ADAM Cooney never feared the needle itself, a small jolt of pain as the silver sheath slipped beneath the surface of his battered knee.

After all, he knew the relief that was to flood over him within minutes of the anaesthetic taking hold.

“Once it settles down you feel you feel like a brand new man. Totally pain free, it’s unbelievable when you get it done,’’ he told the Herald Sun.

But first came the squeamish part, as his doctor poked and prodded with that needle to find his fleshy target.

PAIN GAME: AFL WARNED OVER INJECTION CULTURE

PAIN KILLERS: ‘I WOULD HAVE HAD 250 INJECTIONS’

MAGPIE GREAT: MCGUANE NEARLY DIED AFTER HORROR INJURY

BUDDHA HOCKING: “I WAS GETTING FOUR OR FIVE A GAME”

“It’s hard to explain what it feels like. The needle going in is not too bad. But once they have put the needle in they inject a bit of local anaesthetic, then they move it around so it gets into two or three areas. When they move it around with the needle in there, that’s when it gets a bit hairy.”

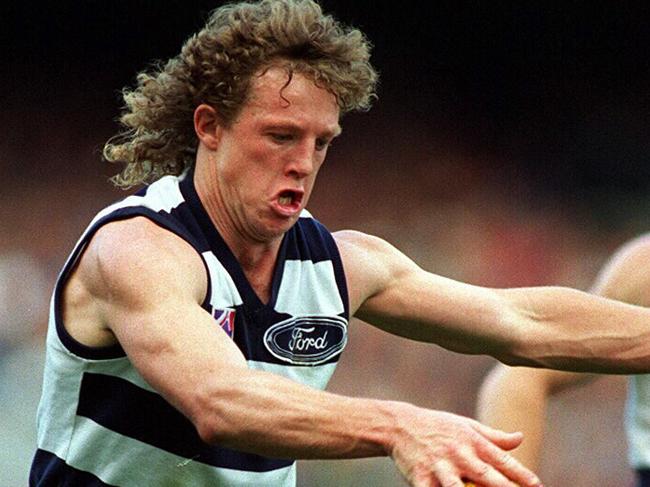

Brownlow Medallist Cooney estimates he needed pain killing injections eight or nine times a season after he fractured his patella and sheared away his cartilage in 2008.

Then it was down to the business of playing football pain-free, before his body’s savage revenge kicked in.

When I used to get it done about halfway through the last quarter it would start to wear off. By the time you come into the rooms and stretch and have a shower, it’s pretty horrendous.

“Obviously you have been running around pain-free and doing all the things your knee doesn’t want you do so by then it’s blown up and you feel like your leg is going to fall off at the end of the game.”

Welcome to the world of AFL football, where players weekly go to extraordinary lengths to play.

A jab to deaden the pain of a broken toe, a shot into the ankle to allow a star midfielder to ignore the pain for one more week.

Football is littered with Grand Final heroic moments from stars who dulled the pain to excel.

From Nigel Lappin’s ribs, to Anthony Stevens’ ankle, to Steve Johnson’s knee, to Easton Wood’s ankle, to Michael Voss’s knee, to Ted Richards’ ankle.

Whatever the cost, it is worth it when a premiership is at stake.

RISKING IT ALL

And yet as Cooney says, the decision to play on when your body is screaming for you to take a rest eventually takes a toll.

When you risk it all for glory, the House sometimes wins.

He cracked that patella during the finals in his Brownlow year of 2008 yet played on in search of that elusive Bulldogs premiership.

He says from that season onward he needed four painkilling tablets — Advil or Panadeine — every time he played or trained.

On game day he needed another two at half time, with anything stronger than Panadeine making him feel nauseous.

“I hurt my knee at 22, so I played nine seasons after that. Add that up over the years, it would have been at least 1500 (pain relief pills).

“I couldn’t tell you how many times I had my knee jabbed or drained. I suppose in hindsight I shouldn’t have played the next couple of weeks with a fractured knee.

“But if the Dogs went on to win the flag and I was on the sidelines ... If you get the reward you live with those aches and pains.

“I have just got to live with the aches and pains and a Brownlow.

He is too much of a joker and laid-back character to mope about the pain but admits he feels so much older than his 31 years of age.

His shoulder is officialy “f***ed”, courtesy of an injection into his AC joint in his first game at Essendon, with the joint degenerating and in need of surgery.

“(The knee) is pretty bad. It takes me a while to get going in the morning. I am like a 50-year-old man. I would hate to see the insides of my guts in 10 years, but you have to put your faith in modern medicine.”

GREY AREA

The AFL has moved on from reckless, anything goes days yet as respected medico Peter Larkins says a grey area still exists.

And yet as respected medico Peter Larkins says, there remains a grey area about exactly when injections should be used on players.

In principle the line is easy to draw — don’t repeatedly inject into joints like ankles and knees, don’t inject if there is a significant risk of worsening the injury.

In practice the lines are a little more blurred.

“There is scrutiny now for doctors and they understand the medico-legal aspect of it. The cowboy behaviour of the 1980s and 1990s is long gone for doctors, I can promise you that,’’ says Larkins.

“I have no problem with it being done in the right circumstances — a bruised rib, an AC joint, a finger dislocation.

But I watched a corked thigh at game recently be injected the other day with a lot of anaesthetic so he could be put back onto the ground.

“He was a hopeless and he was always going to be much worse after that.

“I saw it happen this year with a player who had a bad ankle early in a game and then he missed three weeks.

“There are things like that where a doctor is trying to make a two-minute window of time downstairs as to whether they will jab it up.

“You are totally reliant on the ethics and experience of a doctor. He has to say do I know exactly what the injury is and do I know it won’t be worse next week?

“Forget what the player is asking me to do because my duty is to do what is right as a doctor.”

Larkins says the AFL Doctors Association headed by Hawthorn’s Michael Makdissi now regularly discussed issues like the extent of painkillers used.

“There are extreme variations from some clubs who give only five or six over the course of six months to some clubs who have given 80 or 100.

“By and large there are a crop of doctors out there who are really very good at making these decisions.

“But there are still clubs who have got less experienced guys who are under pressure and they are new on the AFL landscape.

“And those guys are still finding their feet a little with the pressure of match day and the heat of a game with what they should or shouldn’t do to get their players back on the ground.”

FINALS DREAMS?

As Larkins says, the rules effectively go out the window come finals time.

Players are prepared to accept the cost to chase a lifelong dream.

Western Bulldogs doctors performed miracles to ensure their battery of injured players reached the Grand Final, Easton Wood’s badly damaged ankle needing medical assistance.

Steve Johnson kicked four goals on one leg with a badly damaged knee in the 2011 Grand Final, needing injections to pass a fitness test and then play.

Ted Richards needed 12 injections during Grand Final week in 2012 — four of them on the day — to overcome Lance Franklin and torn ankle ligaments that would normally sidelined him for six weeks.

THE STUFF OF NIGHTMARES

Yet there are the horror stories as well.

Fremantle’s Ryan Crowley was banned from football for a year after unwittingly taking banned drug methadone to help with ongoing back pain.

Docker Clem Michael took his club to court after playing for 16 matches of the 2000 season with painkillers, ruining his knee and causing continuing pain.

Adrian Whitehead took seven years to settle a substantial legal battle with Carlton after a club doctor injected his foot in 1997.

He claimed he was not warned of the risks and suffered permanent damage to his foot, as well as anxiety, depression and loss of future earnings.

Experts in the field like the University of Sydney’s David Hunter are adamant players do not understand the long-term risks of painkillers.

The university’s chair of rheumatology — in layman’s terms an expert in arthritis that come from musculoskeletal conditions — is rated the world’s leading expert on osteoarthritis.

The author of 380-peer reviewed studies and a handful of books on the subject, he sees too many athletes who have sacrificed long-term pain for short-term gain.

“As someone who sees a lot of people at a point in their life in their 30s and 40s where they have to live with joint pain for decades I truly wonder whether many of the injections given are advantageous to those people long term,’’ he says.

“Pain is typically a protective response, it’s telling you something is wrong.

“My general advice is maybe a one-off in a joint that is otherwise stable and structurally intact but if you are having repeat injections done every week to get on the field I would strongly advise that is not sensible for a person’s long term health.”

UNDERSTANDING THE RISKS

He wonders if those athletes giving permission for injections truly know the cost — permanent pain, loss of joint function, arthritis, inability to kick a football with their kids

“I wouldn’t advocate it for players so they can run out onto the field even one more time. To me I don’t think it’s worth that.

“You see footballers walking around in their late 30s and early 40s who limp as a consequence of decisions they made in their 20s.

“I wonder if it’s part of the bravado of being out on the field. To express weakness is not often in a sportperson’s dialogue.

“They may say (no regrets) to your face but in between times when they are sitting at home finding it difficult to walk because they are in pain continuously, whether they believe that.”

Hunter says even more concerning is the evidence the injections themselves — using substances like bupivocaine and lidocoaine — actually undermine the integrity of the joint.

“Whether it be local anaesthetic, it can actually do damage to the joint just by injecting the substance itself.”

That research is one reason why clubs like Hawthorn seldom jab players, according to players recently retired from the club.

The AFL’s crackdown in the wake of Essendon’s ASADA fiasco mean all painkillers — injected or used orally — must be logged by player and club.

AFL legal boss Andrew Dillon told the Herald Sun players had to be advised of the risks of pain killing injections.

He is comfortable club doctors manage those risks and make mature decisions.

“We have our controlled treatment list and players have to log everything that they are given, every medication they take or injection they get,’’ he said.

“The individual treatment is done by the doctor and the player has got to consent to it as well.

“There is nothing (problematic) that has been brought to my attention. We are comfortable because the thing we pride ourselves on is the people we have as club doctors and physios are truly professional.

“We back them in and are comfortable with the calibre of people and processes we have got.”

Says the AFL’s general manager of player relations Brett Murphy: “Club doctors have an obligation to help players make informed decisions about their injury management.

“This obligation arises not just from the doctor’s own professional obligations to their patients, but by virtue of the minimum medical standards agreed to by the AFL and the AFL Players’ Association.

“These obligations require that injections may only be administered by doctors, and that they always receive informed consent from the player prior to the injection being administered.”

BACK IN 1989

And yet for every hobbling footballer, there is one like Dermott Brereton.

The real surprise of Brereton’s injury-ravaged injury career is that he played without assistance after his first-bounce collision Mark Yeates in the 1989 Grand Final.

Yet Brereton fiercely defends the use of painkilling injections in football.

As can be expected, he would know.

“I don’t count it like some people when you get an injection into their hip and you inject some and stop and then inject the needle into another spot. Some say that’s six injections but one syringe is one injection.

“I would estimate I have had 250 injections. The club doctor makes an assessment about whether you are capable of continuing on with a painkilling injection.

“And quite frankly was I at risk of further injury from the hundreds of injections? The answer is no.

“It’s not as if my knee is at further risk. I have been bone on bone since 19 years of age. From 1991 when I was 26 to 31, I would have had my knee injected before every game, frequently at half time, and then more often than not I had a big knitting needle-sized needle put into the side of the knee on Monday or Tuesday to have the fluid drained out.

“The doctors who are injecting sportsmen are insanely good. It’s why you trust them with your lives.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Thousands of Aussies want inquest into Louisa Ioannidis’ death

Calls for an inquest into the death of 24-year-old Louisa Ioannidis, who was found dead in a Melbourne creek, have grown after new evidence was discovered.

‘Silenced and sidelined’: Broken justice system fails victims of crime

Victims of violent crimes and sexual assault say going through Victoria’s “injustice” system was worse than the crime itself, with some questioning whether they would ever report another crime.