Melbourne’s Max Gawn is a giving interview subject. Sometimes, he gives too much.

Earlier this year, he spoke of a Demons club “curse” which dates to 1965 and a crazy moment in Melbourne’s footballing history.

Some, such as Gawn and club legend Ron Barassi, tend to believe that one rash decision then might explain the Demons’ pattern of misfortune in the 55 years since.

What else accounts for the key moments of Melbourne’s modern history, which play like a highlights reel in woe? The defeats from the jaws of victory. The worst of choices in the worst of moments, in scenes so unlikely that they invite notions of supernatural intervention.

That’s the power of a so-called sporting curse. It doesn’t follow laws of logic. It sweeps away the vagaries of luck, endeavour and excellence. And so the curse grows, year by year, as a malignancy which feeds on failure and becomes the coverall explanation for the inexplicable.

When success is within reach, as with Melbourne after a superlative season, the sporting curse emerges from the shadows, to maraud and taunt. It can assume a legitimacy at odds with more conventional measures, such as tackles and hard ball gets. Think of a little green man on your shoulder, whispering sweet doubts in his fight for survival.

Melbourne is now rebadged as the team that can. There is a physicality in its play, a poise through the midfield, which has long been considered foreign to Melbourne.

There is a team-over-individual dynamic which hasn’t featured at the club since the early days of the Berlin Wall. There is a belief, too, which has not flowed since JFK was president.

Gawn channelled the giddiness of the club’s resurgence in round six, moments after Melbourne had bullied, almost toyed with, last year’s premier, Richmond.

He referred to 1965, when pubs closed at 6pm and a six-pack cost less than a pound. Call it Gawn’s Voldemort moment. He spoke of Demon demons which might have been better left unsaid. Gawn mentioned the war.

“That’s where the Norm Smith Curse started, but I am not allowed to say that.”

Gawn grasped that he had just summoned a club ghost which has haunted Melbourne fans since their grandparents were learning to read.

“Let’s just pretend I didn’t say Norm Smith,” he added.

It was too late. The “Curse of Norm Smith” may not have the everyday currency of the Colliwobbles, which needs no explaining, or the latter day Kennett Curse, when the Hawthorn club president declared Geelong could not win big games and appeared to trigger Geelong’s subsequent 11-match winning streak against Hawthorn.

But the curse gets resurrected whenever the Demons play well. It is destined to be whispered about and feared until the day which has not yet arrived — a flag.

Only then can the ghost can be dispatched as a figment of fevered disappointment.

HOW THE DEMONS’ ‘CURSE’ STARTED

This curse starts with the most unlikely sacking in football history.

There is good reason that the best player afield in a grand final wins the Norm Smith Medal.

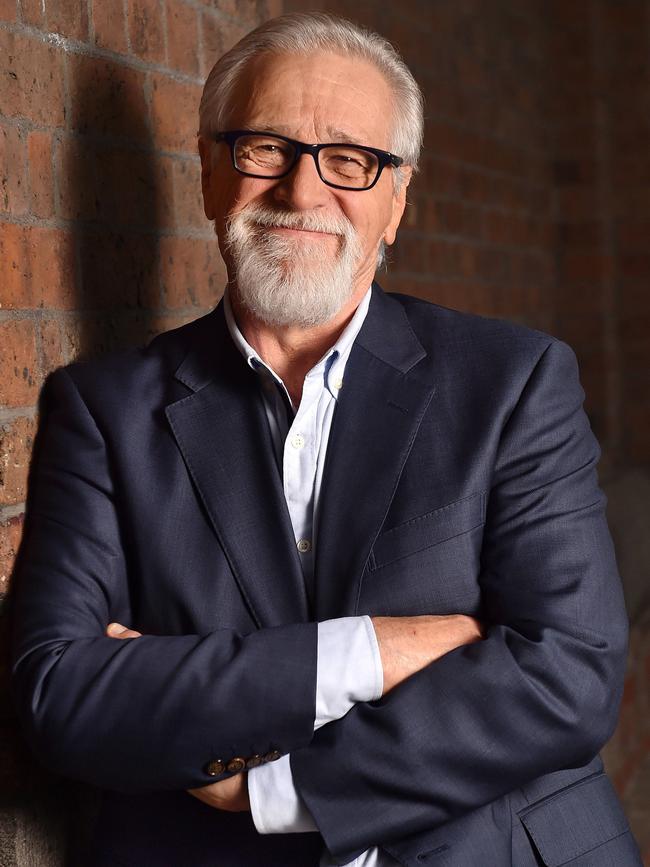

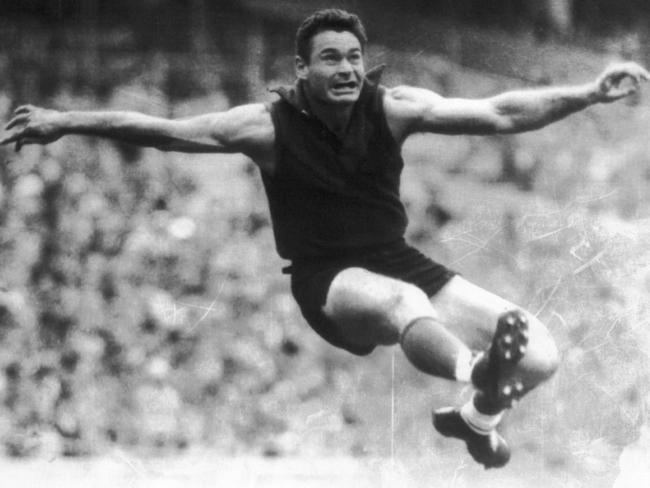

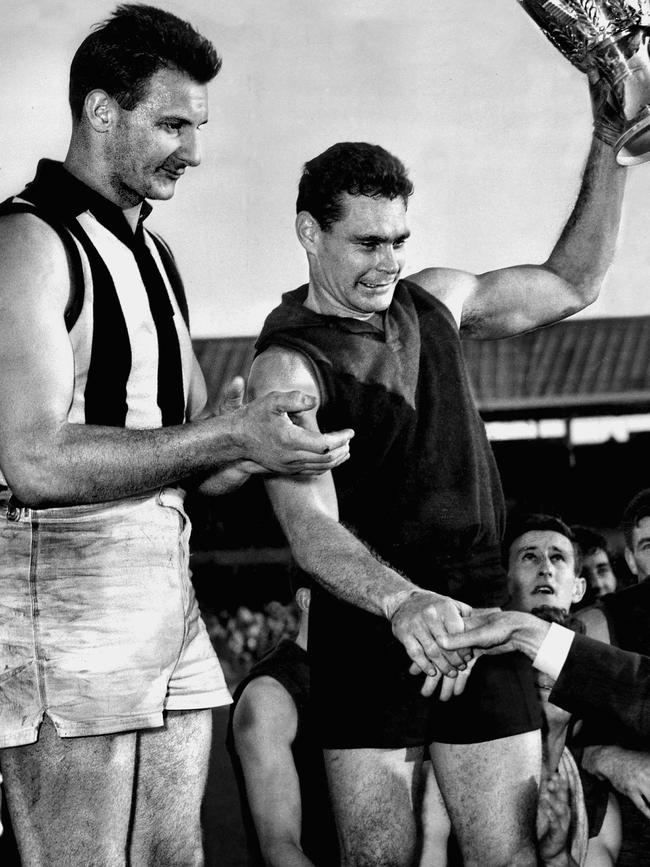

Smith contributed to 10 flags at Melbourne, four as a player and six as coach. He wore a halo later passed to his friend, Ron Barassi.

Smith issued orders like an army general, and expected them to be followed. He pioneered the team-over-individual rhetoric.

Smith scorned long hair and moustaches. Famed for his ruthlessness, he was feared and adulated, a kind of “father figure” to both his players and the game itself.

The Demons had won the flag in 1964. 3AW’s Neil Mitchell, then a paperboy of 12, had to work that day and couldn’t see his team win. “No worries, I thought, I will go next year,” he now says.

Mitchell’s confidence at the time seemed well placed. Over the previous 10 years, Melbourne had won six flags. Its competition dominance matched the Manchester United odyssey a few decades later.

The following year began, as expected, with wins in the first eight matches. There was a drubbing, inflicted by St Kilda, then two more losses punctuated by a win. Melbourne sat third on the ladder, out of form but well-placed.

Smith was watching a movie at his Pascoe Vale home on the Friday night before the next day’s game. There was a knock at the door. He was handed a termination letter. The club had sacked its lifeforce.

Smith’s unvarnished approach to communication had vilified him to board members. He had been aghast when the board did not support him after an umpire had launched defamation proceedings — Smith had called Don Blew “a cheat”.

Board members, meanwhile, were miffed that Smith had supported Barassi’s move to Carlton. There was a sense that the man was bigger than the club.

The team played, sans coach Smith, on Saturday and was beaten by North Melbourne for the first time in 12 years.

On Sunday, Smith went on television to criticise the club’s board. He seemed affronted when asked of a possible shift to Richmond; he was “Melbourne, through and through”.

He implied that the club would not recover. And he seeded the curse which pulses in his name to this day.

CONSPIRACY OF FORCES SURGING AGAINST THE DEES

The controversy bears no modern day comparison. Former Demon David Schwartz (once named as a victim of the curse for a string of knee injuries) points out if any coach had won the previous year’s flag, then the first eight games of the season, they’d be offered a five-year deal.

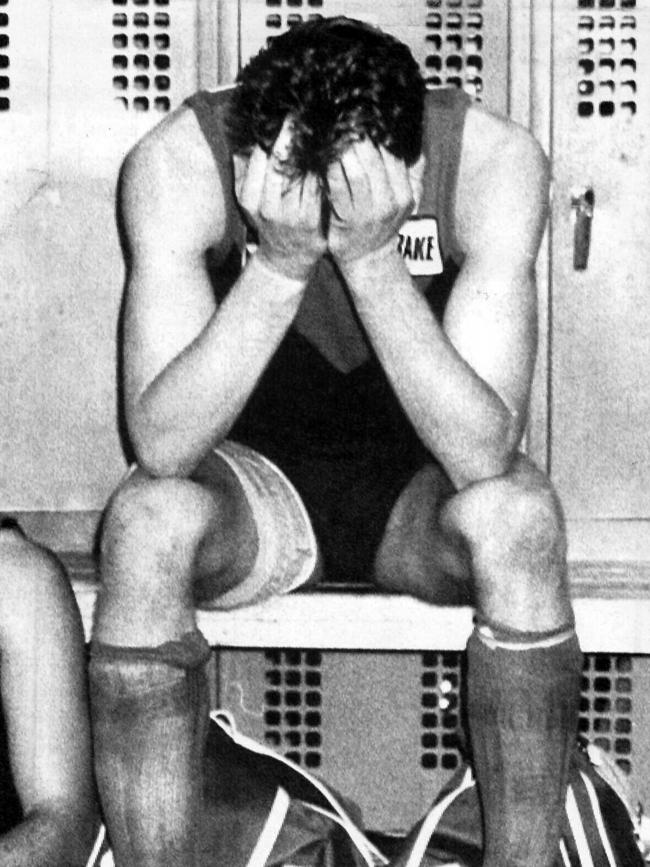

In the uproar, Smith was reinstated within two days. But the flame had been extinguished. Melbourne stumbled through the rest of 1965, missing the finals for the first time in 12 years, then the following year, then the following decade.

In hindsight, fans reached for answers, and concluded that Melbourne’s engine of assumed dominance had, overnight, spluttered and died in an in-house squabble.

The club would not reach the finals in the next 22 seasons. Over the span of 10 subsequent American presidents, and 15 Australian prime ministers, there was nothing.

When the team positioned itself for flag tilts, its form would dim, inevitably at the worst of moments, as if a conspiracy of forces was surging against them.

Mitchell talks of “unlosable games, world record beatings, and dear Jim Stynes running across the mark”, when the Demons were ahead on the scoreboard as the 1987 preliminary final siren sounded — and lost.

Adherents bestow the curse with insidious powers. So many Melbourne players have died prematurely, such as Stynes, Sean Wight and coach Dean Bailey, they say. The more serious minded fan seeks to dismiss the curse. At least one club legend describes it as unhelpful “bullshit”.

But Barassi has spoken of it.

He had returned to the club, to coach for five years from 1981, in a move that was supposed to signal a new beginning.

Melbourne inched closer to a flag, but not that close.

In 1988, the Demons lost a grand final by 96 points, a then record losing margin. In 1996, Melbourne agreed to merge with Hawthorn, an expedient choice which unravelled when Hawthorn voted against the move.

The merger decision fed the impression of a club which rolled over under pressure.

In 2000, Melbourne lost the grand final by 10 goals.

Apart from occasional flights of fancy, including spurts of optimism in the new millennium, Melbourne hasn’t until now really threatened to win a flag since.

By 2011, Barassi was moved to blame “the curse”. “I don’t know that Melbourne has fully recovered from the Smith thing,” he said. “They have done nothing to really get their pride back as one of the great teams of the VFL/AFL.”

CURSE OR COINCIDENCE?

If you believe in curses, you probably nod to footballing fairytales, too. Some of the omens this year are kind to the Demons.

They last won a flag in a Tokyo Olympics year. Of nine times finishing on top of the ladder, as they have this year, the club has won eight flags.

Like the Western Bulldogs in 2016, and Richmond the following year, most nonpartisan fans offer goodwill to the Dees for the upcoming weeks.

AFL chief executive Gill McLachlan admits to a soft spot. “You will see some romance if Melbourne gets there,” he says.

McLachlan agrees that it has been too long. Melbourne has languished flagless, after all, while Hawthorn has won 12 flags. Even poor old St Kilda has had more success since pre-decimal currency.

Schwartz nods to the curse — “fans never forget”. But he argues that plainer measures should be examined. He points out that Melbourne won 17 games from 88 played between 2012-15, the same number of home-and-away wins for 2021.

He traces Melbourne’s rise to six or seven years ago. Stars Christian Petracca and Clayton Oliver were drafted. The club has invested heavily in Steven May and Jake Lever who, despite serious injuries to both, have repaid the club’s belief.

“They knew they had some good midfielders, that was going to be the basis of the team, so I think it’s been building for a long, long time,” Schwartz says.

“If the forward line clicks I think they are the most dangerous side in the competition.”

He prefers to reduce the curse to a series of “big coincidences”.

“I saw what it did for the Bulldogs in 2016,” he says of winning a flag. “It gave them a badge of strength and belief. They became a fair dinkum club. And until Melbourne wins the flag they’re going to be ‘Oh, they’re only Melbourne’. If you win a flag it changes things.”

Long-suffering Melbourne fan Suzanne Considine says the team and club feels different this year. She laughs off the curse, but doesn’t discount its supposed power.

“I don’t think they carry that baggage around with them,” she says of the players. “Our youngsters haven’t had years and years and years and years of not getting anywhere. The youngsters have got so much more optimism. They haven’t lived with the disappointment and the heartbreak over and over and over.”

Sport’s most notorious curse was the “Bambino Curse” which enveloped the Boston Red Sox for three generations.

After the baseball club traded Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees, the Yankees soared over the next 86 years while Boston — struck by a series of monumentally unlucky moments — won no World Series.

Attempts to break the curse included the placement of a Red Sox cap on top of Mount Everest. In the end, winning was the only salve.

Mitchell knows that only a flag will end chatter of the Norm Smith Curse.

But he prefers to blame “Collingwood supporting evil football Gods”.

“I won’t dare to hope for a flag after 57 years, but this has been the strangest year I have had in a football watching life,” he says. “I still don’t trust them which is why to my shame I went to bed at half time and missed the win against Geelong last weekend.”

‘Cruelty on a massive scale’: Parks Victoria accused of huge roo slaughter

Parks Victoria has been accused of turning the state’s national parks into “killing fields” by slaughtering hundreds of thousands of kangaroos and joeys as part of its conservation management.

‘Complete disaster’: Fines urged for future camping no-shows

Victoria’s free camping trials has been described as a “complete disaster” with one MP pushing for fines to stop future no-shows.