Bourke St rampage survivors recall the horrors of that day and their long road back to recovery

JUST back from maternity leave, Nethra Krishnamurthy stepped out in the CBD to go breastfeed her baby. Seconds later the Bourke St rampage driver hit her, throwing her through the air and tearing her body apart.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- MUST-READ: Angel of Bourke St reunited with victim she saved

- IN-DEPTH: Police allegedly had three chances to ram Gargasoulas

- EDITORIAL: References to Bourke St now belong in a more innocent time

SHE remembers almost nothing after shutting her laptop at her work desk that day: the impact, the nurses, the operations.

For three weeks, nature and medicine shielded her from the shock that she was skittled by a car hurtling at up to 80kmh.

Her husband, who was by her side at the time, is not blessed with such amnesia and so their story is mostly his to tell.

Mohan Kumar and Nethra Krishnamurthy sit in their Bayswater living room, where balloons huddle after son Hari’s first birthday party.

Hari giggles in a final show before bed, a toy truck, complete with siren, in his sights.

Kumar is describing a routine catch-up on January 20.

He and his wife, both 33, work for different IT companies on neighbouring floors at 385 Bourke St. Both had a spare moment, he explains. He would grab a coffee.

Three days back from maternity leave, Krishnamurthy would breastfeed Hari at a daycare centre down the street.

Kumar does not recall much about meeting downstairs. Nothing seemed amiss: work was fine, Hari was happy. They smiled in greeting, he now thinks, but did not speak as they headed through the glass doors and down the building’s stairs.

A wall prevents line of sight east along Bourke St. Smokers normally gather near the taxi rank — if they gaped in surprise, the couple did not notice.

The first the pair knew of a dirty red car, and of bodies being flung like dolls, was when they stepped on to the footpath and the roar of twisted metal and shattered glass engulfed them.

Kumar jumped left and fell on to the road. His brain filled with images of Paris.

“Oh, my God, this is happening here,” he thought, as he braced for gun shots.

Krishnamurthy turned, or at least her injuries suggest she did.

Lifted 20m or more, she was reduced to another of the terrible thuds that marked the meeting of pedestrian and projectile.

Kumar almost shivers as he recalls each of these collisions not as a sound but a feeling.

Krishnamurthy bounced off the car, in a flight that grabbed the attention of Charlotte Galpin, 24, who works for a travel business across the road.

Krishnamurthy’s major organs ripped and punctured.

Six people died because of this 75-second car ride.

The injured could each claim one of the bollards that sprung up in Melbourne last month as a personal legacy.

Stunned police in pursuing cars later speak of people being hurled 20m into concrete — and getting up.

In assuming a death toll that would top 50, one of them speaks of the final figure as a “relief”.

Only when Kumar looked up did he wonder about his wife: their separation in these moments — his “choice”, not a choice at all — would bloom as guilt in counselling sessions.

His processes were condensed to a series of snapshots that belong in a movie sequence. Their clarity and vividness would curse him with insomnia.

He speaks like a narrator, softly and with sensitivity, of the details that haunt him.

His wife was a broken heap. Her eyes were open and unblinking. Her legs were unnaturally folded, in a pose he took for death.

Nearby, Jess Mudie, a 22-year-old “bright bubble of joy” from Sydney, was dying.

He wondered how a breastfeeding stop had come to this. How he would manage without his wife of nine years.

They had so many plans. They chose Melbourne over Brisbane and London. They had lived in the city and wandered the streets in the late hours, because it was friendly and safe.

A colleague tried to comfort him.

Kumar speaks of his behaviour as though observing another.

“I was screaming so loud I could hear my own voice down Bourke St”

“I can still visualise my screaming and everyone else absolutely silent.

“I have never screamed. It was a different world.”

Blood seeped from his wife’s head, which Galpin and another worker — both trained in first aid — swabbed with a scarf and cardigan.

They were calm, whereas he wailed and fell about.

Galpin, the former airline cabin staff, finally looked up. Krishnamurthy had squeezed her hand.

“Hang on, she’s still breathing,” she announced.

Here, Kumar’s shrieks quelled. His fears found a new home: death became permanent brain injury.

Paramedics arrived. They attached a drip and prepared a stretcher.

A pilot light sparked an instinctive urge in Krishnamurthy: she tried to rise, as if from the dead.

The ambulance ride was the longest journey. Past Mudie. Past Matthew Si, 33, who also died. Past the upturned pram.

“He seemed to drive slow because I was thinking fast,” Kumar says.

“I just wanted to get there.”

Kumar sat in the front: by trip’s end, the young ambo in the back was close to tears.

She had resisted Krishnamurthy’s jerking throughout.

It was too much. And it was only the beginning.

‘THE STAFF HUSHED WHEN THE FIRST PATIENT WAS WHEELED IN’

THE Alfred hospital emergency and trauma physician Helen Stergiou cannot recall the paramedics’ faces; instead she remembers their singular look.

The “different dimension” was not because the patients were “scoop and run”, as opposed to being anaesthetised and stabilised for transport. “They were in fear,” Stergiou says of the paramedics.

“Whatever they had seen had shaken them.”

Stergiou had had about 15 minutes to prepare, scrub up, call two family members (“Don’t go into the city”) and ponder gunshot wounds and the blunt trauma of “pedestrian versus car”.

She had been writing emails and speaking with the hospital’s director of trauma, Mark Fitzgerald.

When he called back, his voice was different: “Something’s happened at Bourke St.”

Now Krishnamurthy lay in a cubicle, her husband fretting beside her. Her heart was racing and her blood pressure was low.

An ultrasound showed fluid leaks in her abdomen.

She was too unstable for a CT scan, typical for most critical patients.

Krishnamurthy went from “A to Z” and was rushed to theatre for exploratory surgery. Her liver was lacerated, her intestines bruised and torn.

These injuries patched, she was given the CT scan, which revealed vertebrae fractures, a punctured lung and fractured ribs.

The good news was no brain bleeds. Her spinal cord was intact.

The bad news was more operations and a medically induced coma.

The next day, in talking to Krishnamurthy’s sister in India about a blood clot filter operation, Kumar broke down for the first time.

He had stayed composed in those first few hours at the hospital. Now he cried. And cried.

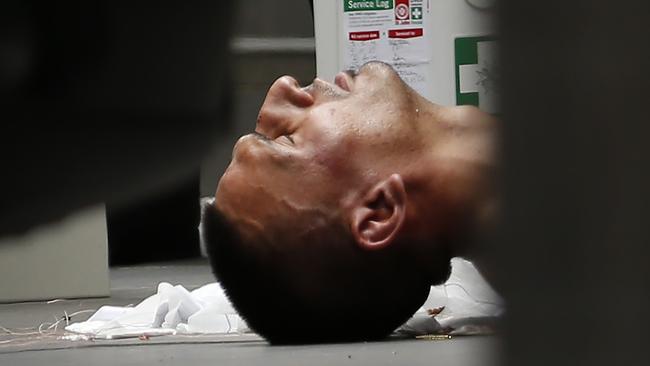

He didn’t know then that Dimitrious Gargasoulas, 26, had lain in another Alfred emergency ward cubicle, a blue curtain or two away from his wife.

He had bullet wounds to the shoulder and leg.

Gargasoulas would later be accused of driving the Holden Commodore on Bourke St. He would be charged with murder.

The rest of Melbourne is still unaware of Gargasoulas’s presence at the Alfred.

Another observer that night says the sheer number of police officers offered a clear indication that security was tight.

In the days that followed, reports suggested that Gargasoulas had been taken to either the Royal Melbourne Hospital or St Vincent’s.

He was brought to the most secure trauma bay at the Alfred, nicknamed the Bill Clinton Bay, after elaborate preparations for a presidential visit to Melbourne.

Fitzgerald did not want disruptions. He assigned senior staff should the management of the patient become vexed.

It is “very difficult”, he concedes, to secure controversial figures in the emergency room.

Reports swiftly linked the Bourke St car to kids and a baby.

Yet Fitzgerald waves off comparisons with the Royal Hobart Hospital experiences of Martin Bryant, the Port Arthur killer of 1996, and the observers at the time who still speak of staring contests.

He says his staff were “very careful” in treating Gargasoulas. Fitzgerald did much of the follow up himself. He wanted to avoid “subjective errors”.

“The staff were good,” he says.

“There was a lot of pressure to get him into a more secure facility and it was just a balance of when the medical staff were happy to shift him. That was the primary issue. It wasn’t really a conflict but people were just anxious having him here.”

Video shot by Fitzgerald shows 57 staff readied in the moments before the first patient — a woman fading fast — arrived.

Most had their arms crossed, as if in rumination.

Fitzgerald says the job demands acceptance — sometimes, you can’t know all the facts.

One doctor had received a panicked call from his wife, who was having coffee in Bourke St. Another doctor was on the second day of her medical career.

At the time, no one knew whether more incidents would follow and how many people were injured.

Like Fitzgerald, Stergiou is dry of humour and methodical of thought.

Along with angles, energy transmission and kinetic forces, she counts “dumb-arse luck” as a major factor in surviving major trauma.

She is a veteran of emergency rooms. Late on the night of Black Saturday, after she had treated a few dozen firefighters for burns, she was told (incorrectly) to expect 1000 patients.

On January 20, she naturally wondered — “How big will this be?”

Yet the waiting is also the “creative time” when doctors set to bringing order to the impending chaos.

Fitzgerald, who was receiving patients for the Kerang train crash in 2007 when he heard that his cousin and her two daughters were among the fatalities, was pleased with arrangements.

“OK, here we go,” he thought.

The staff hushed when the first patient was wheeled down the opening corridor.

Throughout the ward, bright lights cast dark shadows, which, typically for loved ones, offer shelters for hives of anxiety.

Visitors were cleared on January 20.

The trolley was wheeled past the control centre and the all-important “Bat Phone” and into one of the eight emergency cubicles.

“It was like a wave because of the geography of the department,” Stergiou says. “There was this parade of people and as this patient filtered through there was just a quiet.

“It was a bit unnatural. Whether it was people seeing the ambulance officers’ faces I don’t know.”

The third patient was Stergiou’s. Usually, such a list of injuries would demand 15 medical staff — today, Stergiou headed a team of four.

Studies show that problems arise in emergency medicine when — in simple terms — clinicians don’t do the right thing.

In resuscitation, a lifesaving decision must be made, on average, every 72 seconds for the first 30 minutes.

Stergiou speaks of loops, of going over and over the patient to detect concerns that may have been missed.

Her patient needed to be anaesthetised — once the woman called a loved one. The recollection chokes up Stergiou six months later.

“You just see how resilient human beings are,” she says.

“Wow.”

All seven Bourke St patients admitted to the Alfred had medically good outcomes.

Kumar became intrigued by a patient housed in a separate room inside intensive care, near the entrance.

This patient had a dedicated staff, which struck Kumar as preferential treatment.

“Is that him?” he asked a police officer at the hospital’s main reception area, referring to Gargasoulas.

“I was very stressed throughout those days,” Kumar says.

“That was the most upsetting thing, going in and out of ICU. It was hypothetical, because I wasn’t sure if it was him.

“I was confused and I was angry.”

‘EVERY TIME I CLOSE MY EYES, I CAN’T GET IT OUT OF MY HEAD’

STERGIOU calls it a “corridor consult”, though her chat with Kumar took place in an equipment room.

She thought he wanted to talk about his wife: it became clear he was consumed with anguish.

Kumar bent rules so that he could sleep in a chair by his wife’s bed.

He appointed himself an “assistant nurse” who carried out menial tasks. The joviality was a mask.

ICU nurse Melanie Tew points out that Kumar needed to “debrief”, too, about how “every time I close my eyes, I can’t get it out of my head”.

“He was suffering severe trauma in a situation where his resilience base was not huge,” Stergiou says.

“So unless we were able to offer support this could have continued and he could have dug himself into a deeper hole.”

Stergiou sent him for counselling. She had other advice, too. Bring in Hari. Now. It was five or so days since Krishnamurthy had seen her child. They needed to rebond.

From that time, Stergiou says, the patient seemed more serene.

Stergiou sees patients wallow and patients fight.

Krishnamurthy’s stoicism — expressed as a critically ill patient from her hospital bed as concern for the welfare of her husband — was “quite amazing”.

Romantics might call it a measure of love.

Kumar told his wife why she was in hospital. It was difficult: “Someone hit you. Six people died. You’re lucky to be a survivor.”

Because of her memory loss, Krishnamurthy asked the same question a dozen times or more. Kumar, in turn, repeated the same answer a dozen times or more.

‘FIVE YEARS AGO, NOT EVEN THAT, WE WOULD HAVE JUST RAMMED HIM’

KUMAR is more hands-on than some fathers. For one, he likes shopping for toddler clothes. That’s how he and Krishnamurthy spent the Saturday, at Eastland, before the Friday when Krishnamurthy was rushed to hospital for a two-month stay.

That same weekend, Gargasoulas was fighting for his freedom.

Police say on November 19, they attempted to pull him over on St Kilda Rd, but Gargasoulas was aware pursuing police would abort the chase.

“He would drive down the wrong side of St Kilda Rd at warp speed,’’ a source alleges.

That Saturday afternoon, January 14, a hearing was heard by a bail justice. Police believed that the outstanding warrants and the charges would keep Gargasoulas remanded.

Gargasoulas, representing himself, offered a short plea for freedom, arguing that he was not a flight risk.

Chief commissioner Graham Ashton has said that police opposed bail, as do sources close to the hearing.

One describes the decision to release Gargasoulas as “unbelievable”.

Yet conjecture surrounds the hearing. Official details are yet to be released.

The bail justice, Christos Pantelios, a schoolteacher, is said to have since claimed that he was wary of jailing Gargasoulas because of his police status.

It’s also been suggested that Gargasoulas could have been remanded and recommended for assessment under the Mental Health Act.

Pantelios is not speaking publicly, according to a public relations company acting on his behalf. It’s unclear who is funding Royce Communications to represent him.

It is believed that Gargasoulas’s bail was predicated on a court date for family matters the following Friday, January 20.

The day after the hearing, Gargasoulas allegedly turned up at the police station and announced that a comet would hit the Earth.

His attention-seeking behaviour had earned him a “smart-arse” label. Another time, he foisted Seventh Day Adventist pamphlets on officers.

The Sunday Herald Sun has learned that he allegedly ranted about being the “King of Kings”. Gargasoulas obsessed over a conspiracy theorists’ forum.

The website’s homepage promises “the source of all of the information that every single Living Soul on this Planet needs”.

The text is littered with bold, underlined and capped lettering, referenced from myriad religions.

Gargasoulas was considered a “nobody” with a huge ego, who allegedly became obsessed with a particular police officer in the days before Bourke St.

“What he was, you’d see 50 people walking around here with a similar mental state,” a well-placed source says.

Krishnamurthy worked at home Monday and Tuesday, in graduated steps for her return to work after more than seven months on maternity leave.

Meanwhile, Gargasoulas turned up at the St Kilda station again on the Monday or Tuesday. He was accused of assaulting his mother’s boyfriend on Wednesday and stealing his car, a red Holden Commodore.

Police started searching for Gargasoulas.

On Thursday night, Gargasoulas was accused of stabbing his brother in the face after an argument.

The following morning, after visiting known addresses, Gargasoulas is allegedly spotted driving on Punt Rd.

Police hatched plans to ram him at the corner of Toorak Rd and Chapel St. The car was blocked in. But permission to do so was not given.

“Five years ago, not even that, we would have just rammed him,” a police source says.

“But if we had done that and he just smashed into cars or injured a pedestrian because of us we would have been in trouble.”

Police trailed the car through Toorak to South Melbourne, where it sped away despite cars and pedestrians.

“He nearly knocked one of the pedestrians over trying to get away,” the source says.

Police allegedly got Gargasoulas on the phone. They wanted to bring him in peacefully.

“Give me some time to think, give me some time to think,” he’s thought to have said.

He allegedly offered to come in the following day.

He again spoke of comets. People must shelter in bunkers: “I’m the only one who knows about it.”

Gargasoulas allegedly drove to DFO at South Wharf, where a woman was released from the car.

A witness alleged that he evaded police by shunting other cars.

The civilian driver tells the Sunday Herald Sun that police officers stared at one another before a single car took off in pursuit.

In Yarraville, police moved to block the car — it again eluded the trap. On the phone, he allegedly sounded spooked by a police helicopter and wanted it gone.

Police were trying to phone and text him again as the car drove towards the city. He accelerated whenever the police neared.

No explicit threats had been made to harm others. Police backed off.

When a red Commodore started doing doughnuts at the corners of Flinders and Swanston streets, the driver was thought to be seeking attention.

The crowd mistook the spectacle as part of a nearby homeless protest: some protesters raised a finger to police who positioned themselves between the car and the crowds.

At work, Krishnamurthy had been nutting out an IT problem concerning the Bank of Queensland.

She now had time to pause, and told a child care worker that she was on her way.

This dreadful coincidence of timing — the imminent collision of wholesome intent and wilful carnage — troubles Kumar.

Why couldn’t he and his wife have left 385 Bourke St sooner or later? Ten seconds would have been enough.

Police activated their sirens when the car drove up Swanston St.

It’s said some police — never expecting what would happen next — welcomed this development, given the car seemed headed away from the city and crowds.

One source speaks of pursuing officers now being troubled by this course of events.

Stergiou, the doctor who tackles random misfortune for a living, wrestles with questions that may never be properly addressed in judicial forums.

Nevertheless, they are questions that Kumar and Krishnamurthy ask, as do so many other Melburnians.

“This is Bourke St Mall on a Friday,” Stergiou says.

“One month prior, a queue was waiting to see the Christmas windows. What the hell is going on?”

‘A LOT OF BAD IS HAPPENING BUT A LOT OF GOOD IS HAPPENING, TOO’

KUMAR wants to tell a tale in hope and generosity. To this end, his wife’s infectious laugh doubles as a cue for optimism.

“We are not denying the bad experiences, but we’ve had good experiences, too,” she says.

“A lot of bad is happening but a lot of good is happening, too.”

The couple is humbled by kindnesses they never expected.

Her company, Mexia Consulting, raised $150,000 in three days, mostly in anonymous donations. The couple is especially touched by this: the giving without expectation.

A work manager cooked meals, a neighbour cut the lawns, friends wet-nursed their son.

Good wishes on social media spurred them through dark nights.

They have thanked the two unsung angels who helped Krishnamurthy on the footpath.

Both women have, until now, shimmered offstage, one in a haze of Krishnamurthy’s memory of a hospital visit, the other — Charlotte Galpin — in the jags of Kumar’s emotions during a phone call of thanks.

They are the women who, as Kumar puts it, “saved my wife”.

On Friday, Galpin and Krishnamurthy hugged and held hands and made plans to catch up for lunch.

Kumar has returned to work as a UniSuper web developer. His immediate boss, Matt Shadwick, was at the Alfred in support in the hours after Bourke St.

He says Kumar is telling bad jokes — a good sign.

Quiet and smiling, Kumar is much as he was at work before January 20, despite the adversities. This week presents another milestone: Krishnamurthy returns to work.

Mexia has organised a custom chair and desk, to ease the fatigue and pain of her back injuries. Broken toes meant she could not walk unassisted until April. Holding Hari for long periods is exhausting.

Back at the Alfred in May to remove the blood clot filter, she ran into Stergiou as she was being wheeled from surgery.

Both women describe the encounter as they might a chance meeting of a lost school pal.

The process, from crutches, to walking frame, to protective boots, has been “quite a bit of a journey”.

The couple will stay in Melbourne, a place they know better than many born here.

They cannot forgive, they say, but they give little thought to the accused, who is remanded at Port Phillip Prison.

They peer at strangers on the street, wondering if they ought to be locked up, because the “justice system is not doing justice”.

“We used to love the city,” Kumar says. “But now we are scared of the city.”

They expect their love will bloom again for Melbourne.

The city is filled with generous and friendly people, and they still plan to raise children here. The difference now is that they always check the footpath for oncoming cars.