Conscription fight that divided Australia

AS our soldiers massed for the charge of Beersheba, a battle raged back home in Australia over whether we should conscript men to fight in World War I.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Casey’s army cadet agenda: Council wants to bring back conscription

- Vietnam War protests 1970

- Casey councillors vote in favour of compulsory military service to help curb youth unemployment, crime

- Role of Coburg and Brunswick in Centenery of 1916

BILLY Hughes knew how to fight and win.

Our seventh prime minister led Australia — and two vastly different political parties — from 1915 to 1923.

He was one of the most prominent and vociferous allied leaders in talks over the Treaty of Versailles, the treaty that mapped out relations between Germany and the rest of the world after World War I.

But there was one battle he couldn’t win, despite two bitter and divisive referendums in less than 14 months — the fight to introduce conscription and force able-bodied men to fight on the hellish battlefields of Europe and the Middle East.

One hundred years ago this week, as Australian Lighthorsemen massed in Palestine for the legendary charge of Beersheba, Australians at home were gripped by one of the most tumultuous political battles we’ve ever waged, with a divisive referendum on conscription just weeks away.

Hughes was already an old political campaigner before he became prime minister in 1915, as the Great War gathered pace.

He was a NSW state MP from 1894 to 1901, before he switched to federal politics as the member for West Sydney at Federation in 1901. His style was combative.

Hughes was first external affairs minister, then attorney-general in several Labor governments.

He was a vocal opponent of first prime minister Edmund Barton’s plans to defend Australia with a small professional army, favouring universal military service. Conscription was introduced in 1910, but only for home defence.

When the Great War erupted in September 1914, Australians enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force en masse — more than 52,000 by year’s end, and another 165,000 in 1915.

Wartime leadership weighed heavily on Labor PM Andrew Fisher. With ill health, he stepped aside for Hughes in October 1915.

Hughes left Australia in January 1916 to join crucial war planning with allied leaders in London. He toured Western Front battlefields, spending time with soldiers and hardening his belief that conscription was essential.

At home, things were changing radically.

A campaign to drive volunteer enlistment began in November 1915 and was initially successful.

But word began filtering home that the AIF was suffering terrible losses, changing public sentiment towards the war, dramatically cutting enlistment and leaving the nation stretching to replace lost troops.

The Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916 in which the Irish pushed for home rule, radicalised many Irish Catholics against Britain, and the union movement (which controlled the ALP) was dead against conscription.

Britain and New Zealand had implemented conscription early in 1916, before the horrors of the western Front.

Australia’s official war correspondent, CEW Bean, recorded that in July and August 1916 alone, the AIF lost 28,000 men either killed, injured or missing, most on The Somme and at Pozieres.

By the time Hughes returned in July 1916, Australia was recruiting only 4000 men a month. The Germans seemed to be on top.

On August 31, following talks with military brass, Hughes announced his plan to change the Defence Act (1910) to allow conscription for overseas service via a national non-binding vote referendum.

The referendum question asked: Are you in favour of the government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this war, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth?

Opposition festered within the ALP, with many MPs aligning with their union or Catholic roots.

On September 15, 1916, Hughes left Labor, declaring: “Let those who think like me, follow me”. 24 of Labor’s best and brightest did.

Hughes stitched up a confidence and supply deal for his new Nationalist Labor Party with the conservative Commonwealth Liberal Party and continued as PM.

The messy affair reflected the schism now running through the rest of Australia on social, political and religious lines.

Firebrand Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix — of Irish extraction and anti-British — led the charge against conscription.

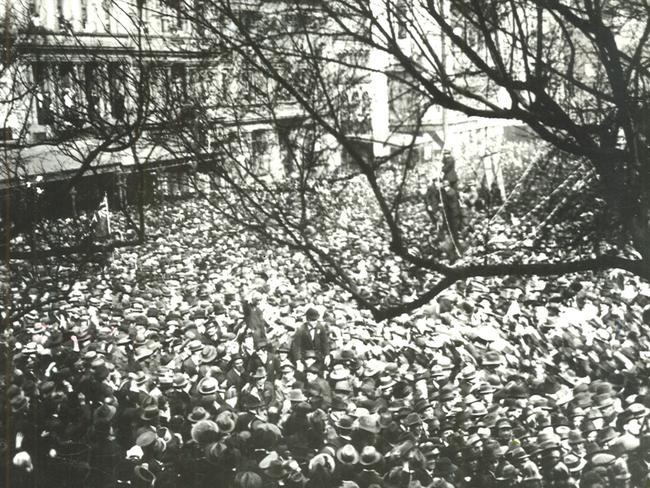

The bitter debate pitched friends against friends and relatives against relatives, inciting mass rallies for both sides that attracted tens of thousands in Sydney and Melbourne.

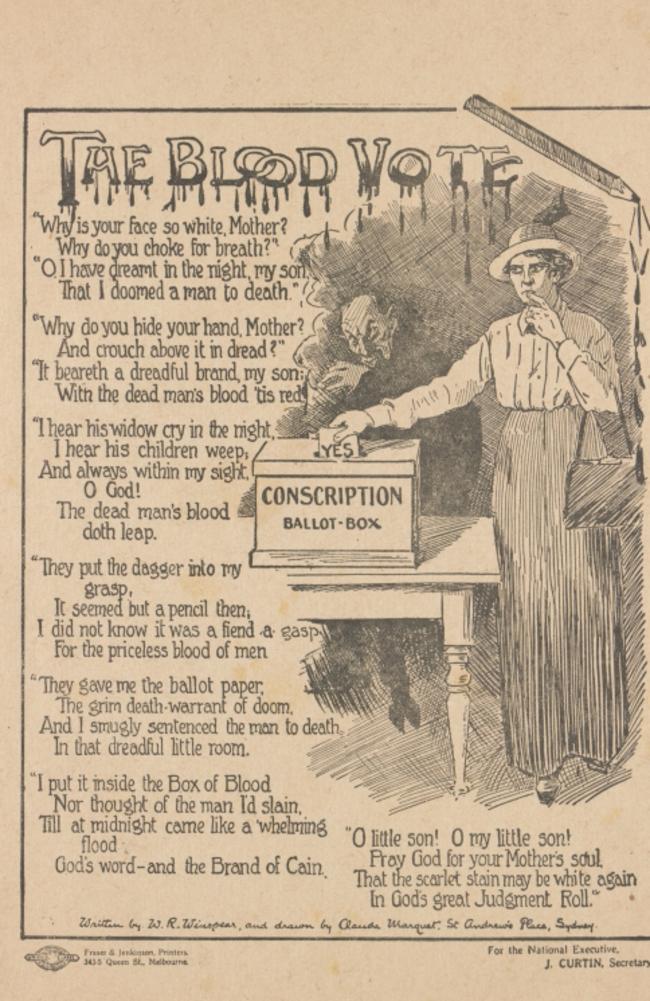

Some rallies were targeted at the relatively new and powerful women’s vote.

The pro-conscription side argued that non-volunteer military service was absolutely necessary to maintain Australia’s commitment of to the allied effort, with some intimating that any other position was cowardice.

Anti-conscriptionists believed it was wrong to send non-volunteers to fight, kill and possibly die. Unionists worried cheap foreign labour would flood Australia with conscripts overseas.

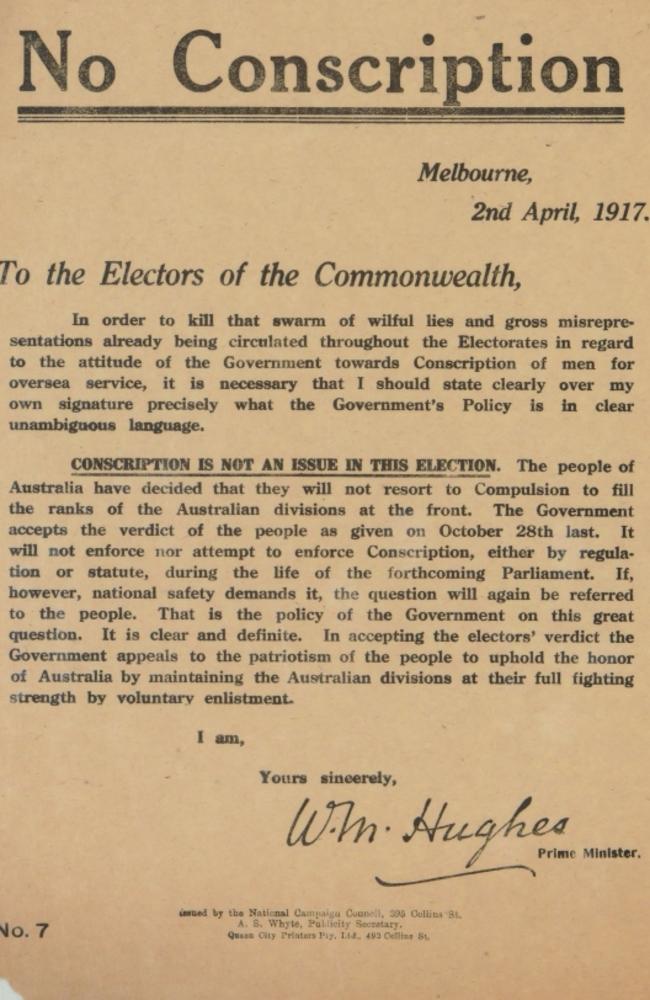

The referendum on October 28, 1916, was narrowly defeated. It achieved a majority in the Federal Territories and three states — Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia — but it fell more than 72,000 votes short of a majority of more than 2 million eligible voters.

Perhaps Hughes campaigning was flawed, or the powers he sought were too broad and far-reaching.

Despite the loss, the issue remained politically charged into 1917, with recruiting still less than 4000 a month. Only 45,000 volunteers enlisted that year, down from 142,000 in 1916.

Hughes’ Nationalist Labor Party and the Liberals united as the Nationalist Party in February 1917, and comfortably won the May 1917 election, Hughes now representing Bendigo in Victoria.

Soon, British leaders pleaded to Hughes for another division of troops. Again, Hughes raised conscription. Simmering societal tensions erupted.

The campaign was again marked by bitterness and, in some instances, violence.

By this time 100 years ago, the second referendum was set for December 20 and the battle was on.

Hughes promised to resign if the yes case did not prevail. The question was simpler: Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth Government for reinforcing the Commonwealth Forces overseas.

Big rallies were held around the nation again. Emotive political advertisements littered the press. Hughes even made a film to push the yes case.

Queensland was a flashpoint for protest and dissent.

Then-premier TJ Ryan was a leading anti-conscriptionist. In an effort to muster support, Hughes toured southern Queensland.

Hughes ordered police to raid the Queensland Government Printing Office in a bid to confiscate copies of the state parliament’s Hansard, which he said contained subversive anticonscription talk.

Passions boiled over in Warwick on November 29, when Hughes was hit by two eggs at a rally, then accused a local policeman of refusing to arrest his assailant and of breaching Commonwealth law.

The policeman was exonerated shortly after, but an incensed Hughes ordered the formation of the Commonwealth Police (now the Australian Federal Police).

At the end of another brutal campaign, the no case won.

This time, the yes camp carried Western Australia, Tasmania and the Federal Territories by smaller margins and narrowly lost in Victoria. Overall, the yes campaign was 166,000 votes short.

Interestingly, votes from men serving in the AIF were divided, with 103,000 for conscription, 93,000 against.

The Nationalists cast a vote of no confidence in Hughes. He resigned but, with no obvious successor, governor-general Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson immediately recommissioned him and he remained PM until 1923.

Conscription was dead in the water.

Less than a year later, on November 11, 1918, the armistice ended the war.

More than 330,000 men enlisted to fight for Australia in World War I. Of those, almost 60,000 were killed, 152,000 were wounded and 4000 were captured as prisoners of war, with 395 dying in captivity.