A look back at the incredible history of Melbourne’s Chinatown

IF only the walls could talk in Melbourne’s Chinatown. It’s the oldest Chinese streetscape in the western world, surviving 160 years despite Australia’s harsh immigration laws that lasted almost 75 years.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

RESILIENT is the word that describes Melbourne’s iconic Chinatown.

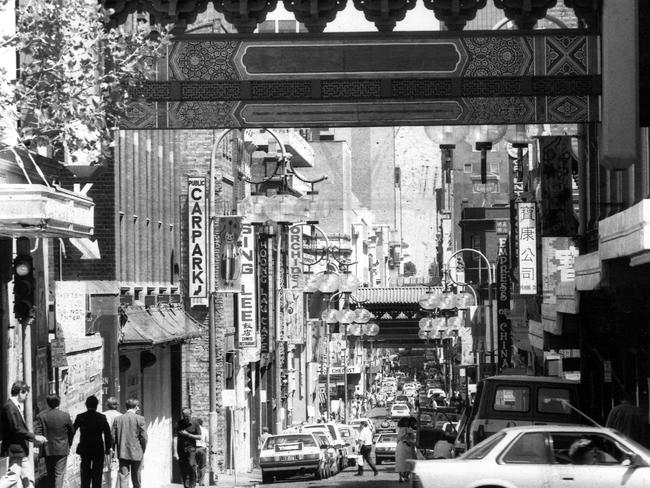

It’s the longest continuous Chinese streetscape in the western world and when you walk through the grand archways on Little Bourke Street it’s like being transported across the seas.

For Melbourne’s diverse Chinese community, Little Bourke Street has been a bustling centre of trade and community for 160 years.

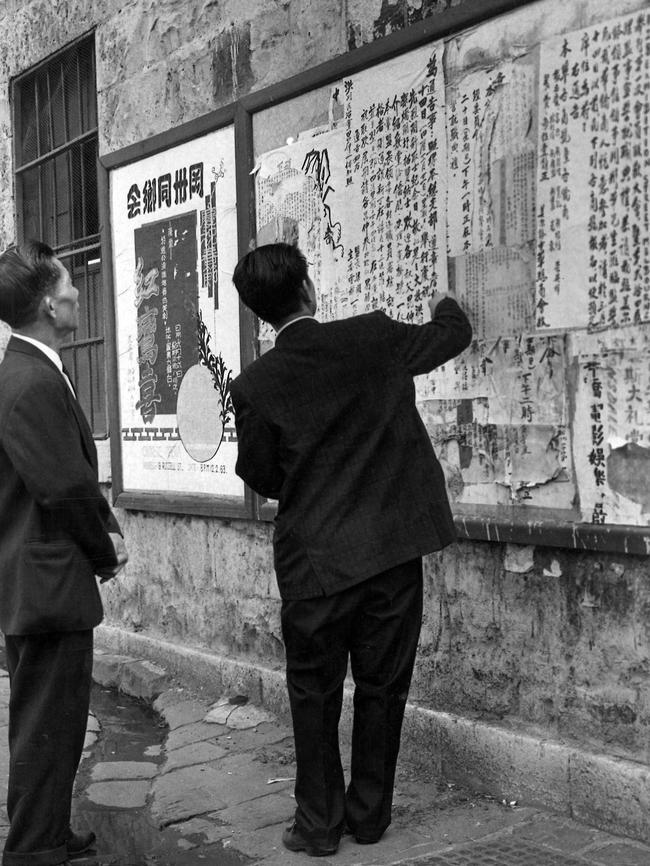

Despite intense racism and a White Australia policy that spread fear and xenophobia, the Chinese community managed to flourish, continually reinventing and adapting in the face of adversity.

Take a look back at the development of Melbourne’s Chinatown, from a crude settlement to a permanent celebration of Chinese ingenuity.

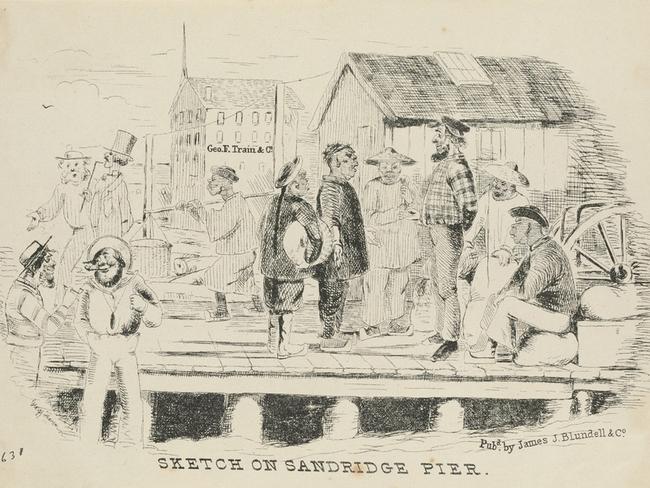

Ships set sail from Hong Kong and China when gold was discovered in Victoria in 1851. Like many people from across the world, the Chinese settlers left everything behind to take a punt on finding gold.

But Melbourne soon became suspicious of the Chinese, and in 1856 the colonial government of Victoria imposed a £10 tax on Chinese people disembarking from the Port of Melbourne — a tax which didn’t apply to any other nationality.

The tax was more than people could afford and most were taken to a port in Robe, South Australia, and had to walk more than 500 kilometres back to the Victorian goldfields through tough terrain.

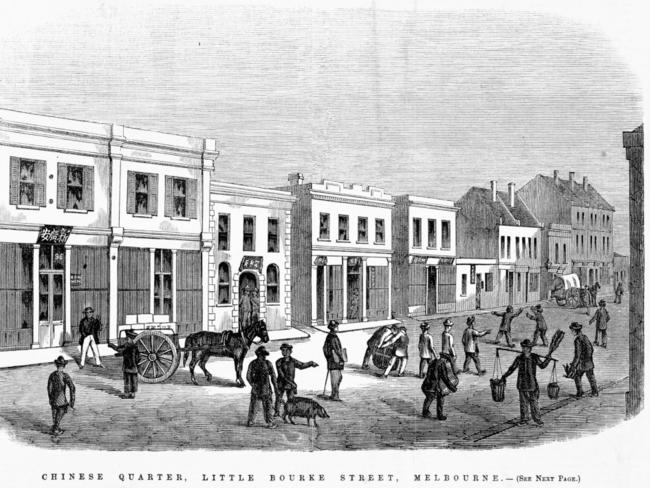

Some of the new Chinese arrivals set up a community in Little Bourke Street that provided all the needs for the diggers, including accommodation, food and medicine — which would pave the way for the modern Chinatown we know today.

By the 1860s many Chinese district associations began to purchase land to build clubrooms which served as meeting places for the community — and the first lodging houses were set up in Celestial Avenue, explains Mark Wang, deputy chairman of Melbourne’s Chinese Museum.

“Chinese people needed a place close to the port to refresh themselves as they had been on a two month journey from China,” he says.

“The first buildings were wattle and daub huts, there were no brick structures then”.

Wang’s great grandfather was one among the first wave of Chinese people to arrive in 1857 and his family has had a connection to Chinatown on one way or another since that time — including having numerous shops and being instrumental in the development of the precinct.

Strolling along Little Bourke Street there are buildings that have been owned by the same families since the gold rush — and the restaurant on the corner of Celestial Avenue is still on the site of one of the first Chinese eateries which opened in the 1860s, complete with the original bluestone wall.

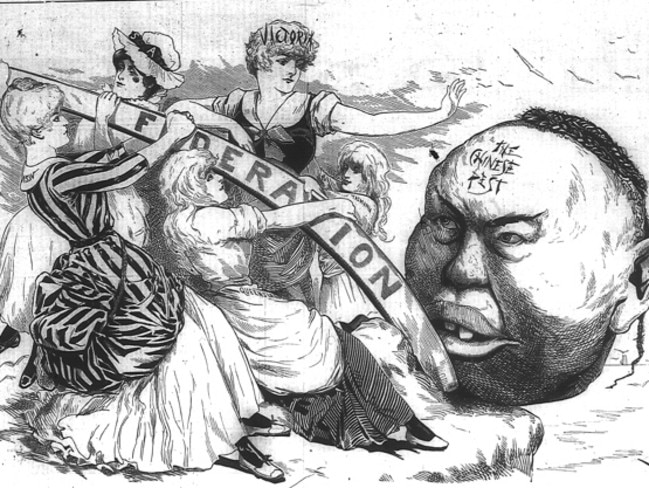

The street was bustling until a nationwide immigration scare campaign — which included many racist cartoons in newspapers — that paved the way for Australia’s White Australia policy.

“The first act of Parliament for the federation of Australia was the Immigration Act of 1901 which lasted for 75 years,” Wang says.

“Once enacted, no more Chinese people could come here and many people just went back. So by the late 1940s, the number of people in the census that were born in China went down to 12,000 in the whole of Australia.”

But even through these difficult decades, Chinatown survived though the sheer closeness of the community — who were self sufficient and resourceful.

With the eradication of discriminatory immigration regulations in 1973, there was an influx of immigration from Chinese communities from around the world and Chinatown bustled with over 100 restaurants by the 1980s.

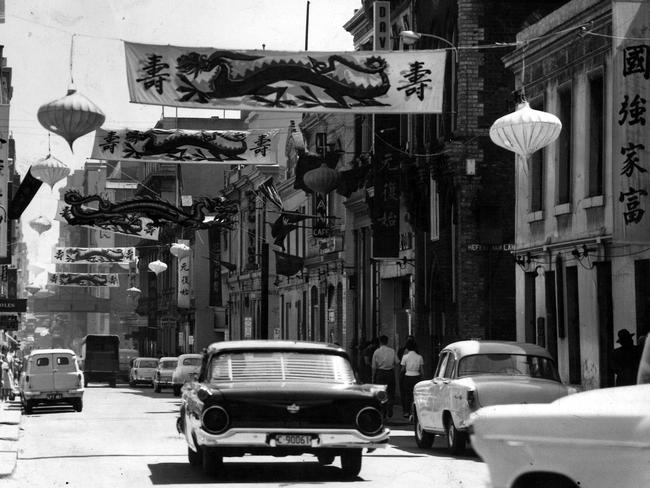

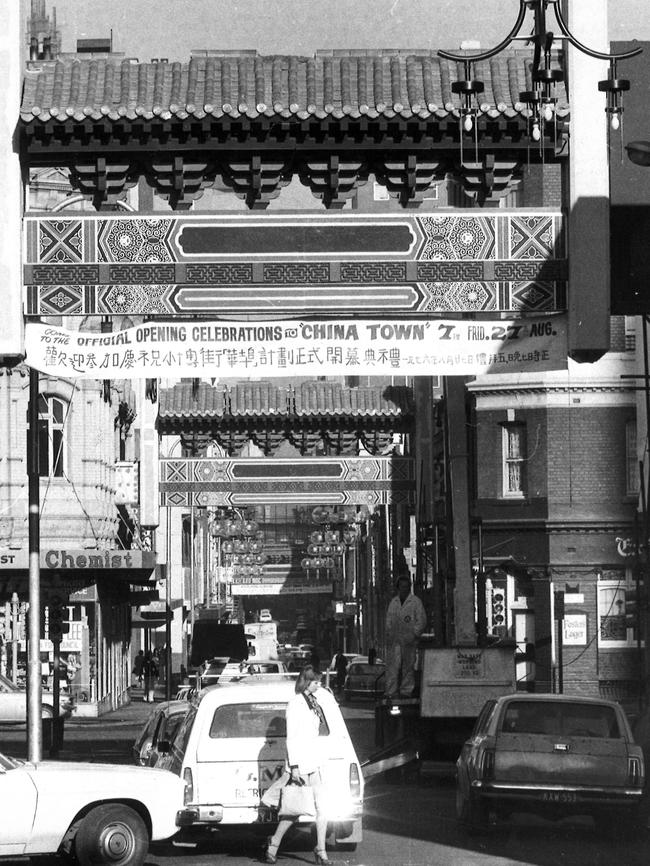

In the 1960s, in a spirit of nostalgia and inspired by the tourist dollars that were being made in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Chinatown entrepreneur and city councillor David Wang (Mark Wang’s father) persuaded the Melbourne City Council to embark on a radical redevelopment of the Little Bourke Street area, including the ornate, colourful arches over the street.

Many were against the development as they resented being treated as curiosities rather than the Australian citizens they were.

“There was a backlash against the arches because some Chinese people thought they were making Chinatown into Disneyland,” Wang says.

“But my father pushed it through and that was really the first recognition of Chinatown.”

By 1985 it was decided to embrace the term Chinatown and the area was recognised for its importance as a tourism hotspot and culturally significant site.

The advent of Don Dunstan as chairman of the Victorian Tourism Commission in 1983-4, brought new enthusiasm and Victorian government funding to Chinatown.

A second phase of redevelopment commenced in 1984 that involved the reconstruction of the archways, the installation of the theme lighting, paving, and the establishment of the Chinese Museum in Cohen Place to mark the Chinese community’s historical heartland.

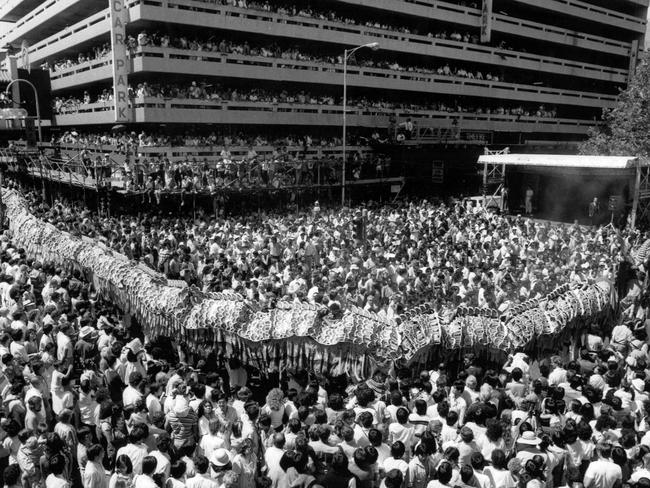

Festivals began celebrating Chinese history in the city by the mid-80s — including the incredible Chinese New Year celebrations that douse the city in vibrant colour as the museum’s impressive dragon is paraded through the streets.

The museum’s collection is almost entirely made up of donated items that represent Chinese life in Victoria — a truly unique and eclectic look back at the lives of some of Melbourne’s earliest inhabitants.

The museum also has Chinese gravestones from the Gold Rush era that were found in a driveway in the suburb of Brighton.

“A guy said I’ve dug up my paving in my driveway and I’ve turned it upside down and there’s Chinese writing on it,” Wang said.

“They were in fact gravestones, which have the person’s name and the date and the village they came from, so were quite traceable.”

The museum is well worth a visit before embarking on Chinatown — with explanations of the history all the buildings along the street. They are currently showing an exhibition on the Han Dynasty that is part of a private collection not normally in the public domain.

The museum also took the lead in an archaeological dig in 1999 in Cohen place (opposite the museum) that uncovered around 10,000 items including clay pipes and coins — a snapshot of life in the Chinese precinct in the 1800s and beyond.

Despite racism, economic downturns and the decentralisation of Melbourne’s Chinese community, Chinatown has remained a bustling precinct that is continually changing.

These days the area is crammed full of students queuing for dumplings, mostly unaware of the deeply rooted history of the buildings that surround them.