TRISHA Roberts is lying in bed in the dark. Her sleepy face is lit by the glow of her computer screen.

It is 2am, six months into her young husband’s deployment to Afghanistan. The couple are talking on FaceTime. They connect almost every night.

But this chat is different to the others.

It is 8.30pm in Tarin Kowt. One moment she is telling Private Nathan Roberts their baby son is sleeping through the night; the next there is a loud bang, then bomb sirens wailing through Trisha’s speakers.

On her screen, she can see Nathan’s computer has been knocked to the ground. There is yelling and dusty army boots scuffling past the camera, crooked at foot level. Then silence. Except for that siren.

Nathan and the others in the room have dashed to a bomb shelter.

A few minutes pass, then Trisha switches off her computer. If her husband is about to be killed, she doesn’t want to witness the explosion that will take him.

She is wide awake now. Soaked with dread. Half an hour passes. Her video messages pip again. It is Nathan. He apologises for the hasty exit. “It happens almost every day,” he tells her. “No need to worry.”

Nathan wasn’t on the front line in this war. He didn’t patrol enemy territory. He was 25 then and a storeman in the Australian Army. Yet he was never completely out of danger. It was Afghanistan. They all knew nowhere was safe.

But when his tour ended, Nathan was a broken soldier. And nobody had warned Trisha that the war might follow him home.

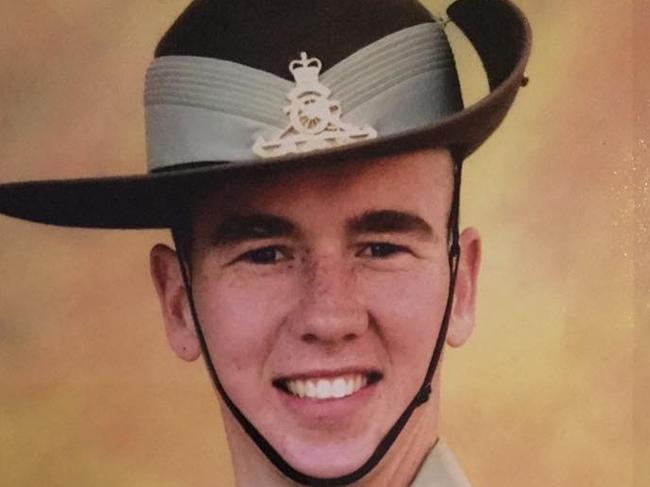

ON MAY 4, Private Nathan Roberts took his own life. He was 28.

He had already tried six times. Some of them were serious attempts. He’d had many admissions to Townsville’s military hospital.

Trisha says Nathan shared hospital wards with soldiers having wisdom teeth extracted and broken bones mended.

The place didn’t seem set up to deal with the serious mental illness and injury that was threatening (and was to take) Nathan’s life.

And when he was home, Nathan’s condition was something that Trisha — with a new baby to add to her three other children — was not equipped to nurse. Not one bit.

IN Darwin two years earlier, Bonny Perry was just as desperate for answers. Her husband, Flight Sergeant Andrew “Mung” Perry, was one of those strong military types that everyone respected.

He was a sharp shooter. His juniors looked up to him. His seniors knew they could trust him. And he’d switch to class clown when his men needed it. He was in the RAAF, an airman of 24 years.

When he was deployed to Afghanistan in 2013, he was team lead sniper. He had 82 troops under his direct command. Together their job was to secure the Tarin Kowt air base.

Bonny remembers Mung’s calls home to her. “What was killing him on the inside was the fear of someone dying on his watch,” she says. “He was petrified of having to make that call to someone’s mother to say her son had been killed.”

Mung was living on four hours’ sleep a night. He was micromanaging and he was caving under the pressure. He came home early to Darwin airport, under escort. They were worried even then that he was suicidal.

The man Bonny welcomed home was not the one she had farewelled seven months earlier. He’d lost so much weight he needed a new wardrobe of clothes. He was distant, depressed and anxious.

Now he was back, she didn’t know what to do with him. She’d been in the RAAF for years herself, but this was new. And there was no support for her, a wife handed the complicated job of putting Mung back together.

The RAAF tried to keep him working for nine hours a week. But his fragile state meant he couldn’t work in the armoury. Bonny reflects it did more harm than good.

Mung became an airman without a purpose. A sniper without a gun.

At his funeral, tough military men cried. They mourned the loss of their fallen colleague. But it was more than that. Where would this end?

One highly ranked officer who spoke at the funeral said what they were all thinking: “If it can happen to Mung, it can happen to anyone.”

THESE things are never simple. Every man and woman prepared to sacrifice their life for their country takes with them their own set of strengths.

The Australian Defence Force recruits them and trains them to be some of the most revered military people in the world. They go off to war and live through battle, spend months on high alert. Sometimes they kill. It’s so the rest of us back home don’t have to.

The Jenkins family, it is fair to say, is doing its bit for Australia. Sue and Peter have three sons. Their youngest is considering joining up.

In mid-February they farewelled their oldest son, deployed in the army to the Middle East. It was his first tour.

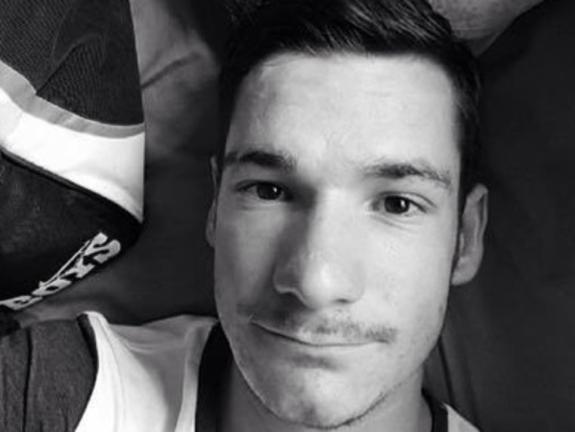

But less than a week before that, they laid to rest their middle boy, Shaun.

Shaun will be forever 24. He passed away from suicide, when he was still serving, in Townsville on January 31.

The man who came home from Afghanistan in 2014 after seven months was different to the one who went away. He returned with memories that he couldn’t shake.

One that kept returning was an accident in a Bushmaster armoured vehicle he was driving. The road collapsed under the vehicle and they plummeted 50m down a cliff.

They were all injured, at least one of them seriously. It wasn’t Shaun’s fault, but he blamed himself for his mates’ injuries.

He diagnosed with PTSD after he returned to Australia. Sue and Peter noticed he was more withdrawn.

“We tried to reach out to him. But he wasn’t reaching out to us for help. He wasn’t prepared to talk about it,” Sue says.

They are desperate to get the message out there: PTSD isn’t a weakness; veterans that are hurting are not alone.

“These guys need mandatory psych tests, then follow up psych tests. They should attend seminars, with support people who need to know what to look for. And an organised buddy system,” Sue says.

“We need to try harder, because we can’t lose any more, and the people who need the help most aren’t in the position to help themselves.”

“James” also kept his experiences close to his chest. He didn’t let on to his country town family what he lived through in military service.

He was the 25th ex-military man whose family the Sunday Herald Sun contacted in this investigation. He died in the past two years from suicide.

His dad, “Ross”, didn’t want James drawn into this story. It was clearly hurting him.

Ross is on the phone, quietly listening to the statistics. As of that day, he is told, 27 ex-service men and women have died by suicide this year.

It surprises him, how many come home from war and end their military service psychologically damaged. He interjects, with the command of a man who also used to serve.

“Thanks, but the military made a man out of my son. His problems were about money and women. He wasn’t even properly deployed.”

Properly deployed. So did he serve overseas? “It was only East Timor,” says Ross. “There was no real action. Plus, it was a long time ago.”

James, it turns out, was in the first wave of Australia’s involvement in East Timor. In the weeks after the conversation with Ross, the Sunday Herald Sun spoke to two veterans deployed with James in Operation Astute in 2006.

For weeks the troops were wired, primed for action. Part of their work was to mop up after the slaughter of innocents caught in the turmoil.

If Ross knew this, he might have thought differently of his son. It’s common for returned soldiers’ relationships to break down. It is not unusual to take 10 or 15 years for them to hit the low ebb.

But James doesn’t appear to have told his dad any of this. Veterans regularly shield their closest from the things they see. So when families have the chance to help, they can’t.

And when their sons and daughters are gone, they don’t know why.

JASMIN Carmel wishes she knew before what she knows now. Of course, she still has three sons, she says. But only two are left.

Jarrad Brown was her oldest boy. He was good-looking and tall with broad shoulders when he went off to war. He was protective of his mum.

She, like most of the families, would prefer to privately grieve her boy. But she speaks out knowing Jarrad would want it. If it saves one family from the pain she’s lived since he left, then it’s worth it.

Jarrad was a respected corporal. He went to Iraq in 2007 and Afghanistan in 2010. Jasmin remembers her pre-teen son watching the TV when the Twin Towers crashed down in 2001. It ultimately led to his service in the Middle East.

He told his mum very little of war. Just light stuff. “He didn’t want to worry me.” But things over there were serious.

In July 2010, Jarrad was pallbearer to one of the 41 Australian soldiers who died on Afghan soil. Private Nathan Bewes was killed by an improvised explosive device.

The pair were close friends in a tight-knit group of about 12. The two men trained together for six months in pre-deployment. And they spent time on the ground over there.

Jarrad was back in Australia, working fly-in fly-out in Port Hedland, WA. The mining companies like employing veterans: they are used to living away from family, they work hard and they do what they’re told.

When he returned to Queensland on weeks off, he seemed quiet.

“I saw it in his eyes. ‘I’m all right, mum,’ he’d say. Then deflect attention to other people,” Jasmin recalls.

He wasn’t all right. But Jasmin didn’t know what to do. She didn’t know he was so traumatised that he would take his own life. He passed away on December 5 last year.

Jarrad may have set foot back in Australia, in a way that his mate Private Bewes did not. Still, everybody agrees, the war took them both.

“We can’t lose any more. They bring them back to us and we have to fix them. We don’t have that training,” Jasmin says.

“I plead with these men and women, if they are hurting, to reach out for help. There are places, but you have to reach out.”

VETERANS aren’t rich, but they’re generous. Everybody wants to help. People start counting the ex-service organisations designed to support veterans and they give up at 200.

Online Facebook volunteers scour hundreds of ex-military pages for suicidal men and women. Some of these welfare volunteers stay connected far into the night. Many are battling their own PTSD.

They have a name for the distress messages: Last Posts.

Overwatch Australia is an online infantry battalion set up to react to people in crisis. One of the founders, Mark Kirwan, says the group now acts on 300 Last Posts each year.

He describes one occasion. Someone saw a post on Australian Warfighters’ page. He was getting his affairs in order and planning to “check out” in two days.

“We made inquiries. We couldn’t get a person on his doorstep within 30 minutes, so we called the police to do a welfare check. He’s still with us,” Mark says.

“There is no doubt in my mind that if it wasn’t for these calls, the number of ex-service suicides each year would be much higher.”

Nick and Karen Forster-Jones see their own share of troubled veterans. They’re among the hundreds — from large, well-funded organisations to individuals — trying to help fill cracks that our veterans are falling into. Scores turn up on weekends to help at their Diggers Rest in the Sunshine Coast hinterland.

A cluster of little units and camping patches is growing as former servicemen and women, and their families, head out to help. And, mostly, to recuperate.

Jasmin sometimes pitches a tent in the Diggers Rest clearing. There, she sheds tears for her son. At night she sits by the communal campfire. It’s a place where things can go unsaid but deeply understood.

Nearby is a veteran going back and forth on a ride-on mower. Work at the place is as much for therapy as it is to help create this oasis for troubled military minds.

In six months, more than 300 veterans and their family members came through. The place is relaxed and off the grid.

“There’s no book about how to get back into civilian life, no training,” says Rhodesian-born Nick. He used to serve here in 3RAR. He’s still awaiting a significant financial backer for the venture. Most organisations will wait a long time.

“In Australia, we don’t need to carry guns. It’s safe to go out at night. Somebody has paid the price for that,” Nick says, then gestures out into the dark from the campfire.

“All this is to thank these guys and girls who fought for what we have. It’s the least I can do.”

IT’S the sort of place Private Nathan Roberts and Trisha might have found some solace. And Trisha thinks that her husband might still be alive if more had been done by Defence to follow him up.

Besides, Trisha believes Nathan should never have been sent to a war zone in the first place. She says before he went away, the army knew he was mentally fragile.

Knowing he might struggle with the deployment, Trisha did her best from 10,000km away to keep Nathan in the loop of their young family.

Little Emrys was an early walker. His first steps were a little before he was nine months old. Trisha was torn. Within a week the three of them would be together on Nathan’s mid-deployment leave.

She resolved to keep it secret. Nathan had already missed so many milestones of his first child. As they settled into their hotel room in Queenstown, NZ, Emrys took a couple of steps. Trisha conjured up some excitement. And Nathan believed he was there to see his son walk for the first time.

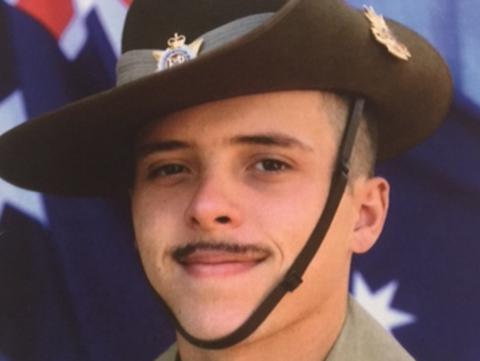

Private Daniel Garforth also felt that separation from his little girl. Although he never set his boot on ground in a war, his story is no less distressing.

Daniel signed up for the army at the age of 19. Within a year he appeared to be a bad fit for military life. His mum, Nikki Jamieson, says his posting to Darwin away from his toddler daughter in Brisbane weighed him down.

He signed up for four years and lacked resilience to survive what he felt was bullying by one of his officers in charge. When he tried to voice his concerns with a more senior rank, he was disciplined.

“He felt like he had nowhere to go for help. He was trapped in a place where he felt powerless,” Nikki says.

“From his diary entries, he wrote his faults were singled out and he was ostracised, belittled in front of his peers and colleagues. He was refused leave from regular duties to see his psychologist.”

Daniel was 21 when he took his own life. Two weeks earlier, he’d been on guard duty in the barracks. That night, he took a distraught call from the civilian friend of a suicidal female soldier on base. The friend was worried for the soldier’s safety.

Daniel told his mother his report to a senior was brushed off. And the next morning, the female soldier was found in her room. She had died from suicide. “He felt like he’d let her down. And his seniors should have been alert to the fact that suicide is a contagion.”

Nikki is a qualified social worker. After the death of her only son, she says she’s discovered the old-fashioned bullying culture in the military is still rife. Instead of exploring her legal options against the ADF, she decided to try to help.

She’s started her PhD into understanding what life is like for young soldiers in the army.

“I decided my absolution will be to find out why so many are dying,” Nikki says. “Then maybe the military can use my research to do more to stop it.”

HOW much research do they need? Spend six months at ground level with families and veterans and you’ll find the same problems mentioned independently, over and over. The bureaucratic systems are rigid, limping or broken.

The two most criticised government bodies are, unsurprisingly, the Australian Defence Force and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs — the ADF because it leaves service people and veterans high and dry; the DVA because its insurance company approach to approving entitlements is for some the nail in their coffin.

So strong is the anti-DVA sentiment in the grassroots veteran community that T-shirts are sold online saying: “The DVA: Giving veterans a second chance to die for their country since 1920”.

This is harsh. But for some it seems their reality.

Michelle Zamora’s little brother Dan Herps was a victim of several systemic problems. He died from suicide on January 19, 2014, aged 38.

“I wish I could have been stronger for you but I seriously can’t cope with all this pain,” he wrote to his sister in a final letter.

In the months before he took medical leave from the ADF, he’d started training for Special Forces. He described to her aspects of his training, including a terrorist interrogation module. That this was harrowing is not surprising. That there was no “debrief” is astounding.

“They were basically teaching him how to be a terrorist target and not reveal national secrets. Torture training even,” she says. “But when they sent him home there were no follow-ups, no calls. His eyes were different. He was hurting, but telling me he didn’t want to talk.”

At his funeral, one colleague who served in border patrol with Dan during the height of the asylum seeker boat arrival crisis said it was distressing for the servicemen and women on board.

“They were basically told by officials to ‘stand down’ if babies were thrown into the water. He was a father. Nobody should be expected to watch a child swallowed up by the ocean,” Michelle says.

Dan was diagnosed with PTSD. The treatment he received was inadequate, she says. Psychiatrists prescribed him medication linked to suicide and banned in the UK and the US.

When he started his application for DVA entitlements, he became swamped. Michelle, a business executive, says the independent systems for the navy, ADF and DVA seem designed to send even the mentally sound into a fury.

“Dan took on an advocate a month before he died. His claim hadn’t gone very far. By the time I started the process for compensation for his widow and son, I was told everything had been lost and I had to start again,” Michelle says.

“I had to go through hundreds of emails from Dan, which he’d sent me over 10 years, to help his case. It was appalling.”

From the start to the finish, Dan seemed let down by the systems in the nation he signed up to serve.

And Michelle has no doubt: “If the right services and support were in place, Dan would still be alive today.

“Dan joined the navy to protect this nation, and to serve the community. However, the systems and services are not set up to protect them. We have a responsibility as a community to bring our defence force home safely and to provide them with the care that they deserve. This is not happening.”

PRIVATE Nathan Roberts seemed happy when he first came back from Afghanistan. He slipped back into family life. At first, he was an attentive father and partner.

Trisha became pregnant again. Their second was a little girl, Mabyn. It seemed that the extra stress every newborn brings opened Nathan’s wounds. Nathan couldn’t mask his depression.

He would jump at loud noises — a bang from the kitchen, a car smash on the corner of their street.

And it’s common for returned troops to become fixated on being busy. If they try to unwind, it incites the demons inside their heads. (Mung’s distraction was fishing and house renovation. “He could never really relax,” Bonny says.)

Nathan took to cross-stitching. He would sit in the armchair for hours each day, next to the natural light from the window. He would go for days without eating or drinking. And he didn’t sleep much.

Trisha didn’t know what to do. There was no advice from the army, no phone calls to check how she was going. Even after he died, the support was scant, she says.

The joy of their little army chapel wedding — organised with military precision in 10 days flat so Nathan could go to war a married man — seemed a long time ago. The man Trisha had married was different.

He was never diagnosed with PTSD. But Trisha is in no doubt that he was a war casualty. “To wake up for nights in a row for nine months to a bomb siren, worried about having bombs dropped around you. How can that not be fearing for your life ‘beyond the normal’?

“How can you not come out of that unscathed?”

NATHAN Roberts’ size eight army boots are displayed with his other precious army things on a bookshelf beside the TV.

Soldiers are issued replacement boots at the start of every year. Nathan never wore his; he was too troubled to return to work.

But sometimes Emrys pretends to be a soldier and slips his feet into those boots. They reach up to his bum.

Mabyn was 13 months old when Nathan died. Trisha knows she’ll never remember him. Their son probably will.

Even at his most troubled, Nathan would tell Emrys each night that he loved him to “the moon and back”.

Now, the little boy tells people his dad has gone to the moon in a rocket ship.

“Some days I don’t think he really gets it,” says Trisha. “He doesn’t really understand that this time his daddy won’t be coming back.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Thousands of Aussies want inquest into Louisa Ioannidis’ death

Calls for an inquest into the death of 24-year-old Louisa Ioannidis, who was found dead in a Melbourne creek, have grown after new evidence was discovered.

‘Silenced and sidelined’: Broken justice system fails victims of crime

Victims of violent crimes and sexual assault say going through Victoria’s “injustice” system was worse than the crime itself, with some questioning whether they would ever report another crime.