The day two immigrants’ worlds collided on Bourke St

Sisto Malaspina and Hassan Khalif Shire Ali began their final days on opposite sides of Melbourne but a world apart. Hours later, the two immigrants would lie dying on Bourke St just metres from each other.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

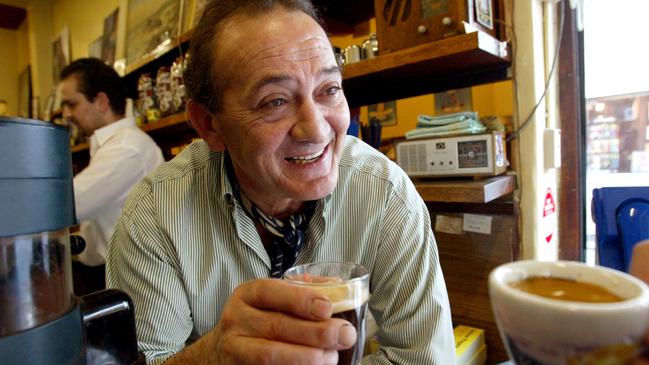

Sisto Malaspina was particularly punctual on the day he would die.

He collected the papers from the newsagent at the top end of Bourke St like clockwork.

At 9.30am he crossed the road and walked through the side door of his popular cafe, Pellegrini’s.

He inspected the till, then poured a long black.

Business development manager Michael Haranis sat next to him.

INSIDE HIDDEN LAIR OF ‘PSYCHO’ TERRORIST

It had been this way for decades.

Creatures of habit, the two friends had found common ground talking for hours about nothing in particular.

They idled on topics like motorbikes and sports cars. But last Friday morning, the conversation revolved only around one thing.

Sisto had become a grandfather.

Son David and his wife had welcomed a little girl into the world a week earlier.

“He hadn’t seen the baby in a couple of days and was desperate to,” Mr Haranis said.

By 10.30am, the immigrant Italian struck up a similar line of conversation with the meat supplier.

He could have chatted in the doorway all day but he knew there was work to do. Fridays were the busiest at the restaurant on account of the chef’s homemade gnocchi.

Scores of customers started to file through for their fix from noon.

It was about the same time, half an hour north in Meadow Heights, Hassan Khalif Shire Ali removed an air compressor from the back of his Holden Rodeo.

It would be a few hours yet before these two migrants would cross paths. As the Somali-born man jostled gas bottles into position on the back seat, Sisto plonked down buttered rolls and held polite conversations.

Shire Ali would have been behind the wheel of his ute by the time the lunchtime crowds at Pellegrini’s started to thin.

As Shire Ali rumbled away from the converted garage where he had been living with his wife and infant son, Sisto was back at the cafe insisting his longtime business partner, Nino Pangrazio, leave in time to pick up his granddaughter.

The pair had taken over Pellegrini’s in 1974, inadvertently becoming pioneers for the city’s cafe culture.

Neither had any plans to retire. Instead they alternated shifts and shared the workload on busier days. Today was one of them.

Mr Pangrazio bid farewell at about 3.30pm. “I’ll see you on Monday,” he said.

He knew Sisto would hang around to ensure the service continued smoothly. He knew too that Sisto had made plans to continue the celebrations for the family milestone.

He wanted to walk down the street to buy chocolate and champagne to share with staff. Some call it fate. Others, plain bad luck.

SUBSCRIBE TO YOU’RE TELLING ME PODCAST ON ITUNES

Whatever the philosophy, it would be about half an hour before the lives of the two men, whose decisions had set them on wildly different pathways, would collide.

Little is known about Shire Ali’s tentative first years in Australia.

He arrived as a five-year-old in the early 1990s as war in Somalia tore the nation apart.

More than half a million people were murdered. Entire families were chased down and massacred as tribal vigilantes fought for control.

Tormented survivors fled to neighbouring African nations and across the Middle East at the height of the civil unrest.

Shire Ali, his parents, three brothers and two sisters would become part of Australia’s humanitarian intake. In a few short years, Melbourne’s Somali community would increase from a few hundred to more than 3000.

His father was intent on creating new opportunities for his loved ones.

He got a job as a factory worker but later became a taxi driver.

Settling into their new life came with considerable adjustment for his kids, who like so many Somali refugees at the time, may never have attended school.

There was a new language to grapple with and an unfamiliar secular culture to digest. Young faces stared back at them in classrooms and on every street corner.

It’s hard to know what impact the transition had on Shire Ali and whether it was a counter point for what was to come.

The first sign of trouble was not until much later.

By 2015, he became a subject of interest for ASIO officers who cancelled his passport after the 27-year-old made plans to head to Syria and join Islamic State.

He had referred to himself online as a wannabe terrorist, voicing his support for IS and how he planned to fight for the ugly cause.

A year earlier, he had communicated with Khaled Sharrouf, the infamous Australian terrorist who had posted a photo of his young son holding a severed head.

In the past 18 months, Shire Ali had been associated with Yacqub Khayr, the Somali man responsible for last year’s siege in Brighton that resulted in the murder of a hotel receptionist.

But in the lead-up to the madness last Friday, while the young man remained on a watch list, joint counter-terrorism teams felt he didn’t pose a threat to national security.

Privately, though, his life was unravelling. He had split with his wife, had become estranged from his family, was taking drugs and had mental health issues.

In the days leading up to the attack neighbours would report seeing Shire Ali storm out of the flat he had only recently moved back in to.

On a scrawled piece of paper, his family would later point to his unstable mind. This man, they said, was not a terrorist. That was never his plan.

Yet before he drove into Melbourne’s CBD, he had spent the night fixing a flat tyre in his driveway and carefully unscrewing his number plates.

Shire Ali was nothing, if not organised.

When Sisto Malaspina took over the eatery he was about the same age as the man who would murder him.

Sisto walked into Pellegrini’s, aged 30, and never looked back. His energy for the industry was founded on Italian shores where his first memories were of helping his grandmother make pasta. She would gently chastise him for not kneading the dough properly. It were those early interactions that planted the seed that would spring to life on his arrival in Victoria. He was eager to pursue his passion for fresh ingredients and warm hospitality.

He found someone who shared his vision in Nino Pangrazio when they met at a reception centre on Inkerman St, St Kilda, called Stanmark. It was a friendship that would stand the test of time and in his business partner of 40 years, Sisto would admit discovering a level of friendship, love and understanding that would sustain them both as well as the coffee they worked tirelessly to perfect.

Nobody is certain of the exact route he took on Friday afternoon. It was just after 4pm when Shire Ali turned into the restricted vehicle zone on Bourke St between Russell and Swanston.

Sisto was walking along the footpath outside the City Duty Free store when he saw the blue ute ablaze and rolling to a stop on the opposite kerb.

It’s understood Shire Ali may have already been out of the vehicle by the time Sisto ran across the road to offer assistance.

The Somalian stabbed him in the neck, just above his collar bone before the restaurateur had time to understand what was going on.

Video footage showed Shire Ali swiping wildly in those final moments before an officer is forced to shoot him in the chest. He falters and falls to the ground between a bench seat and an express post box.

In that moment, the two Australian immigrants whose pathways only briefly intertwined, lay dying just 10 metres apart.

Sisto, the man who would sometimes break into song when he saw a pretty woman, was sprawled on the footpath outside a florist on Russell Place. An off-duty nurse was among the good Samaritans who desperately tried to save him as the horn from the burning car sounded relentlessly and police sirens cut the air.

Sitting in the kitchen of Pellegrini’s a week later, Nino Pangrazio sipped coffee and tried to comprehend the mathematics of a meeting like that.

There was no rhyme or reason to it. Not that he could see anyway.

Always ready for the camera, Sisto would have loved to experience the outpouring of love and unity, the result of his death.

His seat inside now sat empty. A long black sat on the bar next to the papers he might have read. Flowers continued to pile up in his honour on Crossley St.

Well-wishers had been filing into the back kitchen all morning.

“It’s a mystery,” offered one teary-eyed man.

But Mr Pangrazio shook his head.

No it wasn’t.

Tears had welled in his eyes all morning as he attempted to find new ways to explain it.

Sisto was just doing what he always did. He went to help.

“That’s just the reality,” he said.

“How else can you possibly explain it?”