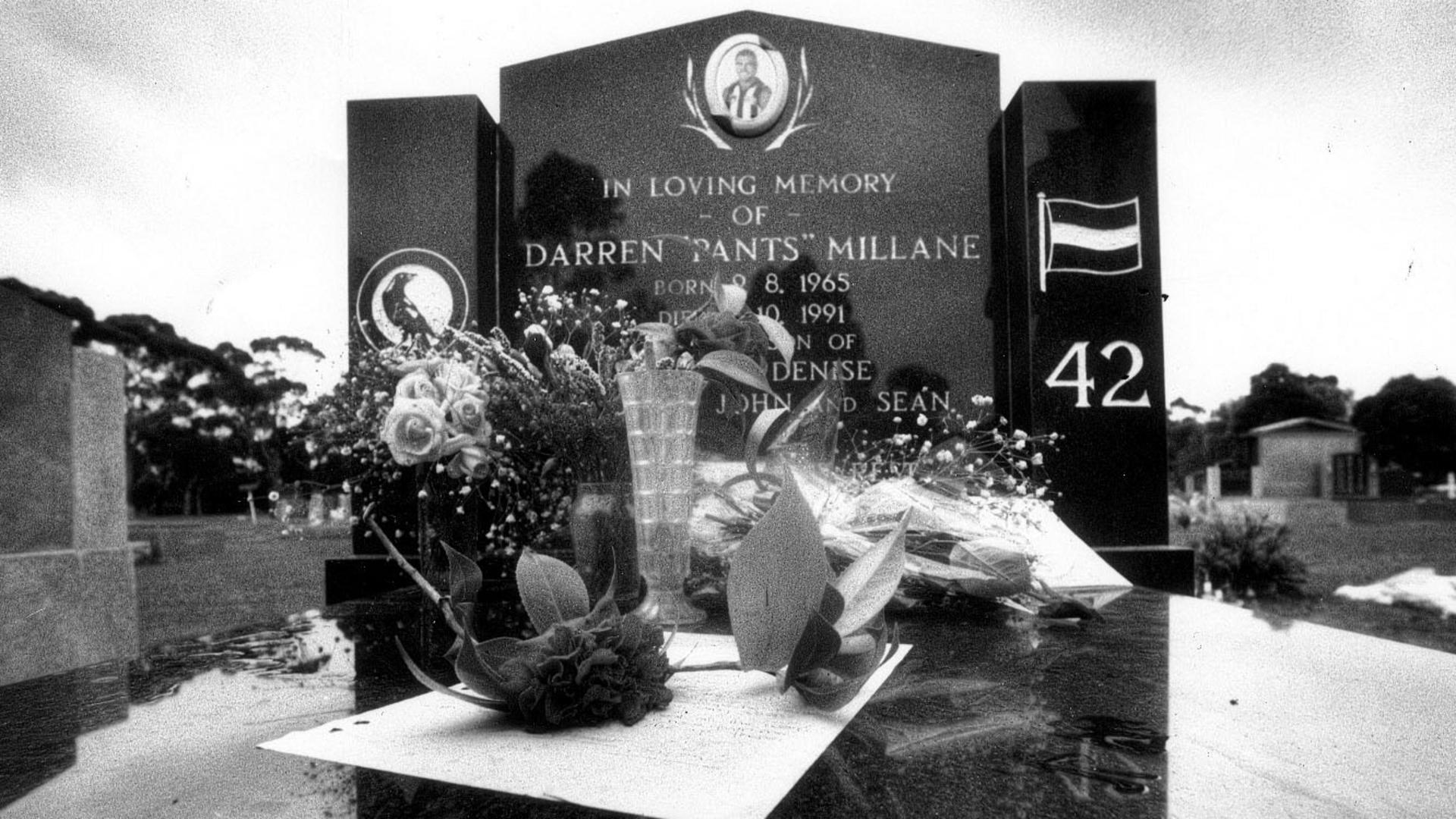

TWENTY-five years ago today the football world was mourning when Collingwood champion Darren Millane died in a car crash. We look back on the story that shocked a state.

GRAEME “Gubby” Allan always kept his phone on. He had to.

Weeks earlier, two of his players had “hijacked” a bus. At the start of the year, another player had flipped a car. Bar-room brawls were routine: so was Collingwood club president Allan McAlister testifying that the accused had a “heart of gold”.

It was a different time, Allan now says.

An era of drink cards and all night booze-ups, followed by AFL football training sessions after an hour’s sleep.

Here, in the spa, talk inevitably switched to the previous night’s conquests, in gossip sessions headed by the wingman who usually headed out, and did it all again, the following night.

As Allan says, his Collingwood steeds were a “bunch of scallywags”.

This particular phone call came after 4am. Allan still replays it in his mind almost 25 years later.

The football manager remembers ringing McAlister afterwards.

One of their players was dead, he repeated. A car accident. He didn’t know who it was. They had to go to the morgue.

They spoke little on the way. McAlister has since recalled the pre-dawn darkness, how the light grew “blacker and blacker” as the destination neared.

A portable phone had been found in the wreck, and only a couple of players owned “a brick”, including the knockabout who was serially summoned to the Collingwood offices.

“I done it again,” he would tell senior officials, as though his infectious grin explained everything.

Both Allan and McAlister clung to denial, a defence dashed when they stood at the glass window.

They asked for the sheet to be lifted higher, to reveal a pair of legs that had pumped, like thick pistons, over four quarters of every game.

Here was the proof they feared – a Magpie tattoo, high on an inner thigh, where only one player had chosen to commemorate the previous year’s flag.

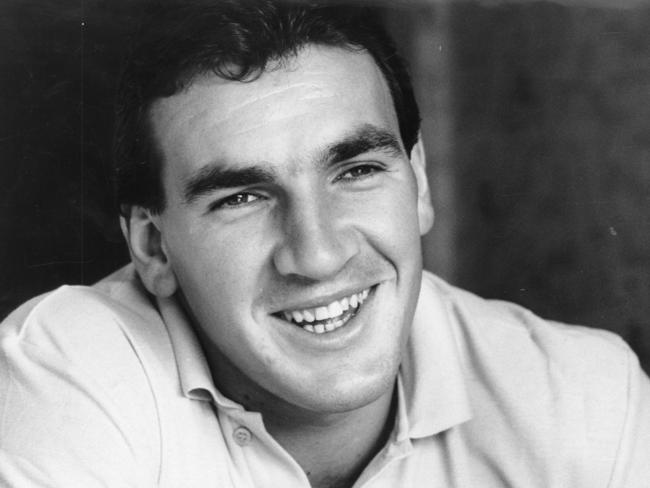

Darren Millane had bragged about his tattoo. He was “Pants”.

Millane once boasted about the “x-rated” origin of his nickname, though his fondness for jeans, stitched with patches of doona cover by his mother, is the better known explanation.

His swagger denoted his disdain for convention.

What’s less known is that Millane was striving to conform to more traditional measures in his final days. At 26, he wanted to grow up.

Now Pants was gone.

Allan got on the phone. He tried Millane’s home in Noble Park. He woke then Collingwood coach Leigh Matthews: “Pants has been killed.”

Someone got hold of Darren Millane’s brother, John, in Queensland. His then girlfriend took the call. She didn’t speak when she disconnected; she didn’t need to.

“It’s Darren, isn’t it?” John asked her. “He’s dead, isn’t he?”

John rang his mother, who lived at the time near Waverley Park. She was heading to work and running late. Her son told her to sit down.

“Mum, he is gone,” John Millane explained.

Denise rang her youngest son, Sean, who did early shifts as a postie. He idolised his brother: at Collingwood, where he had played reserves football, Sean had been called Shorts.

She still regrets her choice of words.

“What’s the matter, Mum?”

“Darren is dead.’’

Sean tried to get his father, Bob, a milkman on his run. Later, Bob Millane was found in his truck, on the side of the road, numbed by the news flash on the radio.

Fellow Collingwood player Mick McGuane was told by his father.

McGuane rushed from Ballarat by cadging a lift from a mate – earlier in the year, McGuane had been done for drink driving.

Player Damian Monkhorst was driving to a plumbing job in North Balwyn. The news report was followed by the hit song of the moment, Wind of Change.

“It’s Darren, isn’t it?” John asked her. “He’s dead, isn’t he?”

Months earlier, Monkhorst had broken bones when he crashed his car. He was “a bit inebriated” at the time.

“You’re a dickhead, you mean too much to the footy club,” Millane had told him.

Michael Christian was sitting at his desk at a stockbroking firm. “No,” was his first response. Pants is “invincible”.

Another team-mate, Shane Morwood, drove to the hospital, to his wife and newborn daughter, whom Millane had promised to take to church each Sunday.

Morwood had broken down on receiving the news. Now he passed people at the local shops and wondered that the world had not stopped.

Farewell the raging bull

THE NOTIFICATION process still upsets the Millanes. Why weren’t they told before the story leaked to the media?

The Millanes were a tight bunch – they still are – even though Bob and Denise had separated in 1990.

They cocooned themselves in Noble Park, to mourn the man Darren would never become. The public, meanwhile, championed the sportsman he had been.

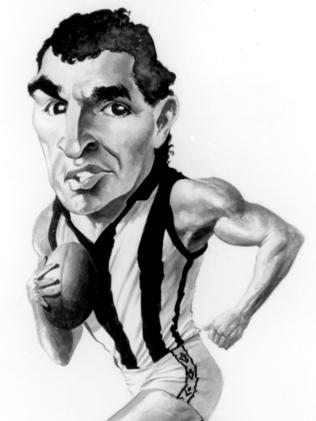

The soft touch and the “Raging Bull”, as the fan tributes read, resided together behind the footballing veneer.

Millane defied the easy assumptions.

If he was a brute and a prankster, he was also a thinker and cheerleader. The divide between the private and public personas struck Matthews at the time.

His players, Millane’s closest friends among them, would mourn the loss of both.

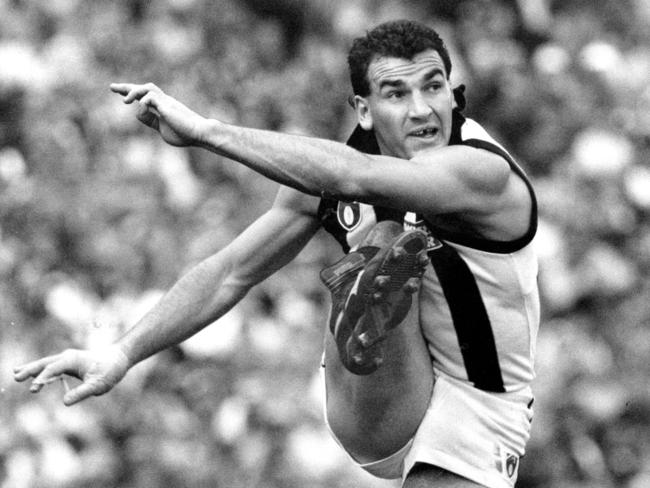

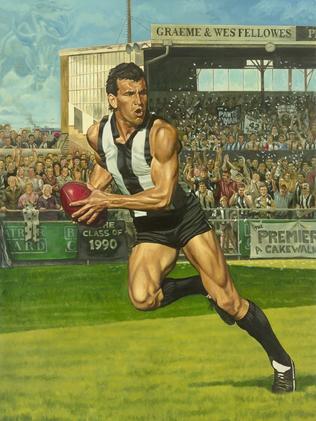

The year before, Millane’s broken thumb, wrapped in a tattered bandage, clawed Collingwood’s first premiership cup in 32 years.

As a lesson in hope, the timing had been sublime. Victoria had slumped as the rust bucket state. Uni graduates stacked supermarket shelves, grateful for the work.

Victorians felt cheated by their political leaders - they would be warned to brace for the “worst” ever Christmas.

The unlikely Collingwood flag had been inspired in large part by a footballer described by his coach as “sort of nonchalant, almost blasé”.

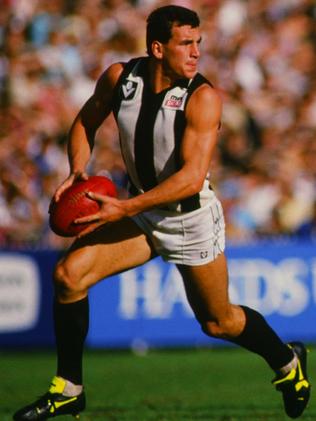

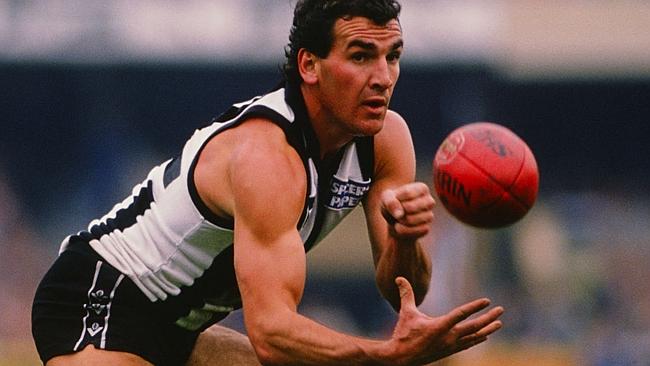

Millane blended on-field hardness with off-field showmanship.

He invited confrontation and he demanded attention, all flair and little give, as though full throttle was the only measure.

Here was a footballer, says team-mate Doug Barwick, who “epitomised the era”.

Then, one October morning, full throttle exploded in a shriek of metal in an Albert Park street. No one was prepared for this – Millane himself had pledged to change in the weeks beforehand. His death would unofficially mark football’s farewell of larrikins and their tribes. Then AFL chief executive Ross Oakley calls it a “turning point” in player welfare.

In the four years to 1995, AFL player salaries would rise 75 per cent. The game would be reinvented as an industry, and the thuggery would be taken off-field, to the boardrooms, where the assaults would be committed with calculators.

Millane’s death would unofficially mark football’s farewell of larrikins

Counselling sessions would come to replace cover-ups. It seems that Millane’s excesses would have been retired no matter what.

Those players who followed his lead, from Brendan Fevola to Wayne Carey, would not be coddled in the new straitjackets of societal reform.

“You couldn’t get away with that now,” says Millane’s then team-mate, Craig Kelly, of the binge drinking culture.

Yet Millane wasn’t getting away with anything. Not at the time. He was disappointed only when those around him didn’t join in.

When Kelly slipped away from drinking sessions, he feared what Millane would say the next day.

Millane would have a “massive skinful the night before”, then roll up to training.

If he reeked of ouzo, as another team-mate reports, he seemed inured to a hangover by his “enormous constitution”.

He led the Collingwood boys’ club, which delighted in asking the female dietician to inspect their “skin folds”.

For the spa sessions, Millane often heightened expectations by pinning an item of clothing on the noticeboard beforehand.

Allan, the players’ disciplinarian, looked forward to Monday coffees, when Millane would spill his weekend activities.

Then Collingwood club surgeon John Bartlett recalls being regaled at Thursday night sessions in tales that still get re-told, year after year, at regular dinners of past players.

But the medico credits “the magic of his personality” to something else: “Darren wasn’t one of those celebrities who’d be looking over your shoulder to see if there was someone more interesting or more important to talk to. What I loved about him was that if you were talking to him you had his complete attention.”

This “presence” – or “charisma” - was not a public commodity on the day that Millane died. It was unfamiliar to the young women who wept for the tv cameras.

Millane had refused to speak to the media for chunks of his latter career, citing a negative tone that his family still thinks unfairly cast him as a thug.

The default grin of the club’s “spiritual protector” was reserved for his mates. The public also saw the blank stare of his walks to and from the court-room.

It didn’t matter. Millane’s car accident sounded avoidable, but his memory was not about to be shackled to blame.

He counted, in part because he seemed so proudly misplaced. He pulled it off, whether he was playing football with broken bones or mangling a Sinead O’Connor ballad on stage.

Millane threw back to class divides, when humble origins doubled as a battle cry.

He was a pillar in uncertain times and also a rebel - only beginning to embrace the scale of his cause.

HIS was to be a loss without modern precedent.

The idea that Millane had died as he had lived - by overstepping the accepted norms - compounded the jolt.

The grief, like his take on life, flowed without a rule book.

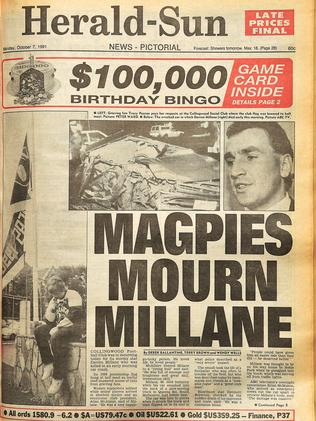

The public tallied a record 1200 tributes in the Herald Sun. Prime Minister Bob Hawke expressed his written sympathy to the Millanes.

Millane’s defence lawyer wrote to them that he did not normally befriend clients. Yet he would “be very proud” if his little boy “grows up to be as decent” as Darren.

The notes lie crammed in boxes now, along with the photos of kids Millane visited in hospital. A woman he had dated wrote to the Millanes about their “gentleman” son. The parents of Peter Crimmins, the Hawthorn captain who died of cancer, aged 28, in 1976, offered support.

Now was hard, they said. The years ahead would be harder.

The surviving Millane brothers took the phone off the hook in those first few days.

They viewed the body to ensure it was “presentable” for their mother.

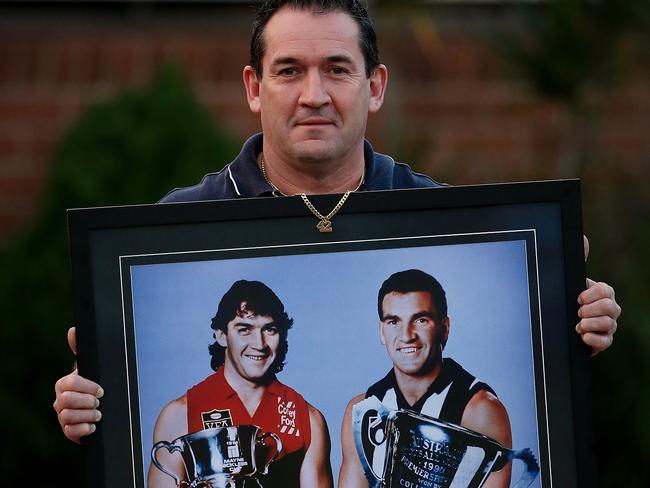

They were consoled by some of Millane’s closest friends, such as team-mates McGuane and Denis Banks.

McGuane remembers throwing one another into the backyard pool to lighten the mood. Something like 50 slabs of beer were downed at Millane’s home in those first 10 days after the death, a response which Sean Millane now likens to an anaesthetic.

His pain welled later, when he moved into Darren’s converted garage, where a James Dean poster hung on the wall.

There, Sean played over and over the recording of his brother’s funeral and unfairly blamed himself for his brother’s death.

Denise, who would take to sleeping with a photo under her pillow, recalls the funeral director explaining the need for a bigger venue.

“They said the crowd would be too big,” she says. “That hadn’t dawned on me. It stunned me.”

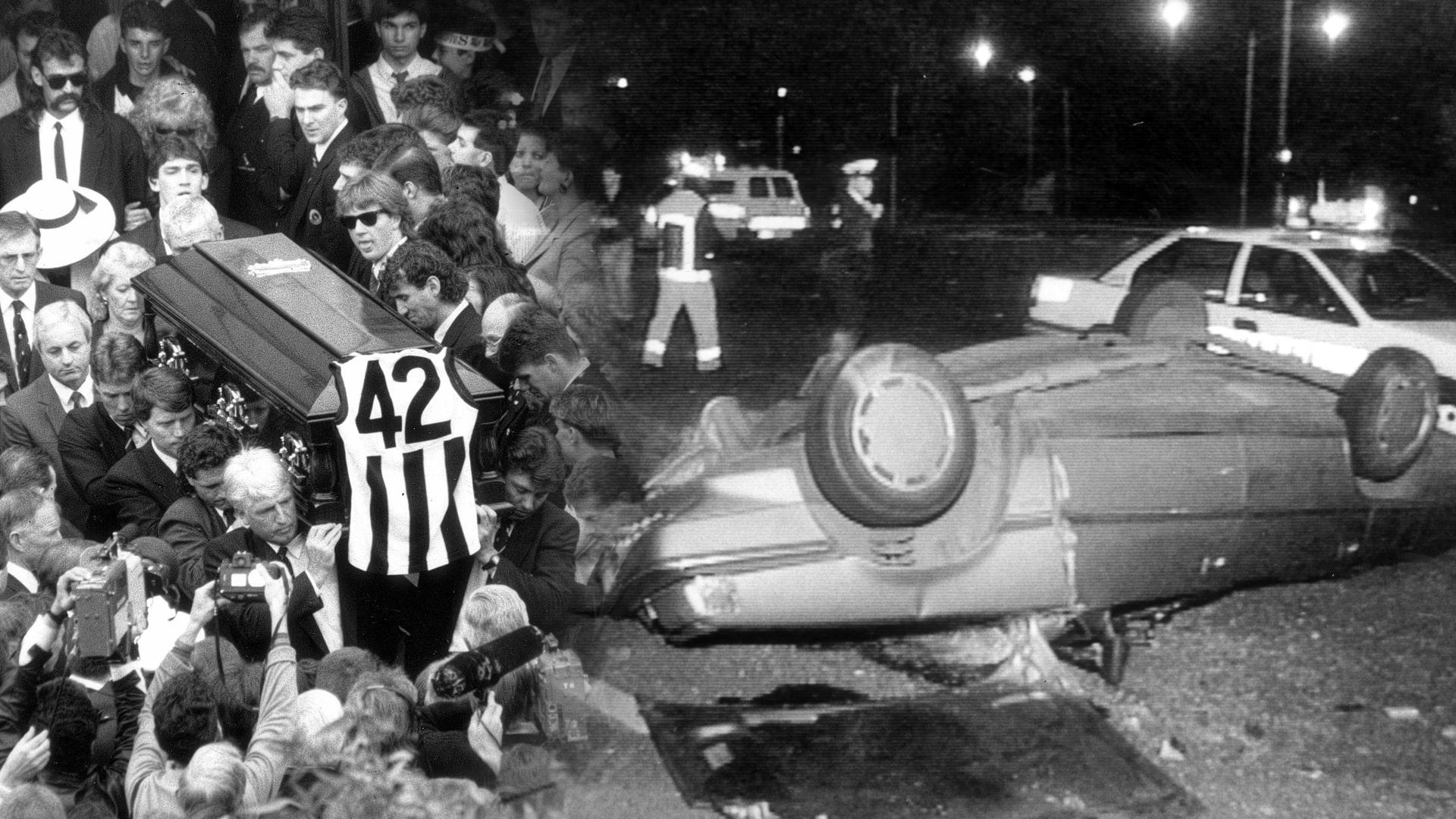

The 7.30 Report spoke of a turnout at Dandenong Town Hall that may puzzle “people who don’t love Australian Rules football”. Many of the 5000 or more mourners reached for the hearse as it left for a gravesite that would be flushed with flowers for the next quarter of a century.

Millane’s death didn’t make sense then; perhaps it still doesn’t. He was too young, too animated.

The son who joked with his mother that he would never get old was doomed to “always be 26”. As team-mate Craig Kelly said in the days after the accident, Millane had only one pose: “I’m here. You have to go around me.”

Inside the hearse, John Millane hoped that the service had been as his brother would have liked - “not this sobby, crying griefy sort of thing”.

Splutters of laughter are how he remembers what black-and-white photos depict as grim and forbidding.

Sean told the audience about the best man he could never have.

John cannot recite the exact words. His family was gazing out at a crowd 500 metres long and ten deep.

He thinks his father Bob said something like: “If you want to go out, you want to go out like this.”

“It was like everything he did in life was huge,” John now says. “This was no different.”

‘You can’t do that’

MILLANE’S team-mates had gathered at his home a week before his death. They chatted about the 1991 season and plotted a better 1992.

Here was the old and new Millane in a closing snapshot. A future captain, rousing his team with his most reliable props - beer and singing contests.

Millane was fresh from sessions with Ray Giles, the boxing trainer famed for his torturous sessions, and a Gold Coast getaway with mate Denis Banks.

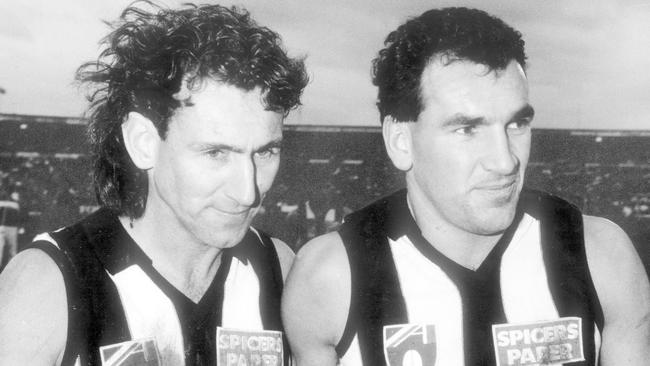

The pair had first bonded in 1984 over a friendly argument about their respective origins (Banks was from Reservoir). An on-field chemistry translated into their nightclub adventures.

They looked out for one another when overindulgence, or a rowdy patron, slowed their fun.

Millane was learning to turn away from battles, Banks says.

“Every year he changed,” he says. “I was out with him all the time, saying ‘you can’t do that, mate, you’ll get yourself into trouble’.”

By 1991, two bar fights – one involving father Bob - had landed Millane in court.

In one case, in which the victim claimed a broken nose, the magistrate said he was tempted to jail Millane; in the other (stitches, bruises), imprisonment was “certainly an option”.

Yet the excesses are explained away – by those closest to him - as the wrong choices for the right reasons.

Footscray star Doug Hawkins wrote to the Millanes after Darren’s death.

He had a “strange brotherly relationship” with Millane, who “stood guard” over loved ones. “We attacked and took chances and sometimes got caught…” he wrote.

Another outstanding court case involved Banks. On the morning after Collingwood lost to Geelong in 1991 and lost a chance of playing finals, the pair boarded a parked bus at Spencer St station. They’d been out clubbing all night.

Banks reversed the bus a metre or so. When the driver objected, Banks punched him down the stairs.

“Pants didn’t do anything,” he says. “One of the guys, maybe the driver had a crack and Pants was just sticking up for me.”

Banks would plead guilty and receive a good behavior bond when the case reached court after Millane’s death.

Its consequences for Millane were far more reaching.

Ashamed of the publicity, he had offered to resign from the club.

The club refused – by then, as Kelly puts it, it had “really started to knock the rough edges” off the wayward wingman.

Privately, Millane feared a conviction – compounded by the earlier assaults - would put him in jail. His reverie was apparent to his dearest.

Brother John speaks of a “plan”. Another confidante identifies the bus incident – and the blaze of publicity – as the trigger, the beginning of the end five weeks later. The intense training program and the blowout, one extreme to the next.

He was a natural leader, says Kelly. Matthews says he was “incredibly influential” and “undoubtedly” loomed as a future captain.

Future scenarios swirled in Millane’s mind when he drove back from that Geelong game on August 31 with then Channel 10 reporter, Eddie McGuire.

Millane needed to talk: he knocked back McGuire’s offer to stop for “travellers”.

Millane had been restricted to small contracts, largely because of his wayward exploits. He hoped for extra responsibility and rewards, but his aspiration ran deeper.

Millane had glimpsed the other side: there was more than dingy bars and ouzo shots. He yearned to shed the more undesirable elements of who he had been.

“He was really making the connection between being a suburban footballer from Noble Park and finding the next stage in his life,” McGuire says.

Shane Morwood, one of his closest friends, had watched a “lad from Noble Park” become “the full package”.

John Millane says his brother had grasped an essential tenet – perceptions mattered.

McGuire speaks of himself, Craig Kelly, and stockbroker Michael Christian in the same breath. “We were all thinking big,” McGuire says.

“We didn’t know where we were going, but we were all on our way. And he was ahead of all of us.”

If so, Millane had come a long way.

Denise Millane recalls a “little villain” in nappies who ran away from home.

In the schoolyard, Millane once threw a boy into a window. It sounds bad, she agrees, except that Milllane had stepped in after the boy split a girl’s lip.

He had never cared what the world thought, a lifelong strength that had only recently doubled as a weakness.

Morwood says that Millane “didn’t want people to know about” his dedication to the needy. Daicos discovered after Millane’s death that the footy gear Millane pestered him to sign was being delivered to the Royal Children’s Hospital.

He lived with his mother and grandmother.

Mum did his ironing: she received invitations to functions, along with his girl of the moment. His day job at a cleaning company was a mundane necessity in an age before soaring salaries.

Millane’s refusal to take a “backward step”, as Shaw puts it, sits nicely with the great grandfather who, as the story goes, survived the Titanic sinking after hitting the whisky.

Millane is also linked to Eureka Stockade leader, Peter Lalor: if the lineage sounds patchy, a shared disregard for authority is not.

He was the young talent who was unfazed when told on refusing a Sydney offer: “If you won’t play for us, you won’t play for any side”.

He walked away from a Hawthorn pre-season because the players were “a bunch of arrogant pricks”.

At Collingwood, the players introduced themselves.

He was playing seniors after two reserves games, kicked the VFL’s goal of the week two weeks’ later, then starred in a losing final game against Essendon.

Shaw still remembers the first time he saw Millane.

“He came in the gym and he had these tracksuit pants on with a gold gymnasium shirt,” he says. “I thought, ‘Sh-t, this bloke would want to be good’. He would want to be able to fight and play. Fortunately he could do both.”

Yet the knockabout had lifted his sights. McGuire says that Millane was gravitating to better haunts and cliques, much to coach Matthews‘ relief.

McGuire believed Millane’s “time was coming“.

The future Collingwood president was on-air early at Triple M early on October 7, 1991, when the police asked media outlets not to release the name of the “celebrity“ killed in a car accident. “I‘ve got a feeling I’m going to find out that one of my mates is dead,“ McGuire joked with a colleague.

The dead driver’s identity, the mate determined to stop “mucking up“, still rocks him.

“Two years earlier he would have been 6-4 on favourite,“ McGuire says. “But he was the last person I thought of at that stage because of his mindset.”

Thumbs up

MILLANE‘S illusion of invincibility still thrives today.

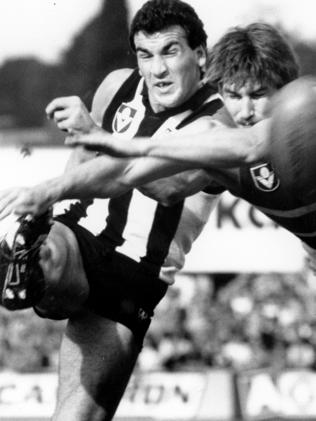

Last year, a Facebook thread was debating his 1990 bump of Michael Werner.

The Essendon player launched himself at Millane, who tucked a shoulder for impact. Werner bounced off Millane like a cartoon character hitting a wall.

MILLANE IN HIS OWN WORDS - READ HIS MEMOIR NOTES IN FULL

Morwood recalls two Richmond players once stepping out of Millane’s path.

Millane didn’t snipe, he hulked.

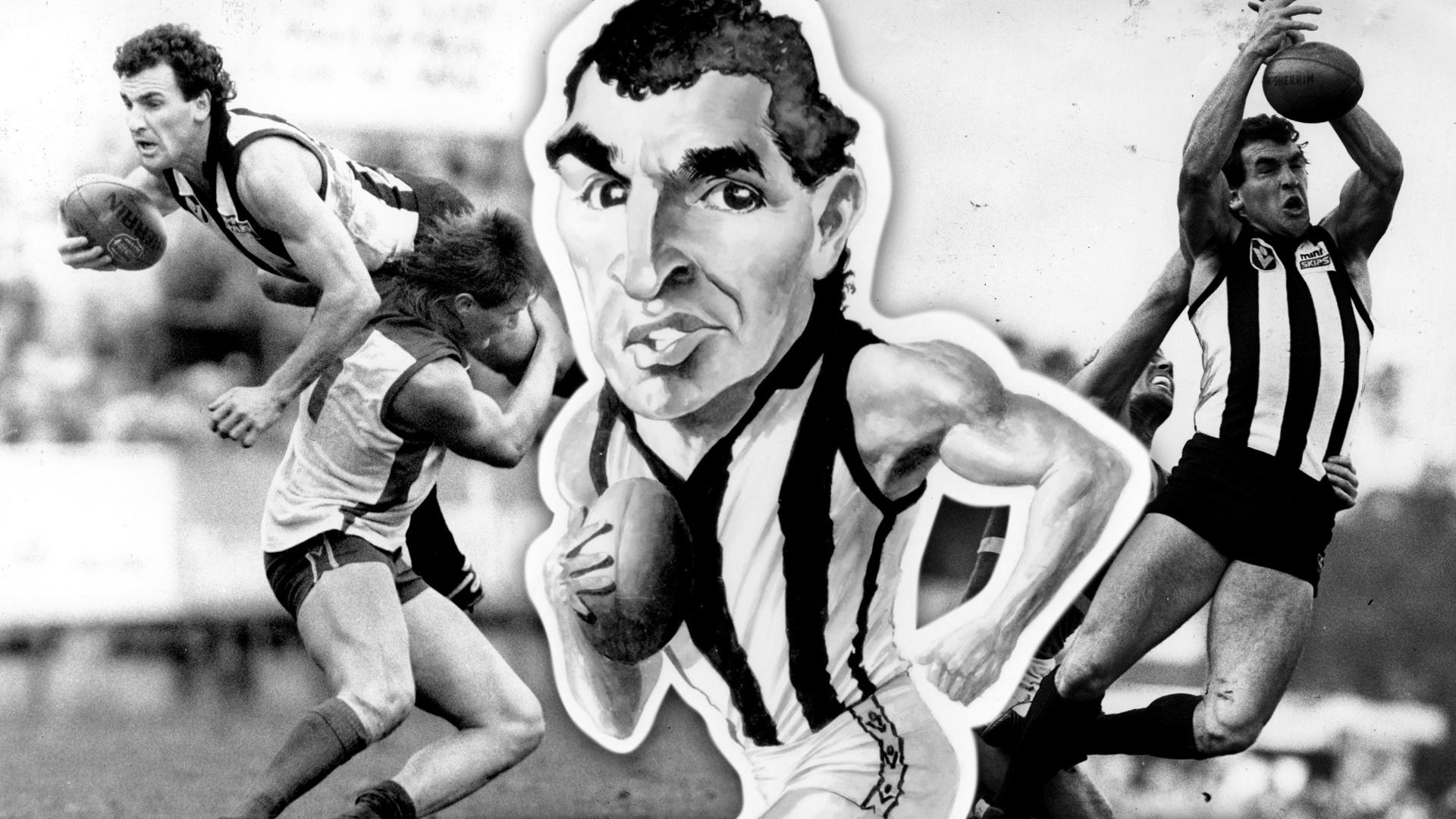

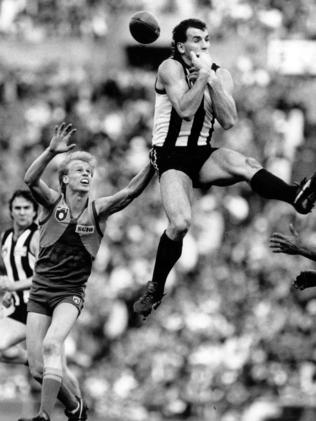

His ferocity at the ball overcame a slightly awkward kicking style. Yet his impact was more than physical: Millane’s instinct for on-field emotions lent him an aura.

Peter Daicos, the goal-kicking freak of video replay immortality, looked to Millane at the start of every game for motivation. Daicos was the team’s pin-up, Millane was the pulse.

Opposition teams knew that Millane was Collingwood’s conduit out of defence. Yet Daicos says they mostly shrivelled in his shows of strength, cowed by the same shows of “prancing” and “intimidation” that lifted his Collingwood team-mates.

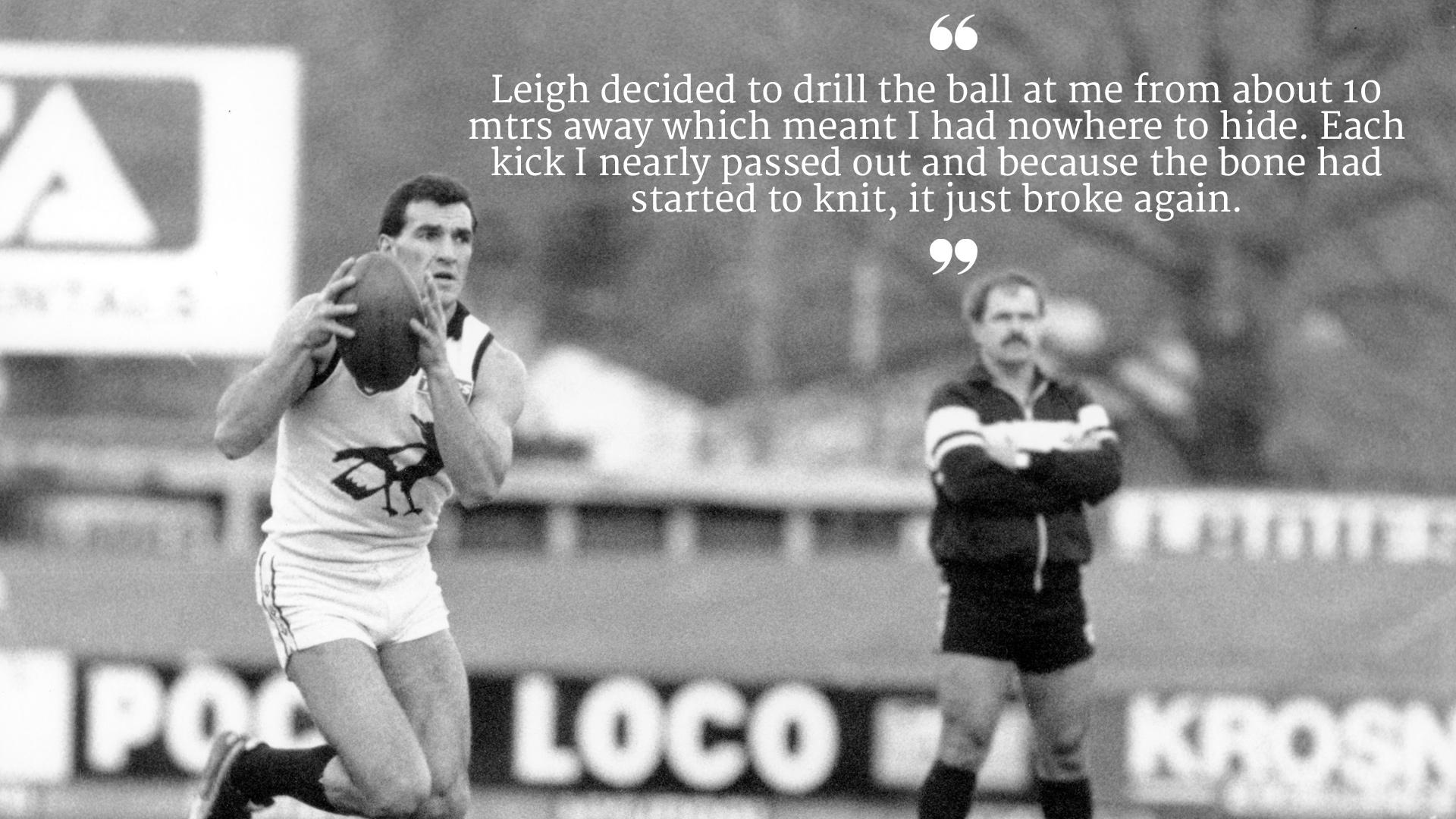

Millane’s ability to adapt and thrive is one of football’s better tales.

He fronted with a shattered thumb for each game of the 1990 final series. He should never have played. He knew it. Dr John Bartlett knew it, too.

In the second last game of the regular season, Millane cracked the base of his right thumb so badly that it was displaced from its saddle-like groove on the wrist.

The only solution to a Bennett’s Fracture is immediate surgery and eight weeks off. Bartlett says the pain is beyond the “ordinary mortal”.

The coach and surgeon wrote off Millane, who then insisted otherwise.

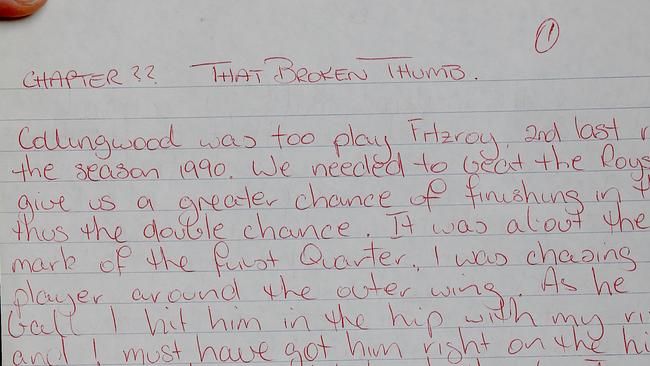

He wrote down his fears at the time.

Sean Millane found the thoughts in a box while moving house more than two decades after his brother’s death.

It seems that Millane was toying with a book. Four pages in all, in neat cursive script, headed:

“Chapter ?? THAT BROKEN THUMB”.

Millane “nearly went through the roof” when Bartlett strapped the thumb on the Friday after the break. He then tried to “put one over” Matthews.

In the coach’s office, he tossed a ball up and down. He told Matthews that Bartlett had said the thumb would be ok, with painkillers.

Just as Millane felt he had convinced Matthews, the descending ball hit Millane’s thumb, and he dropped it.

“Why don’t we just have a little kick…” Matthews decided.

Matthews fired a dozen to 15 lightning passes at his player.

“I had nowhere to hide,” Millane wrote. “Each kick I nearly passed out and because the bone had started to knit, it just broke again.”

Millane somehow convinced the selectors, then went home and vomited from the pain.

He almost rang Matthews to pull out – if he had, he would have missed the 1990 finals series. Instead, he endured the night to see how the thumb felt in the morning. It was ok, to his surprise.

He turned up for the North Melbourne match, the last home and away game of the season, and had painkilling injections, the first shot so painful he needed water to avoid being sick for the second and third. When he warmed up, he broke the thumb again. He had 30 touches that day.

He would repeat this process again and again for the next five weeks. The thumb would break anew with his first grab of each match.

In tears, Millane would avoid contact in the rooms afterwards, for fear of knocking the hand.

Matthews credits Millane for adjusting his game.

“Even with the half use of the hand I thought what his body gave us was as much as what he would have with a good hand because he was able to play within the limitation,” he says.

When Millane threw the ball aloft on the 1990 grand final siren, his grin doubled as an emblem of struggle after Collingwood’s epoch of failure.

He had had 28 possessions, more than any other team-mate except Shaw.

“I don’t think so,” he told the umpire who asked for the ball back.

He made a bad decision and paid the ultimate price

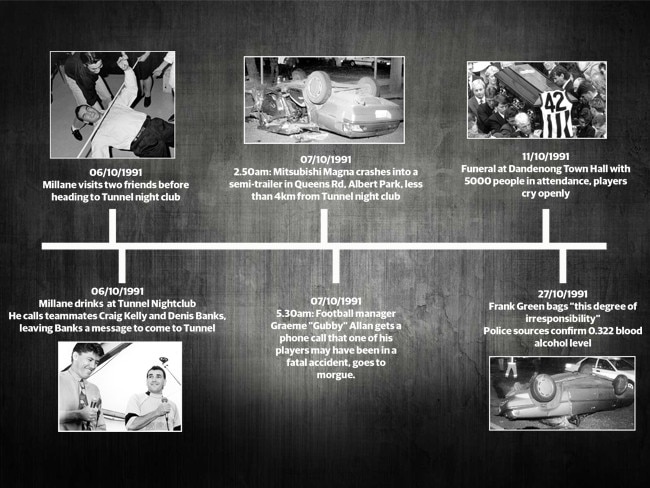

SEAN Millane was supposed to be at Tunnel nightclub on the night of October 6, 1991. Darren was not: he had planned to be 200km away, in Benalla, after a Saturday night wedding in Cobram.

His party weekend had gone as expected, if previous habits are a measure.

Millane was up until 4.30am on Sunday morning, singing along to TV music videos with two women in a hotel room.

He was awake four hours later: sinking beers two hours after that.

He signed autographs at a country footy club. Then, an unplanned choice, the first of several - a return to Melbourne.

Naturally, Millane sang badly for the ride home.

At 9pm, he arrived at a North Melbourne pub, at 11pm at another regular haunt, the Tunnel. He had his own corner at the Little Bourke St nightclub, where a plaque would be posthumously hung.

Tunnel was a throbbing clot of denim. Patrons bopped past dawn, fuelled by drink cards and the promise of footy player sightings.

Millane hosted his own “fan club” here: he was always circled by hopeful women.

“Most of the players in Melbourne came to the venue from time to time,” says owner Peter Iwaniuk. “Darren was like part of the family.”

Friends and acquaintances lined up to testify that Millane did not appear drunk on his final visit. Another witness knew Millane very well. She told the coroner that Millane was very drunk, and she was right – his blood alcohol content was later measured at 0.322.

She was surprised that he had been able to get in a car by himself.

Banks and Millane looked out for each other, both on and off the field.

Their mates system wasn’t foolproof, as the bus incident had shown, but they trusted in it. The problem this night was that Banks wasn’t there. Nor was Millane’s kid brother.

Sean had opted against going after a dust-up with a mate over a girl. He boasts many hairy tales, such as the time he fell six storeys in the Hilton Hotel’s laundry chute. Yet boundaries contained the antics.

Millane would sometimes drink and drive, Sean says, but not when he was around.

“I blamed myself for a long time,” he says. “Had I been there he probably would have got a cab home.”

Millane may have tried to get a cab, as he often did. Iwaniuk, for one, says that his staff would not have knowingly allowed their VIP guest to drive.

Denise Millane says she often drove her son to collect his car after a big night.

Millane may have got a cab from Tunnel on the night he died - to get his car from nearby.

This is John Millane’s recollection. That the car Millane crashed was not his, but a car on loan while he awaited delivery of a new car.

Sean Millane recalls a car yard later demanding payment for the wrecked vehicle.

Perhaps Darren lacked money for the taxi home. Perhaps he fretted about getting the borrowed car home, which a friend recalls had been parked in town over the weekend.

John Millane can only speculate about his brother’s choices.

The Mitsubishi Magna hit, at speed, the back of a slow-moving truck in Queens Rd, Albert Park. The truck driver heard a “thud”. Millane’s vehicle resembled a crumpled Meccano set.

Denis Banks got the phone call from Allan about 5.45am. He had gone to bed with Millane’s rendition of Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road in his head.

He had gotten home to an answering machine message that Sunday night. “Get down here,” Millane had said, calling from Tunnel. “You’re weak as piss”.

Millane often slept at team-mate Craig Kelly’s place.

Millane had his own room there, to avoid the sort of journey he was now thought to have undertaken.

Banks tore over to Kelly’s Abbotsford home from his Fitzroy address. Banks jemmied a door and set off an alarm.

“I went in there hoping to find him in bed,” he says. “He wasn’t there when I looked in, and it was hitting home that the story was right.”

Banks’ sadness receded into emptiness in coming years. He had lost his best mate to a “big risk”, at a time he had been “maturing and learning to become a better person”.

I went in there hoping to find him in bed

Banks works too hard, and his spare time goes into his kids. He loves his new life, but the “massive void” endures today.

“If there was trouble, he was starting to walk away from it, to get away from it,” Banks says. “I know that contradicts him getting pissed that night, but he made a bad decision and paid the ultimate price.”

James Manson, the ruckman who debated Cat Stevens lyrics with Millane, says he resembled a “character from Caddy”. Yet the loud pants hid “an awareness”, or what Banks calls a “soft heart”.

Manson once told Millane that he could not imagine him getting old.

“You know what, Jimmy,” Millane replied. “When I am older, mate, I will be on the Gold Coast, sitting on a beach, with my suntan, my big gut, and my medallion around my neck.”

Darren’s death not the only loss the Millanes faced

SEAN MILLANE is wide across the chest and tells a good yarn. Once, after a haircut, his mother had to catch her breath at the resemblance to his lost brother.

Darren skipped into the big league whereas Sean would settle on a fine footballing career in the VFA and VFL.

Sean is a father who has confronted loss again and again. That’s the difference, of course. He hobbles on wobbly knees, but he’s still here.

He and mum Denise do their best to keep Darren around.

Their most tender memory took place in the most public of places.

After the 1990 grand final siren, John, Sean and Denise rushed to the MCG fence. Sean didn’t know how his brother heard through the din of almost 100,000 people, but Darren rushed over and the family embraced.

“Meet you later on,” Millane said. “We’ll get on it.”

Former Fitzroy player Jamie Cooper turned to art after football. His painting of Millane on the Victoria Park wing swallows visitors at the front door of Denise Millane’s Noble Park home.

Her house is cluttered with footballing glitters: somewhere, she’s got the pins from Darren’s thumb surgery after the 1990 grand final.

The number 42 jumps out at the Millanes on street signs and in restaurants.

Sean likes to recount the coincidences. For his 147th VFA game, Darren’s AFL career total, Sean threw down his bag at a Victoria Park locker - his brother’s.

An ex-girlfriend of Millane’s has three ornamental ducks on a hall table.

They move without explanation, and she ”knows” it is Darren.

The supernatural is a recurring thread in the Millane remembrance. Five months before Millane’s death, Denise Millane visited a clairvoyant.

“She said to me: “One of your boys is going to have trouble with a car. He is going to be in the wrong place at the wrong time”.

After the funeral, she remembered the conversation. “I thought to myself, this isn’t fair, why didn’t she tell me more, I could have stopped it,” she says.

I have no doubt we would have won in 1992 with him

SEAN Millane got another phone call many years after the first.

“We’re not 100 per cent sure but we think it’s your father,” the police officer said.

Bob Millane had left a note. He was a “lost soul for many years” and beyond the reach of the youngest son who rushed to help whenever his father threatened the worst.

Sean Millane’s proximity to grief has qualified him for unexpected roles.

He has become a “go-to” for others, as has his mother.

“People say: ‘How do you get over it?’”

“Well you don’t, you just learn to live with it... I’m not going to see my brother again. I’m not going to see my father again. I’ve learned that the world turns. It’s not going to stop for me. At times you’d like it to but it doesn’t.”

Instead, Sean Millane recalls happier moments, such as fish and chips in the back of his father’s truck after schoolboy football trainings.

Denise remembers the little loss that hurt deepest – her and Darren’s Saturday morning tradition of washing each other’s cars.

Last year, for Darren’s 50th birthday, a Brighton restaurant lunch included surgeon John Bartlett and some of Darren’s school friends.

Bartlett spoke about Millane’s thumb, Denise explained why she’d given the 1990 grand final ball to Collingwood to display.

The merriment hid the everyday ache of what-if.

McGuire “knows” that Millane would have been an “absolute star” on The Footy Show.

John Millane identifies in his brother the analytical mind of today’s coaches.

“I think he also would have been smart enough to be that Billy Brownless type of personality that everyone loves,” he says.

Craig Kelly, now a prominent football manager, says his friend had charisma and drew an audience: more importantly, he was growing up.

”He probably would have settled down, got married and had kids,” Kelly says.

Other possibilities still go unanswered.

McGuane upped the training schedule he’d embarked upon with Millane after the 1991 season. Over the following year, he went out with the boys until late, but only sipped water. He won the club’s best and fairest award in 1992 and 1993.

Had Collingwood lost more than a revered player? Millane’s friends and family believe that AFL finals history was probably changed by his death.

“Absolutely, it might have been different,” Matthews now says of Collingwood’s finals’ elimination in 1992.

“We would have smashed it,” says Daicos of the 1992 finals campaign, echoing a lament of many of the 1990 flag-winning players.

“I have no doubt we would have won it with him.”

The AFL’s Ross Oakley calls Millane’s death a “wake-up call”. Clubs are now held responsible for their players, a small but enduring positive from a tragedy.

“All young fellows have moments in their lives, they all have that bit of a scallywag in them, particularly sportsmen who are required to be strict in their training regimes and so forth, and they sometimes break out,” he says. “It still happens today, unfortunately.”

The Millane’s fixation with the number 42 seems like a lifelong sentence.

Yet there is one place, the Collingwood jumper, where the question of sightings gets muddled.

The number was retired from the Collingwood list after Millane’s death.

The club aired plans to bring back the number, but its approach at the time upset Denise Millane.

The family would like to see a round each year when Collingwood players wear a small 42 on the jumpers, perhaps above their hearts.

As for the official number itself, Denise is clear. She is a grandmother to three, soon to be four, including a little boy nicknamed Jocks.

Why not wait until the next Millane plays for the Magpies?

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

How tragic end of two young lives ripped Echuca families apart

Two well-known drag racing families were torn apart by “a few seconds of thrill” that has left them with a “lifetime of pain”. Read their harrowing words about the impact of the deadly crash.

Long way to the top: The journey of the world’s greatest rock band

The world’s biggest rock band AC/DC packed out regional halls and suburban pubs across Victoria for $3 per ticket before they ever dreamt of selling out stadiums. These lucky fans were front and centre.