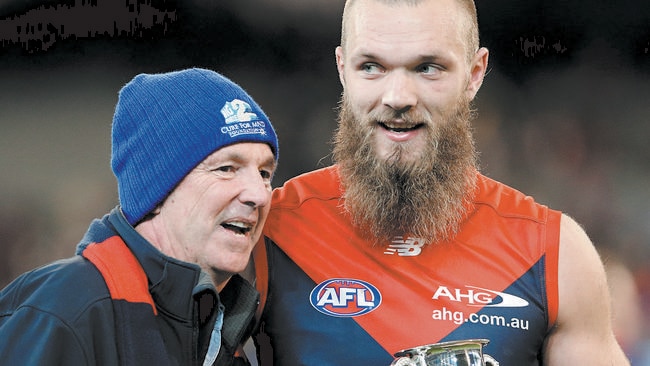

Hamish McLachlan chats with Neale Daniher about his battle with motor neuron disease

HAMISH McLachlan chats with Neale Daniher about his battle with motor neuron disease and how he won’t allow the disease to take away his optimism and dignity.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I’VE been fortunate enough to have spent a little time with Neale Daniher in the last year or two. Sometimes alone.

Sometimes with just a handful of people in a commentary box, as we waited for Neale to speak bravely to the viewers, all of us wanting to somehow rid him of the hell he is enduring.

Once it was with a couple of other MND sufferers and their partners, all of us in tears, not saying too much at all.

And twice on the Queen’s Birthday Monday, I have stood alongside him, seeing him smile and hearing him laugh in front of 75,000 at the MCG.

In fact, his laugh, and his smile, is how I will always remember the Big Freeze at the G.

The sound of his laugh will never leave me. In the small amount of time I’ve spent with Neale, something has become very clear to me: if I was told I only had a few years to live, I know I couldn’t be as brave, or courageous, or selfless, or inclusive, or good humoured, or inspiring as Neale Daniher has been. He has set a new benchmark on how to deal with adversity.

We spoke over a cup of tea and carrot cake, just before the Big Freeze this year.

HM: Christmas time, 2012 — that’s when you first noticed things weren’t right?

ND: Yeah, Hame, it was towards the end of 2012, and I was noticing some weakness in my hand, and I was struggling to hang things out on the washing line. I had a beer with my farming mate Cam Taylor in Tambellup at Christmas time, and he shook my hand and noticed that it was weak. It was quite perceptive of him. That was the first time that anyone outside of the family picked up on it.

HM: Had you talked to anyone in the family about what you were feeling?

ND: I might have said to Jan (Neale’s wife) that things weren’t quite right, but just in passing.

HM: Had you seen a doctor at this point?

ND: No.

HM: So your mate Cam, who was perceptive and knew that the Danihers shake a hand firmly, picked up on it?

ND: Yep, he said: “What’s happened to the old grip — lost a bit of its grunt!”

HM: That comment, and the trouble with the pegs on the line, was the catalyst to go and see someone?

ND: Yes. At the time I was working at West Coast, and we had great doctors and physios there, so I went and saw them. They thought it might have been just a bit of a nerve block, which I was hoping for as well. After that, we went on the journey to find out what it was.

HM: Yours was quite a quick diagnosis — it took just six months. Is it true that your doctor said to you, “I don’t know what it is yet, I just hope that it’s not MND”?

ND: He didn’t say it directly to me, but he said it to someone, and it eventually got back to me. They were saying: “We hope it’s something we can sort out, something we can manage and treat. hopefully it’s not MND.” I only heard that after.

HM: It is unbelievable that you test and pray for something else — anything else — except MND.

ND: That’s how they diagnose now. They diagnose for everything else until they run out of things that it could be. There is no specific test for MND. If there’s nothing left they can test you on, unfortunately, you are diagnosed with MND.

HM: When were you told you had MND?

ND: It wasn’t my doctor who told me; it just gets sent down the line to another specialist and another specialist. I ended up in Melbourne for a second “third opinion”. There was a lot of “It could be MND, but we want to do another test”, until eventually someone you don’t know tells you, “Here are the results, sorry, but you’ve got MND”.

HM: Were you by yourself when you found out?

ND: Yes, I was in Melbourne at the time, no one with me.

HM: You would have known a bit about MND by that point, I imagine. From being told those horrific words, what happens to you, mentally?

ND: I walked out of the doctor’s offices, and got a cab to Tullamarine, to catch a plane back to Perth. It was like a ton of bricks had fallen on me, like a huge weight, the thought of “you are about to die” and nothing else suddenly seems too important. You have this thought that is just constantly sitting there — that you have about 2½ years left to live. It’s like: “Bugger! It’s not something else — it IS MND.” It felt like a big tidal wave coming over me. It’s fairly typical of the grief cycle, Hamish, first to go into disbelief, denial and “why me?”.

HM: How long does the disbelief last?

ND: (laughs) Not too long! You do think, “Have they mucked up the diagnosis? Maybe they have mucked it up, I hope they have!” but sadly, that disappears pretty quickly. There is anger on top of the disbelief. I remember thinking to myself: “Wow, it’s me, not someone else, I have MND. F---, I’m going to die!”.

HM: How do you approach that realisation with your wife and four kids?

ND: I have two daughters in Melbourne, and two sons in Perth living with me and Jan. I talked to my two sons, and rang my two daughters here in Melbourne. With my 10 brothers and sisters I just thought, “I’ll send em’ a text!” A lot of friends said they didn’t know how to respond, so I just told them to “play on” and get on with their days.

HM: I heard you gave yourself a coach’s address on the way back to Perth?

ND: I just use the football term “play on”. That helped me as much as them, I think — let’s all “play on” and keep chasing the ball and doing what we all have to do. I remember I was halfway through the flight back to Perth after receiving the final diagnosis, and I was moping about and whinging and I would have kicked the cat if there was one on board, and I just said to myself: “OK Neale, you’ve dropped your head for the last few hours, you’ve been carrying on and dropped your bottom lip — how is that working out for you then?’’.

HM: You gave yourself a serve mid-flight?

ND: I had to —

I wasn’t going to achieve much moping about. It

was the moment I realised I had to get on with a few things rather than stare at the wall!

HM: Christ — you didn’t give yourself too much time to wallow. You probably didn’t even get over Bordertown!

ND: Dry farming country around Bordertown!

HM: It is; tough summers, I imagine! I assume the way you deal with it, as you just did then, and the way you treat it, directly correlates to your family’s ability to cope and deal with the dire scenario.

ND: You have the choice to laugh or cry about it, and laughing is a lot more fun. Day to day I have been very lucky: the downward progression of the disease hasn’t been as quick as others. I think to your point, though, if you are able to manage it yourself, it’s a lot easier for those around you to manage as well.

HM: So, diagnosed in mid-2013.

At that point, was it still just your hands that were affected?

ND: It was.

HM: And since then?

ND: It’s all upper body that’s been affected since.

HM: All cases seem to be different?

ND: I’m no expert, and I haven’t really explored it, but yes, initial symptoms can appear anywhere, hands, feet, speech — none of them are any bloody good, though! Some people want to Google it and find out everything about it, but I’m the opposite. Obsessing about it doesn’t help me, so I don’t do it. The disease is progressive ... it never plateaus. I used to be able to do 50 push-ups at 52 years of age, and now I can’t do one. I used to be able to swim 2km, and now I can’t do 25m. I used to be able to do up my shoelaces and my buttons, and now I can’t. The shadow that MND casts hasn’t spread to my legs yet — I can walk. So I’m very grateful. It all ends the same, unfortunately: unable to walk, to move, to speak, to swallow, and then to breathe … but progression varies from one person to the next.

HM: Is tomorrow noticeably worse than today in terms of your body’s decline?

ND: It is, but it’s more measured in months for me. I won’t wake up tomorrow and say, “Gee, I’m worse than yesterday”, but I will notice the difference in a few weeks.

HM: I’m pleasantly surprised at how little difference there is — outwardly, at least — from this time last year to now.

ND: (laughs) You haven’t seen me try and eat soup!

HM: I’ll grab a bib! Many sufferers say they have never been sharper mentally because they use their minds.

ND: You have to be careful with where your mind takes you. As you physically fade, people say it can take your dignity, but it can’t if you don’t let it. You’ve got to make sure to think optimistically. Each day offers opportunities even while you’re sliding down the hill. Your mind can be sharp, but it can still take you to dark places. You have to be aware of that and pull it back, and keep your thinking away from where the disease wants to take you, to those dark and hopeless places. It’s not just the physical battle; it’s also the mental battle.

HM: It’s a rude bastard of a thing!

ND: It takes away everything it can — it even tries to take away your dignity. It tries to!

HM: It shows you no respect, so we need to show it some respect if we are going to beat it. we can’t pay it so little attention.

ND: I call it “The Beast”. What we’ve been able to do is put a light on it. It’s been hiding away in the cave, killing people, but we’ve put a light on it, and raised awareness. We’ve made people aware that we’re woefully underfunded to take this beast on. Part of this awareness campaign is to appeal to people to help us find a treatment, and a cure. Neurologists say worldwide that if there is going to be a breakthrough in neurological diseases — whether it be MND, Parkinson’s, MS or dementia — the breakthrough will be with MND. They think they can crack the code before the others. What The Big Freeze did last year was raise close to $2.5 million, and on the back of that, we’ve had some really encouraging advances. There has been a compound identified and discovered here in Melbourne, which when applied to mice with MND freezes it and stops it. It gives us hope. Hope! It’s a big jump from that to humans, but they have found something. We have hope, Hame, hope!

HM: Hope and MND have never been spoken of together.

ND: They haven’t. Our Big Freeze campaign was taking something that was hopeless in 2012, to something that is now hopeful. I’m not good at giving up. A boxing analogy, Hame: MND has never been beaten, and it’s over in that corner knocking the sh — out of us. In our corner, we’ve got the “Freeze Army” and while we mightn’t be able to knock it out yet, we at least are throwing punches, and in time we will nail MND. We will just keep “jabbing” away, until one day, the ref holds our hands up!

HM: It’ll be a popular win! Has naming MND “The Beast” helped you?

ND: I think it allows me to personalise it. I’m trying to keep my message simple and keep it non-medical. Personally, naming it helps me because I want to personalise it, give it a name, to visualise it in my head.

HM: What does it look like to you?

ND: Big, hairy, ugly and dark. A cross between a blowfly and moth; an ugly piece of gear, mate.

HM: The foundation was ostensibly Ian Davis, Pat Cunningham and yourself. I heard you once say it’s not a very sustainable board.

ND: We are the “Three Musketeers”, but unfortunately it’s not sustainable. Ian has MND, so do I, and Pat is working very hard with his wife, Ange, who has MND. We need to put longer-term plans in order and we are. One of our core values is urgency and I assume you know why.

HM: The “Big Freeze” — where does the name come from?

ND: From the Ice Bucket Challenge, which was a campaign that went worldwide. The Big Freeze was a spin-off from that, and it was around stopping the progress of MND. We want to stop it moving, so then we can work on a cure. You can’t cure it until you can treat it, and treatment is about slowing it down. That’s where “The Big Freeze” came from — freeze The Beast!

HM: No effective treatment, no cure. They are five words that just shouldn’t go together.

ND: And until the Freeze Army got involved, “no funding”. Add them on and there are seven words that don’t sit too bloody well.

HM: There is no leakage with the Cure for MND Foundation on admin or marketing. Where does the money go?

ND: Every cent donated by the public within The Big Freeze campaigns goes directly to research into developing treatments and pursuing a cure. From the $2.5 million donated last year in our first Big Freeze, we spent $1.75 million on helping fund the best and brightest MND researchers across Australia to do their work. We are proud to say that with those funds, our researchers have made discoveries and advances that have brought us closer to a better understanding of what makes The Beast tick. We have then spent another $1 million in helping fund two clinical trials of potential new therapies for Australian patients that will start enrolling patients very soon. That’s real hope where previously there was none, and real hope that wouldn’t have been possible without the generosity of the Freeze Army. Beyond the 2015 Big Freeze, the foundation is now looking to undertake a new initiative: establishing a MND therapy development pipeline whereby we will look to fund the development of promising new compounds through the lab and, for the first time, into clinical trials right here in Australia. Clinical trials are the only way we are going to solve this, and until now there hasn’t been any. Pharmaceuticals won’t invest in it because there are only 2000 people in the country with MND, and they can’t get rich from that! We want to create a tablet, and do trials in Australia. Our whole focus is Australian trials, for Australians, by Australians. That is what we are about. That is where we will crack the code. We have strategically gone to the community in Freeze 1; we’ve gone to the community with Freeze 2 as well, but after the credibility of the first Freeze, we also went to the government. We went to them and said: “Support us and partner with us, and go dollar for dollar with us to fund medical clinical trials in Australia.”

HM: What do you think the number you need is?

ND: We’ve got a clear plan around developing a cure and the strategy which requires $40 million over four years. We’ve identified a major barrier to research discoveries reaching patients. We need a focus on clinical trials and infrastructure, and we need to bring together a dream team to deliver it. We want every single patient diagnosed with MND in the future to have the opportunity to have access to a clinical trial here in Australia. We want the government to back us and financially partner us in our endeavours.

HM: What do you hope the project can achieve?

ND: We know it’s a big ask, and a big undertaking, but we are prepared to do it. We plan to fund the development of a minimum of 10 new drug treatments in the laboratory, hoping one or more of them is a game changer. Those that look promising in the lab, we will then help fund through into clinical trials right here in our own back yard, in Australia’s leading MND clinics around the country that we have aligned with under our Cure for MND Trials Consortium. We are looking to stock the medicine cupboard, where previously there was only a bare shelf. The researchers and neurologist are ready to go — we just need the funding.

HM: The Big Freeze is one initiative. Another is the Daniher Drive — what is it?

ND: The Daniher Drive is a four-day car drive through rural Victoria. It’s about having fun, raising awareness and an opportunity to raise much-needed funds for what we’ve been talking about. That’s purely what it is. We’re going to drive around Victoria and try and raise over one million bucks. Last year we went down the Great Ocean Road to Warrnambool, over the Grampians, up to Bendigo and then Albury. This October, we going out of the city to Mansfield, through the Man from Snowy River country, up to Hotham, and back via the Gippsland Lakes and Sale. There’s going to be a community cricket game and sports night in Sale, and a rock ‘n’ roll band night at San Remo. If you’re out that way, we are coming to see you to raise awareness of MND, and funds, to beat The Beast.

HM: Who runs it all?

ND: Myself, family and an incredible group of volunteers. Our Drive committee is led by Penny Collins, who, like all our volunteers, is so generous.

HM: What has been your biggest challenge, not physically, but mentally? What was your worst day?

ND: The worst day was the day that I was finally diagnosed. But trying to find a cure for MND has given me something to focus on and be positive about. An opportunity. The old Chinese proverb: “Every crisis creates an opportunity”. We can do some good, it might not help me, the cure may not occur in my time, but if we have played a small role in bringing an end to The Beast, then it’s been worth it. If someone says in five years’ time, “You’ve got MND but there is hope for you, take these tablets”, then that is a huge improvement on: “Sorry, there is simply nothing we can do”.

HM: Your football legacy is significant, but this is what many Australians will remember you for.

ND: Maybe; however, I always say I would rather not be doing this though! I would rather not have MND! It’s a classic example of situational leadership — the ship is going down, so you better start paddling. I’m not big on legacies, but if I leave even a little one, it means we have made some noise and hopefully done some good for those future MND sufferers. The satisfaction will come when someone in a white coat says: “We’ve got a cure”. We’ve ploughed the ground and now we are beginning to see some green shoots.

HM: You’ve heard a lot of stories and met so many people along the way. Is there one moment that has touched you more than others?

ND: The Big Freeze support has been overwhelming — that blew me away. The march to the MCG with the Freeze Army is an outstanding feeling.

HM: In year one, you were thinking that raising a couple hundred thousand would be a monumental effort, yet you raised $2.5 million.

ND: We have received tremendous support from all the broadcasters; in particular Channel 7 and the Sunday Herald Sun and Herald Sun have really exponentially allowed us to get our message out to a far broader audience. Without that, we wouldn’t have been able to do what we have done. The whole Big Freeze experience was overwhelming. It was on live TV and we didn’t know what to expect — people could just switch off or go to another room. It was only after the event that we knew how much support we received and what had happened on the other side of the TV screen.

HM: It was like It’s A Knockout, but for a cause. I’ve heard you say: “I don’t waste my time drinking sh — red wine anymore”. Is there anything else you don’t have time for now?

ND: When you have a terminal disease, it’s very easy to stop striving. Now I tend to sit back from it all and wonder what the striving is all about. That can happen with MND. Everything I do now, with generous, like-minded people, is less ego driven, and I try and make a difference while having some fun. And I notice things more — like the changing seasons and the birds chirping. Nothing phases me too much anymore, I can tell you!

HM: It’s a horrible disease, but you are doing an extraordinary job raising awareness and funds, and you’re making people smile while you do it. You’ve taught us all a great deal.

ND: Thanks Hame, but it’s never one person. I have tremendous support from my family, Ian Davis, Pat Cunningham, who is just a genuine champion of a fella, Bill Guest, Lewis Martin, James Garland and close friends who act voluntarily and ask for nothing in return. Right now, I have to accept that I have got MND, but I don’t have to accept that it is hopeless.

HM: It’s not hopeless anymore, thanks to you and others. Thanks for talking.

ND: Pleasure, mate — nice to have a good cuppa and a chat.

To donate to Cure for MND and try to beat The Beast go to curemnd.org.au