ANDREW Hastie remembers the Apache gunships swooping in over the hills, high in the clear blue Afghanistan sky.

The then 30-year-old was a captain with the SAS and, as troop commander, had called the Apache helicopters to take out two Taliban members loitering with a pair of donkeys about 1200m away.

The Australians had intercepted communications from the pair organising an attack on the Black Hawk helicopters due to pick up this group of seven Aussie soldiers, who were visiting a remote police post in Taliban territory.

Across the valley, two other figures with donkeys were gathering firewood, but Hastie didn’t pay them much attention. They were clearly civilians, and were hundreds of metres away from both the police post and the Taliban pair.

ANDREW HASTIE: WHY I HAVE SPOKEN ABOUT TRAGIC SAS MISSION

The civilians were Toor Jan, 7, and his little brother, Odood, 6, members of the nomadic Kuchi tribe, who had gone out from their village with their two donkeys because the firewood would help their family.

The tiny brothers would be dead minutes later, killed in a catastrophic accident of war that saw the Apache helicopters fire on them instead of the Taliban targets. And Hastie, career soldier, would rethink his entire focus on war and democracy.

But at that moment, Hastie was focused on the two Apaches, sophisticated American killing machines fitted out with Hellfire missiles and 30mm cannons, coming in hard on his right.

He turned his attention to the Taliban pair but when the noise of the cannons began, the rounds hit not the Taliban, but the two figures across the valley.

“I saw it all,’’ Hastie, now the Liberal MP for Canning, in Western Australia, recalls to the Herald Sun.

War is a miserable enterprise”

“I remember looking at the target, and then hearing the guns fire and then the rounds splashing 600m away and thinking, ‘what the heck, that is not at all, that is not the target’.

“Okay we’ve got a problem. Instantly I just thought, ‘here we go, civilian casualties’.

“I just felt sick. My stomach just dropped away and I remember as well thinking ‘you’ve got a job to do, you’re in command, you’re going to have to put your emotions aside and get on with it and find a way to somehow provide assistance to these civilians, extract our call sign and then report the incident’.’’

Hastie has never spoken publicly about the incident, which happened almost four years ago.

But he has agreed to speak now — reluctantly — because he accepts that as an elected representative, the public has a genuine right to know about the incident and his involvement in it.

He says the deaths of the two children is something he still thinks about regularly.

He recalls the two Taliban members disappearing as the Apaches opened fire, and one of his Australian troops urgently telling the Apache crews they’d hit the wrong target.

“They continued orbiting in the air, I’m sure they were feeling just as terrible as we were. Probably worse,’’ he says.

“I was thinking, ‘this is not how I imagined things to start in my time in Afghanistan. This is a nightmare’.

“I felt — as a young officer you want to do the best you can, you want to get results — and I just felt any ambition I’d had just flow out of me at that point.’’

The emotional fallout from the boys’ tragic deaths would set Hastie on a path out of the military and, later, into politics, as he rethought his belief in how liberty and democracy could be established in the ancient, complicated cultures that existed in Iraq and Afghanistan. He came to the conclusion that “democracy at gunpoint’’ was not the way.

“For me, it proved that culture and geography (are) decisive in the formation of societies and political institutions. Building lasting, trusted institutions takes time, generations of stewardship and public virtue,’’ he says.

“It was arrogant to think we could build a mirror image of ourselves in foreign lands. (The boys’ deaths) underscored the gap between our aims and reality.

“The two boys who perished were bystanders in this larger struggle. I was humbled and chastened by this experience. War is a miserable enterprise. I remember saying to my boss: ‘I didn’t come here to kill kids’.’’

Andrew Hastie with tribal elders in during his 2013 deployment. His job was to help provide force protection for the mentoring work by the coalition trying to oust the Taliban and rebuild Afghanistan

FEBRUARY 28, 2013, started as a regular day, if any day in a war zone can be considered regular.

Hastie had been in Afghanistan a week with Special Operations Task Group Rotation 19. It was his third visit to the country and his second tour of duty.

Their main job was to provide force protection for the mentoring work under way by the coalition of countries trying to oust the Taliban and rebuild Afghanistan. This meant targeting and taking out the Taliban leadership, helping to support the building of institutions such as schools, and trying to carve out some space for the new Afghan Government to govern.

“Our job pretty much was the stick. The carrot was the mentoring piece, the aid that was delivered through DFAT (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade), also there at the time and other NGOs (non-government organisations). And we were the stick that kept the bad guys back,’’ Hastie explains.

Hastie gathered six of his men and headed to a remote police outpost in the district of Shahidi Hassas, in Oruzgan Province, flying in from the base at Tarin Kowt in two Australian Black Hawk helicopters, with the American Apaches providing cover.

“It was an Afghan police outpost in a fairly dangerous environment,’’ he recalls.

“It was surrounded by Talibs.

“This valley system, which was once controlled by the coalition presence, was now left to the devices of the Afghan police who were isolated, alone, with low morale. So we flew out there to say, ‘we are the new Australian guys, we are here to support you’, build a relationship face-to-face, supply them with some water, some Red Bull, which is good stuff to trade with in the developing world, ammunition, some batteries, all those little things that just make the difference as a soldier.’’

The outpost had been attacked before, although not that day.

“Five months earlier, six months earlier, one of the SAS officers had been shot in the leg in a big gunfight, helicopters had almost been shot out of the sky with RPGs, it had been a big gunfight in that area so it was rattlesnake country. It was dodgy country, badlands,’’ Hastie says.

“The outpost we were visiting was built up high on this little knoll. It was exposed, easy to snipe at from the green zone, easy to fire rockets or RPGs at, but it commanded a pretty good view of the valley so it was chosen for that reason.’’

Hastie and his men were “travelling light’’ because they weren’t doing a patrol. He had 10kg of gear on, his full kit of body armour, and he was carrying an M4 carbine rifle — accurate to about 400m, and possibly up to 600m, if you were an exceptional shot.

The seven or eight Afghan police officers welcomed the Australians and their supplies into the outpost.

“We had a chat, they showed us the position. We sat down for some chai tea on a nice red rug, chai tea of course in these glass cups with a heap of brown sugar or white sugar at the bottom, a very sweet taste.

“We built rapport. They were glad to see us, grateful for the ammunition, the batteries, what we’d brought with us.

“We started getting intercepts that the Taliban were preparing to fire rockets at the base, and specifically that they were preparing to fire rockets when our Black Hawk helicopters returned to pick us up,’’ Hastie says.

“They were co-ordinating on their comms system to launch an attack, a direct-fire attack against us, which posed a considerable threat to both personnel and equipment.

“I was given, using — I can’t go into the details — but using the technology we were able to shoot a bearing to the people co-ordinating it, the eyes and ears of the Talibs who were readying a rocket, it sounded like they were getting RPGs ready.

“They were moving around us in the open ground and calling in our position, talking about who was there. Because of the open ground we were able to clearly identify them, the grid reference, the distance from our position, they were showing hostile intent.

“Under the rules of engagement at the time, we had authority, I had authority, to use lethal force to neutralise the threat.’’

Hastie says he could see the men with his naked eye, about 1100m or 1200m away, beyond the reach of small arms fire.

With binoculars, he could tell they were adult men, wearing what he describes as “dish-dash-like, Afghan wear, just the usual clothes that males wear’’.

“(They had) two donkeys, firewood, moving at an amble, in fact too slow, obviously too slow because they were obviously co-ordinating and taking their sweet-arse time to get around.’’

Hastie says he was “provided with an option to engage them with lethal force using the Apache helicopters”.

“And I thought, ‘yes, that’s a good option, but you don’t take life lightly’.”

He considered his legal position and believed he was justified in calling in the Apaches, given the men’s hostile intent picked up on the intercepts. He also knew it would send a strong message to any other Taliban fighters considering attacking the Australians.

So he sent his men back to double-check all the information — the intercepts, the intelligence, the locations, the grid position.

“They did all that and then I gave permission for one of my guys to start talking the helicopters on (to) the target.’’

Almost four years have passed. Hastie has resigned from the SAS, fought a by-election and a general election and has been a member of the federal parliament for more than a year.

But he remembers everything that happened next.

“A sunny day, a cloudless sky. It was February so there was still snow on the peaks, the rivers were starting to flow with the melt, the air was still crisp and actually cold when flying on the helicopters.

“The air smelt of firewood, spice; it’s this very enchanting smell, whenever I get a whiff of it I just go straight back to Afghanistan.

“We could see people about 600m away, well outside the target, well outside any sort of danger area in relation to the target.

“We weren’t even looking in their direction. They weren’t even part of the picture. They weren’t a consideration. I didn’t consider them a threat.’’

One of Hastie’s men verbally instructed the Apaches to target the Taliban pair, describing the men, the terrain, their grid reference, the reasons for the decision to engage them and, finally, gave Hastie’s initials to the pilot and gunner — AH, or Alpha Hotel.

“It means I take responsibility for the engagement,’’ Hastie says.

He turned his eyes back to the Taliban fighters after seeing the two Apaches come in over the horizon.

“In my mind’s eye, I just remember them being over the hills at some point, then as we started talking them on, as they were starting to acquire the target, I remember them orbiting,’’ he says.

“As I looked at the target they were out on my right-hand side, up high, not too high.

“I’ve done my own internal checks. I’ve double-checked everything. I can’t hear the pilot and I can’t hear the gunner in the helicopter but we have done all our ground checks and we are all happy that we have a legitimate target, we have a legitimate threat and we are very, very confident we have the right people in our sights.’’

The trigger is given — “clear hot’’ — and the Apaches open fire. They hit the wrong people.

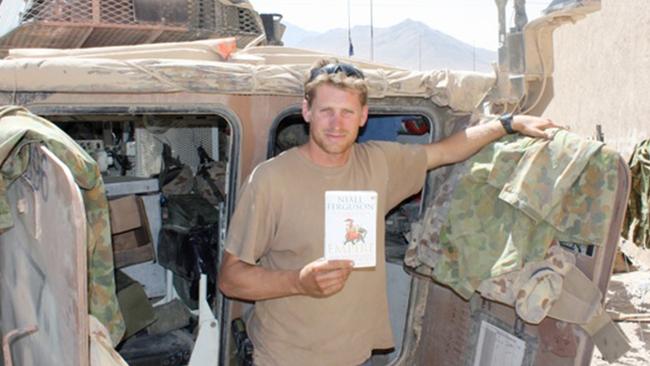

Andrew Hastie in Afghanistan in 2013. He recalls he could see the men with his naked eye, about 1100m or 1200m away, beyond the reach of small arms fire.

IN the silence that fell when the cannons halted, a stricken Hastie felt an obligation to render medical assistance to the civilians, even though he knew it was a risk to his own men, and a probably hopeless exercise.

“I took four guys and two or three Afghans with me, and we had people remaining at the outpost as well because it would be important if we came under fire to have guys with a firm hold back in the base who could still co-ordinate things.

“I decided at this point it was worth the risk of going out there, given that we had dispersed the threat.’’

The men moved quickly using a cluster of compounds for protection from ground fire, covering the 400m distance to where the two civilians had fallen.

“I got close and I still remember the clarity of the sky, very blue, I remember the mountains behind, but the lower I looked to the ground the more hazy and dusty and yellow it looked.

“I remember this yellow hue over the whole situation, then seeing two small bodies, and I instantly just thought, ‘these are small children’. And my heart sank.

“I thought they were dead straight away. But we went up and we made sure that there was nothing else we could do. We hoped they were still alive, but they weren’t.

“My medic went over and I remember him picking up one of the boys, both boys, and moving them into a position where he could have rendered first aid and then looking back at me and saying, ‘mate, there’s no hope. There’s nothing we can do’.

“I just remember one of them being very tiny. They were Kuchi kids, or hill kids, so they were from a nomadic tribe so their standard of nutrition was quite low, so they were probably a bit smaller than average kids.

“That’s when I radioed back to the guys still up on the hill, in the outpost, and I said, ‘we’ve got civilian casualties, we’ve got two dead children’.”

Hastie knew he had to hold it together. He recalled his SAS training, where he’d been taught to ignore his emotional state (low, he recalls, and depressed) and do his job. Photographs were taken of the children, to later form part of the report.

Hastie organised for the Black Hawks to come and collect the Australians from the area where the children were lying, and from the outpost.

The boys’ older brother, Sayed Rasoul, then 16, later told the media that after hearing the noise of the helicopter fire, a group left the village to investigate. They found the tiny, broken bodies of the boys where they had fallen, and took them to be buried.

We’ve got civilian casualties, we’ve got two dead children”

Hastie and his men continued to another Afghan army compound, a decision Hastie now regrets and says, with hindsight, should have been cancelled.

They then headed back to the base at Tarin Kowt, where Hastie’s boss, the major who was squadron commander, was waiting when the helicopter landed.

“I said, ‘boss, we’ve had a civilian casualty incident. I gave permission to engage two targets, legitimate targets, and there was a mistake and two children have been killed. If you need my resignation, you’ve got it’.

“He said, ‘well, have a breath, go up to the command centre and we’ll talk about it when we go up the top. Let’s go through the full process. The quick assessment, the investigation process and let’s follow procedure’.’’

Hastie felt deeply unsettled. He barely nibbled at food over the next 24 hours. He could not close his eyes: “I didn’t sleep much in Afghanistan at all, to be honest.’’

He thought and rethought through everything that led up to the incident.

The Australian Defence Force sent an investigator from Australia. NATO conducted an investigation. The Afghans got involved. Hastie fronted US military lawyers and explained what happened, over and over.

The ADF review found no criminal culpability. Hastie will not say what the outcome of the report was, other than the Australians were cleared of blame.

The incident was raised during the Canning by-election, when he first sought election to federal parliament.

“I am very, very hesitant to talk about it,’’ he maintains.

“Two children died.’’

If February 28 had never happened, it’s possible Hastie would still be a soldier and not a member of parliament.

The scarifying experience, he says, “confirmed my political transformation. Societies aren’t changed from above but from below — by people. We entered the valley with good intentions and left a grieving family in our wake”.

The experience confirmed for Hastie the doubts he had about an outside military force being able to enact change in Afghanistan, with its complicated tribal and religious structures, and deep history of conflict.

“We had limited awareness of the community, their lives, of their kinship, their hopes and aspirations. It must have seemed absurd for us to fly in and then leave just as quickly. We were a metaphor for big, unaccountable governments, as far as the Afghans were concerned.

“This was the central challenge of Afghanistan: we had an important job to do as an alliance partner of the United States and NATO, there was an enemy who was deeply opposed to human rights and freedom but it seemed like a war without end. Aussie Diggers gave their health and lives in Afghanistan and we should honour their service. It was noble.

“But we shouldn’t shy away from discussing the policy framework in which they had to fight. I learned that policy in Canberra looks a lot different on the ground for Diggers on the other side of the world. Politicians need to constantly explain the reasons, the goals for using military force.

“I’m proud of what we achieved. We removed some enemy combatants who fired rockets at our base or planned to drive a truck bomb through the front gates. I sleep very well now when I think of those operations.”

Andrew Hastie (centre) with comrades in Afghanistan in 2013: “I’m proud of what we achieved”

AS was usual with civilian deaths in that war, the ADF decided to pay compensation to the boy’s family.

It was either a few hundred dollars (according to then defence minister Stephen Smith), or a few thousand (according to Afghan officials). Either way, it doesn’t go close to ameliorating the pain of two little innocents losing their lives.

Hastie decided he wanted to face the family and apologise, and lobbied his military superiors to be included in the talks.

“The decision was made somewhere up the chain to pay the family reparations for each child and also go out and meet the family at an Afghan police base somewhere in Charchino (the district where the incident took place),’’ Hastie says.

The meeting was attended by senior Australian military officials, senior Afghani officials, village elders, and the boys’ uncle and brother.

Hastie’s efforts to attend were met with limited enthusiasm and he was denied permission.

“Initially, they wanted to keep the people involved in the incident away from the incident resolution. That sounds very cold and clinical language but I think that’s what they call it. They just wanted to keep us out of it, for emotional reasons, for psychological reasons, every reason you can imagine after an incident like that.

“My training from day one at ADFA and Duntroon emphasised taking responsibility for your actions as a leader. You don’t walk away.

“I spoke to the interpreter who was there on the day. The interpreter said to me, ‘where’s your body armour and your gun and your helmet, are you coming, or what?’. And I said, ‘no, I’m not coming. They didn’t want me to come’.

“He said, ‘no, you must come. This is part of Afghan honour. You’re responsible, you should be apologising’.

“So I went over to my boss and I said, ‘hey, I need to be on this, can I still go?’. And he said ‘okay’.’’

Hastie ran up the hill through the base, grabbed his body armour, rifle and helmet and jumped on to the helicopter.

He didn’t sit down or speak at the meeting, instead providing security on the periphery as the senior officers and family negotiated the financial settlement.

He waited for his chance to speak.

“Once the meeting had finished I stepped into the centre of the room with the uncle and brother and I said to them, ’I’m the commander, I was the guy who made the decision’.

“And I said, ‘I’m sorry, if I could take it back I would’.

“And that was all I could think of to say at the time.

“And then the interpreter relayed that and the uncle replied in Pashtun through the interpreter. He sorted of nodded and gave me a warm, sympathetic smile, and said ‘I forgive you’.

“And that was the end of the interaction. The older brother, Sayed, his face was a lot harsher than the uncle, he seemed angry but I think it helped him to be able to identify someone who was willing to say ‘hey, it was me’.

“And I didn’t mind that, at all.’’

My training from day one... emphasised taking responsibility for your actions as a leader. You don’t walk away.”

Going into the meeting, Hastie had been strained and hyper-alert.

“I remember walking into the compound being very on-edge and worrying. There were a couple of cars that were running and I was thinking, ‘is one of these cars, does one of these cars have a bomb in them?’.

“Just being very alert to everything and feeling like someone was out to get me, looking for a bad guy in every direction.

“That was more psychological than actual.’’

Once the uncle offered forgiveness, Hastie felt his anxiety ease.

“Once he said that, I kind of relaxed — I mean, you’re still in a war zone, you’ve still got a job to do, you’re trained to focus on security and trained to look for threats, you never let your guard down, you’re always vigilant — but it was just psychological and emotional ease that followed, which was a gift from him.

“A huge amount of relief, like a weight had lifted. It was just a very strange feeling.’’

Hastie believes being able to face the family and apologise, and receive the uncle’s forgiveness, is one of the main reasons he has not been stricken with post-traumatic stress disorder, which has hit a number of fellow veterans hard.

“I absolutely think so. I had to do the routine meeting with the psychologist afterwards, a week or so afterwards, and I remember saying, ‘look, I was able to apologise, I was able to see the family, I was able to take responsibility for my actions’.

“I didn’t hide anything and that allowed early healing from what would otherwise have been a fairly deep psychological scar, emotional scar. Quite traumatic actually.

“I count myself very blessed in that sense, in that unlike other war veterans from previous conflicts I was able to kind of make peace with a very significant incident in the space of two weeks.

“It was only because my boss made a split decision — and probably against his better judgment, thought ‘why not, I’ll let Andrew come along’. He’s an exceptional leader and made some tough calls on that trip. This decision prevented me from breaking down.

“The family were kind enough to shake my hand, the uncle was, and I remember saying to my boss afterwards, I think it was the same day when we got back, I said, ‘thanks for letting me do that, it was very important’.’’

Hastie says there are “two heroes’’ to emerge in this sorry and tragic tale — the boys’ uncle, who found it in himself to offer forgiveness, and Hastie’s boss, Major L, who was “incredibly supportive”.

“He said he’d step in front of traffic for us in providing support after the incident. I’d felt pretty alone up to that point but it was comforting knowing he was willing to accept responsibility for us as well. That was leadership. He could easily have put distance between me and him.

“The uncle who accepted my apology and offered a word of forgiveness gave me a tremendous gift. I remember the sun outside the building where we’d met seemed a little brighter. I felt the weight of the previous days lift in the helicopter as we flew back to Tarin Kowt.

“He gave me release and the opportunity to accept responsibility.’’

Hastie says he thinks about the two little boys “quite regularly”.

“Yeah I do. I do. It’s hard to let go. The older my son grows, the closer he gets to six and seven, the more I’ll think about it.

“It’s just the way it is.

“When I got back from Afghanistan and I used to teach kids church or Sunday school in the Anglican church I went to up in Perth, I had six- and seven-year-olds, and it just really hit me hard.

“I could see what they cared about, and I could see what little children at that age were like. “And they’re the last sort, the most undeserving of all, of that sort of thing. It hits home.’’

He also feels the boys’ deaths as a political responsibility.

“I have a much humbler approach to politics and government now. Before my experiences overseas, I was a young reactionary who saw political power as a tool to be wielded for good.

“But now I see the state as a support actor, and not the main protagonist in our lives. The state cannot give us any more freedom, that’s something we need to constantly strive for ourselves in our everyday lives.’’

Thousands of Aussies want inquest into Louisa Ioannidis’ death

Calls for an inquest into the death of 24-year-old Louisa Ioannidis, who was found dead in a Melbourne creek, have grown after new evidence was discovered.

‘Silenced and sidelined’: Broken justice system fails victims of crime

Victims of violent crimes and sexual assault say going through Victoria’s “injustice” system was worse than the crime itself, with some questioning whether they would ever report another crime.