Cane toad for dinner? Eat the Problem cookbook puts invasive species on menu

Fancy a cane toad for dinner? How about a fox curry? A new cookbook is putting invasive species on the menu, because if you can’t beat them, why not eat them.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Kirsha Kaechele wanted to taste cane toad, so she placed an order with toad hunters in Northern Australia, expecting a batch of skinned legs to be dispatched.

The plan was to sweet-and-sour the limbs to sample ahead of the recipe’s inclusion in her new cookbook on invasive species, Eat the Problem, which was launched last week.

“They had to be dead,” Kirsha says of the consignment of the invader species, which was introduced to Australia from Hawaii in 1935 to take on native beetles feasting on sugarcane crops in Queensland.

REGIONAL RESTAURANTS WORTH THE ROADTRIP

TOP CHEFS REVEAL THE ART OF PERFECTING YAKITORI

“We didn’t want any quarantine issues or to start a toad invasion in Tasmania. I think it’s too cold (for them to survive here), but you don’t want to risk it. I thought the collectors were going to lop off the legs, like you are supposed to, right away, skin them, soak them in salt water then freeze them and send them to us.

“But in fact they sent the whole dead frozen toads and the deadly venom in their glands had seeped all over the bodies, which made it extremely unappetising.”

After washing the toads, they were prepared to a recipe contributed by former chef and Arnhem Land tour guide David McMahon, who says they are delicious and “if you can’t beat them, eat them!”.

The thought of the toxins gave even the insatiably curious Kaechele pause, though.

“I consulted four websites (by cooks who) serve them all the time. They say only a fool would be afraid, it’s just a stigma. But meanwhile a scientist I spoke to at the University of Queensland said he wouldn’t eat them, and I included his warning just in case. People can make their own choices.”

Indeed, they can, and what fun it is to do so as you flick through Eat the Problem, a 544-page compendium of food and art that focuses on invasive species that accompanies a new performative exhibition at Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art.

The project is an epic labour of love for Kaechele, the wife of founder David Walsh.

Each recipe revolves around an invasive species that has wreaked havoc where it has been introduced.

Many, like the cane toad, were released intentionally but misguidedly.

Global warming has shifted others to new pastures with devastating consequences.

The contributors’ list is a star roll call of artists including James Turrell, Marina Abramovic, Matthew Barney and Salvador Dali and chefs including Heston Blumenthal, Tetsuya Wakuda (Tetsuya’s) Peter Gilmore of Quay and David Moyle (Longsong).

Some of them are dead, but in their lifetimes shared Kaechele’s fascination with unusual ingredients. None more so than wild Surrealist Dali, whose recipe here calls for 100 snails — one of his enduring symbols — and a bottle of Chablis.

Recipes in the cookbook range from shocking – think coal-roasted cat, sweet and sour cane-toad legs and fox curry – to less challenging game such as rabbit and venison.

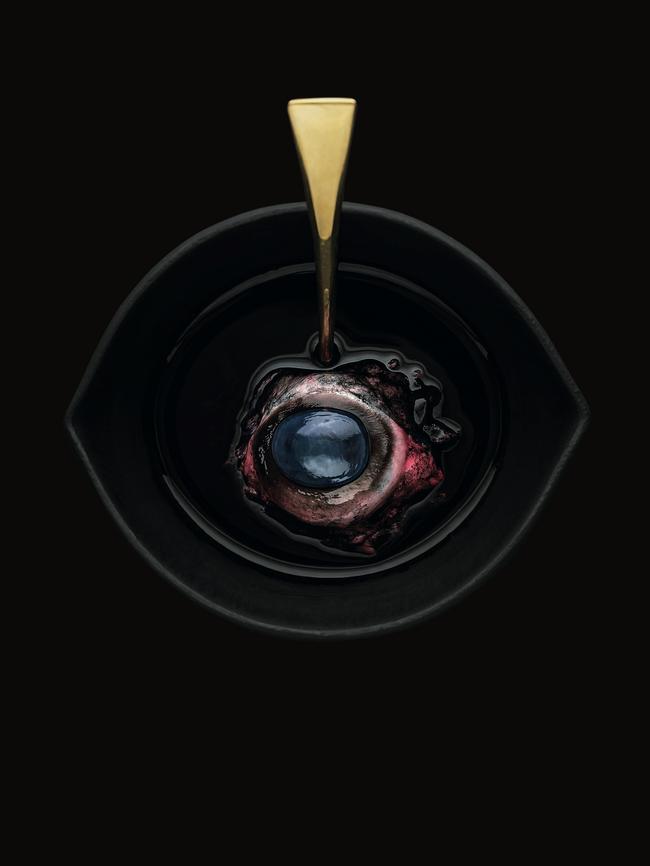

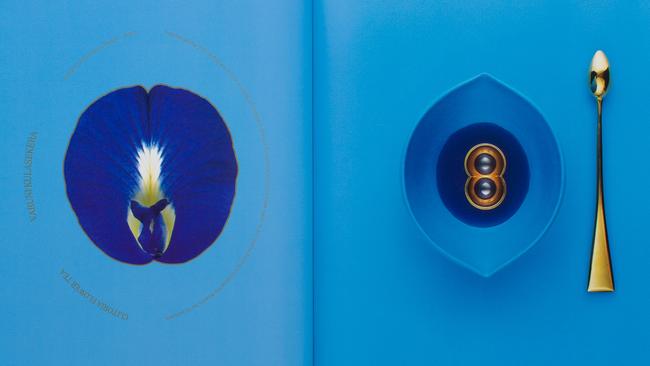

Are people actually meant to cook these crazy concoctions? The pristine white cloth dust jacket, which would last about two minutes before getting tomato-splotched in most kitchens, suggests the book is bound instead for coffee tables, where its environmental message is packaged with breathtakingly beautiful photography of the most bizarre offerings.

There is plenty of illuminating reading beyond recipes, with numerous essays, shorter pieces and interviews.

WEIRD AND WONDERFUL

Unlike most people’s creative projects, which are typically ambitious in conception and then scaled back as reality strikes, Kaechele’s book grew wilder as it progressed.

“It was always a rainbow, from the beginning,” she says of the multi-coloured stock on which key ingredients are matched to page hues. Think pink for buffalo tongue.

“It was more of a foodie bible to begin with. I was focusing on Tasmanian food in general, and celebrating terroir and foraging. It emphasised weeds and eating the problem, but included other ways of eating off the land in a meaningful way, too.

Then I realised that ‘eating the problem’ was much more fun and I should narrow it down to invasive species only.”

Clever, curious, iconoclastic and with a mesmerising manner magnified by her dreamy Californian lilt, Kaechele’s relationship with Mona founder, collector and philanthropist David Walsh, predates the 2011 opening of Australia’s biggest private museum. She has been an integral part of its activities from the start, often expressing herself through collaborations involving food, art and community development.

At grassroots level, these include her 24 Carrot food-growing program at schools in disadvantaged areas in Hobart and Heavy metal, an art-science project focused on mercury contamination in the River Derwent. At the high end are the spectacularly decadent performative feasts she conceives and directs as artworks in their own right, rejoicing with her husband in what they see as the rituals’ transformative powers.

“He feels great when he sees the apparitions,” she says.

“It is completely cathartic for both of us, and for everyone, really. I am very scientific, but there is a spiritual dimension to the feast. It’s choreographed, it’s a performance, and as a guest you become part of the work.”

Kaechele conceived their daughter Sunday after their lavish fertility-themed wedding feast in 2014. “The whole thing just symbolised soft, gorgeous femininity and was sublimely beautiful. It’s no wonder we had a girl,” she says.

She says the feasts she is planning to celebrate Eat the Problem and its accompanying exhibition will outdo even the wedding feast. “I think this one coming up is going to be even more powerful,” she says.

WILD ABOUT FOOD

She may talk up myna bird parfait washed down with a boar’s eye Bloody Mary, but Kaechele’s daily diet is quite tame, as it turns out. For the record, she didn’t eat the placenta after the birth of her only child, in 2015. And her husband is vegetarian.

“He doesn’t like to kill anything that has a mind,” she says. “And I say I don’t like to eat anything that I am not willing to kill, but I am very comfortable killing an oyster. Or a scallop. Or even sardines, though I feel a little bad about sardines. But I don’t like to eat tuna because I am not happy killing it. I can’t kill a tuna. They are too big.”

She doesn’t tend to eat red meat. “David and I both had a little bit of deer from our property just a few bites. If you are going to eat meat, that’s the sort of meat it makes sense to eat. So who knows, it could convert us.”

She is riled over restrictions in Tasmania that prevent wild-caught deer meat being sold in restaurants and is agitating for regulatory changes to venison sales. For now, it is served at Mona only at private functions.

There’s no fox on the menu, though, and not just because there are (apparently) no foxes in Tasmania.

“We have a fox recipe in the book, contributed by Englishman Fergus Drennan, but I am not that excited about fox meat. It sounds as if you are doing a lot of prepping and boiling of the meat, and you use a whole lot of spices to cover the flavour.”

She is convinced by fox fur, though.

“I mean, who isn’t?” she says, running her pale gold-ringed fingers over a foxy fashion spread in the book. “Look at that. Come on, that’s gorgeous!”

PEST AND LESS

She says the world has warmed to the notion of eating pests since she started working on the book five years ago. “Then it seemed like a radical idea to eat invasive species and now I think people are pretty ready for that. It’s not as confronting and it just seems to make sense.

“So many of the foods we view as pests are popular in another cuisine and part of a whole culture. It’s just that we didn’t evolve with that particular animal, so we don’t have a culinary tradition built around it.”

While the book is global in conception and content, Tasmania and its problematic introduced species are a strong presence. Sea urchin is well-covered and of particular concern to the author, with warming sea temperatures luring the long-spined urchin south from its native NSW, devastating the kelp forests and seaweed beds both in Port Phillip here and down in Tasmania.

Many chefs were keen to use sea urchins as their hero ingredient in Eat the Problem.

“That was the number one request because of the culinary potential,” she says, though some say the long-spined variety is unpalatably bitter.

“Every chef knows how delicious urchin is, it is divine. It’s a delicacy, and the Japanese have been celebrating it forever. They are desperate for it and it is overfished in Japanese waters.”

Invasive plants are a focus of the book, too, with Kaechele raving about Mona head chef Vince Trim’s dessert flavoured with the flowers of declared weed gorse. Vince was a key collaborator on the project, sharing and cooking not only his own recipes for photography but preparing many of those contributed.

With the book completed, Kaechele’s focus is now on feast preparations.

“It will be a living installation,” she says. “Guests will eat the rainbow, eat the problem course by course, each course in one colour, through a nine-course degustation.”

And what will Kaechele wear to the first of these epic feasts? A long majestic gown made from a patchwork of leather. Cane toad leather, of course.

Eat The Problem, an artwork by Kirsha Kaechele, Mona Publications, $277.77.

Next week, the Eat the Problem exhibition will open at Mona. Featuring a monumental vibraphone table, performance art and ritualistic eating implements, the exhibition explores the act and art of transformation and will accompanied by a series of feast events.

From April 13 until September 2.