More than two decades on, court hears latest chapter in Claremont serial killings case

Did an awkward, socially isolated boy with a fetish for women’s underwear graduate to a prowler, then rapist - and finally one of Australia’s most elusive serial killers?

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

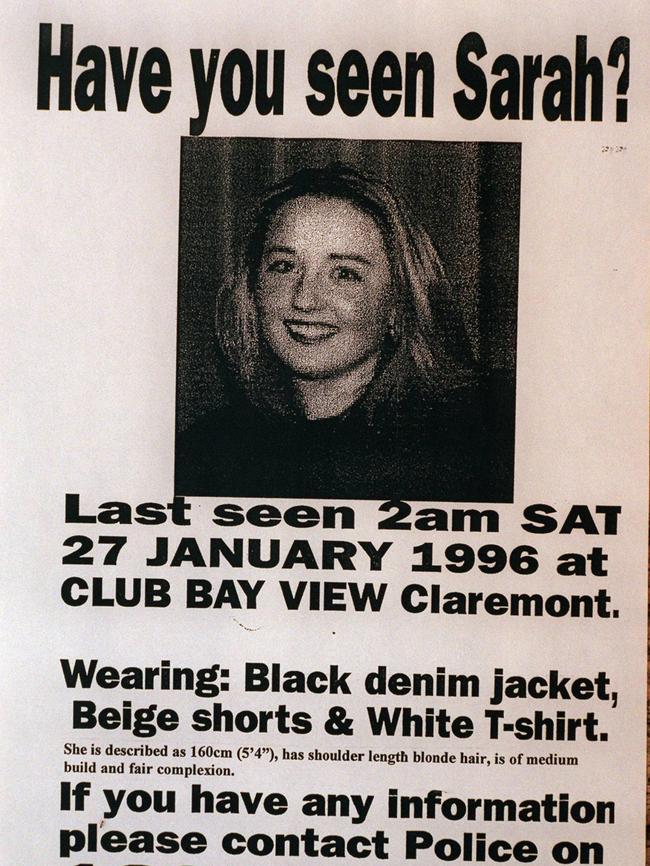

It was just before 2am when a tired Sarah Spiers told a friend she was going to grab a cab and head home for the night.

It was January 27, 1996, and as 18-year-old Sarah descended the nightclub’s stairs alone, she stopped and chatted briefly with the doorman before heading to a nearby phone box to book her ride to South Perth.

Records show a call was placed at 2.06am, with Sarah telling the taxi dispatcher she would be waiting at the corner of Stirling Highway and Stirling Rd in Claremont, a leafy western suburb that’s home to a vibrant night-life scene.

MORE CRIME

ANDREW RULE LIFE AND CRIMES PODCAST

MELBOURNE SUBURBS” MOST SHOCKING KILLINGS

But when the cab arrived exactly eight minutes later, Sarah had vanished.

One of Australia’s most baffling murder mysteries, which would become known as the Claremont serial killings, had begun.

Australia Day had fallen on a Friday that year and Sarah had been celebrating earlier in the night at Cottesloe’s Ocean Beach Hotel with a group of girlfriends.

The fun continued until midnight when Sarah’s elder sister Amanda picked them up and drove them the short distance to Claremont, before dropping them near Club Bay View.

The two sisters shared a house and it was common for Amanda to give her little sister a ride when she needed one.

But after waving Sarah goodbye, Amanda headed home and would never see her sister again.

Police know Sarah had been waiting for her cab because she was spotted by two men in a car that had stopped for a red light at the intersection of Stirling Highway and Stirling Rd.

One of the men commented to his friend that he did not think it was safe for a young woman to be out alone because of a spate of recent high-profile sex attacks in the area.

When the lights turned green and the men drove off, the driver noticed in his rear-view mirror another car approaching the intersection from behind him.

That car appeared to turn off at the lights and the man assumed it was Sarah’s taxi arriving to pick her up.

Sarah’s failure to arrive home the next day would spark a series of frantic phone calls between Amanda and Sarah’s friends.

All had assumed she got home safely and the sense of panic grew steadily over the weekend.

When Sarah failed to show up at her secretarial job on Monday morning, her father Don Spiers took his concerns to police.

By that stage, an army of Sarah’s friends and family members had already begun handing out flyers in Claremont asking if anyone had seen Sarah.

A few days later, Mr Spiers and detectives from the homicide squad would appeal for help.

“Sarah was a very caring person and was very attached to Amanda who was her best friend as well as her sister,” a distraught Mr Spiers said when he was asked to describe his daughter.

“For her not to keep in contact with Amanda is very strange.”

To everyone who knew Sarah, her disappearance was totally out of character.

She was a girl any parent would have been proud of — responsible, loving, considerate and not someone who would have accepted lifts from strangers.

As the days turned into weeks, police began preparing the family and the public for the worst.

“Reality must take effect eventually that the young lady has come to harm,” Det-Insp. Paul Ferguson told a press conference a fortnight after Sarah was reported missing.

Inquiries would continue, but police were finding they had little to go on.

Insp Ferguson, now retired, said it was as though Sarah had vanished into thin air.

“No one had seen her get into a car, there was no crime scene to provide us with any forensics … and there was no body to tell us what type of offender we were dealing with,” he said.

As unlikely as it was, police also had to consider the possibility that Sarah simply did not want to be found.

But four-and-a-half months later, any hopes of finding her alive would evaporate.

Another young woman had disappeared from the streets of Claremont.

THE CLAREMONT SERIAL KILLINGS

These are three of the most well documented murders in Australian history.

January 27, 1996 — Sarah Spiers.

June 9, 1996 — Jane Rimmer.

March 15, 1997 — Ciara Glennon.

Three young women snatched from the streets of Claremont.

Together, the crimes became known as the Claremont serial killings.

And finally — after 23 years, a million pieces of paper and almost as many theories, rumours and anecdotes — the case against the accused, Bradley Robert Edwards, began this week with pre-trial directions in the WA Supreme Court.

Lead prosecutor Carmel Barbagallo painted a picture of the 50-year-old Edwards as evolving from an awkward, socially isolated boy with a fetish for women’s underwear to a prowler, then rapist and finally a killer.

Ms Barbagallo said she wanted to allege that Edwards prowled an area a kilometre around his family’s home in southeast Perth wearing — and stealing — women’s clothing, beginning in 1988.

Spotted wearing kimonos, satin night gowns and, in one case, underwear on his head, the then teenager was said to be building up to an attack on a young woman in her house, while her parents slept nearby.

On February 15, 1988, the teenage girl — who was aware of Edwards through her brother but did not know him — was accosted in her bedroom, subdued and gagged, the prosecution alleged.

No one was ever caught but the court was told a kimono dumped at the scene became crucial almost 30 years later when it was tested — and Edwards’s DNA was allegedly found on it.

Latent prints from one of the break-ins were also matched to Edwards and foot impressions from the time did not rule him out.

Ms Barbagallo said Edwards was the prowler and the attacker, with a “fetish” for collecting women’s underwear.

In 1990, it emerged that he also had developed a taste for grabbing lone, vulnerable women.

A day after being told by his then wife that she had been unfaithful to him, Edwards went to work at Hollywood Hospital and grabbed a social worker from behind before trying to drag her away. She fought him off. He was arrested, charged and convicted of common assault.

But Edwards did not lose his job. And by the mid-1990s, it is alleged he was prowling again — this time in his car.

“We say this is the manner in which he goes about identifying his victims in Claremont … he prowls in Huntingdale and he prowls in Claremont,” Ms Barbagallo said.

Edwards is said to be the man who was driving around the Claremont area in his Telstra work vehicle offering a series of lone women lifts.

The court heard he allegedly told one woman that “he was looking for damsels in distress like her”.

On five occasions between 1995 and 1996, a man in a Telstra van — or who said he worked for the telco — made such offers to women, the prosecution claimed.

On one of the occasions in question, the woman was followed, grabbed and kissed. Another said she got into the vehicle believing it to be a taxi.

In the same time span, Edwards is also accused of the brutal abduction and rape of a teenage girl who was tied up and dumped in Karrakatta Cemetery.

DNA from the attack has been matched to Edwards, the court was told.

Less than a year later, the first Claremont murder happened.

Ms Barbagallo, who was a young lawyer when the abductions occurred, told how first Ms Spiers, then Ms Rimmer and finally Ms Glennon went missing.

All three, she says, were taken off the street, late at night, by Edwards and brutally killed.

Sarah Spiers was leaning against a Telstra bollard waiting for a taxi she had just called. A nearby cab was dispatched, but when it rolled up, there was no sign of her.

The driver continued along Stirling Highway, and picked up three other women. One of the taxi passengers actually knew Ms Spiers. No one saw her then, or ever again.

But Ms Barbagallo says someone might have heard her.

About 3am, in Mosman Park, “a series of bloodcurdling screams” were heard by a resident.

When they looked, they saw the back of a car with distinctive curved brake lights, and a glaring registration plate, the court was told.

Ms Barbagallo said that, at the time, Edwards had access to a 1992 Toyota Camry, which shared those distinctive features.

Ms Spiers’ body has never been found.

Jump forward just a few months, and Jane Rimmer is last seen standing next to a pole outside the Continental Hotel in Claremont, after a night out with friends.

Later that night, the court was told, two witnesses living nearby Woolcoot Rd, Wellard, hear a “loud, high-pitched female scream which stopped abruptly and was followed by silence”.

A watch was found later that day, on the same road.

But it was another 55 days until Ms Rimmer’s decomposed body was found near that road, partially covered in branches, but with no personal effects nearby.

Ms Barbagallo revealed that two months later, a knife similar to those that were standard issue to Telstra workers at the time was found on the same road.

No Telstra work had been done in that area at the time.

And two more of the same knives were found when police raided Edwards’s home in late 2016.

Even more revelatory were 20 fibres allegedly found in Ms Rimmer’s hair and matched to the seat insert and seat bolster of a 1996 Holden Commodore — the same type of car Edwards had been issued by his work at the time.

Remarkably, that car was found by police in December 2016, and a comparison of fibres was carried out.

Ms Barbagallo said the fibres found on Ms Rimmer could not be linked directly to that car but they were from the same make and model.

Ciara Glennon went missing after some late-night revellers saw her walking near Hungry Jack’s on Stirling Highway and then talking to the occupant of a late-model, white Holden Commodore.

On that same night, Edwards was supposed to spend the night with friends 100km away in the coastal town of Dawesville. But he didn’t show up until the next morning, telling his friends he was trying to reconcile with his wife that night. That was a lie, the court was told.

Rather, Edwards was allegedly snatching Ms Glennon, slitting her throat and dumping her body.

When her body was found 18 days later, the method of covering it bore a “strikingly similar” resemblance to how Ms Rimmer’s body was covered.

Fibres on Ms Glennon’s body also matched the same make of Commodore that had apparently shed clues about Ms Rimmer’s death.

And when police examined Ms Glennon’s body they found a mixed DNA profile under her fingernail and thumb that matched her DNA and, much later, allegedly that of another person — Edwards.

Pornographic material found on Edwards’s electronic devices more than two decades later allegedly showed he had an “obsessive sexual interest in the abduction and rape of women”.

The prosecution also drew a connection between these violent crimes and periods of extreme emotional turmoil in Edwards’s life.

Ms Barbagallo said that in January 1996, Edwards’s first wife told him she was having an affair, that their marriage was over and she was leaving.

He said that in May that year, Edwards learned his wife was pregnant to her new partner.

“We are not saying it was causative but it is significant to the timing of things,” Ms Barbagallo said, adding he had a tendency to take out his frustrations on women who were strangers, not those he was involved with.

When Ms Spiers disappeared in January 1996, the marriage was over and Edwards’s wife had moved out of the marital home, Ms Barbagallo said, adding that during the time line covering all three alleged murders Edwards was living alone in his former marital home.

In May 1996, Ms Barbagallo said, Edwards’ first wife told him she was pregnant to her new partner.

Ms Rimmer was abducted and killed the following month.

From October to December 1996, Edwards had a sexual relationship with a woman 20 years his senior but ended the relationship when she wanted more from him.

Ms Barbagallo told the court Edwards met his second wife in 1997 — in the weeks after he allegedly murdered Ms Glennon.

She said Edwards was not alleged to have committed any crimes since then.

Bradley Robert Edwards has pleaded not guilty to all charges.

Justice Stephen Hall noted the details set out by Ms Barbagallo were “all allegations” and that no evidence had been put before the court at this stage.