Before the tourist buses that ferry 6.2m visitors a year along the Great Ocean Rd it was a ramshackle, muddy track. Here are incredible facts you didn’t know about one of the world’s great scenic drives.

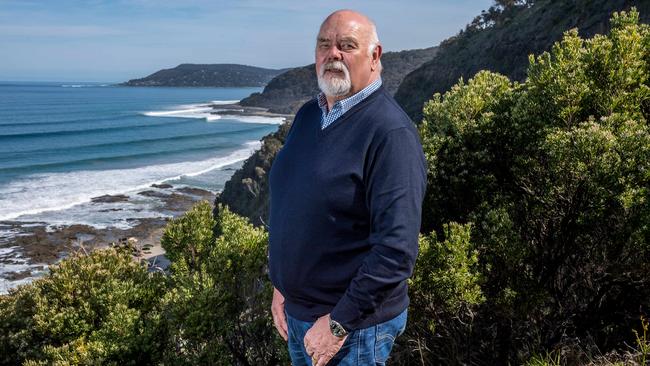

Roy Moriarty could play footy on the Great Ocean Rd as a kid.

Aside from the two-week summer peak, the route that streaks along the Wye River foreshore saw more kick-to-kick than coaches.

It was before the 243km road became one of the world’s premier tourist destinations, and dozens of buses rumbled through town each day.

“We could nearly still play football on the road here apart from the two weeks over Christmas,” he said.

“Now there are cars coming through all the time. There is not a day that you probably don’t see 20 buses come through, and sometimes probably up to 60 buses.”

The 62-year-old — a school bus driver who captained the fire brigade through 2015’s devastating Christmas Day fires — moved to the seaside hamlet as a six-year-old after his parents and grandparents bought the general store.

The Moriarty clan counted for eight of Wye River’s 17 residents then.

There was no electricity and the town’s phones ran through a switchboard at the store’s post office.

Even now, Wye River does not have water or sewerage but the population has quadrupled.

It has grown alongside other towns dotted along the road, “a national highway” on which construction started 100 years ago on Thursday, September 19.

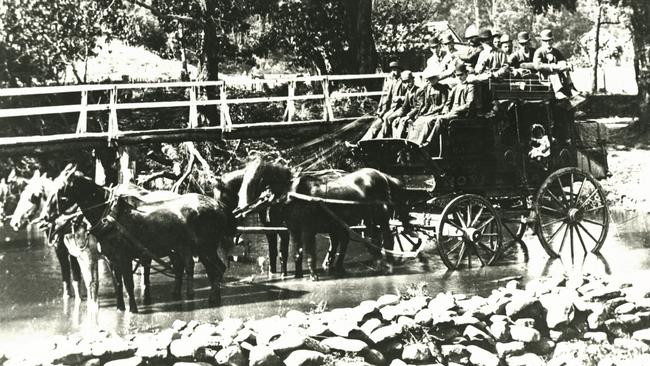

Archive footage shows the road being chiselled in seaside cliffs, and horse and carts clambering over rocky track and straight through the Erskine River.

It was three years after construction began that the road between Aireys Inlet and Lorne was opened, and another decade before the full Great Ocean Rd was complete.

Now, the “engineering marvel” lures 6.2 million visitors each year — more than Uluru and the Great Barrier Reef combined — and they collectively spend $1.7 billion.

“It’s a mecca,” Vicki Phillipp, a tour guide at Split Point Lighthouse, said.

The lighthouse, made famous by Australian TV show Round the Twist, has stood on the cliffs at Aireys Inlet since before the Great Ocean Rd was built.

It has been a beacon for boats navigating the treacherous Shipwreck Coast since 1891, and more recently a beacon for tourists who make it their first stop on the drive from Melbourne to the Twelve Apostles.

Korean food trader Ryan Kim, 31, booked just a week’s holiday in Australia but dedicated a day to touring the Great Ocean Rd.

He and three friends rotated drivers as they wound their way down the road this week.

“It is really beautiful,” he said, despite lamenting the five-hour-plus roundtrip.

“We can’t see these things in Asia — especially in Korea, there is just nothing like this.”

The chance to spot a wild koala or kangaroo also drew Sri Lankan travellers, Rozana Daniel, Raj Kumar and Taniya and Makesh Wanigasekara.

The Wanigasekaras had seen the tourist route advertised online, and weren’t disappointed when presented with the real thing.

“It gives us a great opportunity to see the whole area,” Ms Wanigasekara said.

“We love it.”

They were among the couples, families and groups of friends who on Wednesday descended on the Great Ocean Rd’s “gateway” — a Memorial Arch built at Eastern View as a monument to the servicemen who constructed the stretch of road to Cape Patton.

Few who visit know that the road was built on the backs of veterans returning from World War I, according to local historian Peter Spring.

About 3000 servicemen used picks and shovels to carve out what is arguably the road’s most difficult section.

But the names of just 400-odd are known, the remaining 2600 lost along with historical records.

A documentary marking the centenary of construction, The Story of the Road, is piecing together their stories.

“A lot of people will pull in for the view or to take a photo without having a sense of how this engineering marvel took place,” Mr Spring, a member of the Lorne Historical Society, said.

“From the ridgeline, the servicemen would lower themselves over and down the cliff with a rope around their waist.

“At the grade level line, they would dig themselves a couple of footholds and then basically start digging into the cliff.

“It was all done with pick and shovel. In those days, so many of the return servicemen were shell-shocked by the war that they couldn’t really use explosives.”

The diggers camped along the road in places like Grassy Creek and St George River, and named key points after the war they had just endured.

Near Big Hill, Somme is an area reminiscent of the muddy French battlefield that recorded one of the bloodiest military encounters of WWI.

Sausage Gully and Shrapnel Gully, not far from the Cape Patton lookout, pay homage to Gallipoli’s Anzac Cove.

“The road itself is the memorial to the servicemen,” Mr Spring said.

“You’ve got 3000 men who have been in the worst conditions imaginable in WWI and then they came back and tackled this incredible project.

“It is the sheer doggedness of those soldiers that made that road.”

Great Ocean Rd communities have also shown a dogged determination to recover from natural disasters — first, fire and then landslides — that have hit in recent years.

Bushfires raged along tourist route for almost a week before turning on Wye River on Christmas Day in 2015.

The flames destroyed more than 100 homes there and in neighbouring Separation Creek — two communities still recovering.

“Considering nobody lost their life, it has taken us a long time to heal and I think we’re still healing,” Mr Moriarty said.

The then-brigade captain sent a text on Christmas Eve, rally the troops for what would like come over the hill the following day.

The brigade had about 20 firefighters on the books — many who were out of town — but eight replied and 12 turned up to fight the following day.

Less than a year later, parts of the Great Ocean Rd were closed after the wettest September in a century sparked a series of landslides.

Since, technology used to predict earthquakes in New Zealand has been rolled out and kilometres of rock netting installed.

It is part of a massive maintenance blitz to upgrade the road, as it copes with the “enormous stress” of increased tourism.

Camperdown’s Dom Mitchell, who has directed traffic on-and-off for two years amid the construction, marvelled at the road’s original builders.

“I don’t know how they did it,” he told the Herald Sun while holding a stop-slow sign and cautioning the driver of a Toyota 4WD who had failed to tap the brake.

“You just have to look at some of the stuff they dug out with picks and shovels and crowbars.

“The equipment we have now is brilliant.”

Some have lambasted the tourism boom for contributing to overdevelopment and overcrowding, and creating traffic snarls along the popular road.

Speeds on a section of the Great Ocean Rd were even dropped to just 20km/h earlier this year to cope with an influx of visitors during Chinese New Year.

But the growth is a “good thing”, Great Ocean Road Regional Tourism chairman Wayne Kayler-Thomson said.

The group is eyeing ways to attract tourists to stay longer, spend more and spread further across the region.

He said smart investment in sustainable project would be key, with a $1.5 billion pipeline of projects promised, planned or approved since 2015.

These include road maintenance, an overhaul of the Shipwreck Coast and attractions such as the proposed $150 million Eden eco-resort at Anglesea.

READ MORE:

“The Great Ocean Rd is genuinely an Australian tourism icon,” Mr Kayler-Thomson said.

“It is an amazing achievement. You would not achieve that today.

“We should consider the legacy that has been left for us and ask what the current generation and future generation are going to do to build on that.”

‘Angels’: Hero Coles workers save mum’s life

A mother of three has opened up on how her life was saved after she suddenly collapsed while doing a routine supermarket shop.

Wildlife and traffic fears over music festival

Wildlife advocates fear a weekend music festival in central Victoria will endanger native animals including rescued joeys.