This is the story of the someone who seemed to have everything he’d wanted as a young man, though he was missing a key element, happiness.

No.1 draft pick in the game he hoped to make his life, premiership hero in a drought-breaking win, a girlfriend in his life he would later ask to marry him, handsomely paid, physically healthy. He had it all, but felt he had nothing.

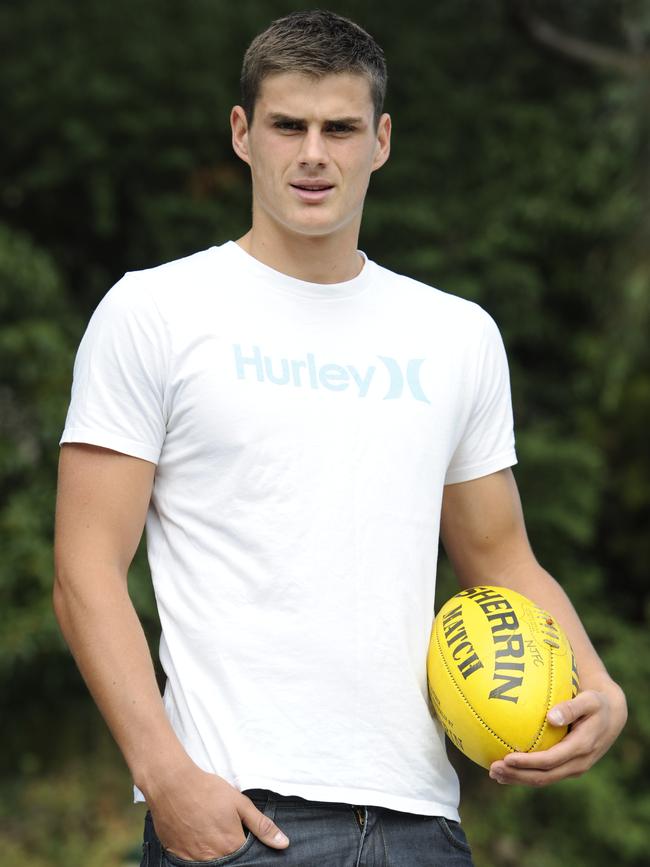

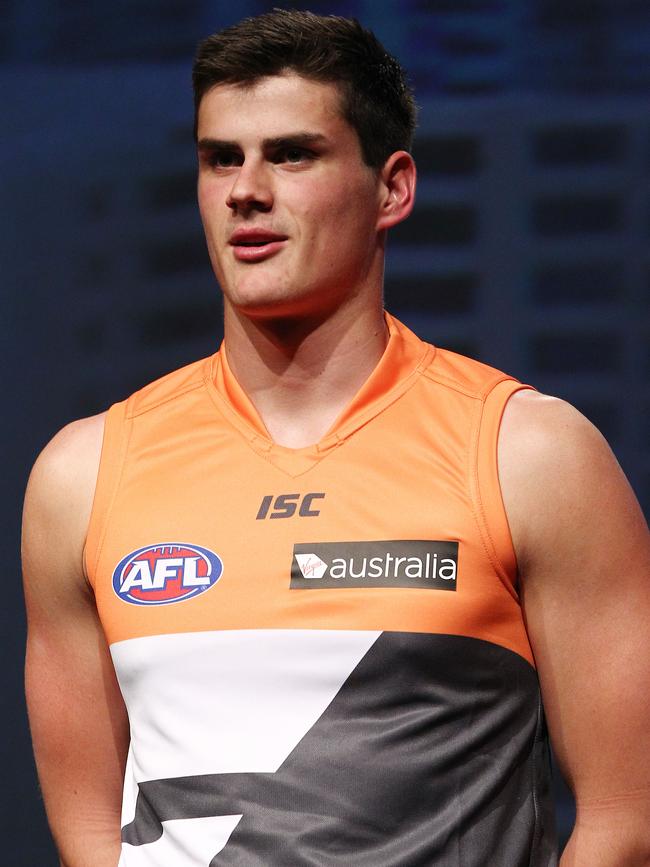

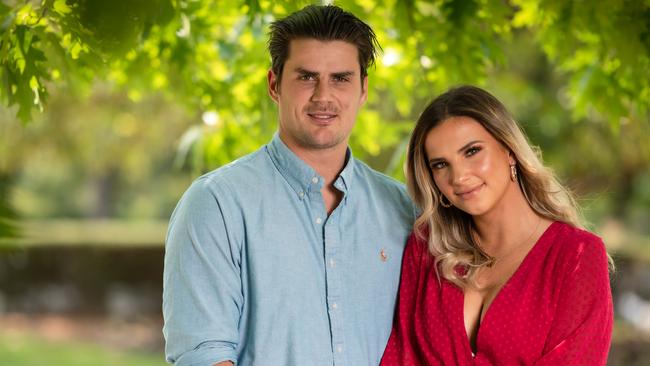

Tom Boyd played 61 AFL games for Greater Western Sydney and Western Bulldogs. After battling mental health issues, Tom retired two-and-a-half years before his lucrative contract was up.

He forfeited the spotlight, pending fortunes, and in doing so, found everything he was hoping to.

HM: What’s your earliest footy memory, Tom?

TB: Arguing with Dad when he was my coach in under-8s.

You knew more than him?

I was just a stubborn kid. I always loved footy, and one of the sad things about my story is how my brain got in the way of the joy of it over time, because I knew I was really good and could turn it into a career.

It stopped being a game full of joy?

Yes, and I wish it hadn’t. I remember when I was four or five, we’d just go down to Norwood where my old man played and the ground was just an oval of horrendous mud. It would be bucketing down, in the middle of July, but I would always be out there kicking the footy. It was the highlight of my week. It was what I looked forward to most.

One of the great things about the game is that at half time in the mud of a suburban game, you can be kicking the footy with your dad, dreaming of the future, and being the happiest you can be.

How old were you when you thought, this is what I want to do as a life?

Early — I swear it was when I was seven. That’s when I thought, “I’m going to finish school and be an AFL player”. I think it just appealed to me at the time, and then it became more realistic as I grew up.

You were a very good youngster, became a prodigy, and as a result lived with a bright light on you for a couple of years leading into the draft when you were selected at one. Had you lost the love of the game pre-draft? Had it become a business and professional in your mind, well before it did?

To a degree. To put it into context, at 15 I was doing nine sessions of sport a week. I was playing basketball in the same age group as Dante Exum and Ben Simmons was the year below me. I didn’t make the state team, but I was state squad level, just outside that first 15.

I did that as a 15-year-old, and then the next year was the under 16s carnival. I knew a decision was coming — I loved both, but footy was always going to be the option. So I started to get serious at 15, and from there it became all-consuming as I was desperate to make it.

The under-16s carnival was a fork in the road moment for you?

It was. I went to the carnival as captain of Vic Metro U16s, and I played terribly. That was the first time where I thought to myself, “I’m going to have to make a serious commitment or I might waste what I’ve been given”. I knew I had the talent. The next two years I was head down. I worked hard and ended up being team of the year in bottom age of the U18s, and I won the goal kicking in my bottom age year when we finished last.

And the external chatter started, and you could hear it?

It did, yeah. “Where’s he going to get drafted to, will he go at (pick) one?” You try and avoid letting it consume you, but it is very hard. You are a young kid who wants to be drafted, all my mates and I talked about was what might happen. When you finish TAC Cup, and the Grand Final and AFL is done, in December they start talking about the next draftees and I was always in the conversation as a potential No.1 pick.

That was going into your final year of school — which you reflect on now as an escape from the football?

It was, yes, but I loved school. I knew once I left school I wasn’t going to be able to see all my mates as I was told some time before the draft that I was going to the Giants. I was savouring my schooling career. I loved school because it was academically challenging, which I really thrived on.

Back then I had perfect balance, was able to go to the beach a bit, surf, have fun with family and friends and not feel any sense of weight or burden as I hadn’t been drafted at No.1 yet. Everything was still free and easy and level. You lose a lot of that when you go into the AFL system. Everyone does. Trying to hold onto some of it is the important part, I’m a true believer that balance is an integral part of life.

And you started to suffer with anxiety?

Yes. I think my problems first started when I got to the Giants. It’s easy to conflate as a young person what things are. Being away from home, I thought it was homesickness — I didn’t think it was something more sinister. It’s very hard to differentiate, and the messaging around homesickness was a really big thing at the club as there were so many young players from elsewhere there together. It’s still commentated about, generally, in the league.

The ‘go home’ factor.

Yes, it can be very real as people don’t want to live away from their family and friends. And the effects are amplified when you are young, insecure and in a high-pressure environment.

So I thought my stress was related to being away from home. I thought everyone’s been through it … I just need to get on with it and get through it. Inevitably, I wasn’t able to, because it was something more sinister which I didn’t consider until I was in a pretty dark spot.

Was it naivety, a lack of introspection or awareness that you didn’t know that it was more?

Probably all three. When I finished school seven years ago, there wasn’t anything taught to us about mental health. Sadly, when I was at school, the kids who had mental health issues were thought of as the ‘weird’ kids. To a degree, people with more severe mental health issues get addressed because they are more obvious and stand out, but so many were having issues that I didn’t know about, and often they weren’t aware themselves because we never spoke about it. I think we’ve come a tremendously long way in seven years.

You arrived at the Giants post-draft in November, and in January, before playing a game, you get offered an extension. What was your response?

“No way, I can’t sign on now”. That was my immediate thought — straight away. I didn’t think much of the offer at the time, as I was a very pragmatic person, and I knew the Giants would try and extend my existing two-year deal anyway, so I was expecting it. Historically, they give you a one-year extension. Even on draft night some players will sign it. I knew I had value, generally, so I didn’t need to sign. I had time, so even if the first two years went horribly wrong at the Giants, I was still going to have another offer somewhere. I didn’t feel that added pressure of trying to elongate my career early on. It was really good money they offered, but it was never about that.

It was just too early for you to commit to being away from home for longer?

I hadn’t played a game — I didn’t know what it was like to be an AFL player, I’d never seen the inside of an AFL game on game day, so how could I make a logical decision based on something I had no information or feel about? That was how my brain worked, and I don’t regret not signing.

That was in January. You were already thinking ‘I’m not signing for another two because that would be four, I’m unsure of the environment, and I’m homesick and finding it all difficult anyway’. When did do you become aware that there was more than homesickness, and there was anxiety, and when did the insomnia start?

The insomnia wasn’t until much later. Generally, I was having issues with sleep, and one of the most important things to understand about people with mental health is that they often withdraw themselves from people and social events.

Had you done that historically?

No, never, but I started pulling away at GWS in a fashion that I could justify to myself. I remember speaking with Phil Davis when I was up there. He said “You need to spend more time with the boys.” I thought to myself: “Well, I am. I’m spending all day with them. I live with them. When I get my own time, I want to do my own thing.”

Looking back, if I was trying to create a long-term career at the Giants, I needed to go out and create relationships with my teammates outside of the game and away from the club. I didn’t do that at all. That wasn’t helpful, particularly early in my career.

I would go off and surf, and do all these different things, mainly by myself, because I thought I needed a break from the club. Now I know, I try and express to people that, generally, there are often signs of your mental state declining, and you need to be aware of them.

Is it true in the middle of your first year, you contemplated retirement?

It certainly occurred to me and I gave it some thought. I had this feeling that I didn’t really fit into the AFL environment. Very early on I thought “This world just doesn’t seem right to me”. I’m couldn’t put my finger on why I thought it initially, but over time, I’ve worked out why I was battling with it.

I was brought up well-mannered, and Mum was always big on that. In my world it was important to be a good person, be polite, friendly, respectful, and that’s what was important. I found that once I got into the AFL world, it didn’t count for much, and all that counted was my performance on ground for two hours every weekend. There was a massive conflict for me with that, because as much as I could achieve during the week, whether it be interaction with my teammates, or effort at training, professionalism, friendship, it didn’t matter because if I didn’t do the right thing and get the right stat line, or make the right impact on Saturday, I was essentially a failure. I’ve never been able to get my head around that. Rightly or wrongly, I always felt at odds with that.

Your worth, and feeling of value, came down to two hours of performance.

Yes, which I understand is a critical part of the sport — winning — and high performance is critical and needs to be a big part of the game, it’s the way it has to be. But I can’t live my life like that, it doesn’t make any sense to me emotionally, or mentally. So there was always going to be a big philosophical challenge for me, and that would lead to the issues I developed.

Was being in a young team, surrounded by young minds at the GWS, a better or worse environment than other clubs?

I’m not sure, but we were stockpiled with of all of these young, highly-talented draft picks in a supremely competitive environment. I’m sure all clubs are ultra-competitive, but at GWS no one was ever really safe in the team, but no one was too far away either, so there was a broad mood of uncertainty and apprehension, and I didn’t handle that well. I was never sure where I was fitting into the team as I wasn’t playing good enough footy to try and get a consistent spot in the team. I was the No.1 pick — I felt I should have been performing better — it was a frustrating experience for me.

Since you were seven you’d wanting to be an AFL footballer — then, when you had become one, in your first year, you suddenly weren’t sure you did.

Contradictory, right? What do people say — “be careful what you wish for”. For a lot of people they thrive, for others they can’t work it out, and it’s not the right environment. It’s a different environment — part of it makes you grow up really quickly, and part of it stops you growing up at all.

Meaning?

As a player, you never really had to make any life decisions, because your working life from day one at the club has been consistent and predictable. Turn up, train, pay cheque, everything scheduled, settled-routine, keep playing well, get married, have kids. It’s a terrific environment if you are good enough to make it, and can handle the outside noise.

The downside of all that is it can delay you from making some of life’s decisions. However, after a career ends often players go “Right, well, what’s next?” You are so busy playing and trying to keep your spot, you’ve forgotten to plan for life without footy. Even for the players, like me, who did think a lot about it the next phase while I was playing, it was still very difficult.

After I was finished, for the first time ever, I couldn’t see what was happening in my life a month away. It was a bit frightening to be honest — nothing was scheduled and in the diary like it always had been. It seems trivial, but that was daunting, and a massive shift for me.

It’s like Shawshank Redemption, when Brooks gets out after so many years and can’t deal with society. Institutionalised.

I think it’s similar. If we are going to avoid that feeling, it’s going to have to be a joint effort across the board to be constantly educating the players on so much more than just playing football. It’s going to have to be a big buy-in process from the league, the union, the clubs and the players. It’s going to have to be a deliberate approach to help create a safe, sustainable life during and post-footy.

We need to try and create a fulfilling environment even if the players aren’t in the best environment, and once finished, we need to ensure there isn’t a feeling of a loss of purpose. For a lot of players that is really, really challenging.

You seem to be the normal, in reverse. You found purpose, joy, and happiness, post-football?

When I was going through school, every moment along the way went to plan. It went well at primary school, well at high school, well in sports, good grades, played good footy; tick, tick, tick …

Good family, stable environment.

Beautiful partner, now fiance. It all went well, and I never had to make any big calls. All I did was follow the laid-out path — I just kept walking on it and I never had to deviate or go out on a limb or have to say, “What’s next?”. When you do, you find out who you are.

That’s when you find out what you actually care about, because you have to choose. For the first time ever, about a month after I retired, I got up in the morning, went for a run, went to an early meeting, then another business meeting, then had footy training in the evening. Everything I chose to do that day, I had created and chosen myself. All of it was my choice. My schedule. Everything I’d done since I’d woken up was all on my terms. I’d never had that happen that I could remember in my life, and when I realised that, it was the most satisfying moment.

That happens to you at 23 years of age.

Yep. I’d been so scheduled and protected I guess. I felt liberated.

Back to your playing days, there was obviously a very big offer from the Bulldogs, but GWS was also making overtures of big offers. Did you choose the Dogs to address your mental health issues as much as anything else?

When I chose the Dogs, I thought there was a problem, and a solution. I thought going home would resolve it.

Going home would solve the homesickness?

Yep — cause and effect. I thought going home would solve that. I thought being near family and friends would help, and I would then play better football as I wouldn’t be so unhappy. They needed a forward so I’d fill that role and solve that issue for them and I’d be a regular consistent player and not behind (Jeremy) Cameron and (Jon) Patton as I was and should have been at the GWS. The three of us would never work in one team. And, not unimportantly, I’d set myself up for life financially.

No homesickness, play good footy, enjoy the game again …

That’s what I thought and hoped. Everything seemed perfect, I would be the key forward, face of the club, back to Melbourne with family and friends, highly paid, set my life up — tick, tick, tick. Everything would be as it should be. But that’s not how life works.

That was going into the 2015. How long before you realised that what you had hoped would eventuate, wasn’t going to — and the anxiety wasn’t disappearing, but building.

Somewhere in 2016 I started speaking with Lisa Stevens, our club psychologist. However, in the beginning it was very difficult opening up to her. I remember, Bob (Murphy) had a good observation of me, and again, this feeds back to the stuff Phil was saying to me when I was at the Giants. Bob uses the word ‘cold’. There was a coldness to me.

The problem with not showing your vulnerability is that you actually are very, very vulnerable. I would feel under the pump, but I couldn’t show it because I didn’t want to give anyone the feeling that things were too difficult for me. Males don’t do that, do they? But by not being open and honest and addressing my insecurities, it actually creates more issues, because it creates more people who, instead of trying to help you, are actually aiming their anger towards you because they feel like you’re ignoring them, or not giving them the respect they deserve.

In 2016 that’s all I did. “I’m fine.” I wasn’t intentionally trying to be cold, I was trying to protect myself. What people take from it is, “He doesn’t care” or “He’s not a team player, he’s insular, he’s ignorant.” It can be construed in a number of different ways, but it isn’t the reality.

Not being open, and in doing so, almost lying to yourself?

Lying to yourself is the hardest and most dangerous thing, I think. Because at the end of the day, it’s impossible to make yourself believe you’re fine, when you aren’t.

You were too vulnerable to accept your vulnerabilities?

Exactly. And now I know, there’s nothing wrong with it — and it is so healthy to accept your failings, but I didn’t know that then. I understand completely why I did, it still makes sense, because ultimately showing your insecurities is scary. Protecting yourself is a natural instinct, but what it created for me was no real link between what was actually happening, and what was going on inside my head. That fracture between the two became really hard for me to deal with over time.

I dug myself into a hole where I thought “I don’t care about any of that health or relationship stuff, it doesn’t bother me. I’m just going to focus on footy and try and be the best player I can be and everything will be OK”. It worked for a while, but it was never going to work in the long run.

What was your diagnosis when you got help? Was it anxiety or depression or something else?

I’m not massive on labelling it. I think there are some conditions, obviously, but in regard to me, the best way to describe mental health is that it’s a continuum — everyone sits on it somewhere. You can be the happiest guy in the world, or the least happy. Natural movement, up and down. A good thing happens, you feel good; a bad thing that happens, you feel bad. The danger with poor mental health is that you keep regressing, until the point where great things happen, and you don’t get that spike. You don’t feel that movement of emotion. Call it depression, but anxiety is more real to me. That feeling of being completely overwhelmed.

Pre-football?

No, just when I was in the AFL world. The actual depression side of things, for me, was that bit where there was a clear relationship with sleep. The fact that I couldn’t find the energy to feel joy, and also the fact that consistently there was that disconnect with positive things happening, and me never feeling positive. Everything was a ‘nothingness’. That’s what I would say depression was, for me. Anxiety and depression often go together, sometimes not. They both had similarly severe impacts on my life, and my happiness.

I’m asking this naively but is depression genetic, chemical, circumstantial, is it a combination? If you were a lawyer or carpenter or builder, do you think you would have suffered the same anxiety and ended up with the same levels of depression, or was it the environment that stimulated it for you?

I honestly don’t know about the genetic side of things. I lived a high-pressure life, and I was a historically high achiever in a high-performing industry where there wasn’t a lot of wriggle room to be yourself. A lot of my mental health issues, or conceptual issues within my own head, were due to the fact that I didn’t understand myself. The disconnect between who I was, and who I was portraying, that was always the hardest and most complicated piece of the puzzle for me. It feels very disingenuous, and it’s exhausting trying to be a different person.

When your mental health battle was at its most crippling, what were the effects on you, physically or mentally?

There’s no ability to find joy in anything. To deal with it chronologically, anxiety was something that was very prevalent in my AFL career particularly because I put so much pressure on myself come game day. Over time, the best way to describe anxiety for me, is that it’s like a balloon. You’ve got a balloon with a certain amount of air, and that air represents the capacity that you have to deal with stress. What tends to happen is, when you come up to a moment that makes you feel anxious, you feel like you can’t take any more air in, and you’re just going to burst. Then what you do is you say, “I’m not going to do it. I’m going to avoid confronting the issue at all”.

And then what actually happens is you let a little bit of the air out, and then over time the air shrinks, and shrinks. If I get nervous speaking in front of a thousand people, if I avoid it, then in time I become nervous in front of 500, then 200, then talking to one person is crippling. That’s the general rule around avoidance, and anxiety. My issue is it went from being anxious around games, and then it was main training sessions, and then it was every training session.

Anxious just to go to them?

Constantly. Even to attend the club at times was a significant challenge for me. About everything to do with my football life in the end. I think it was stimulated from just wanting to be perfect all the time.

That’s impossible though.

It is. Chasing perfection isn’t real. I couldn’t stuff up a kick. What happens when you think about not wanting to stuff up a kick? You stuff it up. It’s this self-perpetuating cycle of anxiety.

A life of constant anxiety …

Constant. Over time it transitioned from just being anxious before the event, to the night before, and it would become really difficult to sleep. In 2017 before I had the worst bout of insomnia, we’d train on a Thursday and Wednesday night I’d really struggle to sleep, really struggle to sleep after training, or sleep Friday night, and then I had to try and play Saturday. By the time I got to a game I was so tired, and mentally fatigued, that I would have to use every ounce of energy I had to get through the game. I’d really struggle to concentrate.

Do anxiety and depression fuel each other?

It did for me. My first bouts of depression came after the anxiety had lead me to insomnia around games. Suddenly, it’s Saturday night, you’d played at 7.50pm, it’s 3am, and you haven’t slept yet. It’s quite common in AFL players. Suddenly, I hadn’t slept for three days. I’d just played one of the most gruelling sports in the world for 120 minutes, and I had to be up at 9am for recovery. I was just a wreck. It’s two or three days of just crippling tiredness and fatigue. It was just the physiological effect of the mental cycle I was in.

Sleep deprivation is a form of torture.

Exactly, and then I’d get injured. The body can’t handle no sleep. Sleep is the most important form of recovery, we’re told that since we’re 10 years old. That lack of ability to recover just accumulates over time. My body has always been quite resilient, but it couldn’t go through that. Not any longer.

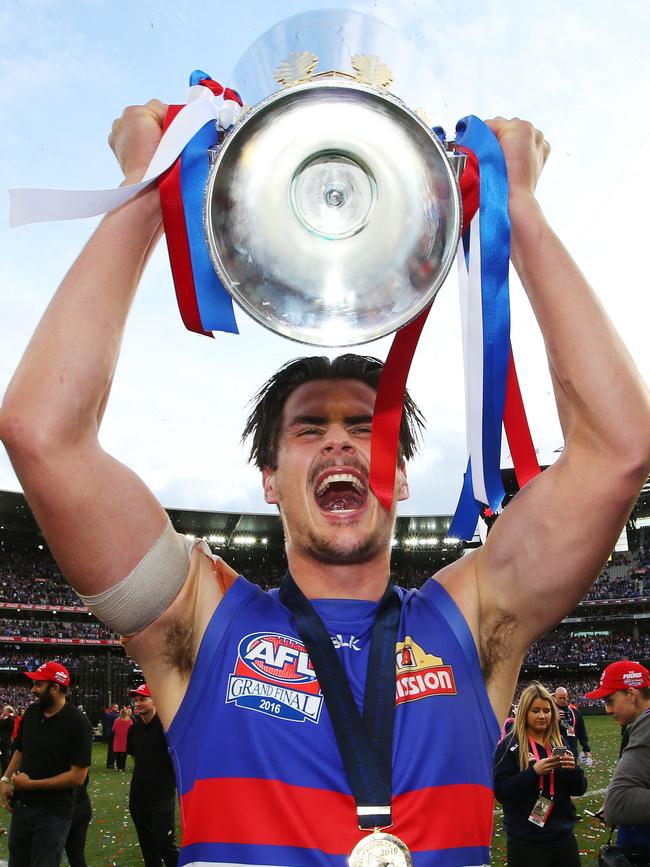

Following the 2016 GF win - did your anxiousness disappear in anyway?

No, not really, it was an amazing time surrounding the grand final where in that month a series of seemingly impossible events were overcome that culminated in pandemonium. I have very fond memories of that time, but once the true elation of victory subsided, I do remember feeling very hollow. Funnily enough, although success aided me for a while, I think in reality it just acted as a distraction from what was really going on for me. So there was definitely joy attached to that period of time, but it was fleeting and the 12 months that followed would prove to be the hardest of my life.

So no sense of lasting relief, or achievement or happiness?

I think the enormity of what we achieved for our club and community was absolutely recognised. Internally we knew the depths of some of the challenges that we faced collectively, so to get there and achieve the ultimate in the game and overcome all that and be victorious on the last day of the year was exceptional. Because of this I think the strength of the relationship between the members of the club became so powerful, so that was a unique experience that is lasting.

You took time off in 2017 — you recognised the problem was so severe you needed to remove yourself. What did you hope to achieve?

Part of what we were trying to work out was what we needed to change. Then we needed to understand me, what I’d been through, and whether I could function normally with football in the equation. We decided I couldn’t. The actual break from football was two-and-a-half weeks, where I had no contact with anyone from the club. We took football out of the equation, and suddenly free up some space to work on my mental health. What we were trying to work out was, when was I actually happy? It was when I was 17, 18, when I had sport, school and family and real balance in my life.

And your balance was off?

I hadn’t had the balance right in a long time. That was part of it. The other thing was trying to work out how to be a little less hard on myself. Invariably with football, we shoot for the stars, and falling short is not something we deal with very well, particularly with me because I felt like I knew what people expected of me, and I wasn’t reaching their expectations. It might not have been realistic, but I still wanted to get there.

Being easy on yourself and meeting others’ expectations — is that possible?

I needed to work out how to do both. I wanted to do well, but I had to be OK with not being perfect. We did a lot of practice-based things that I wanted to put back in my life, like surfing, spending more time with family and friends, sorting out my sleep. We had a number of things that I needed to deal with in that time off to try and become level again.

When you would come out of a dark period, and you were feeling strong, did you think you would be able to beat it and it was in the past?

No. I’ll never forget the power the brain has over the body. One of the reasons that I’m able to talk about this so liberally is because it was so tangible to me. I couldn’t participate in life as I knew it for months and months. Then it becomes much easier for me to calibrate because it’s an injury of sorts; an illness. Something that has a massive effect on your wellbeing, your lifestyle, your friends, family, all your social interactions are implicated in the whole experience.

Are you better at managing things now?

I’m much more resistant to adversity. The way I look at resilience now is, when you’re going through a difficult time, what are the tools you have to help you pick yourself up, and deal with it? They can be mental tools, they can be a desire to not allow yourself to spiral down. From that regard, I picked up a lot of the skills in that time to say, “If things aren’t right, I know I can progressively and proactively change things quickly, and pivot much quicker than I used to, so that I don’t end up regressing a long way”.

How do you keep yourself mentally as healthy as you can be now? What have you learnt, and what are your daily rituals?

I’m a big ‘feel’ guy. Whatever feels right at the time. There are important interactions with people that I need to continue to have. I still see Lisa weekly, and to be honest it used to be an hour of “Tom”, but now it’s 15 minutes about what’s happening in my life, and 45 minutes about where I can best help people. What direction do I need to go. What mediums and platforms and situational stuff can I do, to most effectively, most morally, help people.

I would love to publish my story in book form, or a podcast and certainly in oral form through my public speaking which I love. I’m big on the fact that, yes, I can be an advocate for positive mental health, and I think I can make a big difference with my story, but ethically and morally from my own point of view, I need to do the due diligence behind the scenes to make sure that I’m not pushing messages that are either wrong, or dangerous.

Part of that evolving conversation with Lisa is always important. I make positive interactions on social media around messaging, around this space, and I feel good about myself because I know I’m making a difference. I know that I’m acting in a way that enables people to positively interacting with me.

I think that’s the checks and balances we all have to go through in regard to life, because to refer to my football career, what I couldn’t find was a sense of achievement outside the game. Where am I going? What am I doing outside of kicking the pig skin around that is positive? So I’ve found by acting in a way that makes a positive impact on the community I have a better appreciation for life.

Do you find you are isolating yourself anymore?

Not at all, but I still love my alone time. I don’t seek out alone time, but I utilise it when it’s there. It’s a different equation. That’s an important shift that’s happened over the years.

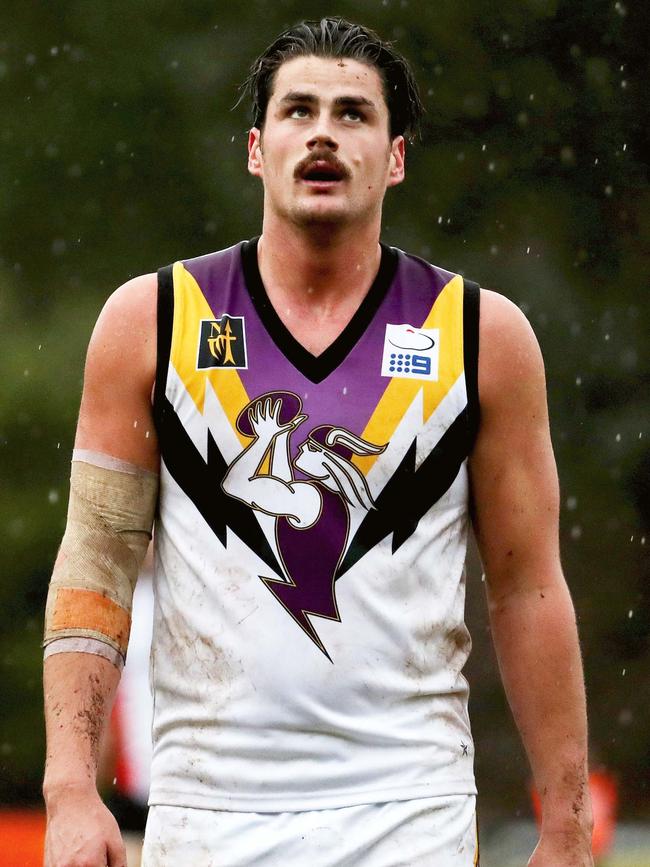

You still love footy, and you’re playing footy. Happy footy.

I’ll work out my love for the game again. The thing that has been misinterpreted with the end of my career is that I hate the game. Not true. That I hate the footy club, or the idea of being around a footy club. Also, not true. I love both those things. The many layers that come with the AFL was what got me, and the different elements of the game that you have to participate in at AFL level. That’s fine. Now that I can differentiate the two things, it’s great.

I’m still going to have to learn to love it again, to really just love the playing side of the game. I’ve had so many traumatic emotional relationships with the game in my past. Immediately, when I finished, I knew it was very important that I got involved on a community level with football. Call it my church, or my community hub, that’s really important to me. It’s an interaction with a different group of people, and I can learn a lot from different people within the community. I’ll be playing at St Kevin’s next year and played a little bit at Norwood this year. I’ll always be around football clubs in some way, shape or form.

Were you a happy kid?

I think so. I don’t remember being unhappy.

Are you happy now?

Definitely. It’s amazing what you can achieve in short periods of time when you’re really passionate about what you do. I’ve seen an amazing uplift in my productivity in the mental health space, but also in my life, because I love what I do. I love what I’m doing, I love the impact that I can have, and I don’t have the spectre of footy hanging over my shoulder anymore. It’s just a part of my life, not my whole life.

To those that are battling, what would you advise them?

You don’t have to do it alone and that as hard as it is to reach out when you are feeling vulnerable it’s so important. It took me a long time to address my issues and I was surrounded by great people. I think it’s the one thing we can get better at, and notoriously Australians are proud of the true Aussie spirit. The spirit of mateship is looking at your mate, and if you sense a change, ask him how they are going. It doesn’t have to be much.

The power of that is incredible, because you might start something where he considers that he’s not going well, or she might not be going well, whatever it is. The fact that we don’t tend to look out for each other as well as we can, or as well as we should, is one of the biggest things that I’ve been critical of.

We’re all going through the same things together, we all understand hardship and adversity in some way, shape or form, so with that in mind there is a certain responsibility to look after people when they are going through hard things. Be on the lookout for when those things might appear.

If you were in Year 12, knowing what you know, would you nominate for the draft again?

I’m not big on everything happens for a reason, but I think that circumstantially we become who we are because of the things we’ve experienced. I think that I wouldn’t be having the same impact on people that I’m having now if I didn’t go through the hard yards earlier. I wouldn’t change what I’m doing for anything. I’m very lucky that at 23, 24, I’ve found what I am truly passionate about, and worked out that at the very core of it, it’s people.

I love interacting with people, I love looking after people, helping people, people helping me. That’s what it’s all about, and it took me a long time to work out that’s at the core of what I want to do.

The 24-year-old Tom speaking to the 15-year-old Tom?

I don’t know if the 15-year-old me would have listened. There are certain tools we can give our youth, in this space in particular, that will hold them in better stead. We are extraordinarily critical of young people growing up today, and part of that is the fact that everything is documented. One of the messages I give to young people when I speak to them is, you live in a permanent world. For the first time ever; you can’t get away with anything.

Which is a hard way to grow up. But, it is reality. Societally, we need to be better at understanding that kids make mistakes. Perhaps some of those mistakes are more systematic of the things they’re going through, rather than them being bad kids, or bad people. From that regard, the fact that if I know more about some of these things, and the fact that anxiety, depression, mental health, life’s not that easy for a lot of it. That’s part of the beauty of it, and the struggle is the reason we keep going. If I’d known that when I was 15, that would have been helpful.

When did you get so wise?

Wise through suffering, I think. That is best thing that I’ve ever learnt about myself. Three years ago, I was an idiot. In three years’ time, I’m probably going to think the same thing about me now. The whole point of progression is that it’s fine to make mistakes, it’s fine to understand that the journey is the whole point. The destination is the end. Why are we running towards the destination? You have to enjoy the journey of life while it’s going on. I’ll tell you what, I’ve made plenty of blues and I’ll continue to make them, but you’ve got to try and learn along the way. That’s the whole point.

In your journey — when was the lowest you got?

I’d been having real issues with insomnia for a number of weeks. What they get you to do with insomnia is, firstly, they medicate you. Generally, it’s not enjoyable because some of the sleeping medication is so powerful that in the morning when you wake up you feel so bad, and so hungover from the effects of the medicine, that it’s not necessarily a better option than not sleeping. The other one they do is they get you to sit in the chair next to your bed. They’ll say, “Sit in the chair until you start dosing off. Get into bed, get out of bed. If you can’t sleep, just repeat that”. It’s part of just trying to bore your brain to sleep. I’d missed a couple of games playing for the Dogs because I had a calf, but essentially it all stemmed from not being able to sleep. I was sitting in my house in Albert Park, middle of winter, July blues, with no end of the season in sight. I was supposed to return back through the VFL that weekend after missing the last couple of games.

I couldn’t comprehend why I was feeling so terrible about myself. I looked across my life and I had a beautiful partner, who is now my fiance, Anna. She was the most supportive person going around. I had a new dog, a beautiful Labrador, an amazing family who did everything they possibly could to support me. I was living in a beautiful part of the world, getting paid a million dollars a year playing the dream job. Everyone in my life was telling me how good I had it, and I am absolutely, 100 per cent miserable.

What happened from there?

I’m sitting there, and I’m trying to work out what I’m going to do next, and there’s not a single positive thought going through my head. I’d worked out a couple of things. The first thing was that I couldn’t play on the weekend, it wasn’t going to be possible. My body wasn’t going to handle it. My mind couldn’t handle it either. I couldn’t go on that merry-go-round that I’d been going on. The second thing was that if I didn’t get help, and change some things, or something didn’t give, I didn’t know what was going to happen next.

MORE AFL NEWS:

MAGPIE STAR OPENS UP ON BATTLE WITH ANXIETY

Who did you turn to?

I’d been seeing Lisa previously, and for the first time in my life I actually called her and specifically asked for help. I said, “Lisa, I can’t play on the weekend. I can’t do it.” Of course, her being her, one of the most amazing people in my life, she said, “How can I help?” That hour felt like an eternity, and I’ve never felt so terrible about myself, and unsure about my future. The one thing that I did was I actually made the effort, and made the decision, to get someone to help me get through that time. Not try and do it by myself. I can honestly say that if I didn’t, I don’t know what would have happened next. That was the last time where I felt so helpless that I couldn’t see anything good in any of my life. That was the hardest day of my life.

It’s a tough equation to try and find an answer to. You had a wonderful girlfriend that you’re now going to marry, a great house in a great country, physically healthy, earning well, playing a sport you wanted to as a kid, but couldn’t feel worse about yourself.

That’s the whole point, isn’t it?

It doesn’t discriminate.

No one is immune, and it’s not proportional to your life. Some of the most powerful, brilliant people in the world have had so many issues in this area. We lose people every year across entertainment, business, sport, politics, whatever it is. This stuff doesn’t see career. It’s all grey. I just want people to know that the choice that I made to actually open up and ask someone to help me, well, that’s the reason I am here happy and healthy and able to talk about it now, and they shouldn’t feel embarrassed or ashamed asking for help. It is brave, and it’s the right thing to do.

When you are at your lowest point, how do the conversations play out with Mum, Dad and Anna?

Differently with all. The ability to process information like this is dependent on how open you are. Anna had been through the whole ride with me, right there by my side. One of the biggest challenges with people who are in her position is that you feel very helpless. You’re doing everything you can, but it’s very important that those people who are second-hand suffering get support as well, because they’re feeling like they’re a part of the ‘not enough’ bit, which is not true, at all. They’re part of the ‘why it’s worth it’ bit. Telling her wasn’t difficult, and she was very understanding about me taking a break.

How were your parents?

Telling Mum was reasonably easy. I’d had conversations with her, and she’s an amazingly supportive lady. She’s always been right there beside me the whole way through. Again, that hopelessness fact is magnified because of her gap, and her distance, so she’s thinking “how can I possibly help without being overwhelming?”. That’s really challenging for the people around you.

Dad?

Telling my dad was an interesting experience, and the reason for that is for all his intent and care, and he was doing his upmost to support me, his life generally has been “if something is hard, put your head down and work harder.’’ One of the biggest challenges is when I walk in and speak to people of Dad’s generation, they find mental health hard to comprehend.

Dad, to his absolute credit, did everything possible to try and learn, try and understand, empathise, sympathise, and that was really important for me to see that. That was enough. He’s been one of my best mates in my whole life, so it’s important that he invested and tried to make the best fist of it that he could.

Have you got better at recognising people that need help?

Not necessarily, I think I have gotten better at being able to see things from other people’s perspective, which I was terrible at when I was younger. People can be very good at faking it, and I was very good, until I couldn’t. The responsibility on us as people is to treat people fairly, with respect, and with value. Sometimes, those people can’t find any value within themselves. I went through that at one stage.

If you treat people as though you’re not worth anything, well you may be contributing to some of it. It’s not always a direct correlation between people’s lives, and the way they feel, but ethically, morally, the response has to be to try and look after everyone. At least treat them as your equal.

One of the things that really resonated with me was when you talked about how you’ve always tried to live a life where you’re well mannered, really respectful of others, try and help others, but ‘because I wasn’t performing for two hours a week, I was getting treated like a terrible person’.

I don’t think that’s a melodramatic statement. It’s pretty accurate. You did your research Hame, but as you know, there’s been some pretty heinous stuff written and spoken about me at times.

Not just from people in the outer on social media.

No. Football is a microcosm of community. I don’t have any qualms about what people wrote in the media, because I understand now that it’s their job. At times, they tend to latch onto players, people, in general, which I don’t think is right. I don’t have the issue or the negative emotion towards those people, because they are often representing a greater story that is the mood, or the way that Australia functions.

It’s been a big ride so far. Thinking you wanted to be a footballer, going No.1 in the draft and becoming one, not enjoying it, winning a flag, and now at 24, all done. You’re not a professional footballer, you’re sitting on the floor with me, as happy as you’ve ever been, after going through hell.

My story has never been boring. In many cases, particularly in the AFL world, it’s very unique. For that, I make no apologies. Over time people have tried to put me in a box, because it’s easy to do. “He’s a highly paid footballer, he has nothing to worry about”. I didn’t want to be different, but because I was trying to work out who I was, I seemed to be. Now I can be myself all the time, act accordingly, participate in life accordingly, and it’s so satisfying not trying to squeeze everyone into a profile that doesn’t fit. That’s where I got my identity crisis from, to a degree. Now I have the option to choose.

MORE FROM HAMISH McLACHLAN:

THE UNCOMFORTABLE CONVERSATION THAT SAVED MARK ALLEN’S LIFE

PHIL DAVIS TALKS OF GRAND FINAL DREAMS AND HIS BRUSH WITH DEATH

McDONALD-TIPUNGWUTI HOPES TO INSPIRE OTHERS WITH HIS STORY

When do you marry the girl from next door?

December 2020.

That’s something to look forward to.

Yes, it is. We’ve got a big year coming up. A renovation, a wedding, a couple of other family members who are in the same boat. It’s exciting. I’m going to have a big change in the work I’m doing, walking into a full calendar year. Anna’s going to experience the same thing, so we’ve got an enormous number of things on our plate, but all very good things.

And no skin folds.

Thank God for that — I’d fail.

(Laughs) It’s good to see you happy and smiling.

Thanks, Hame.

If you would like to learn more or hear from Tom, go to millennialtranslator.com.au

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout