EVERY surgeon makes mistakes, but when complaints mount doctors have a name for them — frequent flyers. This is the story of one such surgeon and the failings of a system meant to protect us all.

TREVOR Ewert copped all the nicknames — Wing Nut, Jug Ears, Dumbo, Taxi Doors, Flaps. There is no mercy among mates in country towns.

Yet he handled it with a casual shrug. Besides, his sticky-outy ears put him in esteemed company — James Hird, Adam Gilchrist, Prince Charles. Why should he meddle with nature?

He didn’t change, but times did. He had a son, Cameron, in the late 1980s, who also inherited the Ewert ears. It bothered the young boy as he grew. He found out there was an operation that could solve his problem.

At the age of about 11, Cameron roped in his dad to have their ears pinned back. They decided to do it together.

EXCLUSIVE: SURGEON ALLOWED TO OPERATE DESPITE COMPLAINTS

EDITORIAL: FAILED SYSTEM IS A SICK JOKE

There was no reason to worry. In mid-2000, the Yarrawonga pair booked an appointment with Albury-based ear, nose and throat specialist Roland von Marburg.

He was highly recommended. He was particularly good with children.

On November 30, 2000, Cameron was wheeled into the operating theatre at the Wangaratta Private Hospital. An hour or so later, Trevor followed his son.

It was the start of two nightmare weeks. Within hours, the pair complained to nurses about the tightness of the bandages that wrapped their heads. They were in excruciating pain, not what you would expect from what had been described as a “basic operation”. No painkillers would stop it.

For the first week they could barely sit upright. Once, Cameron fainted from the pain. Trevor’s wife’s calls to Dr von Marburg’s rooms got them nowhere. The bandages needed to be tight, they were told. The pair was to put up with it.

What was happening under the bandages was not pretty. Some of the flesh on their heads was dying. Their foreheads would need reconstructive surgery and skin grafts by specialists in Melbourne.

Cameron’s right ear was a mess. Parts of it had died from the pressure wounds. In the following years, he had at least eight procedures performed by the best plastic surgeons in the business at the Royal Children’s Hospital.

Success was limited. Now he wears his hair long to cover bald patches on the back of his head, scarring on his forehead, and the misshapen ear. His sticky-outy ears were surely preferable to what the surgery left him with.

The Ewerts do not believe they can speak of their experience to the Sunday Herald Sun. They cannot even say why they can’t talk. It is reasonable to assume they signed a confidentiality agreement after a compensation settlement with Dr von Marburg and his insurer. (County Court records show they started legal action against him in 2002.)

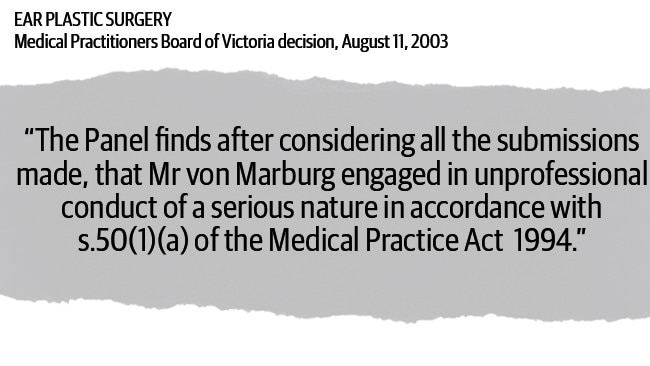

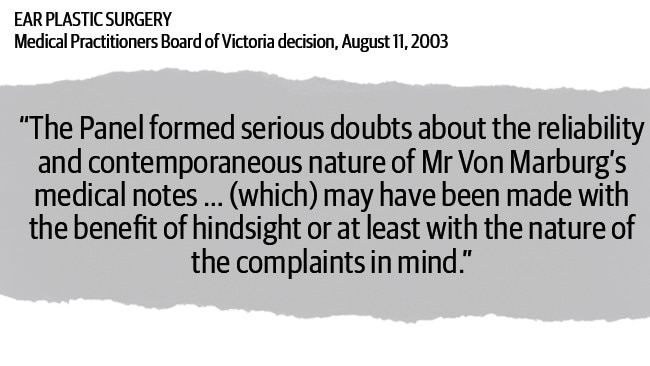

A Medical Practitioners Board of Victoria decision, dated August 11, 2003, was scathing of Dr von Marburg. The board determined he engaged in “unprofessional conduct of a serious nature”. He was reprimanded for his failures with the Ewert case and he was cautioned to “listen to his patients and take seriously their complaints of pain”. There was no further discipline. No suspension. No conditions placed on his practice.

Doctors make mistakes. Sometimes they make big ones. But, as several surgeons confirmed to the Sunday Herald Sun, the competent, professional ones know when to quit before they become what is known in the industry as “frequent flyers”. These outliers have complaint rates higher than what is normally anticipated for their fields.

The system set up to protect the community has been alerted often in the past 15 years to Dr von Marburg’s shortcomings. Yet some of his victims now believe that system is designed to protect the doctors, not them.

The Ewerts are frustrated they can’t talk. The Sunday Herald Sun learned of their pre-operation details from other sources. Just before Trevor turns down an interview in a phone call, he says: “I thought von Marburg was gone. That’s why we went through all that grief with the medical board hearing.”

Trevor was wrong. The surgeon was not gone. As far as big complications go, the Ewerts may have been Dr von Marburg’s first. But they were not his worst.

EAR specialists have plastic pull-apart models of ear anatomy within reach on their consulting room desks. They point to parts to explain how things work in there. Hearing is complicated.

And ears are delicate.

Surgeons operating on the inner workings must navigate through and around tiny structures — important nerves, minute bones, paper-thin membranes — that can be damaged with a slip of the instrument. Some procedures take tools to within a millimetre of the brain.

There’s good reason why GPs tell kids the smallest thing they should put into their ear is their elbow — and only then if it’ll bend that far.

One of the ear’s anatomical wonders is a chain of three bones in the middle ear. They are the smallest bones in the human body.

Margaret Brodie, of Wodonga, discovered the importance of each of these bones the hard way.

She believes that some time during the last three of five operations Dr von Marburg performed on her, one of those bones “went missing”. If he removed it on purpose, or even accidentally, he did not record it. She says he certainly did not tell her.

She’d had a series of infections in about 2000, which a previous surgeon had relieved by inserting a grommet. That surgeon had left the practice, so Dr von Marburg was recommended. He performed five procedures on her.

Her hearing did not improve. And after the third of the operations (the final three, as far as she knew, were for “clean-outs”) her hearing went downhill. She started to lose her balance.

She returned to her GP, who discovered a “massive hole” in her eardrum and an infection. A dose of antibiotics cleared up the infection and she was referred to another ENT specialist.

“They organised a hearing test, had a look in my ear and said they weren’t going to touch me — they wanted me to see a specialist in Melbourne,” she says.

A CT scan first established the state of Margaret’s ear anatomy. Dr von Marburg would have noticed the missing bone in a CT scan. It is unclear whether he organised one. Margaret believes he did not. If he did notice it, she says he did not tell her.

Associate Professor Robert Briggs is among the most respected of ear specialists in Australia. He is the head of otology at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital. Medical records show he replaced the little bone in Margaret’s ear with a titanium implant. She can hear better now.

But she had to retire years earlier than planned from her job in the public service. She couldn’t work because of her hearing problems.

She’s angry the trust she had in Dr von Marburg now seems so misplaced. And, knowing that other people have been damaged, she’s annoyed that the surgeon was never stopped.

She pauses. She’s choosing her words carefully. She and other former patients the Sunday Herald Sun approached are told Dr von Marburg is “lawyered up”. But, unlike at least a dozen who did not want to be interviewed, she wants the truth to be told.

“Isn’t it ironic that he can ruin our lives,” Margaret says, “but we’re the ones who are scared?”

THE trail of complications that have followed Dr von Marburg is well documented. They don’t just relate to surgery that damages hearing. There are claims of over-servicing — unnecessary surgery — and the wrong surgery for the complaint. There is surgery conducted contrary to widely accepted surgical principles.

And there are claims that Dr von Marburg’s post-operative care was regularly deficient.

The Sunday Herald Sun has learned of a little girl who suffered meningitis, which took away much of her hearing. She underwent five general anaesthetics for procedures by Dr von Marburg. ENT surgeons have subsequently said the operations never stood a chance of restoring any of her hearing.

Albury Wodonga Health is known to have had to deal with a patient from whom Dr von Marburg took an ear tissue biopsy — which the pathologist was astounded to see included brain tissue. The patient is understood to have suffered some neural damage.

And just this year an elderly man was left with partial facial paralysis when his facial nerve was severed during ear surgery. This is a recognised complication in surgery, but, as one surgeon stated: “It doesn’t happen if you’re competent.”

Complications can afflict any surgeon. But when the list starts to build — as it has for many years with Dr von Marburg — the system should be able to move in swiftly and act decisively.

It has not. And trusting and sometimes desperate people looking for relief have been harmed because of it.

PRIMUM non nocere. This is the guiding principle for doctors — it is Latin for “First, do no harm”. Dr von Marburg must have often felt that strain. He must have seen how devastating his serious error was for young Cameron Ewert’s ears.

At the time he was embroiled in the Ewerts’ medical board case, his practice was still young and growing. As was his family. He had several children to support, which would, in the ensuing decade, become eight.

The looming botched bat-ear case before the medical authorities gave him migraines. He self-prescribed and injected pethidine in 2001 to ease them. (That is prohibited.)

He admitted this in a case against him in the NSW Medical Tribunal. He became hooked on the opiate early in 2008. He admitted using it recreationally until October of that year.

“While the doctor originally denied his self-administration of pethidine, when he was faced with the overwhelming documentary evidence he conceded as to his addiction … Analysis of the doctor’s drug taking reveals he hid his addiction within false medical records of existing patients,” the tribunal document stated.

The tribunal did not hand down its decision until August 2012 stating the drug-taking had “turned him into a dishonest medical practitioner”.

Dr von Marburg was banned from prescribing, possessing, supplying, administering, handling or dispensing drugs of addiction. The matter resulted in him not being permitted to practise for a number of weeks.

It is also understood that at least one mandatory report was made to authorities in 2003 about his pethidine use, but this was never brought up in the hearing. The hearing was in NSW; the 2003 report was lodged in Victoria.

Dr von Marburg operated on another patient who is now suing him in the NSW Supreme Court. It is understood that victim’s case will be presented to NSW health authorities later this month.

When the Sunday Herald Sun approached the woman’s lawyer, James Sloan, he said she was unwilling to talk. Hers is now one of three civil cases known to be underway against Dr von Marburg.

The Medical Council of NSW attempted to remove his ability to conduct surgery in March this year, almost 15 years after the Ewerts’ botched treatment.

But he contested the interim ban by appealing to the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

So in August he was given back the right to conduct some ear surgery, sinus, vocal cord, thyroid and oesophageal surgery, as well as upper airway surgery such as tonsillectomies.

It’s believed no operating theatre in the area will take him. But still patients see him. Surgeons are wondering why GPs are still referring patients to him. They worry the community is not yet safe.

YOU can type into a website the name of any medical practitioner in Australia to find out if they have conditions attached to their practice. Most patients don’t think to do that when they’re referred to someone new. Doctors are in the top three most trusted professions in Australia, second only to nurses and pharmacists.

People need to have this trust because they are allowing somebody into places that could kill them. Or maim them at the very least.

Until March this year, the conditions on Dr von Marburg extended only to his banning from drugs of addiction. Now, there are 10 conditions covering four pages on a computer screen of the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency website.

His rooms are open on business days, in Kiewa St, Albury. The Albury Wodonga Ear, Nose and Throat Clinic has patients of all ages walk up its path and through its front door. As of last week, Dr von Marburg was still accepting appointments.

At his busiest, his consultation rate was well above the average.

He was far more willing than most to take a patient into the operating theatre.

He is believed to have had a surgery rate well above most ENT specialists’ standard 65 per cent.

“It’s very easy to decide to operate, but a wiser person will sometimes decide not to,” says a surgeon who has detailed knowledge of damage Dr von Marburg has caused.

His willingness to operate made him an attractive specialist at the Albury Wodonga Private Hospital. Busy operating theatres are good for business.

But a stretched public health system has a different measure. High operating and complication rates raise red flags. By 2011, those flags were flapping wildly. The series of events that led to Dr von Marburg’s resignation from Albury Wodonga Health in March 2012 are closely held.

AT the time, Dr von Marburg told the local newspaper it was a difficult decision to resign. “Although my public work is about 10 per cent of what I do, it’s become about 90 per cent of my headache,” he was quoted as saying.

In response to these statements, Dr Stuart Spring, who was the AWH chief executive at that time, says the case highlights one of the challenges for every health services manager, in public or private sector.

“They only observe a small part of a practitioner’s work and rarely what occurs in the doctor’s rooms,” Dr Spring says.

“While the rumour mill is often vibrant, establishing sufficient evidence of a pattern of wrongdoing is hampered by the small number of cases — all of which can be dismissed as ‘unusual and striking, but not the norm’.”

Sources have confirmed Dr von Marburg was given no choice but to leave.

It is known that on some occasions, the surgeon was conducting simple and short ear procedures but charging for more difficult, longer ones.

Other ear surgeons’ expertise was brought in to confirm this. Public hospitals record the instruments surgeons use during each of their procedures.

In some cases, the recorded list of instruments Dr von Marburg was using was for a $150, 15-minute grommet insertion operation.

But instead, he was charging for a $500, 45-minute myringoplasty — surgery to repair the eardrum and plug it with gelfoam.

An NCAT decision this year stated Dr von Marburg conceded he had incorrectly classified some of his procedures for the purpose of Medicare and other claims.

Medicare would not comment on whether it had received or was investigating any complaints about these incorrect classifications.

Soon after he was told to resign, four ENT specialists — two from Melbourne — reassessed Dr von Marburg’s 250 patients set down for surgery at the base hospital. They were asked to determine: Had he booked patients in for appropriate surgery?

The Sunday Herald Sun understands that about 170 of the patients returned for reassessments. Of those, about 90 needed surgery. And of those, less than half were for the surgery Dr von Marburg had originally booked.

“This is a terrible record,” a source in the profession says. “Even taking into account variations of judgment from surgeon to surgeon, there is no way that the amount should be so wildly different.”

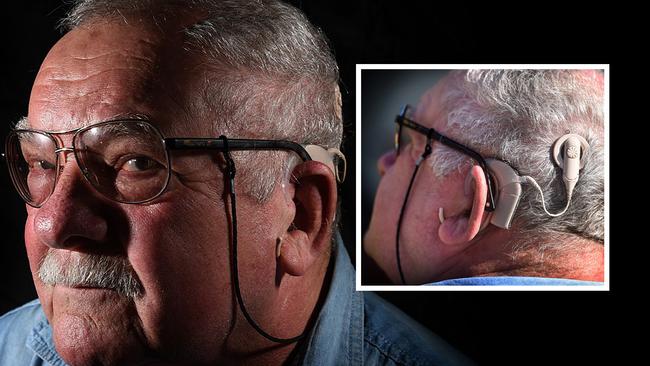

ROLF Kaiser was one of those who was later informed he did not need his surgery. It would have been good to know this before he went deaf.

The German immigrant came to Australia decades ago, but he was heartened when his GP referred him with vertigo problems in 2003 to a specialist with a German surname.

“He was charming,” Rolf recalls. He shook Rolf’s hand warmly on the first appointment. The 76-year-old felt he could trust him.

He says Dr von Marburg told him inserting grommets into his ears was likely to solve his problems. Soon afterwards he had one ear done, then the following week the other.

But within a short time he lost his hearing. He suffered a serious, life-threatening infection, a superbug that was treated but left him with no hearing.

For a man blind in one eye and with only 50 per cent sight in the other, this result was particularly devastating. Especially when he has since been advised by other specialists that inserting grommets would not have fixed his vertigo.

Rolf says he was referred to another specialist who said there was no way to return any hearing without a cochlear implant.

“Because of my age and the cost of the implant, I only now have some hearing in one ear. I’m very upset about this. I made a complaint to the Health Care Complaints Commission, but they were wishy washy in their response. It went nowhere,” Rolf says.

“Without my cochlear implant I am now stone deaf. My blindness in combination with my loss of hearing … I don’t have to explain my emotional distress.”

The Sunday Herald Sun also discovered a former female patient, booked into the Wangaratta public hospital for a nose operation. Dr von Marburg instead removed her tonsils.

Two weeks ago, an accidental misspelling of Dr von Marburg’s name in a County Court archive search threw up a surprise.

“Marburg, Ronald Von” was sued in 2002 by a woman who requested her name be withheld. She would not comment to the Sunday Herald Sun. Again, it is likely she signed a confidentiality agreement as part of her settlement.

Sources revealed that, before her operation, her consent form stated “tonsillectomy”. She is said to have seen the theatre nurse cross this out and replace it with the correct word: “septoplasty”.

But when she regained consciousness from the anaesthetic, she had a sore throat instead of a sore nose.

SIX surgeons have sat down with the Sunday Herald Sun in the past 12 weeks. They don’t want to be quoted. Each of them knows what can happen to whistleblowers in the medical community.

None of them say they would recommend any patient see Dr von Marburg for treatment or surgery.

The cohort holds itself to high standards. But it is difficult for a bad one of its own to be held to account. Breaking ranks — even anonymously — is rare.

Mandatory reporting laws were introduced in 2011. But commonly the investigative bodies must rely on the honesty of dishonest people, a source says. Forensic examination of claims is generally scant.

“Someone will have a complaint about them. The medical board will tell the doctor the nature of the complaint against them. They will say their actions were reasonable. They can make things up to back it. And it will go no further,” a surgeon says.

It is known that Dr von Marburg has made it clear to at least six medical professionals that he would take them to court for giving professional opinions about aspects of his poor practice. One senior surgeon is believed to have been called on to review about a dozen cases of his poor outcomes.

Many respected surgeons have indicated they would be willing to come forward to give evidence about Dr von Marburg’s surgical practice if subpoenaed.

Dr von Marburg’s legal bluster has sometimes worked. It has been easier for some practitioners instead to insist patients make the complaints themselves to the authorities. It is understood about 15 complaints from former Dr von Marburg patients have been made to the NSW authorities since March. Specialists have recommended many more patients take their grievances to the authorities.

The Medical Council of NSW says it can’t disclose “the specific circumstances leading to the action” in March against Dr von Marburg.

In recent years, the list of anaesthetists in the area willing or available to work with him dried up. So the Albury Private Hospital brought in one especially to work with Dr von Marburg.

Albury Wodonga Health’s former director of surgery, Neil Bright, has his own concerns about Dr von Marburg. He is familiar with some of the complaints made against the ENT surgeon.

He believes competent surgeons should curtail their own procedures that have bad outcomes above the usual rate.

He says if he had personally had findings against him by AHPRA to the extent of Dr von Marburg, he’d “pack up and go home”.

“I don’t think I’d have it in me to keep going. My concern is that he could make a comeback at some point,” Dr Bright says.

He says problem practitioners can be harder to identify in a regional setting.

“While the poor practice of a surgeon can be known, it is hard to get all the cases together to see the full picture. Often patients will go to a city to have their problem rectified, further diluting knowledge.”

Dr Bright says surgeons are generally reluctant to condemn for an adverse outcome in a single case. “I tell students anyone who says they don’t have complications is either not doing any work or is a liar,” he says.

“But if I had a reoccurring issue, if I had problems reported to medical boards, then I’d stop doing them. Apart from anything else, it’s not fun managing the problems.

“It’s about asking: what am I prepared to accept as a bad to good outcome ratio? What can I do to improve? I call it professionalism.”

MARYANNE agrees to meet the Sunday Herald Sun at an Albury café, at a table down the back so she won’t be spotted. She’s had conflict with Dr von Marburg before and doesn’t want to be identified. Maryanne isn’t her real name.

She says Dr von Marburg at first came across well. Competent and friendly. Her GP referred her to him for rhinoplasty to strengthen her nose and for sinus work.

In May 2008, in the middle of the months of Dr von Marburg’s “weekend” drug-taking, he put a hole in the cartilage between her nostrils — the septum. Prescription ointment he gave her to apply to the area only seemed to make it worse.

Last month, at the café, she rests her elbows on the tablecloth. She places an index finger slightly into each nostril.

“I know it’s a bit disgusting, but I want to show you this. My fingers are touching. I have no septum. It’s gone,” she says.

She says the specialist she saw after the damage was done told her they’d never before seen such damage to a patient’s nose.

While septal perforations are a recognised complication of nose surgery, Maryanne is angry at what Dr von Marburg did to her. She says he should never have been operating on her.

“I now have terrible hay fever and constantly suffer colds. Much of the mucous membrane in my nose to filter pollen or bacteria is now gone,” she says.

She’s been told the only potential way to fix it — major invasive surgery — has limited success. Maryanne will turn to that only as a last resort.

“We trust surgeons. And here in Australia, we believe the authorities will protect us from the surgeons who shouldn’t have our trust,” she says.

“So how is he still out there?”

-----------------------------------

CREDITS:

Investigation: Ruth Lamperd

Pictures: Tony Gough

Designer: Shane Luskie

Video: Craig Hughes

Producer: Michelle Rose

Thousands of Aussies want inquest into Louisa Ioannidis’ death

Calls for an inquest into the death of 24-year-old Louisa Ioannidis, who was found dead in a Melbourne creek, have grown after new evidence was discovered.

‘Silenced and sidelined’: Broken justice system fails victims of crime

Victims of violent crimes and sexual assault say going through Victoria’s “injustice” system was worse than the crime itself, with some questioning whether they would ever report another crime.