Alfred Health docs give hope to upper limb amputees with Aussie first prosthetic surgery

EXCLUSIVE: ALAN Newey lost his arm in a horror workplace accident 17 years ago. He is now lucky enough to be the first Australian fitted with a mind-controlled prosthetic limb. WATCH THE VIDEO.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ALAN Newey was five minutes into his shift when he started adjusting the conveyor belt at the manufacturing plant.

The then 35-year-old did the job that way he had been shown how — the dangerous way — putting his hands between the moist rollers and throwing drying dust.

As he started sprinkling, he felt a bang and heard a knocking noise in the machine.

Mr Newey started walking along the conveyor belt to find out where the noise was coming from.

“I went to scratch my head and there was nothing there to scratch it with,” he said.

“The noise was my arm going around in the machine. It was so fast.”

Now, 17 years on, the Melbourne man is the first to be fitted with a mind-controlled bionic arm in Australia.

The 53-year hopes the radical surgery performed by The Alfred Hospital’s osseointegration and Targeted Muscle reinnervation (TMR) unit, will help rebuild him to be the man he was before the accident.

“They could never know how grateful I am to be chosen as the first person for this,” Mr Newey said.

“I want to do my shoelaces up again. I want to contribute more around the house and not have to ask for help. I want to go to a dance and hold my wife Kathy properly. I want to go to the movies and hold both the popcorn and my wife’s hand.

“It’s the little things we used to do together that you miss.”

The new TMR surgical procedure reassigns nerves in what is left of the amputated arm, to target muscles that no longer have a purpose following amputation.

These transported nerves, which once controlled the arm and hand, then grow into these muscles.

The muscle helps amplify the electrical signals from the nerves about 1000-fold, so they can be recorded by electrodes on top of the skin to control a prosthesis through “intuition”.

“The signals sent from the brain to move a limb, continue to be sent even after amputation,” said The Alfred’s Director of Plastics, Hand and Faciomaxillary Surgery Frank Bruscino-Raiola.

“TMR allows this neural information needed to move the arm and hand to be accessible again.”

Six months after losing his right arm above the elbow in 1999, Mr Newey got his first prosthetic arm. It was a hook.

“It was terrible. The work you had to do to use it, actually put you off using it,” he said.

Next was a myoelectric arm controlled with electrical signals generated by his remaining muscles.

If he flexed his bicep, it would bring his arm down and close his hand. A tricep flex would raise and open it. It was more functional, but clunky.

“It could turn 360 degrees at the hand, so I could mix my wife’s girlfriends’ drinks. I still had a purpose,” he said.

“If someone is holding your hand and pulls on it, the muscles would react and instantly close thinking you’ve grabbed something. I nearly broke my mother’s fingers one day.”

MORE BRIDGID O’CONNEL:

HOW IN-WOMB BLOOD TRANSFUSIONS HELPED SAVE LEO’S LIFE

STUDY PROBES HEALTH IMPACT OF CHILDREN’S LIFESTYLES

‘GROUNDBREAKING’ RESEARCH GIVES HOPE TO STROKE PATIENTS

DIABETES PATIENTS AT INCREASED RISK OF HEART ATTACK AND STROKE

The idea of TMR was first raised with Mr Newey just over two years ago, after Mr Bruscino-Raiola and Steven Gray, director of the osseointegration and TMR program, returned from training with the procedure’s Chicago inventors.

“They asked me to go home and think about whether I’d take part,” Mr Newey said.

“I said; ‘I don’t need to think.’ I knew it would give me real improvements in my lifestyle.”

To ensure the prosthetic limb would snugly and reliably attach to his remaining arm, Mr Newey underwent osseointegration surgery. A titanium implant metal rod was inserted into the bone of the amputated stump for the prosthesis to connect onto.

Mr Newey is only one of a few patients worldwide to have the combined TMR and osseointegration surgery.

After these surgeries in 2015, Mr Newey needed to weight train, ready to hold the 3kg arm.

The nerve surgery would be useless if his shoulder was not strong enough to lift the device.

Each week he would add another 50g-100g weight disk onto the metal rod.

Each morning he would push the bolt down on a weights scale, holding for 20 seconds at 10kg of pressure, to further strengthen the bone.

The surgical technique for TMR is not new but the application is cutting edge.

When an arm is amputated the nerves that are left behind still carry the brain’s signals that used to control the muscles, and actions of the arm and hand.

But these nerves lose their intended target once the muscles lost in the amputation.

“TMR redirects these unused nerves to new small muscle targets,” Mr Bruscino-Raiola said.

“When these small muscles contract they generate an electrical signal that gets picked up by surface electrode which creates the prosthetic arm to move.”

The surgery on August 10, saw Mr Bruscino-Raiola and his team rewire three nerves into three small muscles to create three new signals to drive the prosthetic arm.

Two days after the eight hour surgery, Mr Newey starts feeling tingling in the areas over the muscles receiving the new nerve signals.

He can feel electrical shocks in the stump and in the phantom arm, down into his amputated palm and little finger.

“They want to give me stronger meds to dull this, but this is proof to me that it’s working; that the nerves are firing, that they’re alive,” Mr Newey said.

It’s a promising sign.

Come late November, more than three months after the surgery, the wounds have healed, his muscles strong and Mr Newey is ready to start the brain training.

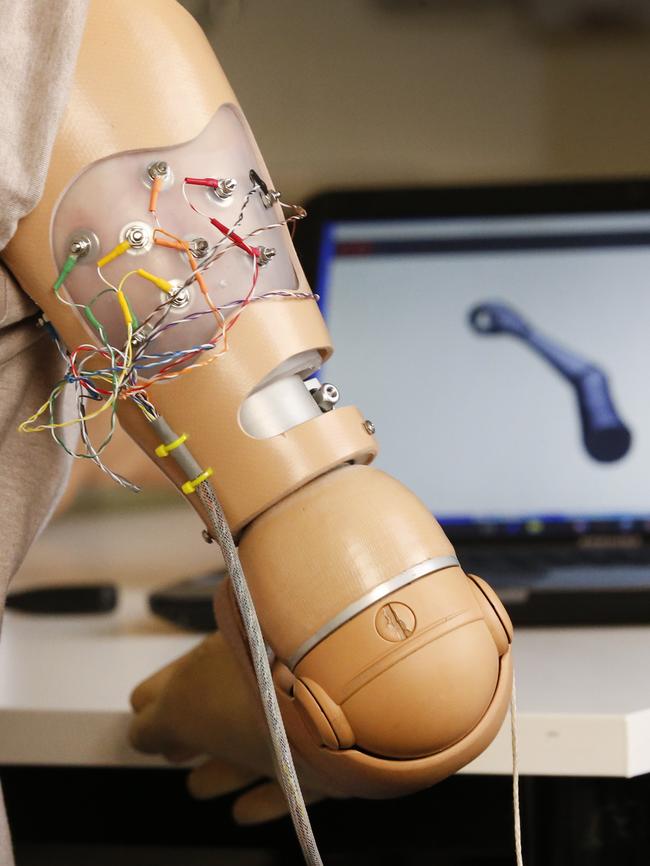

The 17 electrodes inside the arm socket pick up patterns of muscles signals from inside the arm.

“It’s the best on the market, commercially. It’s the closest you’ll get to a real hand,” said prosthetist David Lee Gow, who built the arm using parts from Germany, Sweden and the US.

Over the next six months he will undergo training with a prototype arm at the Epworth Hospital.

Mr Newey thinks about copying the movement of the animated arm on the computer screen.

It’s a slow process as the new nerves and muscles get stronger every day.

But already — through much practice — the device is learning the unique patterns of muscle activity produced when Mr Newey thinks about a certain task, and allowing the arm to move.

It’s incredible to watch, given these are actions he hasn’t needed or used in 17 years.

The aim is for him to have as many natural actions as possible after 12 months of training.

Since Mr Newey’s surgery, the Alfred team has performed the combination surgery on another seven patients, including one who lost both arms.

Four have already been fitted with their arms.

The service includes the surgery, rehabilitation and long-term follow-up to track outcomes.

“Advanced prosthetic limbs have been around for a very long time,” Mr Gray said.

“Two of the major problems have been attachment and control. The combination of osseointegration and TMR solves those problems.”

Mr Newey, who had the arm fitted this month, continues to work as an occupational workplace safety speaker.

He tours mines, factories and construction sites with a suitcase of prosthetic arms.

While he shares warning stories from his past, he is already looking ahead to the future; a bionic arm that allow you to feel the sensation of touch.

It’s already being tested in patients overseas.

“Initially after the accident I would hide my arm. Now it’s like a fashion statement. You put it out there and people accept you for who you are,” he said.

“You hear about things that could happen in the future, and you want to be the first to try it.”