Richmond finals: Can the Tiger army finally dare to dream?

THEY haven’t seen a flag since the Commodore 64 hit the market. Fans have suffered, microwaved memberships, and adapted. Are Richmond fans finally to be rewarded? Patrick Carlyon asks them.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE tale goes that Richmond Football Club stands to gain a prized piece of local real estate. All the club must do is what fans long hoped that it could — and long despaired when it did not.

A homeowner — and loyal supporter — has not told his family of his promise. Perhaps he should — soon. If Richmond wins a flag, the owner has said he will donate a property — once the home of the club’s spiritual icon Jack Dyer, no less — to the club in thanks.

This joining of once mutually exclusive elements — Richmond and a Grand Final — is the novelty football story of 2017. It may not come to be, but it could.

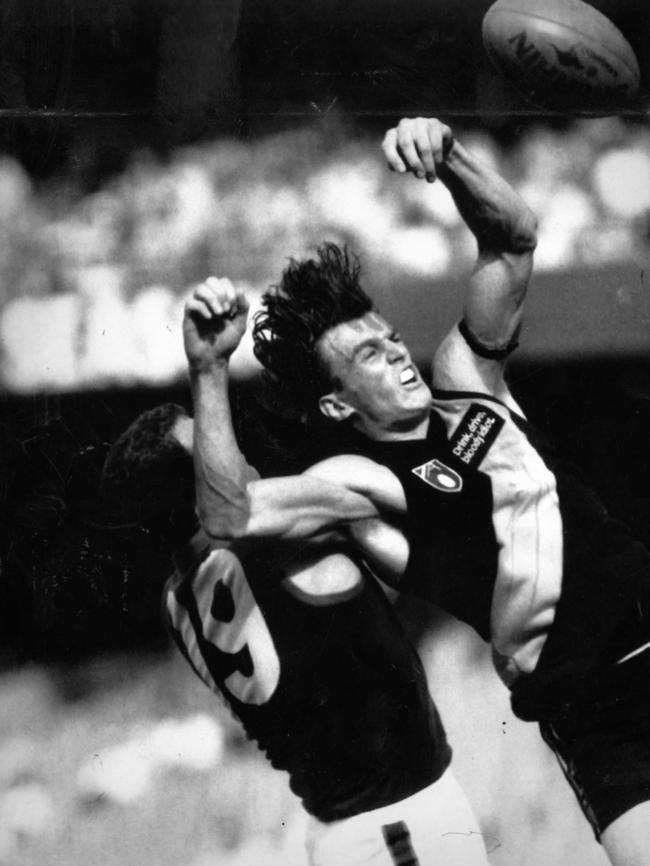

A win against St Kilda on Sunday puts Richmond in the top four.

Fans face the usual ifs and buts of the finals lottery, as well as the default doubt that cloaks the modern Richmond supporter. Yet the team would command a finals double chance, and inherit the fairy dust sprinkled by the Western Bulldogs last year.

The notion of a Richmond flag pairing — dormant since the release of the Commodore 64 computer — has jogged a sleeping army of depressives and malcontents.

Sound judges — and sentimental hearts — think they can belong together.

MICK MALTHOUSE: RICHMOND PREMIERSHIP A POSSIBILITY

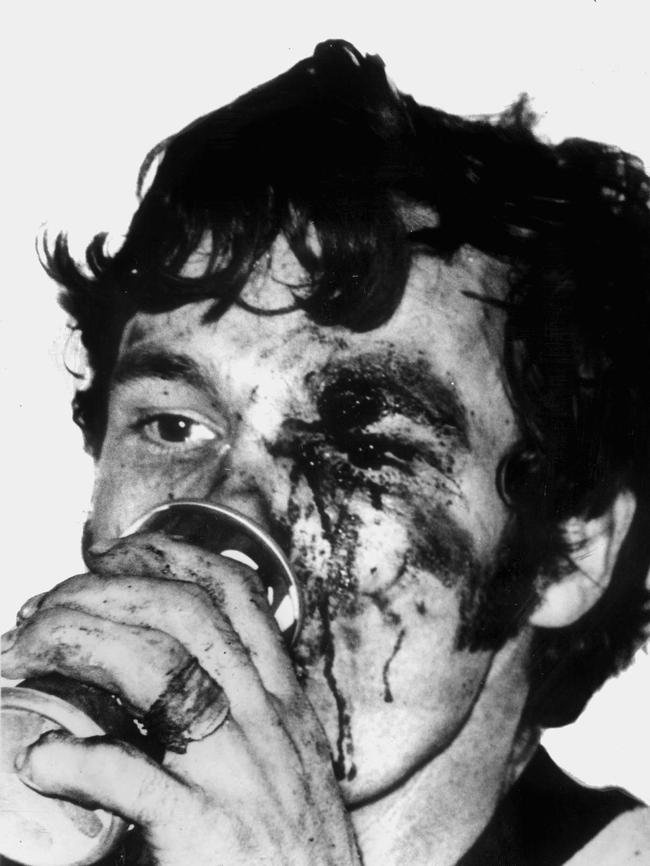

Take Francis Bourke. He won five flags with the Tigers. Folklore remembers him for a bloodied eye, when he prowled the field like an angry extra from a horror movie. Or for the time when he broke his leg and kept playing.

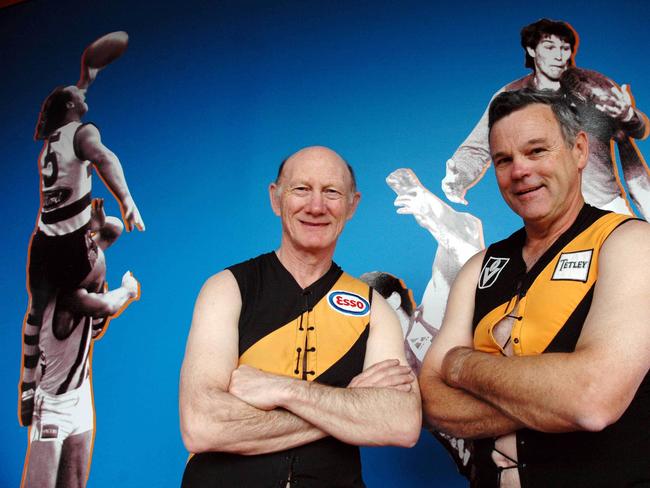

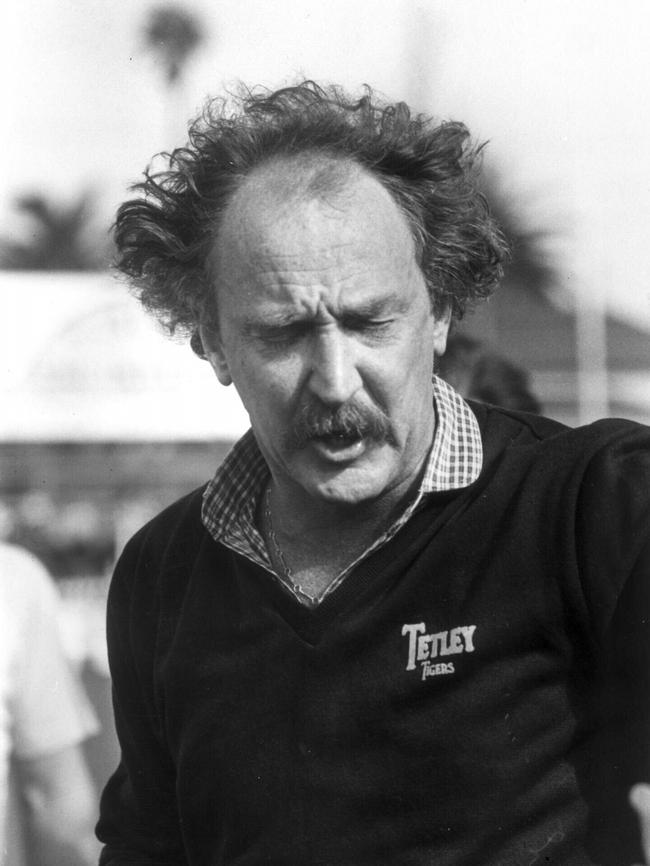

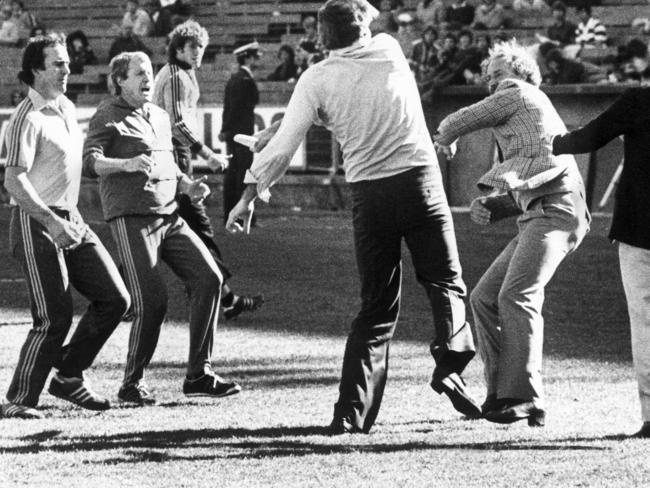

Bourke is a thinker, the middle link in three generations to play at Richmond. He coached Richmond to its last grand final, a loss, in 1982. A Richmond flag is plausible, he says, arguing that “we can, no doubt about it”. “On our day,” he says, “we can beat anyone.”

RICHMOND WANTS FRIDAY NIGHT GAMES NEXT YEAR AFTER NONE IN 2017

Dale Weightman thinks so, too. He won a Tiger flag playing alongside Bourke in 1980. Weightman was 20. And naive.

His club had won five of the past 14 grand finals.

He assumed he would play many more.

Here’s the pity. The clocks stopped in 1980. Richmond’s Punt Rd office entrance boasts 10 cups on display, or an average of one almost every seven years until 1980.

Then, there are none, as if Richmond disappeared along with Fitzroy, when the competition shed its Yarra River battlelines.

Some say that Richmond, in its stubborn adherence to old world solutions, almost disappeared, too, because its strengths came to be weaknesses. Call it attempted suicide.

Weightman and Bourke, along with Tom Hafey and Jack Dyer, remain as the Tiger touchstones. They’re pegged to disco music or the Vietnam War, or further back to the threat of the Japanese invasion. No Richmond team of the computer age has clambered to join them.

Dyer lived in Docker St, close to the street now named after him, where an apartment recently sold for almost $5 million. He dates to the Depression, when factory walls crowded squat verandas.

He was a hulking force for hope (and shattered collar bones) who became a Church St milk bar owner and media star. The youngest is Weightman, who sounds youthful for his 57 years. “It doesn’t seem it, it was a long time ago,” he says of Richmond’s most recent flag.

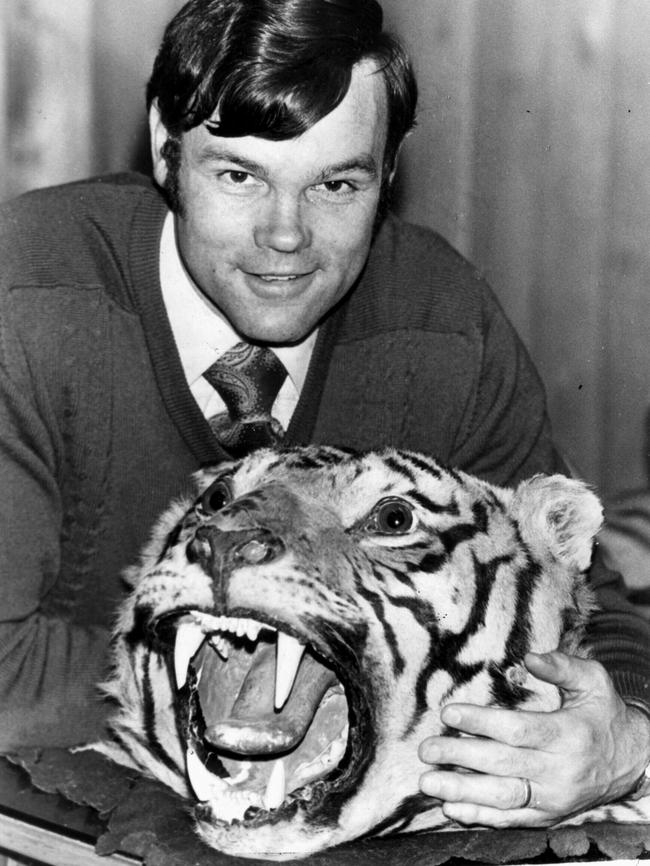

Tony Jewell was the 1980 coach. For many years he told his grandchildren that their Richmond memberships were “character-building”. Now they may be more pleasing. He says Richmond’s tackle count and forward pressure this season can withstand finals.

“Why not?” Jewell says of a flag. “I don’t think we fear other clubs. There’s no reason why we can’t.”

This is something else, such talk. It demands belief, and it is bolstered by adjectives not usually associated with Richmond, such as “sturdy” and “sustainable”, to describe its game style.

Since the early ’80s, the marriage of Richmond and triumph has spluttered like the couplings of reality television. It’s never seemed lasting: it has lived only in fevered thinking. Weightman, the relationships manager at Richmond, marvels at the supporters’ dedication.

Membership numbers have hovered above 70,000 for four years, despite a “very poor” 2016 that prompted — as failure does at Richmond — yet another board-level coup attempt.

At Richmond, frustration has long played as its own sport, and in itself has brought the kind of bloodletting and empty promises and needless loss that thrived in Caesar’s Roman Senate.

The fans have suffered — and adapted. Richmond cheer squad chairman Gerard Egan confesses to magnifying glimpses of hope beyond reality. He is referring to a kind of coping mechanism which pushes aside inconvenient facts — and lends itself to mockery. Egan, like so many Tiger fans, is still traumatised by Richmond’s preliminary final loss to Geelong — in 1995.

The club has won two finals since 1982. There is a wider acceptance that a finals win — elusive since 2001 — is the measure of Richmond’s supposed steel this season. “You just need things to go right for you on the day,” Egan says. “For the first time in a long, long time, there’s this sense that yeah, it could happen. And I don’t know if I’m ready for it.”

***************

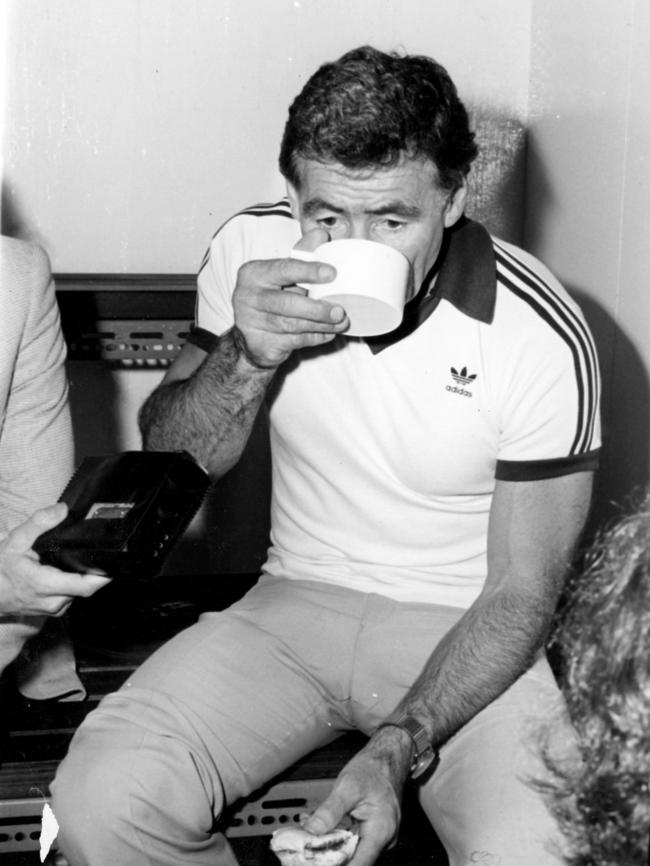

BRENDON Gale took over as Richmond chief executive in 2009. His tenure was lauded as the club’s chance at redemption.

He boldly spoke of a five-year plan, a dirty phrase in recent Tiger history, and he nominated the goals of overcoming debt (tick), doubling membership (just about) and three finals series in five years (three in six).

Gale blends modern and old, grit and reason. He was a law student when he came to Richmond as a player in the late 1980s, a grandson of Jack, who played three games for Richmond in 1924.

Gale played in 133 losses during 244 games at Richmond. He recalls a handful of finals, as well as rattling tins at intersections. He “begged” to save the club.

In 2014, he sat high in the stand for the final home-and-away clash against Sydney. Richmond needed to win to sneak into the final eight. The season was Richmond at its most befuddling — mounting losses, then mounting wins.

Throughout the last quarter, Gale rubbed his face and scratched his hair, as beholden to the outcome as the most crazed fan. Tiger tribulations had been the backdrop for most of his adult life. Gale is asked to launch books of history. When he accepted the Richmond role, he applied his knowledge of the club’s past in unpicking the reasons for its “collective failure”.

He identified the need for stability. Continuity is the main reason he projects ahead, as well into the past, in grappling with questions of today.

He regularly receives demands to “grow a new set” or “sack the lot of them”. He understands fans’ anger in difficult times, and ascribes “something uniquely Richmond” to the passionate invocations.

Perhaps it’s a throwback to better times, when loyalty, ruthlessness, and charismatic figures dominated the club. Through the 1960s and ’70s, Graeme Richmond recruited far and wide. Hafey drilled players hard. Their ways worked, Gale says.

“Since then the game has modernised and corporatised,” he says. “I still believe football clubs are clubs, but they’ve got serious corporate dimensions and that management behaviour doesn’t lend itself to good decision making.”

Richmond fell into a poaching war with Collingwood, which seemed more about fixing up Collingwood than Richmond. Coaches got sacked — Jewell, then his replacement Bourke, in tenures axed amid sniping and loss.

Someone has figured out that 10 of the 11 coaches since Bourke have never coached again. The brief appointment of Alan Bond as president in 1987 exposed a club that did not know what it was or what it was trying to be. Richmond came to be known for misfortune and parody.

Gale articulates notions of a “shared journey” and “shared sense of mission”.

“This is a highly volatile, highly emotional environment at a club like Richmond,” he says. “It attracts an enormous amount of interest, good, bad and otherwise, positive and negative. It’s important to provide a very stable platform, particularly at board and senior management level because that actually enables change.”

After finals’ appearances (losses) in the three seasons from 2013, Richmond bombed last year. A supporter group boasting former premiership players demanded a board spill. Focus on Football rumbled about poor results and wanted to tinker with game plans.

Gale says the failed push was symptomatic of an earlier Richmond age.

“It was a bit embarrassing,” Gale says. “I understood people’s anger, and they were entitled to be angry and this was a representation of that sentiment. But it didn’t reflect well. It had no impact on the machinery of the club.”

He looks briefly affronted when asked about the club’s grand final prospects. Of course we can, he replies. But he knows that daring to believe is harder for Richmond fans. The hurt of hope at Richmond has been his cross to bear for most of his professional life.

“The difference with Richmond is the club is such a historically ambitious club,” Gale says. “It was a club of the poor, and it was an expression of ambition and civic pride from day one. And it’s been a relatively successful club through history. It hasn’t saluted since 1980 but that ambition is still there. So when it’s not met, it can be a bit bumpy.”

**********

JOAN Chapple has surfed every Tiger ripple since the 1920s. She was a Swan St grocer’s daughter when the Depression pinched. Then, life got tougher. She was six when her father died.

Her fallback has always been football. Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher, obviously knew something about our game. The Tigers for Chapple, like other clubs for other fanatics, have served as her power and pleasure and pain.

Her first grand final was 1943, when patrons could buy a ticket on the morning of the match. Richmond led the Princes Park game by five points, she recalls, and Essendon had the ball deep in the forward line, when the bell finally rang.

She has watched six flags in all, until the era when the “administration stuffed us right up”. “The coaches they picked, oh God,” she says.

Chapple’s 90 now, going on 70. Each day, she toddles from her Punt Rd home to the club, one Richmond museum to another. She helps wash and clean. Gypsy, her blue heeler, wanders the rooms at will.

Chapple goes to each MCG match alone now. Her friends have moved

or died. She worries about her boys and their finals nerves, as all Richmond fans do. They’re good enough, she explains. And she’s certain she will see another flag, this year or next.

“I couldn’t imagine it,” she says. “But it would be marvellous.”

RICHMOND FACE $2.8M GAP ON NORTH MELBOURNE’S HUGE DUSTIN MARTIN CONTRACT OFFER