost loathing yourself. When you sit here now, how do you feel about yourself?

FM: I feel really good about myself, and I like I can say that. I feel like I’ve achieved lots of things, and I feel like I really try and look after myself. I try and eat as healthy as I can, I exercise as much as I can, I’m an awesome mum, and I’m a really good friend. If I say that I’m going to do something, I do it. I don’t judge other people for what they do; if they make mistakes, they make mistakes; that’s fine. I feel a lot freer, and at ease with myself and others. I don’t think I’m a really shit person, I don’t think I’m a really good person, I just think I’m an everyday person, and that’s cool! I’m not trying to be really famous and amazing, and I’m not trying to be really scared and isolated, I’m just trying to be a normal person. I think that’s really cool, so I’m proud of myself!

HM: As you should be. What does the future look like for you?

FM: I want more babies, and I’m hoping to be a psychologist. I’d love to move to Byron Bay and have a really low key, chilled out life with a veggie garden and kids in bare feet, working a couple days of the week.

HM: That’s a long way from where you’ve been. I’m always blown away speaking to you. I love the fact that you are so open. Thank you for talking again, and well done on staying clean.

FM: Exactly. I just want to be healthy and happy. Thank you for having me, Hame.