Celebrating 40 years since Australia’s first ‘miracle’ IVF baby was born

For Australia’s IVF pioneer John McBain it was a feeling of pure elation when the first woman successfully conceived through the program in 1979. Now, four decades later it’s responsible for helping thousands of families.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

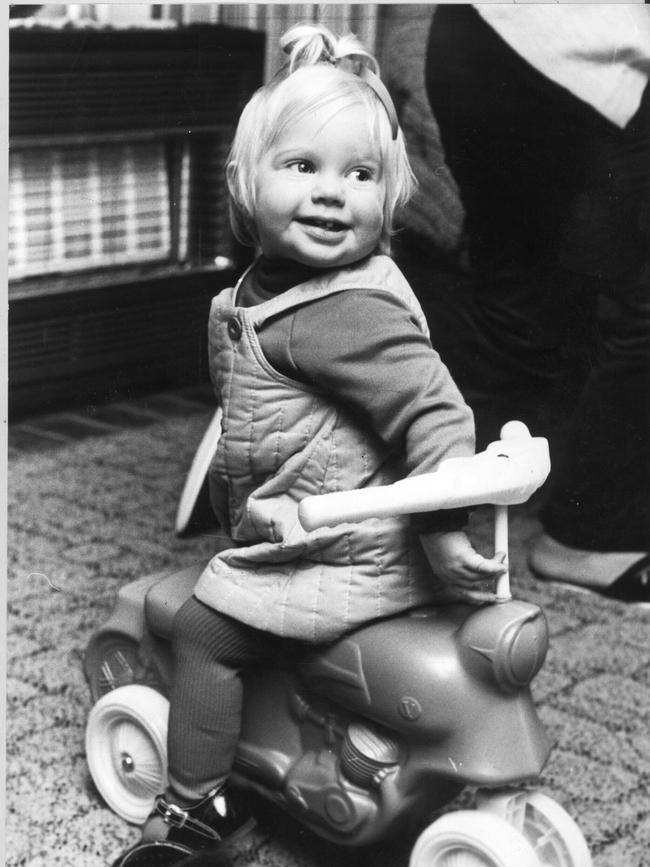

From the minute baby Annabelle Kosmatos wakes, her giggles fill her family’s Thornbury home.

Just 10 months old, she already knows how loved she is — but she doesn’t yet know just how special a journey she has taken into her parents’ arms.

Annabelle is one of the thousands of children born through in vitro fertilisation (IVF) since Australia’s first “miracle” baby arrived on June 23, 1980.

Forty years ago, women longing to be mothers and men hoping for a child had little more than a glimmer of hope. It was the hope this new technology — that had never before worked in Australia — could complete their families and create a child in vitro.

It was a dream many so desperately desired, but back then few could achieve — or even afford to try. When IVF first began in Australia, there was just a 2 per cent chance of success.

“Of the 50 women we treated in 1979, only one woman became pregnant,” IVF pioneer Associate Professor John McBain recalls.

“I had been working in IVF for three years before the first pregnancy (in Australia) happened — and it was such a wonderful relief to know it could happen.”

McBain, who is now retired, still remembers the feeling of joy when he and the team at the Melbourne Egg Project realised their first pregnancy had been successful. The project brought together doctors from Queen Victoria Medical Centre, now Monash Medical in Clayton, and The Royal Women’s Hospital, which now includes Melbourne IVF, and was instrumental in the success of IVF in Australia.

“I remember getting the blood tests (to indicate the first successful pregnancy) — it was

a feeling of pure elation,” McBain says.

“It put us on the very early steps of the road we’re on now — but it was by no means a turning point.”

But many would argue it was. In the 40 short years that have passed, more than 200,000 babies have been born in Australia through IVF.

McBain — one of the longest-serving IVF doctors in the world — and fellow pioneer

Dr Ian Johnston were there for some of the biggest breakthroughs.

The first was the ability to freeze embryos in liquid nitrogen, which could then be thawed and still have “a good chance of pregnancy”.

That was in 1984. And in the years that followed, McBain and his team became leaders in IVF.

One of McBain’s proudest moments was campaigning for a maximum of two embryos

to be placed inside the womb, instead of four.

He describes the practice as “buying four tickets in a draw,” but says it also posed the risk of multiple embryos growing and all four failing. If only two were used, this risk decreased and any remaining embryos could be frozen and used down the track.

“The freezing of embryos reduced that bad outcome,” McBain says.

Overcoming male infertility and injecting sperm straight into the egg was another major milestone McBain and his team were involved in bringing to Australia.

The practice was developed in Belgium,

but became available in Melbourne in 1993.

It meant women no longer had to use an unknown donor and could instead create an embryo with their chosen partner.

McBain said this “revolutionised” male infertility.

Across the decades, as technology advanced so too did the high science of IVF.

A new test was developed to determine whether an embryo was chromosomally normal, to inform women and families if an embryo was not viable, or likely to end in miscarriage.

Other teams had developed a way of testing five chromosomes for abnormalities, but McBain and his team led the charge in testing all 24.

“We worked out a way to do all 24 at the one time — and our first chromosomally normal baby was born in 2000,” he says.

The chromosome test is now routine for women undergoing IVF, especially those aged 38 and over, who are at an increased risk of having a baby born with abnormalities.

“That means pregnancy happens much more quickly and we’re able to tell someone straight away that there isn’t a (viable) baby among those other embryos,” he says.

Today, women can freeze their eggs, embryos and ovarian tissue.

For Associate Professor Kate Stern, a fertility preservation specialist at Melbourne IVF and The Royal Women’s Hospital, giving women this choice has been her “heart and soul”.

This is especially true of young people going through cancer treatment who would otherwise be left infertile.

“If you can’t do anything for those patients, it’s like a double whammy,” Stern says.

“If you’re about to have treatment for breast cancer or bowel cancer or leukaemia, what we can now do is get the eggs, if they are post-pubertal, and freeze them. And we’re looking at how young can a girl be for us to freeze her eggs — even as young as a 13 or 14-year-old.”

But it’s preserving ovarian tissue that is perhaps the most compassionate advancement.

It’s given young girls and women who are not yet at reproductive age, or who need urgent cancer treatment, the ability to freeze tissue that can be thawed for use later in life. Incredibly, the tissue has also been proven to generate egg growth when placed in the abdomen.

Stern says such technology is driven by patient needs.

“And, thank goodness, it’s paid off,” she says. “There’s now over 140 babies that have been born via ovarian tissue grafting.”

Stern’s passion for her work, and for helping women and families, is clear. It’s driven her to help set up a national program to freeze and store tissue for people in need across the country.

“Tissue is very hard to freeze and it can be

a complex discussion with parents about (if it

is right for) their little kid,” Stern says.

The program will see Stern and her team liaise with local specialists, who will take the tissue before it is transported back to Melbourne.

It’s these advancements, Stern says, that will give the next generation a choice when it comes to fertility.

After almost 25 years in the game, she says the changes in IVF treatment have been “enormous”.

“In the old days it was a miracle — it was amazing, it was so experimental. Even in ’97,

we told women there’s a 7.5 per cent chance of becoming pregnant. Now it’s like a 35-45 per cent chance and people say, ‘why isn’t it better?’”

The next target is to see if young boys can also freeze reproductive tissue if undergoing treatment for cancer or other diseases, which Stern admits she is still not sure will work.

But a recent study in monkeys has shown it is possible to have a baby with sperm matured outside the testis.

“New things are happening — and they’re going to make it better for women and men,” Stern says.

In her eyes, making IVF available and affordable to women has been one of the country’s greatest achievements.

“At The Women’s now, you can have

low-cost IVF, and at Melbourne IVF we

have premium care with all the top science

— and that’s what I’m so proud of,” she says.

“Between 5 and 6 per cent of children in Victoria are born via reproductive technology and one in six couples have infertility problems. No one should not have fertility treatment because they can’t afford it. We’re so lucky in Australia.”

FIRST BABY BORN THROUGH IVF

It was nothing short of a miracle the day Candice Reed — now Candice Thum — was born.

As Australia’s first baby born via IVF — and just the third IVF baby in the world — it had been years in the making.

As her eyes opened on this big, bright world, so too did the opportunity for some 200,000 “IVFlings” whose births have since followed her own.

As she celebrates her 40th birthday on Tuesday, Thum reflects on that hope and the thousands of “beating hearts” born since 1980.

“I look back now and marvel at how my parents must have felt when they received the phone call from Ian Johnston to tell them they were pregnant,” Thum says.

“(Now) there is at least one child in every classroom across the country born through fertility treatments. That’s a lot of IVFlings making their mark on the world and a far cry from when I was the only kid in my region — let alone the classroom — born through fertility treatment.”

Each one, she says, is a “hope-holder” for women, men and families in Australia and abroad.

“It was a miracle then, and still is to each

and every person who bravely faces fertility treatment,” she says.

Like Thum’s parents, Mary and Angelo Kosmatos were holding out hope for their “miracle” child.

The Melbourne couple, who welcomed baby Annabelle to the world last year, are living proof of Thum’s legacy.

Mary, who is one of Stern’s patients, froze her eggs at age 38 after she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Doing so allowed her to focus on her health without giving up her dream of being a mum.

And when Mary met now-husband Angelo three years later, everything fell into place.

“At that time I was 43 years old — and because of my age Kate advised that if we go through all the eggs I may not have any left,” she says. “So we did a fresh (egg collection) cycle, which was successful, and Annabelle was the only genetically viable embryo.”

Nine months later, Annabelle was born happy and healthy.

“She’s everything and more than what we expected,” Mary says.

You can hear the joy of being a mum in her voice — and it’s something she wants other women to know they can have, too.

“For women that have certain fertility challenges, I think it’s amazing that we can have this (IVF) in our society,” Mary says.

“And I know it’s still probably seen as a bit

of a taboo — but I don’t think it’s anything anybody should be ashamed of or even think twice about.

“How that baby gets here — it doesn’t matter. It’s having a healthy baby that you’ll nurture and love for the rest of your life.”

She says 10-month-old Annabelle has given her and Angelo “a lot of joy”.

“There’s always a lot of laughter in our house,” she says. “From the minute she wakes up we can hear her. She’s such a bright little girl. She’s an absolute joy — she’s given us absolute joy. And we love being parents. Sometimes you just have to take a leap of faith.”

MORE NEWS:

INSIDE LYGON ST’S FIGHT TO SURVIVE VIRUS LOCKDOWN