Dylan Alcott’s off-court grand slam

Three-time Paralympic gold medallist and tennis ace Dylan Alcott won the 2018 Australian Open quad wheelchair singles title — his fourth — but in his new book he reveals the tough battle he was waging off the court.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Three-time Paralympic gold medallist and tennis ace Dylan Alcott won the 2018 Australian Open quad wheelchair singles title — his fourth — but he reveals in a new book he was waging a tough battle off the court.

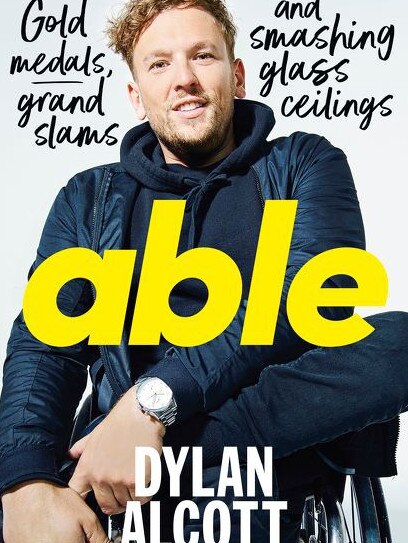

This is an edited extract from Aclott’s book Able, released on Monday.

THE expression on the doctor’s face as my brother Zack wheeled me back into hospital on Wednesday, January 24, this year said it all. I’d insisted on being released that morning, but I wasn’t in much of a state.

It had all started the previous Saturday. I should have been doing great. I’d spent that morning hanging out and having a laugh with one of Hollywood’s biggest names (Will Smith).

On top of that, I was the face of a national TV and print campaign that was raising my profile

to new heights. And I was prepared and ready to attempt a historic Grand Slam first in my hometown.

Why, then, did I feel so lousy? My head was killing me, I felt constantly on the verge of throwing up and everything ached.

ALCOTT ONE OF FOUR TO FIGHT OUT THE NEWCOMBE MEDAL

I’m an elite athlete. I train for hours every day, pushing my body as far as it can go. I know what hurting muscles feel like. This was something very different. Something bad.

I felt even worse on Sunday morning but tried hard to ignore it. No way could I possibly give

in to whatever this was, not when I was due on court at Melbourne Park in a mere three days to compete in one of the greatest tennis tournaments on the planet, the Australian Open.

Record numbers of people were expected. So many supported me, I couldn’t let them down.

When I finally took myself to hospital on Monday morning, the doctor told me a tiny cut on my leg had opened the way for the dangerous bacterial infection cellulitis. I need antibiotics, and fast.

I tried to explain that I needed to be well, I had somewhere to be very soon. But I couldn’t quite get the words out, and as the drip went into my arm, I gave up and sank back into an exhausted sleep.

Tuesday was a blur, broken by nurses changing the bag on my intravenous drip and taking my temperature. Waking on Wednesday morning, I had to fight the urge to fall straight back to sleep again.

In all honesty, I didn’t know how I was going to get to the end of the corridor, let alone get through a tennis match against one of the best players in the world. But I knew I had to try, and somehow I made it to the Open and got through the match.

Now, just a few hours later, I was back in hospital in a much worse state, feverish and vomiting. Once again I was admitted and once again I fell into a restless sleep.

The following morning, the doctor walked in to check on me just as I was preparing to swing myself out of bed and into my wheelchair.

ALCOTT WINS AUSTRALIAN OPEN TITLE

SCHWARZENEGGER TAKES ON ALCOTT

“What do you think you’re doing?” he asked in alarm.

“I’m going back to the Open,” I said. “Either you take this drip out or I pull it out. But either way I’m going now.”

Whatever it took, I was going to be there. I’d overcome the odd hurdle or two in my life already, so I wasn’t going to give in now …

MAKING AN ENTRANCE

UNTIL the moment I made my first appearance there was no indication that my life was in danger. Mum’s pregnancy progressed normally, and everything seemed just as smooth and ordinary as it had been almost three years earlier with my older brother, Zack.

Well, maybe there was a bit more discomfort below her ribs, but nothing to write home about. And the ultrasound done at 19 weeks didn’t show any abnormalities. My legs weren’t moving around much, but no one worried too much about that.

In fact, even after I finally arrived, two weeks late and weighing a whopping 4.5kg, I seemed like a healthy baby, except for the strange bulge the size of a man’s fist on my back.

It looked like a lump of fat and the doctor who delivered me told my parents not to be too worried. He’d seen cases like it before and usually the lumps were harmless and simply fell away over time.

For a few brief hours on that morning of December 4, 1990, joy was the prevailing emotion. Relieved and happy, Mum and Dad were looking forward to taking me home.

But soon everything changed, and they found themselves plunged into a nightmare all parents dread.

A paediatrician broke the difficult news. This wasn’t a simple cosmetic issue that would resolve itself. It was something much more sinister, something that would alter the course of all our lives.

MY parents (Resie and Martin) shared an optimistic and adventurous view of the world. As newlyweds starting their family, they moved from Sydney to Queensland and then on to Melbourne, where they made their home in a small cottage in Hampton.

The plan was to stay for just two years and reassess, but Mum fell pregnant with me, and my birth changed everything. If that fatty lump had been on my arm or leg, it might well have been nothing

to worry about. But its position indicated a very serious condition, the neural tube defect lipomeningocele.

Neural tube defects happen when key parts of the nervous system, the brain and/or spinal cord, don’t form properly in the womb. Spina bifida is the best known example.

With lipomeningocele, a tumour forms, either in the spinal canal or just outside it, and presses on the cord in a way that stops it growing as it’s supposed to.

No one could tell my parents why this had happened. All they could say was that it was a very serious condition that affected fewer than one in 10,000 babies in Australia.

As my true condition became apparent, Mum and Dad would need to dig deep.

The day after I was born, I was moved from Sandringham Hospital to the Monash Medical Centre a few suburbs away. There I was put under the care of the larger than life neurosurgeon Miss Elizabeth Lewis, a formidable figure who could have stepped out of the pages of a story.

Australia’s first female neurosurgeon and still working, Lewis was old school even back then. Although Mum and Dad were still desperately worried, they breathed a little easier knowing I was in such good hands.

But I was still less than two weeks old and needed to get stronger before any surgery could take place. So she told my parents to take me home for Christmas.

Officially, the idea was to get me as settled as possible and make sure I was feeding well. But even with a surgeon this good, there was no guarantee I’d survive the operation.

The unspoken understanding was that if worst came to worst, at least my parents would have had one Christmas with me at home.

Because the tumour was tethered to my spine, every time I was moved I’d scream in agony. This made it very hard to determine if things were getting worse.

All my parents could do was watch me continuously to try to establish a baseline of “normal” agonised screaming versus a sign that something else was going on.

In January 1991, at five weeks old, I was judged strong enough to undergo my first operation, intensive surgery attempting to remove as much of the tumour as possible.

“He might die tonight. He might not. We’ll see how he goes,” Miss Lewis told my parents in her typically blunt manner as they were wheeling me into theatre.

The operation took an incredible 13 hours, during which this extraordinarily skilled surgeon painstakingly removed most of the lipoma. Unfortunately, some was inside my spinal column and could not be touched.

No one knew what the consequences of this would be. Would I have feeling in my legs? Be able to walk? Would I even survive long enough for that to matter?

I recovered in a ward known as 42 North — a 30-bed ward used for paediatric surgery, acute adolescent medicine, and renal and neurosurgical procedures. Over the years, I would come to know it all too well.

This hospital would prove to be my de facto home for much of the first three years of my life, and I returned there for stays throughout my childhood. In fact, for the first part of my life I knew that ward better than I knew our family home.

Even some of my close friends don’t really know about this period in my life. It’s painful to revisit because it was so awful for everyone involved. My parents and wider family were put through the wringer, constantly taking me to hospital, fearing I might die on multiple occasions. And even a “good patch” for me was difficult for them, because my condition brought about a total upheaval of family life for them and my brother Zack.

Mum and Dad were determined to do whatever it took to support me and made a commitment to never leave me in hospital by myself. Never. Think about the dedication that required.

Dad was a sportswear marketing manager. Mum had given up paid work to raise children, but was hairdressing at home on the side, and toddler Zack was already keeping her pretty busy even

before I came along.

Sometimes Mum and Zack would sit with me all day while Dad was at work. When he arrived at the hospital, Mum would take Zack home. They’d swap their parking tickets when they switched to save money.

Dad would then try to get some sleep in the armchair next to my cot until the next morning, when Mum would return with a fresh suit for him, and off to work he would go again.

The strain must have been enormous, and of course it affected Zack, too. He’d gone from being an only child with as much attention as he needed to the eye of a crisis he couldn’t possibly understand.

ALL seemed to be going well in the period immediately after that first operation. But my parents soon found out how quickly things can change.

Ten days after the surgery, Dad was with me one night when my breathing became shallow and strained and I began to swell up in the most alarming fashion, right before his eyes.

Dad was so alarmed he asked the nursing staff to phone Miss Lewis at home, who, on hearing my symptoms, rushed to my bedside, despite the late hour.

“We’re going to give him what I hope is an almost lethal dose of steroids,” she announced. “It will either stop the swelling and fix him, or it will kill him. If he’s alive in the morning, then we’ve done the right thing.”

Dad stared at her dumbstruck. But when he’d gathered his senses, he rang Mum and asked her to come in to the hospital. It might be time to say their goodbyes to me.

While Dad waited for Mum, he took out the little camera he had with him and tried to focus through his tears. The photo he took shows me lying in the cot, a distorted figure, next to a blue teddy bear my parents had hoped would bring me luck. My eyes are squeezed tight with pain.

I can’t even begin to imagine how Dad must have been feeling, thinking that this was perhaps the last photograph he would ever take of me.

Over the next few hours, my parents were in shock and despair. Telling me the story of this time, their memories are still painfully vivid, giving me some inkling of the torture they went through as they waited to see if I’d live through the night.

For hour after terrible hour they stood beside my cot, waiting for the swelling to come down, willing me to breathe easier, longing for some good news in the long, dark night.

The clock moved so slowly it seemed to have stopped. Finally dawn approached. Could it be that I looked just a little better, or was that just their own exhaustion and wishful thinking?

At 8.30am, the sound of Miss Lewis approaching briskly sent their heart rates skyrocketing.

My parents looked at the neurosurgeon’s face, always so inscrutable. Was that the flicker of a smile beneath her stern expression?

Miss Lewis examined me, then studied my chart while my parents forgot to breathe. Finally, she looked up. “You don’t have to worry about this one,” she said. “He’s a fighter. He’ll be fine.”

EDITED EXTRACT FROM ABLE, BY DYLAN ALCOTT, ABC BOOKS, RRP $40, OUT MONDAY

RELATED CONTENT