Tylenol killer still eludes Chicago police 35 years on

Thirty five years ago a major hunt was underway for a killer who poisoned people using a popular pain killer.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

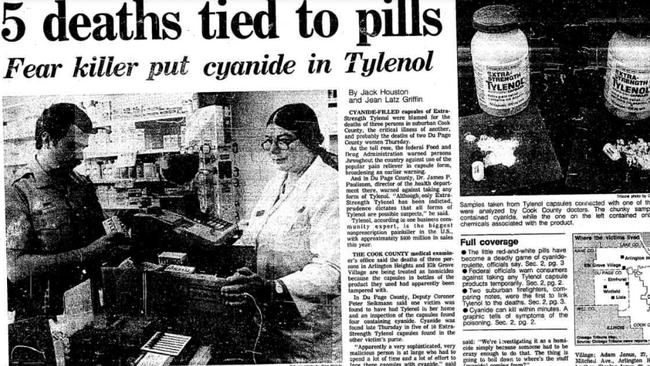

IN the US in October 1982 people looking for pain relief suddenly died after taking what they thought was a harmless painkiller. Investigators soon realised that the victims, all from around Chicago, had taken Tylenol which had been laced with poison.

The drug was withdrawn from shelves in Illinois and after the death toll reached seven, 35 years ago today, on October 5, the manufacturers, Johnson & Johnson, issued a nationwide product recall, preventing any further deaths.

The crime would become known as the Tylenol murders. It would also change the way drugs were packaged. But the murderer was never caught and the crime continues to baffle police.

Back in the early ’80s medicines were packaged in bottles with cotton wool under the screw-top lid. It made it easy for the killer to remove pills from the shelf, add cyanide and replace the bottles in the shop. There was no obvious evidence of tampering and anybody buying the pills was unaware anything was wrong.

One unsuspecting buyer was a parent of 12-year-old Mary Kellerman, of Elk Grove, in Chicago. On September 29, 1982, Mary woke up with a cold. Her parents kept her home from school and gave her an extra-strength painkiller. Her father later said he heard her go to the bathroom and fall.

He called out to Mary to see if she was okay, but got no response. Pushing open the door he found her unconscious. An ambulance was called, paramedics tried to revive her but she was later pronounced dead.

Later that same day postal worker Adam Janus went home ill from work, picking up some Tylenol on his way. At home he took one and went to lie down, but later staggered from his room and collapsed. Paramedics couldn’t revive him. Janus’s family, dealing with grief, gathered at his home where his brother Stanley took a pill from the same Tylenol bottle for his back pain and wife Theresa took one for a headache. Stanley died soon after and Theresa died in hospital two days later.

Medical staff who had attended the Janus family began to ask questions.

The rapid death of three family members was suspicious. Investigators combed the house and found a bottle of Tylenol with six capsules missing.

Meanwhile, in nearby Winfield, Mary Reiner became another victim. After taking some of the painkillers, she collapsed, could not be revived and was later pronounced dead.

Mary McFarland, working at a shop in a Chicago suburb, told colleagues she felt unwell and took some Tylenol. She soon dropped to the floor and was taken to hospital where she also was later pronounced her dead.

Investigators examined Tylenol bottles taken from the scene of two of the deaths and found they smelled strongly of almonds, an indication of cyanide. Tests later confirmed their suspicions.

Johnson & Johnson were informed and acted swiftly to pull bottles of Tylenol from the same batch from Chicago shops and advertise that the product had been tampered with. Police called a press conference to warn of the potentially deadly pills, but it was too late for Paula Prince, whose body was found on October 1. Then all Tylenol was pulled from Chicago stores.

Police went through city streets with loudspeakers warning about the tainted drug. On October 4, Chicago’s City Council passed an ordinance requiring drug companies to use tamper-resistant packaging. The next day Tylenol was removed from all stores across the US.

Over the ensuing days police battled hundreds of copycat cases and struggled to find leads. The murderer had left no clues and made no ransom or other demands.

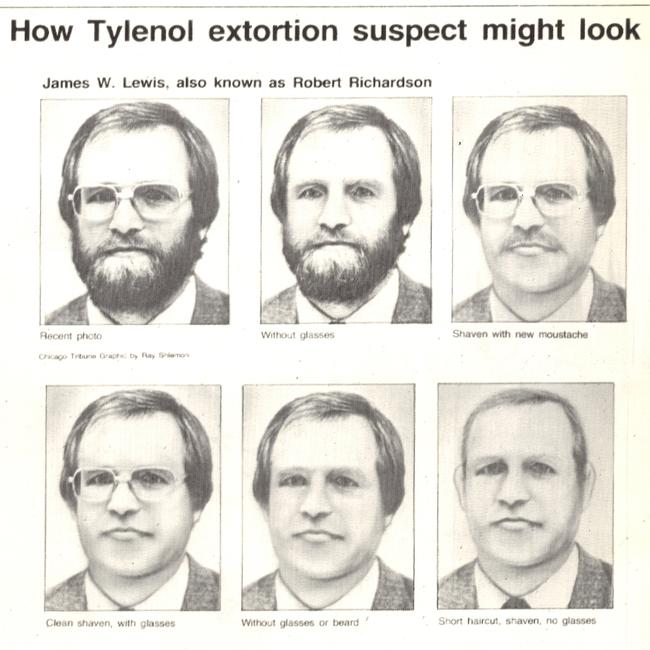

In mid October a letter asking for a million dollars to “stop the killings” was sent to Johnson & Johnson by tax consultant James Lewis.

Lewis had been a suspect in a 1978 murder but had been let off because police found the body in his attic during an illegal search. However, police were unable to link Lewis to the Tylenol murders. But he spent 12 years in prison for his extortion attempt.

Early in 1983 Chicago police called in renowned FBI profiler John Douglas. He believed the killer could be drawn out by being enticed to visit the home of a victim. Police released details of the address of where Mary Kellerman had lived, but the killer never showed.

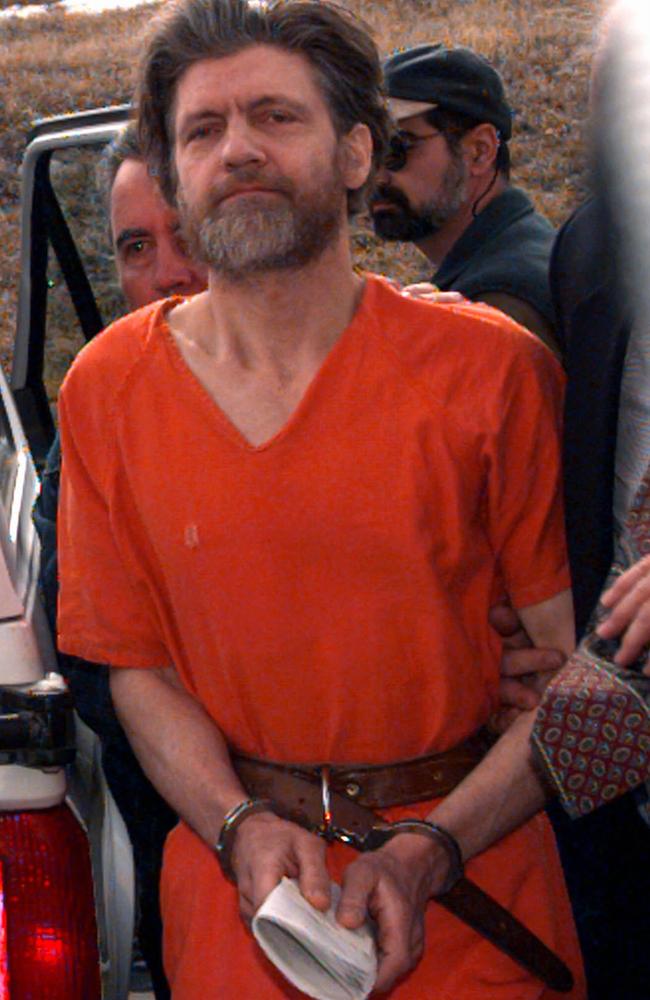

In 2011 police also investigated Ted Kaczynski, better known as the Unabomber, but he was also cleared.

While the killer still remains at large, the crime had a major impact. In 1983 the US government passed a law making it a federal offence to tamper with products. And in 1989 the Food and Drug and Administration introduced new rules for tamper-resistant packaging.

Originally published as Tylenol killer still eludes Chicago police 35 years on