Andrew Rule: Murder, mystery and myth and death by misadventure

‘DEATH by misadventure’ doesn’t usually mean foul play. But there are some exceptions, writes Andrew Rule.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

VALENTINE’S Day isn’t all hearts and flowers. It marks the anniversary of one of the infamous underworld massacres of the 20th century — seven men were shot dead in Al Capone’s Chicago in 1929 by rival gangsters.

In Australia, Valentine’s Day is linked in our minds with the “disappearance” of picnickers at Hanging Rock, a story made indelible by a haunting film based on a clever book.

BARWON PRISON BOSS DAVID PRIDEAUX DECLARED DEAD AFTER VANISHING AT MT STIRLING IN 2011

MISSING BUSHWALKER WARREN MEYER MAY HAVE BEEN MURDERED BY DOPE DEALERS

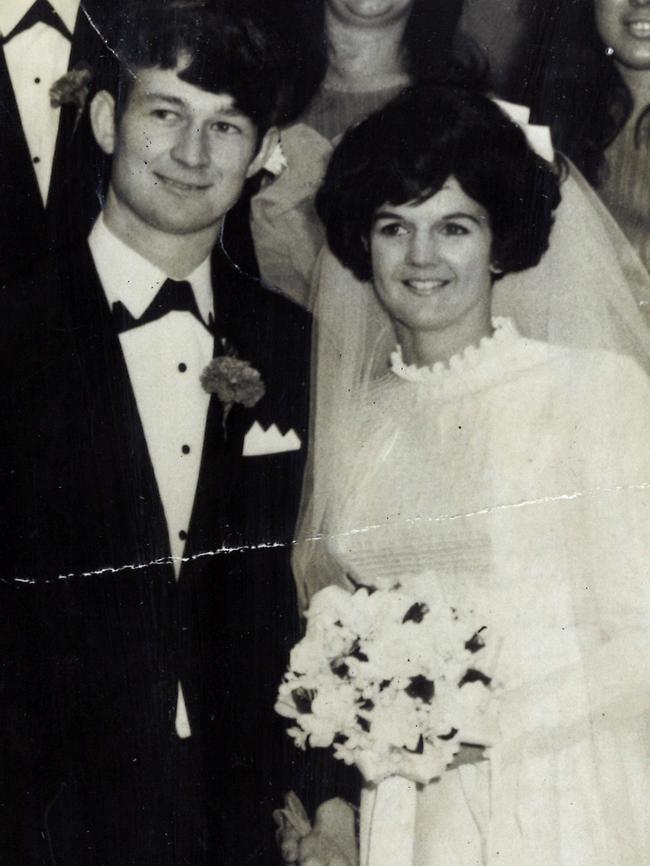

On Valentine’s Day, 1975, a film crew had just finished shooting Picnic at Hanging Rock on location northwest of Melbourne. The same day, in North Balwyn, a 27-year-old nurse named Helen Barr was preparing for a romantic picnic next day at Lake Eildon.

Picnic at Hanging Rock would become an Australian classic, its spooky mix of realism and fantasy persuading us it was based on an actual event: the supposed disappearance of three schoolgirls and their teacher on Valentine’s Day, 1900.

Most Australians of the era got to see the film. But Helen and her husband Doug Barr never did. They disappeared the next day.

The Hanging Rock myth is part of popular culture but the true story of how a suburban couple never returned from a country picnic has been forgotten except by those who knew them.

That Saturday, the Barrs drove to Lake Eildon with their samoyed dog in their white Mini. They put a picnic rug near the “race” of cold water released from the dam wall into a pondage feeding the Goulburn River.

What happened next, no one can prove, but it seems clear at least one of the Barrs went in the water, ignoring signs banning swimming — this because of the danger of ultra-cold water being released at intervals from the dam wall. In between releases, the water race and pondage looked deceptively safe.

At dawn next day, a local angler, Frank Burbury, saw the empty Mini, dew on its windows indicating it had been there overnight. He noticed a man in a maroon jumper nearby.

Soon after, another Sunday fisherman, Scott Henderson, saw the car and the dog sitting on the rug near the water. When he returned later the dog was running between the car and the water.

Another angler, Eric Elliott, saw the distressed dog and the Mini and told the local policeman, Sgt Max Moate, who noted that the Barrs’ clothes were scattered around the spot as if they had changed for swimming.

Doug Barr’s wallet and keys were missing, which seemed to add a layer of mystery. But a couple of likely scenarios could explain that.

The most obvious is that Barr (not a keen swimmer) had the keys (and perhaps the wallet) in his shorts pocket and had jumped into the water to help his wife after a surge of lethally cold water discharged from the dam wall swept her off her feet.

Another logical explanation for the wallet’s absence is that someone (the man in the maroon jumper, never found) had taken it early that morning. Such casual thefts happen every day.

The longer the search went with no sign of the Barrs, alive or dead, the more speculation mounted. It seemed unlikely they got lost in nearby bush, given that the dog would have followed them. But because there was no concrete proof of drowning, some theorised they had staged their own disappearance — or had been abducted.

Unlikely as the alternatives were, family and friends did not want to believe the couple had simply drowned. They insisted police treat it as a crime.

A reward was posted and dozens of fruitless “leads” investigated, mainly to satisfy relatives. Police privately believed that suspicions of foul play rested on two mistaken assumptions — that drowned bodies always float and that bodies could not escape from the Eildon pondage into the Goulburn River.

One policeman reflected later: “It’s important to appease those who might criticise you. Dead people don’t lay complaints, but their relatives do.” The fact was, even if the bodies had stayed in the pondage there was no guarantee of finding them. Bodies in extremely cold fresh water — as in alpine areas — tend not to float as they do in warmer coastal waters, because they do not putrefy and create gas.

Then there is the “yabby factor”: if yabbies (or fish) pierce the stomach, a body will not float. They strip it to bare bones, soon buried in silt.

But family and friends of the Barrs still clung to the hope that if they hadn’t been drowned or murdered they might still be alive.

In a sense, the Barr mystery is no closer to a definitive resolution than it was that summer 42 years ago. But ignore the threadbare hope that love clings to when logic says there is none, and it seems certain they drowned the way people do every summer.

The Eildon mystery is one case of many in which the missing are never found. The fact a logical answer can’t be proven beyond doubt leaves a vacuum for speculation, gossip and fear. Rumours breed. And people who should know better can start repeating them.

The bizarre and often vicious speculation surrounding the fate of Azaria Chamberlain in 1980 is a prime example. Jaidyn Leskie’s disappearance in 1997 was another. Until Jaidyn’s body was found six months after he went missing in Moe, oddball theories ran wild — all of them muddying the fact that “babysitter” Greg Domaszewicz had been the last to see the little boy alive and was the police’s only suspect.

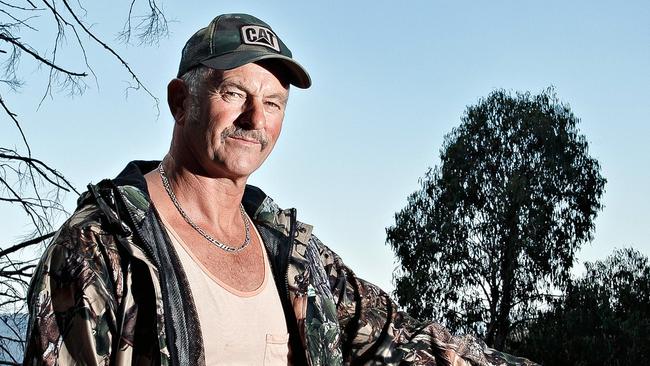

The babbling of bigots and gossips — some of it amplified by the media — can take over some cases. The best and worst example of that since the Chamberlain debacle was when Barwon Prison manager David Prideaux went missing while deer shooting near Mansfield in the winter of 2011.

Because this happened six weeks after high-profile prisoner Carl Williams was killed at Barwon, people who should know better traded jailhouse scuttlebutt that the disappearance was sinister rather than tragic. The conspiracy theorists suggested the respected senior public servant was either murdered (in “revenge”) or staged his own disappearance because of fear or because he had a secret lover. Take your pick.

Loonies, encouraged by cynical reporters and naive broadcasters who should be ashamed, told each other Prideaux “must have been” implicated in Carl Williams’ death. Why? Because, you know, it happened the same year.

Ignoring the likelihood the prison boss simply got lost or hurt and perished in the bush is almost up there with thinking Harold Holt defected in a Chinese submarine.

The fact is people go missing in the mountains, especially when it’s cold. They can die. Sometimes they’re never found. When a state minister, Tim Holding, got bushed in the high country in 2009, he’s lucky he was found. Add an injury and a cold night or two and he could have become another tragedy.

Such as when seasoned bushwalker and skier Stephen Crean — brother of former Opposition leader Simon Crean — disappeared in the snow country in 1985.

What was left of him wasn’t found for 18 months, and even that was only because some dill stumbled over his skull and took it home for laughs. If that fluke hadn’t happened, would we assume the missing man was the victim of a conspiracy?

It’s simple. If you die in the mountains, the wild dogs eat you and other animals and birds scatter the bones. Die in cold mountain water and your body doesn’t float and yabbies and fish do the rest.

That’s not to say there are no tragedies with sinister overtones. Occasionally “misadventure” does turn out to be murder.

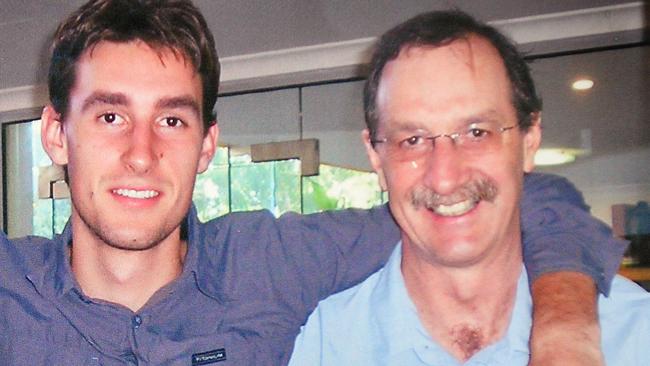

When bushwalker Warren Meyer did not return from a walk near Mt Dom Dom in 2008, police assumed he had got lost or ill and died. But his family never believed it — and offered a $100,000 reward for information. In 2014 an anonymous caller told police the missing man had been killed and buried. This matched the fact the Meyer family had found a commercial-size marijuana crop while searching the area in 2009, and that semi-automatic gunfire was heard there the morning Warren went missing.

The caller told police he had known about the murder for two years. The family of the man responsible owned an earthmoving business, he said. Tragically, there’s a conspiracy that makes sense.