Andrew Rule: Despite his life chasing colourful company, Geoffrey Edelsten died alone

Despite the caricature he defiantly maintained, those who knew Geoffrey Edelsten paint a picture of a complex man whose private persona clashed with his public image.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For a man who spent most of his adult life chasing fame and friends, Geoffrey Edelsten died not only alone but lonely. In his declining months, it seems, it was mostly paid domestic staff who had contact with him.

It was his cleaner who found him in his St Kilda Rd apartment on Friday just before the Swans took to the field against Hawthorn in Sydney, the city where Edelsten made his name in the 1980s and lost it in the 1990s before re-emerging as an increasingly eccentric figure.

In the end, says a neighbour who knew him most of his life, he was a recluse — a shrunken figure who still wore outrageous clothes rather than conform.

Geoffrey Walter Edelsten was, to echo the title of his 2011 autobiography, an enigma even to those who knew him: a man of many parts, some of them admirable but overshadowed by an exhibitionist streak and thirst for publicity.

The Edelsten taste for the trashy and flashy and conspicuous consumption became shorthand for 1980s Sydney crassness — a reputation he never lived down but reinforced as he grew more ostentatious in choice of clothes and (much younger) women.

But the ageing man in the canary yellow suits, dyed hair and string of busty escorts and brief marriages was a long way from the brilliant medical student whose name is on the venerated Prosector honour board in the University of Melbourne’s medical faculty.

To be Prosector of Anatomy at Melbourne is a much older distinction than to be a Brownlow Medalist — and rarer, in the sense that no one gets on the honour board twice. Either you top your year or you don’t. No runners-up.

As a current professor who is at the top of his medical specialty said yesterday, “I was no slouch but I didn’t get on the board and neither did a lot of other people who have done well. But Geoffrey Edelsten did.”

The professor didn’t know Edelsten personally but those who did paint a picture of a complex man whose private persona clashed with the public caricature he’d helped create and defiantly maintained.

Edelsten was born in Carlton in 1943 to Jewish immigrant parents, Hymie and Esther, Holocaust refugees who ran one of Melbourne’s first lingerie stores.

An amateur psychologist might wonder whether early images of lingerie models lingered in the memory of the boy who would grow up to marry, belatedly, a series of larger-than-life women all of whom might have been described as models at some stage.

The young Geoffrey Edelsten was always one of the smartest in any room. But the wider public did not hear of him until he was in his 40s, making his audacious bid for what was then still the transplanted South Melbourne Football Club, struggling to survive after a desperate decision to take the team north.

In the 1982 season, the players lived in Melbourne and played in Sydney. Tony Morwood, who played for the Swans then and would become a respected club executive, recalls how hard it was to get traction in a rugby league city where the winter sun shone so much that most people had alternatives to the footy.

At first, Morwood was one of the club stalwarts against the move. He later came to see it was the Swans’ only chance of survival if corporate sponsors and government would not fund vast improvements to its old home at the Lakeside Oval. Not all the old Melbourne VFL clubs could survive and “South” and Fitzroy were on top of the list of basket cases.

In 1983 and 1984, it looked as if the transplant was a success but the patient was dying. The Swans might as well have been a lacrosse team for all that Sydneysiders cared, apart from loyal Bloods fans who flew in for games and other southerners who happened to live in Sydney and missed real footy.

The Swans were running out of oxygen when an unknown medical entrepreneur stepped in.

No one outside medicine knew much about Dr G.W. Edelsten but his CV was already remarkable enough. As a star medical student in 1966, he had been credited with co-writing the songs “I Can’t Stop Loving You, Baby” and “A Woman Of Gradual Decline” for a local group.

He also owned a record company, Hit Productions, which worked for the growing music publishers Festival Records. In 1968, he co-produced the single “Love Machine” for the studio group Pastoral Symphony, comprising Glenn Shorrock and the Twilights, Ronnie Charles of the Groop and others.

It was the sort of background that might have led the entrepreneurial young doctor to ditch medicine and concentrate on a growing music scene that fostered contemporaries like the young Michael Gudinski and Ian “Molly” Meldrum.

Instead, Edelsten found a way to blend his medical skills with his entrepreneur’s instincts and flair.

A prodigiously hard worker who jammed two work days into every 24 hours, he managed to be a resident medical officer at the Royal Melbourne Hospital then to become a GP while managing his music industry interests.

He saw an opportunity in outback medical practices in rural Queensland and New South Wales, buying his first practice in Walgett. He learned to fly so he could provide medical care to remote communities.

In 1969, his third year out of university, he and a friend set up a new practice in Coogee in Sydney. After training an assistant to maintain the Walgett practice, Edelsten concentrated on expanding their Sydney toehold.

In 1971, just 10 years after leaving school, Edelsten (and Tom Wenkart) launched Preventicare, which did diagnostic tests and streamlined the way doctors handled medical records by using new American equipment.

Preventicare hit financial trouble in mid-1971 but by 1975, under a new name, Morlea Pathology Services, it was raking in huge annual profits. Edelsen, meanwhile, opened eight practices in Sydney and worked in Los Angeles for a couple of years, an exposure to Hollywood glitz that seemed to heighten his already acute showbiz instincts.

It was the Hawke government’s Medicare scheme in 1984 that turned Edelsten from workaholic doctor to medical tycoon. He set up revolutionary 24-hour medical centres which were, famously, decorated with chandeliers, white grand pianos and mink-covered examination tables.

Call it the Liberace touch. If the idea was to attract media attention, and therefore patients, it worked. An influx of 2000 patients a week, all bulk-billed, brought in rivers of gold.

By late 1984, Edelsten was going as well as the Swans were going badly. Opportunist by nature, he saw his chance to do something as daring in professional sport as he had with the hidebound medical profession.

He was, says a key man in that period and that process, Brian Ward, what is now called “a disrupter”.

Ward, a gun lawyer well-known in VFL circles, was holidaying at Lorne when a policeman knocked on the door to say that someone called Jim McKay was calling the police station desperate to get in touch with him.

There was no telephone in the holiday shack and Ward went off and called McKay, who was the VFL’s marketing guru. McKay told him that some “doctor impresario” wanted to take over the Sydney Swans.

It was a radical proposal unknown in Australian sport but the Swans were in such a bad way that no one was willing to reject the rich doctor out of hand.

The sure-footed Ward agreed to make a list of what was needed to make the buyout offer a credible option for the club. With his discipline and Edelsten’s instinct for promotion and publicity, the bid was accepted ahead of a proposal from another consortium.

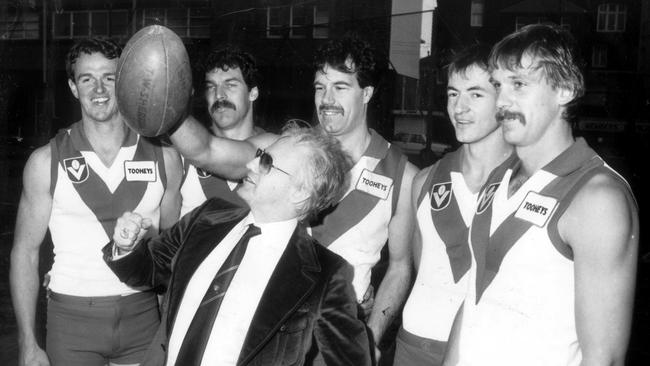

What happened next is sports history. Edelsten opened his cheque book and told the club to recruit the best available talent. They couldn’t get the rising star coach, Kevin Sheedy, but Sheedy told them to grab his mentor, the veteran Tom Hafey.

It was, recalls Hafey’s widow Maureen, a great encore for the grand old man of coaching. Given his choice of players to recruit, Hafey got the likes of “Diesel” Williams and Gerard Healy and made the Swans competitive on the field.

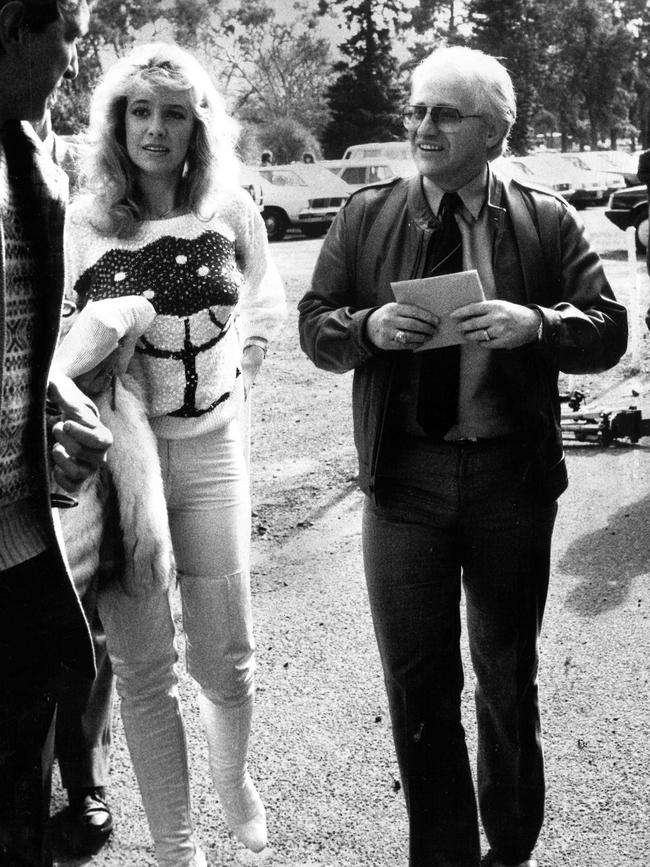

Meanwhile, off the field, Edelsten caught the attention of the fickle Sydney sporting crowd. In a city where what school you went to mattered less than how much money you had, the spectacle of the 40-something tycoon marrying a 23-year-old beauty, Leanne Nisbett, and showering her with luxury cars and a “pink helicopter” dominated front pages and news bulletins.

Morwood the intelligent player saw that the publicity explosion had done something pure football talent could not: “It took it from a football game to entertainment.”

In Sydney that mattered. So did winning.

Edelsen’s ownership of the club soon came unstuck, but the Swans did not. As Brian Ward mused yesterday, apart from anything else Edelsten did, the foundation he laid meant the first interstate AFL team flourished and allowed the league to become “the commercial behemoth it is today.”

By 1990, the Swans were part of the Sydney sporting landscape, the opera house motif on the “Bloods” guernsey the legacy of Edelsten’s instinct for the right branding.

By then, Edelsten was on the nose. He had lost his medical registration in NSW and would later lose it in Victoria.

Worst of all, in 1990 he was convicted of perverting the course of justice after a police telephone tap revealed he’d discussed using hit man Christopher Dale Flannery to assault a former patient. The obliging Edelsten had also provided Flannery with a medical certificate stating he was unfit to stand trial because of an infection.

He was jailed for a year. How that affected his business career is hard to know. He made and lost huge money in various ventures afterwards and made ever more grandiose gestures to capture publicity. The $3 million wedding to young American woman Brynne Gordon at Crown Casino in 2009 was either a new high or a new low, according to taste.

The public Edelsten was verging on a figure of fun, the sort of person Jay Gatsby might have become if he had become old and ugly instead of being shot dead in his prime.

Privately, say those who knew him, he was quietly spoken, polite, and good company. He was highly intelligent, both a good listener and a good story teller. And he had wide-ranging interests.

He had, says Ward, “what Leonardo da Vinci called an inquiring mind.” He was also stoic. When another doctor made a mistake that cost him one eye, Edelsten was not bitter about it.

Ward ran into him in recent years in a dentist’s waiting room for the first time since Edelsten swan song in Sydney.

“Geoffrey greeted me warmly and said ‘They were great days, weren’t they?’”