After the flame: The village Melbourne forgot

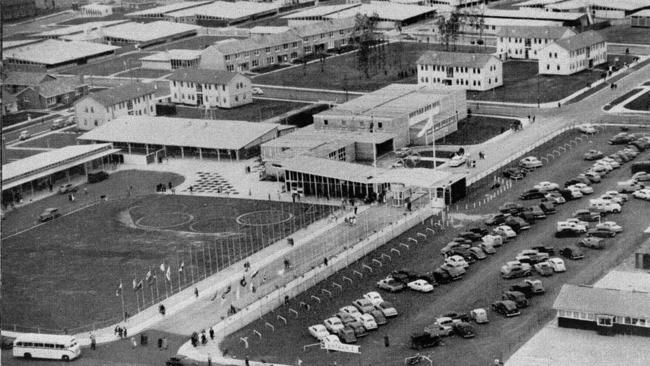

FOR two weeks in 1956 it housed 5000 world athletes. But for nearly 60 years since, Heidelberg West’s troubled Olympic village has been home to some of Melbourne’s most disadvantaged people.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE Ghetto. The Bronx. Heidel-burglary. The Olympic village, 10km northeast of Melbourne’s CBD, has been called it all.

It’s almost impossible to believe that this now forlorn area was once a showpiece mini-suburb.

It helped secure our reputation as a vibrant international city hosting Australia’s first Olympics.

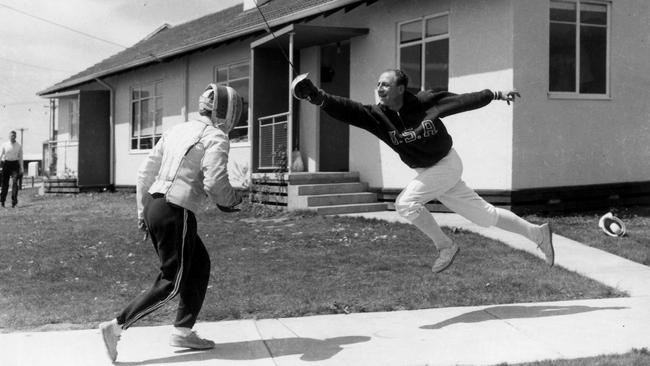

In 1956 it was home to almost 5000 of the world’s top athletes from 72 nations.

The Heidelberg West village was a beacon of national pride, and where the medal-laden careers of such homegrown Olympics heroes as Dawn Fraser, Murray Rose and Betty Cuthbert began.

But almost 60 years on, these once safe and happy streets are now mean streets.

Night — or day — you don’t want to find yourself here alone. Today, the only reminder of the jubilant history is the colourful interlocking rings welcoming those who dare to enter.

Now one of Melbourne’s most disadvantaged locations, a drive through the streets of the Olympic village is met with black burnout marks swerving up the tarmac, graffiti-riddled fences, unkempt gardens, and the occasional torn-up lounge or shopping trolley on the kerb.

The village — bounded by Liberty Pde, Dougharty Rd, Oriel Rd and Southern Rd — was designed as a series of 841 dwellings.

After the games, about 600 homes were allocated to the housing commission. Others were auctioned. It went downhill fast. In this special Sunday Herald Sun investigation, residents have told of brazen night-time robberies, wild neighbour disputes, domestic violence and parks littered with discarded syringes and broken glass. And in total, an area where the crime rate has doubled in the past decade.

Like many localities across the state, the deadly drug ice is not helping, locals say.

Teens huddle in the park late at night awaiting their next hit. Others linger in laneways to get boozed before leaving behind smashed bottles, takeaway food containers and the ever-strong stench of urine.

A local woman offers sexual favours behind a bush near the shops for a cigarette. These are all horror stories told by residents.

Some are so afraid they have splashed out on security cameras that sit very visibly on their porches, in an attempt to deter would-be intruders.

Others have boarded up their windows to keep the criminals out.

“People don’t realise what goes on here,” says Robert, who didn’t want us to publish his surname.

“More or less you have to have the blinds down all of the time. You get all the druggies hanging around in the park. There’s always swearing and carrying on.”

A burly bloke with tattoos covering both his arms, Robert says he has always been “a Heidelberger”.

But he has only been in his public housing unit near the Olympic village shops for three years.

And he wants out.

The 50-year-old says he has applied to be moved to other public housing.

His friends refuse to visit him because of safety fears.

“I’m sick of having to pick up syringes and broken glass at the front of my place, and walking out and seeing all this graffiti everywhere,” he said.

“As quickly as the council paint over it, these idiots are back tagging again.

“I always say if I catch them, I’ll give them a bloody kick up the a---.”

Asked what the inside of the accommodation was like he said: “It’s all right.”

But the reality is, for Robert, it is better than the days he spent sleeping on the streets. “I need somewhere to park my head for the night and this is what the ministry gave me,” he said.

ROBERT’S story is all too depressingly familiar in the village. He is one of about 2000 people who have fallen on tough times and are housed in the dilapidated, red brick taxpayer-funded lodging.

After the medals were awarded, and the competitors went home, the village became Victoria’s largest housing estate where impoverished and desperate tenants were placed with little support.

It became known as one of Melbourne’s most violent areas. Local welfare workers say many of the its problems stem from residents’ isolation, lack of education, unemployment and the integration of ethnic groups.

Crime escalated in the area in the 2000s, forcing police to set up the Olympic Taskforce.

The unit no longer exists, but Heidelberg police try to keep a visible presence with targeted patrols of the area as often as they can, particularly at night.

Residents, traders, police and the local Banyule council are working together to improve what some say has become a national shame.

Most say they are winning the uphill battle. But crime statistics indicate it is still a problem.

In the 12 months to March this year, 741 offences were reported in the Olympic village — averaging about two a day and more than double the 366 offences reported in the same period in 2005.

More than half (468) were property and deception offences, and 122 were crimes against the person.

Surprisingly, just 39 were drug offences — four times higher than a decade ago.

Despite statistics showing a rise in crime, Banyule Inspector Anne Pattison says the area has improved greatly in the past decade. “From all accounts of what I hear, it is much quieter than what it used to be,” Insp Pattison says.

“Obviously the area still has some challenging people in it. We still have dedicated patrols to provide a visible police presence which aim to deter and detect crime.

“We still have our crime prevention office and youth resource office who work in that area. And we are still involved in council and steering committee meetings to improve the area where we can.” But she admits: “There’s still a lot more work to be done.”

IT’S 6pm on a Friday, and Constable David Giulieri and Sen-Constable Melissa McCarthy have logged on for the night. They are assigned to serve and protect the Olympic village on their eight-hour shift.

Constable Giulieri said he didn’t even know the village existed before he was deployed to Heidelberg police station a year ago.

“I looked up a bit of the history of the area before I came and I was quite surprised,” he said. “It certainly was the pride of Melbourne back in the day.”

When the first job comes over the radio within 15 minutes of signing on, Sen-Constable McCarthy remarks that’s “usually the sign of a busy night”.

The officers head to a house where a woman armed with a knife was threatening her neighbour. They are met by a hysterical woman who locked herself in her home and refused to come out.

After about an hour of negotiations, the woman emerges through the front door. She is assessed and the Crisis Assessment and Treatment Team (CATT) is called in. The woman is taken to hospital. The police officers’ job here is done. For now.

The next stop is the shops on the corner of Alamein and Southern roads. But chats with the owners reveal it has been a quiet night with no troubling customers.

A stroll through the park where residents earlier told of regular anti-social behaviour unveiled silence.

No one was even lingering in the nearby laneway.

The officers scan through a folder of urgent intervention orders that need to be issued and decide now is the time to strike, while it is quiet.

But on their way, a slight detour has to be made when a radio call reports four children believed to be under the age of nine are on the roof of a vacant home.

A property search by torchlight finds no sign of a disturbance. But the home did have smashed windows and a wheelie bin was precariously placed beside the house, giving easy access to the roof.

Maybe the police were just too late.

Another radio call, and we are now on the lookout for five or six motorcyclists reportedly hooning around. Once again, we can find no sign of them.

The job is closed and it’s time for the next one: a person passing by a home has reported hearing a man and woman arguing inside.

Family violence is one of the main problems facing the area, Sen-Constable McCarthy says.

A knock on the couple’s door and they are embarrassed.

It was meant to be a romantic night in for them without their children, who were with a babysitter, but they had been fighting over financial troubles.

They had never had police involvement.

The jobs continued to flow in for the rest of the night — but on all accounts, it was a quiet night.

THE starting blocks at the 1956 pool became the beginning of a stellar swimming career that would establish Dawn Fraser as one of our greatest Olympians.

Fraser, who won two gold medals and a silver in freestyle events at the Melbourne Games, remembers it like it was yesterday — and the nights back at the village even more so.

“Everyone got along very well with one another,” she said. “It was very close-knit.”

She recalled the three-bedroom house she shared with eight other competitors being “very comfortable” but admitted four of them had to sleep in the lounge and dining areas — something some bigger families in the village are forced to do even now.

She also had fond memories of soldiers called up to man the fence that separated the male and female competitors’ quarters.

Fraser, now 78 and living in her home state of NSW, said, at the time, she thought it was a wonderful idea the athletes’ lodgings would provide a roof over the heads of those less fortunate after the Games.

“All the villages I’ve stayed in have been allocated as public housing after the Olympics and that’s the way they were built. I thought that was a good thing,” she said.

But to hear what Melbourne’s 1956 Olympic village has now become saddens her.

“It is a shame it has turned out the way it has,” she said. “I think if anything like that happens to an Olympic village and you’ve spent so much time there, it’s quite sad. You’d think the government would do more for it.”

Her last remark is one that echoes throughout the village.

Ms Fraser said she and other former Olympians were planning a reunion in Melbourne for the 60th anniversary of the Games, in November next year.

“Whether we’ll go out and take a look at the old village as part of that, I don’t know,” she said.

One man trying to make a difference is Tony “Scrappy” Bordonaro.

The 63-year-old has lived in the area for 20 years and volunteers at Alice House, a Ramu Parade home dedicated to helping residents in need with food relief and educational programs.

Exodus House, Olympic Adult Education and the Salt Foundation use the home, which was loaned to the community for five years by the family of its late owner Alice Bohm.

“A lot of people around here need a bit of help,” Mr Bordonaro said. “I sort of consider them all my family in a way.”

To the locals, Mr Bordonaro is an unsung hero. Every Tuesday, without fail, he picks up food relief packages from Foodbank headquarters in Yarraville and delivers them to the residents.

He is also a supervisor for the work for the dole program that runs in the community garden at Alice House.

Mr Bordonaro said the biggest problems facing people in the village were drugs, alcohol, poverty and domestic violence.

“More definitely needs to be done to clean it up,” he said.

A free community dinner at the halfway house attracts about 50 residents every Friday night.

“There’s some good people who are just down on their luck,” says Roger Donnelley, founder of the Salt Foundation, who runs the dinner with wife Catherine.

“We put food into the mouths of 700 people in the area every month,” he says.

DEANNE Bunn, 31, is considered a newbie but says the multicultural community has been welcoming.

“It’s nice here, and we’re all together as a family, so that is the main thing,” says the young mother of five girls.

She admits she was hesitant to move to the notorious area when first offered a home by the Government, but says she has felt safe in the 12 months she has lived there.

“You do hear things so I was worried. But we’ve had no problems at all.”

The home she shares with partner Matthew Wickham and their daughters is one of hundreds pencilled in by the Government to be demolished and rebuilt under a 10-year urban renewal project.

Home is what you make of it, according to Beryl and Alfred Brooks. And the Olympic village has been their home for almost 60 years. They were among the first Melburnians to move in after the Games closing ceremony.

“It was a bit of a rough go in the beginning,” Mrs Brooks, 84, said. “They started off that they didn’t want fences, but that didn’t work out. We didn’t have a shed, so if you went out, anything that wasn’t chained down, went.

“We stayed here though. We were quite happy here.”

The pair, together almost 70 years, raised their four children in their Liberty Parade home.

They were was allocated the quaint little house after finding themselves in emergency housing at Camp Pell in Parkville after Alf’s mother died.

“We were very lucky to have got this house — there was a terrible shortage of houses,” Mrs Brooks said.

They later bought the property from the government for just over $4000 — a far cry from the median real estate price of $500,000 in Heidelberg West these days.

“I wouldn’t want to move anywhere else,” Mrs Brooks said emphatically.

And her husband agrees. “We won’t leave here until they carry us out,” he said.

The Brooks consider themselves from “the good part” of the village.

“It is very quiet up our end,” Beryl said. “I have a friend who lives right up the other end. Oh, they have house break-ins and all sorts of things going on down there.”

Their home was occupied by Japanese athletes during the Games.

Pointing to a wall in her dining room now covered in wallpaper and family portraits, Mrs Brooks said underneath lay spike marks from running shoes “all up the walls”.

“I guess they were just practising,” she said.

“Some of the houses were damaged something shocking at the time.”

From grand beginnings to often crumbling condition now, the walls in the Olympic village hold plenty of stories. Many will be grateful they cannot talk.