WENDY Joan Lange entered the small clothes boutique to buy herself a new dress. It was a two piece. Black and white. Elegant. It needed to be special, she told the shop assistant. It was for her husband’s funeral.

Except there was one small problem: her husband wasn’t dead yet. He would be found murdered one week later.

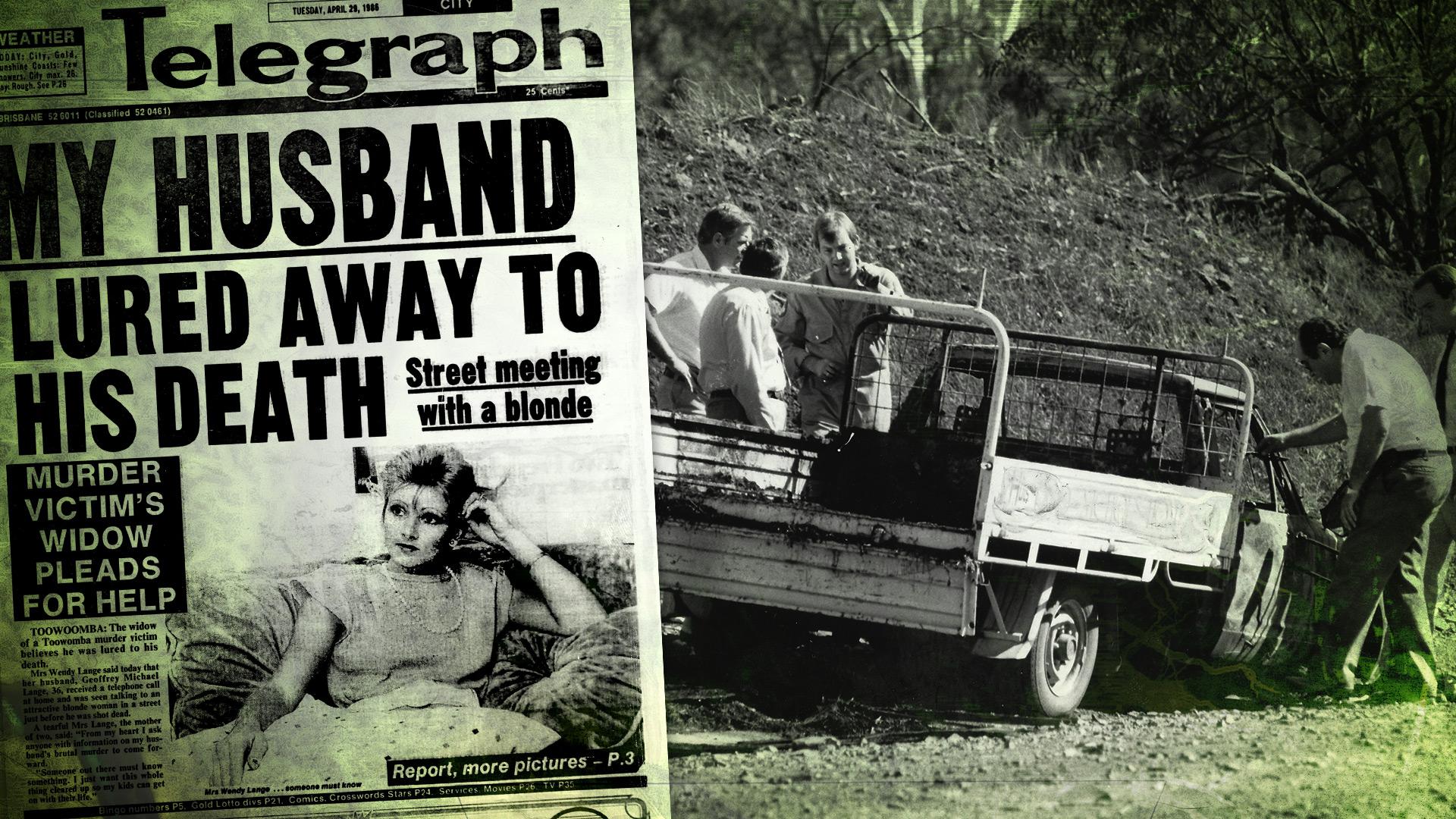

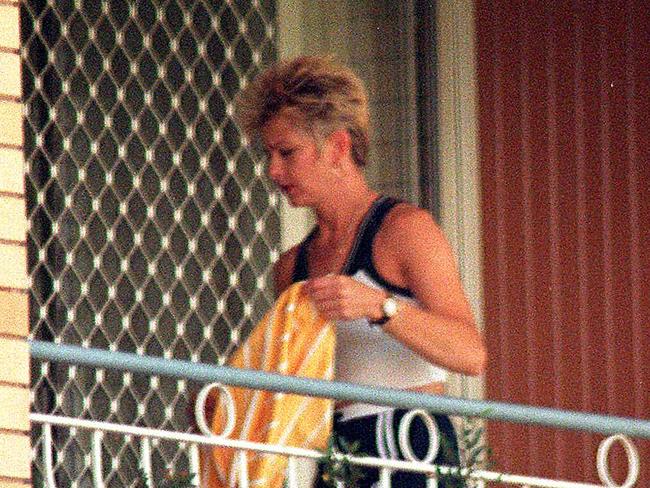

It was this seemingly cold and calculated scene that led the media to dub Wendy as Queensland’s own “black widow”.

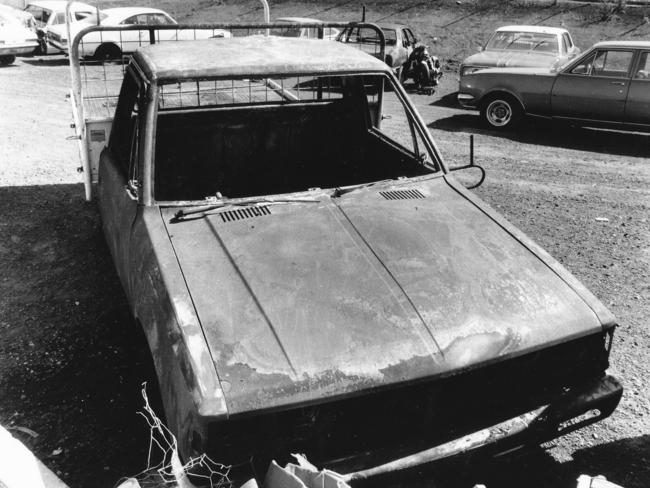

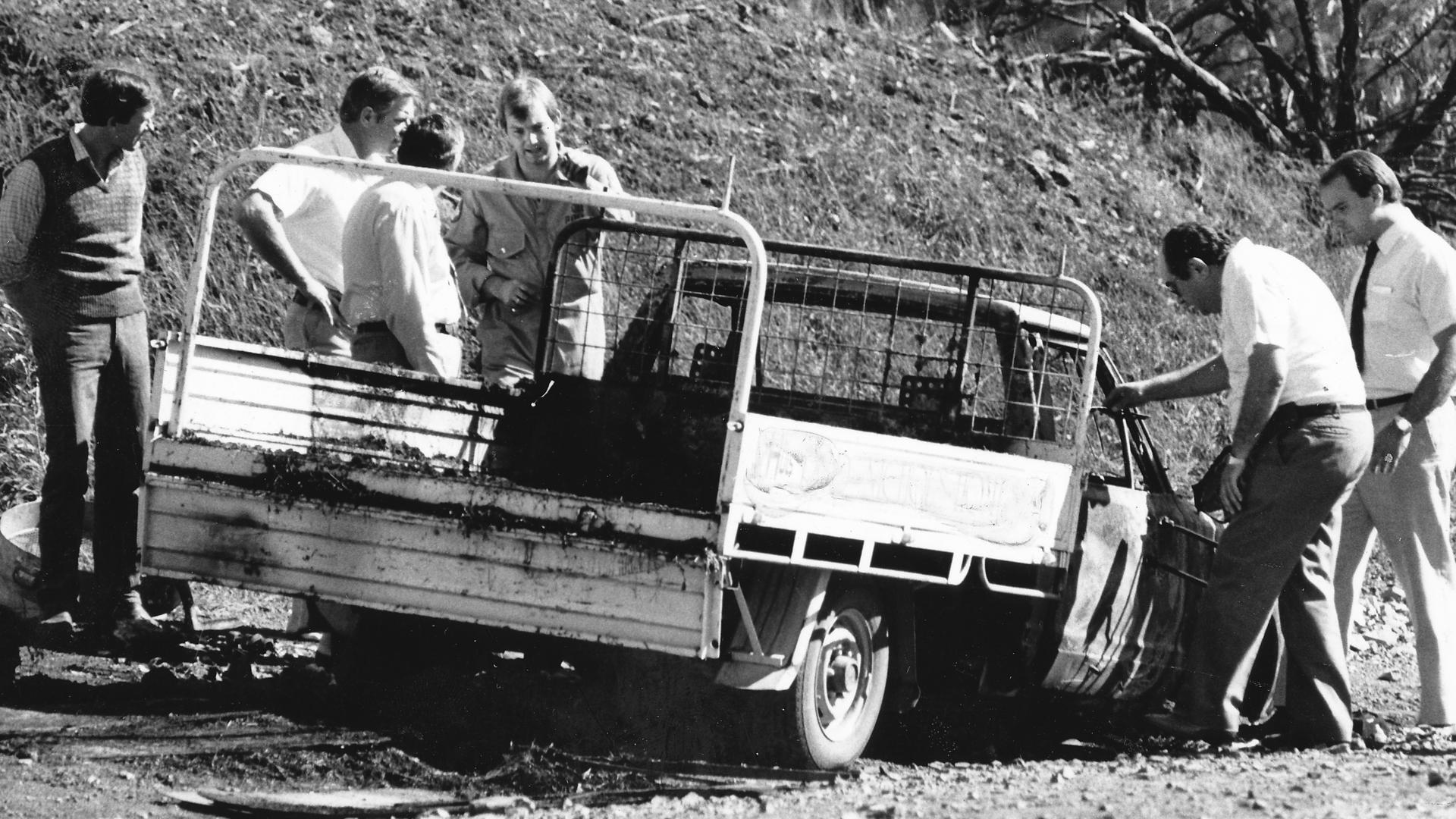

Geoffrey Michael Lange’s charred body was found in his burnt-out Datsun ute on the northern outskirts of Toowoomba on April 2, 1986. Police would later discover the killer aimed a .22 shotgun at point blank range behind Geoff’s left ear. The shooter looked away then fired before the rifle was tossed back into the cab of the tray at the dead man’s feet.

Geoff was said to have pleaded for his life before he was shot.

“What have I done? What have I done?” the 36-year-old asked his killers.

He questioned them about why they’d become involved.

“Only money, I suppose,” one of them was said to have replied.

Almost one month after Geoff’s gruesome death along a desolate stretch of Old Goombungee Rd, 15km north of Toowoomba, Wendy was charged with taking out a contract killing on her husband.

Brian Leslie Idiens and Dennis Wayne Garner had spilled their guts to police before her arrest, telling detectives they killed the building supervisor under instruction from his wife.

The two youths had become incensed after reading a front-page newspaper story about Wendy pleading for her husband’s murderers to come forward in the weeks following his death.

“You should see her,” Brian told his mate Dennis over the phone. “She’s sitting pretty up here. You should see her on the front page of The Telegraph.”

That was all the motivation they needed. Brian told his mate to tell police everything.

They separately explained to detectives that Wendy had paid them $10,000 to knock off her husband.

Dennis sang like a canary. At the cop shop he rocked forward in his chair, putting his head in his hands.

“What can I do if I had a little bit to do with it?” he asked the detective. “Would I be an accessory?

“I was there. Oh God, I was there. I am so sorry. I should have got out of it but I didn’t.”

Dennis told detectives Wendy first approached the pair about the hit on March 29.

Then, on April 2, they received a phone call from her. She told them to come around.

They caught a taxi to the corner of Hogg and Tor streets in Toowoomba before walking the short distance to the Wine Dr home that Wendy shared with her husband and the couple’s two young children.

Geoff was already unconscious on the ground when they arrived, Dennis said. He was heavily drugged. His wrists and legs were already bound. His eyes and mouth taped shut too. Dennis claimed he went to leave. But Wendy grabbed him.

“You’re in too far now,” she said.

The trio unsuccessfully used a syringe to pump Geoff’s veins full of air. When that failed, Dennis said Wendy gave them a rifle with two bullets.

She handed Dennis a jerry can full of diesel. Geoff was starting to come around by that stage. Dennis was nervous.

They managed to load Geoff’s body into the cab of the ute.

Dennis said he drove, stalling the Datsun twice before he even made it out of the street. Brian rode in the tray, which was full of hay bales.

When they arrived on that deserted stretch of Old Goombungee Rd in Cawdor, flanked by farming acreage on either side, Dennis said Geoff was already conscious.

An argument soon broke out about a botched drug deal between Geoff and Brian’s stepfather. Then a shot went off. But Dennis claims he wasn’t there to witness it. He only heard it.

When he got back to the ute, he found Geoff dead. Panicked, he doused the vehicle in diesel in an attempt to protect his mate. He set it alight before starting the long walk back to Toowoomba through the darkened bushland.

By November that year, eight months after the murder, the Toowoomba Supreme Court heard Wendy had often talked about killing her husband.

“I am getting rid of Geoff,” one of Wendy’s female friends said she confessed to her.

“I am paying them $10,000, and I won’t pay them for 12 months so it won’t look suspicious.

“They won’t use a gun. They will probably do something to the car like fix the brakes to make it seem like an accident.”

That same friend, who admitted to wishing her own husband was dead, testified that Wendy told her she had already bought a black dress for her husband’s funeral.

That transaction, at Georgina’s Boutique, happened on March 24 – just over a week before the murder. Shop assistant Narelle Wilson told the court Wendy had said she needed a “special” dress because her husband died.

“I asked her what happened to her husband and she told me he died of cancer,” Narelle testified.

But Wendy’s defence lawyer John Copley asked the jury to consider why she would be telling people about her husband’s funeral if she planned to kill him. He described that type of behaviour as being more consistent with a woman who was used to telling sob stories for financial gain.

Another witness, a Toowoomba service station assistant, said Wendy had bought $10 worth of diesel for the Rheem jerry can on the same day she bought the black dress. It was the same petrol tin found at the crime scene.

“When I told her there was 2cm of super petrol still in the jerry can she said not to worry – it would not do any harm to put the diesel in as well,” the witness testified.

But perhaps the most damning testimony came from Brian’s mother Robyn Idiens.

She said Wendy had come around to her home on the night before the murder asking for some tablets to help her sleep. Robyn gave her some Murelax – a tranquiliser commonly used to treat anxiety.

But she was hardly a reliable witness. It later emerged that Wendy had been writing letters to Robyn’s partner in Brisbane’s notorious Boggo Road Jail. She was trying to convince him to come live with her when he was released. The inference was that she was trying to steal her man.

It was only when Wendy took the stand that a motive for the murder started to become apparent. She painted a picture of a violent, disturbed man who suffered greatly after serving in the Vietnam War. She said Geoff often threatened her, including with a shotgun hours before he was found dead.

She said he’d been injecting himself in the kitchen with liquid from some capsules when their eldest son walked in. Wendy said her husband “lost it” when she tried to get their son to leave. He grabbed a rifle, storming back into the kitchen.

“He grabbed me by the throat and pushed me up against the freezer and tried to put the rifle in my mouth,” Wendy said. “He was saying he was going to shut me up for mouthing off about his dealings with drugs.”

Wendy managed to kick him in the groin during the struggle.

“It was the first time I’d ever defended myself in a situation like that,” she said.

That’s when she decided to spike his food, grinding the Murelax into Geoff’s mashed potatoes like she’d done so many times before.

“It was my only way of settling him down … slowing him down when he was on a high,” she said.

A short time later Geoff collapsed after trying to crawl up the hallway, drugged to the eyeballs with four-times the regular dosage of the tranquiliser. That’s when Brian and Dennis arrived.

After the trial, Geoff’s family came out fighting for him.

“Geoff’s name has been unjustly blackened by her lies,” his brother-in-law Rod Nichols told a journalist.

“What she said about him was a figment of her imagination since she was arrested. When she was arrested she started that drug story, which was lies from the start. She’s the only one who alleged all this about Geoff. The police never found any concrete evidence to back up her story.

“We just ask that the facts be made straight about the type of person he was. Not the type of person she painted him to be. We hope something can be done to repair the damage she’s done blackening his name.”

It could have been true what he said – except police investigations confirmed Geoff was prone to violent outbursts at home and in hotels. At the very least there appeared to be a great deal of substantial truth in what Wendy had said about her husband.

Wendy denied her guilt for years, launching an appeal and a high-profile request for pardon. But they were all knocked back. Even when Brian and Dennis sensationally came out with signed affidavits confessing to framing Wendy for the crime, it still made no difference.

It wasn’t until 1995, almost ten years after the murder, that incredibly Wendy put her own hand up for her part in the crime while still serving time in her prison cell. She said she did it to protect herself and her two children.

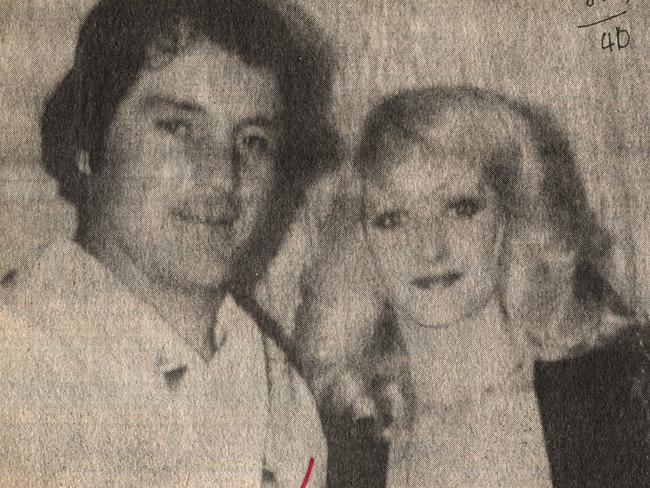

Then, in a magazine article for Social Alternatives, Wendy described how she met Geoff when she was just 15. He was 12 years her senior. He was already married. Had a family of his own. Eventually he would leave them.

“This resulted in the start of his physical and verbal abuse, degradation and intimidation,” Wendy wrote.

It was relentless.

At a pub in Innisfail, she said he “physically dragged me from behind the bar and he beat me until I was unconscious”.

“While I lay there unconscious he proceeded to urinate on me in front of a bar full of men.”

She acknowledged he probably had Post Traumatic Stress Disorder from the Vietnam War.

“He continued to stalk me, rifle in hand as if he were still in Vietnam. He said I was his property; he referred to me as his prisoner.

“He would demand that I lie on the floor with my arms and legs spread out. He would then stalk me like a lion guarding a piece of meat. He would hit me over the head with the butt of the rifle. He would put the muzzle of the rifle in my mouth, cutting it with the foresight and smashing my teeth.”

She alleged these sessions usually ended in her being raped.

“It took me seven years of incarceration for help to be made available to me to understand my actions and the events that took place,” Wendy wrote.

“Worse than a life sentence, the loss of my children who were made wards of state is like a death sentence to me (sic).”

It’s believed Wendy is now estranged from her two boys, despite attempts to mend their relationships.

But there would be somewhat of a happy ending to this otherwise grim tale.

In 1996 Wendy became pregnant to private investigator Robert Dunsdon while on day release at his home. It was four years after they’d met. Robert had seen her in an ABC documentary about domestic violence and had fallen in love.

“She is my soulmate – a woman in a million,” Robert said. “Wendy poses no threat to anyone and it’s a terrible injustice she is still in prison.”

But her incarceration wouldn’t last for too much longer.

In 1999 Wendy was finally released, changing her name to Julia Sage when she moved into a home on Brisbane’s southside with her now-husband Robert and their two children.

While the road to redemption hasn’t exactly been smooth since her release, Wendy is no longer a black widow.

Worse than a life sentence, the loss of my children who were made wards of state is like a death sentence to me.’’

Thousands of Aussies want inquest into Louisa Ioannidis’ death

Calls for an inquest into the death of 24-year-old Louisa Ioannidis, who was found dead in a Melbourne creek, have grown after new evidence was discovered.

‘Silenced and sidelined’: Broken justice system fails victims of crime

Victims of violent crimes and sexual assault say going through Victoria’s “injustice” system was worse than the crime itself, with some questioning whether they would ever report another crime.