Two teen suicides, one school, seven weeks apart

They were the tragedies no one saw coming. Two teen boys at a prominent Brisbane bayside college tragically took their lives within weeks of each other this year, rocking the school. There were no warning signs, one day Jonah Waterson went for a ride and never came home. Now his family and the school bravely speak.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Two suicides. One school. Seven weeks apart. Tragedies no-one saw coming.

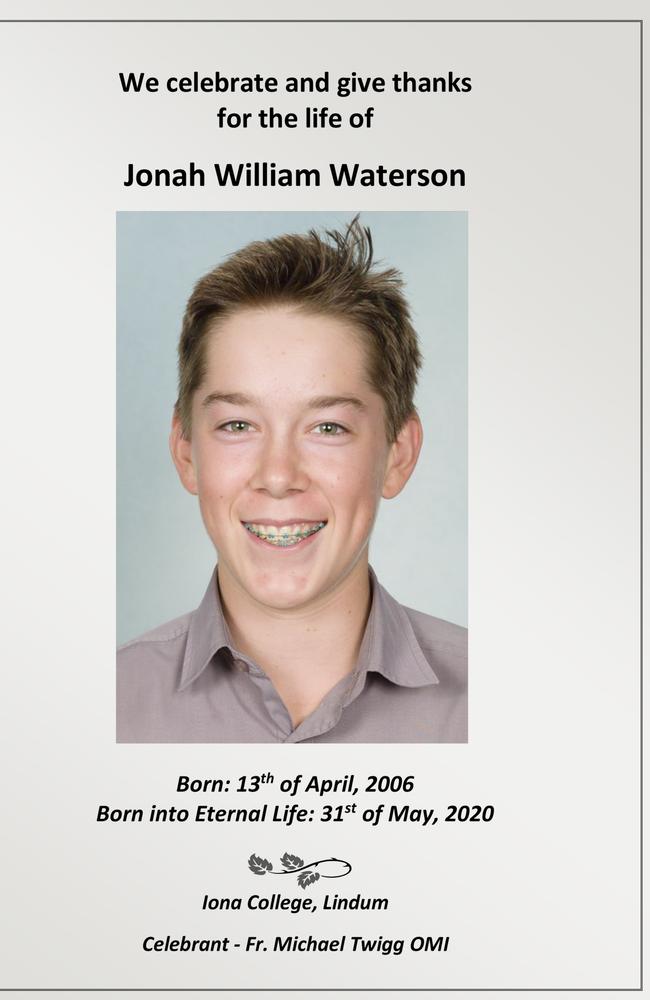

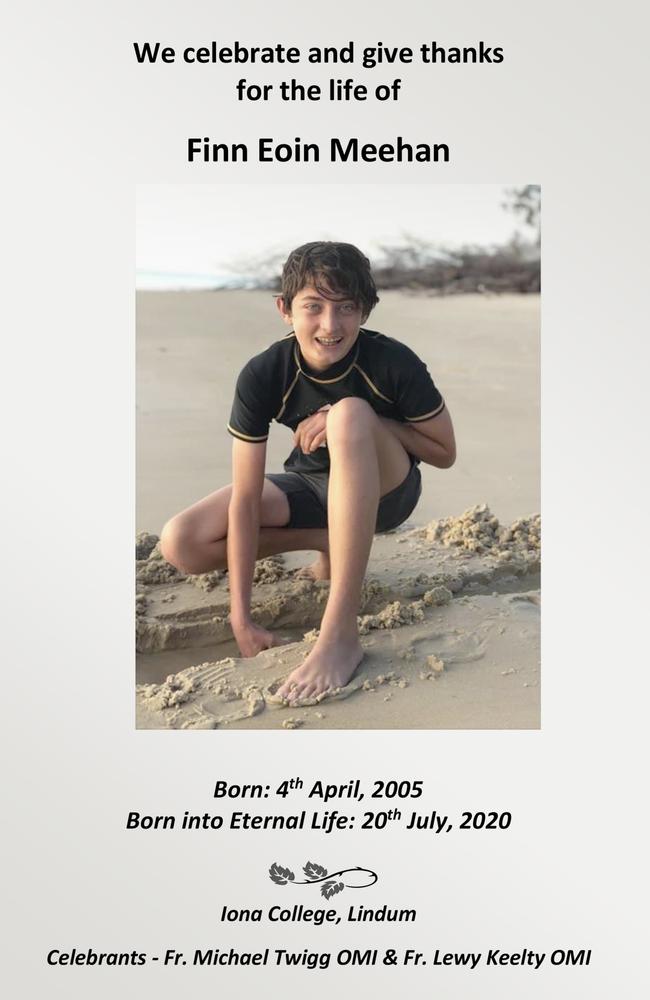

Jonah Waterson, 14, and Finn Meehan, 15, were “good” kids, happy, engaged and proud to attend Iona College on Brisbane’s bayside.

They came from close-knit families, had smiling faces, lots of friends and a solid footing in the community.

They were loved. Then something went wrong. Something in this world became too much for them.

For Queensland’s largest independent Catholic school which, in its 63 years has not had any student suicides, let alone two in quick succession, it is “a diabolical mystery”. It is this, and more.

Brave teen's powerful message after friend's suicide

Urgent measures needed to stop youth suicide

The unrelated deaths of these two “beautiful young people” reflect a society that is failing some of its children, leaving them unable to see a future of living well and growing old.

If youth suicide was at concerning levels before COVID-19, it is now hurtling towards catastrophic, with national mental health organisations predicting a spike of up to 50 per cent.

In Victoria alone, hospitals have seen a 33 per cent increase in young people presenting to emergency for incidents of self-harm over the past six weeks, compared to 2019.

These are the reasons Iona College and one grieving family are speaking out, to make Australia wake up and take action.

Suicide is a conversation we need to have. And we need to have it now.

Peter and Fiona Waterson saw no warning signs that their darling son Jonah was about to suicide. Not one.

Looking back, they wished they’d asked, “Are you OK, mate?” because maybe, just maybe, that would have saved his life.

The thing was, Jonah Waterson was a picture of health and happiness.

Those changes in behaviour the experts say to watch out for – the withdrawal from family or friends, the loss of enthusiasm for life, the emotional outbursts – Jonah showed none.

His heartbroken parents could not have missed what they could not see. On Sunday afternoon, May 31, the Year 9 student went for a ride on his bicycle and never came home.

“He was such a happy kid,” says Fiona, 53, wiping away tears she apologises for being unable to stop.

“He didn’t show any sadness; they say boys (having suicidal thoughts) withdraw, but no. I kissed him goodnight every night, had eye-to-eye conversations with him, we ate dinner as a family, and I’d kiss him goodbye in the mornings before school. “You’d think, as a mother, I’d pick up on something.”

The Watersons’ three-bedroom brick home in Wynnum West is exactly as it was when Jonah left. His basketball hoop is out front, his bedroom untouched. A photograph of his beaming face, as an adorable four year old, with older sister Georgia, sits on a console table in the entry, in a frame with the word “dream”.

There is another photo, which Fiona places on the coffee table, taken two weeks before his death. Jonah is grinning big at his sister, showing off the teal green braces his parents say he was “so proud of”.

It is an irreconcilable image.

“I thought we had a charmed life,” says Peter, 52, state maintenance manager for Goodlife Health Clubs.

“And then Jonah did what he did; it was massively out of character for him.

“We had no knowledge of dealing with that sort of thing. Jonah was just happy, that’s the simplest way of putting it.

“He could be quiet. He was a guy who didn’t like the limelight, but when he got into a comfortable group he would rise to the top and be joking and carrying on. He loved his AFL, basketball and volleyball.”

Born on April 13, 2006, Jonah was a young 14.

“If someone had a crystal ball and said Jonah was going to take his life, there is no way I would have believed them, no way, no way,” Fiona says softly, shaking her head.

“The month before, he was 13, how do little kids even think like that?”

On the morning of his death, Jonah awoke to his favourite breakfast.

Georgia, 18, and taking a gap year after graduating from Lourdes Hill College, had rustled up blueberry pancakes, which the foursome enjoyed around the kitchen table.

Jonah had been in particularly great spirits all week, having gone back to school for the first time since the March COVID shutdown.

“He was probably the happiest I’ve seen him,” Fiona says.

“He didn’t enjoy COVID. He’d get his work done at home then go outside and play basketball, and at one stage he said, ‘Oh Mum, this is terrible’, but his first week back at school, he was like a different kid.

“He was really looking forward to basketball trials, to volleyball, to everything.

“He asked me if I thought he’d make the A’s and I said, ‘It doesn’t matter, mate, as long as you’re having fun’.”

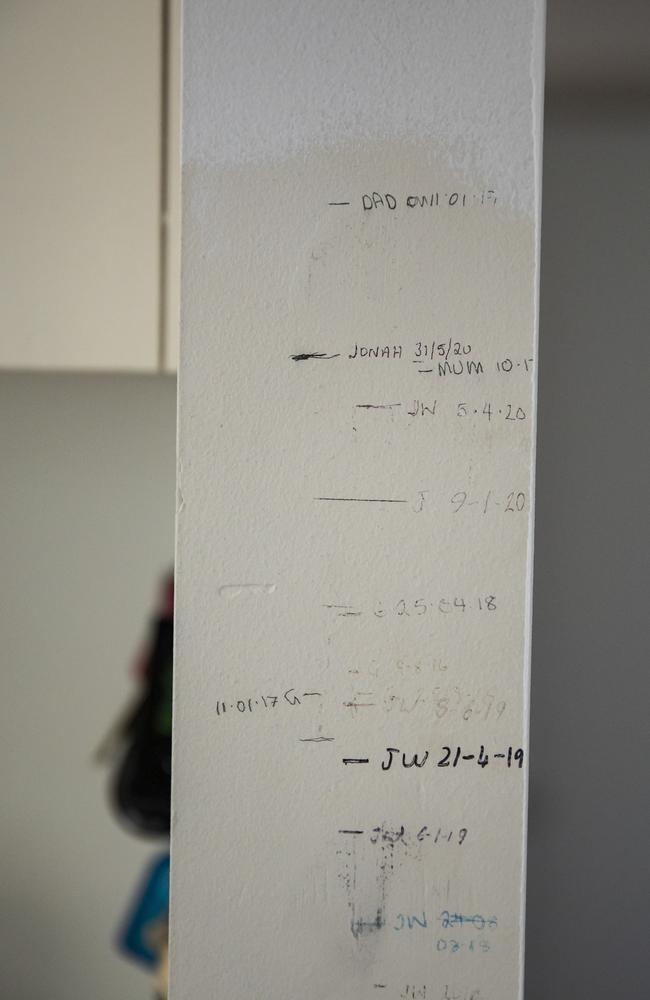

After helping wash up, Jonah asked his parents to measure how tall he was, as kids are wont to do ahead of an adulthood that can’t come quickly enough.

The mark where Jonah stood, ramrod straight, remains on the kitchen wall, beside his mother’s, a smidgen over 173cm.

“He was stoked to have pipped Mum,” Peter says. “None of it makes sense, why would you then go and do that?”

“He always wanted to be taller than I am,” Fiona adds, “and Jonah had size 12 feet so he was always going to get there – he was pretty chuffed, and I was like, ‘Well done, son!’.”

Jonah’s best friend then called and asked if the pair could play Xbox so Jonah went into his bedroom, where the gaming console had been relocated during lockdown so Fiona could do her bookkeeping job from home with fewer distractions.

“He’s really loud when he’s on Xbox,” she says, “and that morning I was actually in his room for probably an hour with him because his aunty had given him some hand-me-down clothes which I’d washed and was putting away.

“I was playfully ducking in front of him, and was he saying, ‘Oh Mum, get out of the road’.

“Then I went off and did some more laundry, and got a text from his AFL coach to invite him to come to the oval after lunch for a kick with a few of the boys.”

Jonah had notched up more than 130 games with the Morningside Panthers, where his mum is treasurer of the junior club and his dad takes team photographs.

“Jonah sort of went, ‘Do I have to? Can I go for a ride on my bike?’,” says Fiona. “And I said ‘Yes you can, but we’re also going to go to the oval because I haven’t seen anybody for ages, you haven’t seen anybody different for ages’, and he said, ‘OK, righto’.”

The last time Fiona saw her son alive he was sitting at his desk, scrolling through his phone and eating two-minute noodles.

“I was going to go in there,” she says. “But I thought, ‘No, I’ll just let it be’.”

Around 12.30pm she noticed the garage door was open.

“I asked Pete and he said Jonah had gone for a ride and would be back at 1 o’clock … and that was it.”

No-one suspected for a second that Jonah could be in trouble.

At 1.50pm, Fiona, who’d hoped to be on the way to Morningside by then, asked Georgia to try her brother’s mobile. The phone rang out.

Still not overly concerned, Fiona called it herself, five minutes later.

A police officer answered.

“He asked who I was, what my son was wearing, and I knew then it was not good at all, and I gave the phone to Pete because I just couldn’t cope,” she says.

“I had questions of my own,” Peter says. “Like, ‘Why have you got Jonah’s phone, and where did you find it?’ because we’ll go looking for Jonah, but the police just said they’d get back to us.”

By the time officers arrived at the Watersons’ home, around 4pm, Peter had been driving around searching for his son. Fiona had been calling every hospital.

Police showed them a CCTV image of Jonah, minutes before his death, and the couple’s worst nightmare began.

“The police were surprised,” Peter says. “They were like, ‘He’s not on our list’ (of vulnerable kids). Until that point, we thought Jonah had been in an accident, but they said, ‘No, it appears to be deliberate’.”

Late on Wednesday, June 3, the coroner confirmed the cause of death as suicide.

Police probes into Jonah’s phone and computer usage, and a search of his locker at Iona College, have shed no light on why a young life ended so abruptly.

“When you think of suicide, you think of a troubled kid, someone who has problems, whether it’s family, school, friends, something’s got to be going on,” Peter says.

“All we’re left with now is wondering, how has that happened to Jonah?

“To me, it doesn’t make sense (to blame) COVID – it didn’t affect us too much financially because my hours were only temporarily cut back, and Jonah’s sport had resumed and he’d had an awesome week at school.

“But by the same token, it doesn’t make sense for any other reason.”

Seven weeks after Jonah’s death, the abject grief of one Iona College family was revisited on another.

Year 10 student Finn Meehan, a keen sailor with the college and the Royal Queensland Yacht Squadron, suicided on July 20. His parents John and Lisa Meehan have decided not to speak publicly about the tragedy at this time.

Father Michael Twigg, rector of the college, describes the loss of two precious children as “a mystery, a diabolical mystery”.

“They were both prototype Ionians – run-of-the-mill good kids, smiling faces, engaged, involved, no trouble, just beautiful young people,” Fr Michael says.

Their funerals were held on school grounds, in Our Lady Help of Christians Chapel, and followed another shock loss for the community after former student Zachary Robba, 23, was killed by a shark in April.

Fr Michael, 49, who has been at the helm of Queensland’s largest independent Catholic school for five years, and is himself an old boy, led the services, which were live-streamed due to COVID-19 restrictions.

“In the middle of three very big sadnesses, you have this balancing act between wanting to join the chorus of ‘2020 is a write-off and isn’t it horrible’ and our natural inclination to be steely determined people of hope.

“The hard part with sudden death by suicide is you don’t get an answer.”

He says the funerals for Jonah and Finn were “not about how they died, but how they lived”.

“If we didn’t do for them what we did for Zac, then we are saying the way in which you die determines what sort of farewell we give you.

“Every layer of the school was standing with them; around 400 boys formed a guard of honour outside and our groundsmen lined up their tractors, in a deep show of respect.”

Fr Michael, who has been supporting the grieving families and managing communications with parents who “have no words” to explain the inexplicable to their children, says it is inevitable to ask, “What did I miss?”

Inevitable yet unyielding, particularly as there were no outward signs of a personal battle, from either boy.

“There was no apparent bullying at school, there was no disruption at home, these boys were in deeply loving families, and it still wasn’t enough – that’s what makes it so frightening,” he says.

“However, if the only question asked is, ‘What did I miss?’, then essentially that question could be asked for decades, and potentially never get an answer, including for people who loved them most.

“But if the question is, ‘What did I give?’ then there is an answer, an answer that can bring comfort to families, to know that they gave full love.”

Iona is not a chest-beating school.

Its location, on 28 sprawling hectares on a hill 16km east of the CBD, might imply privilege but its DNA says otherwise.

Iona is run by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, an order founded in France in 1816 and which prioritises assisting the abandoned and marginalised, particularly young people.

Fr Michael, a passionate “Oblate”, is unfamiliar with the recognition his school is now receiving. “We’re not used to people saying, ‘However tough we’re having it, I’m glad we’re not that school’,” he says. “Well, we are that school, and we can’t say, ‘Nothing to see here, everybody’; it has to be challenged.

“The ramifications of not talking about suicide are too great.”

For Fr Michael and his leadership counterpart, lay principal Trevor Goodwin, the response goes beyond the gates of their school of 1750 boys – to educators and parents around Australia as they grapple with a national youth suicide crisis.

Fr Michael says while it is impossible to connect any COVID-19 fallout to the deaths of Jonah or Finn, the overall spike in youth suicide “has to mean there is something in the air that’s different”.

“Schools have told us they are hyper-aware, especially with lockdown and the limitations of connecting online. Face-to-face is so important and it’s why schools are crucial in the COVID response,” he says.

“Every school in Australia is walking a journey with vulnerable kids right now.”

Grim statistics and dire predictions would suggest he’s right. Lifeline has taken more calls for suicide prevention help since March than in any other time in its history, recording a rise of up to 33 per cent.

Professor Ian Hickie, of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre, has warned suicide rates could soar by up to 50 per cent due to the lasting impacts of COVID-19, while Professor Patrick McGorry, founder of youth mental health organisation Headspace, has referred to a “perfect storm” of lockdown, unemployment and hopelessness for the future.

Fr Michael gets it.

“For us at the moment, we truthfully don’t know if we’re in the middle or the end of the storm,” he says.

“Queensland wouldn’t be as impacted as it seems Victoria and other places are, but what this shows is we just don’t know where the impact is and how deep it goes.

“If you view it through the lens of a young person, they’re told there will be debt for decades, their ability to get and keep jobs diminished, and with a ‘missing year’ potentially of their learning, they’ll always be behind.”

Adding to this “destabilising of the society we knew” is the innate impulsiveness of young males. According to government figures, suicide is the leading cause of death for Australians aged 15 and 24, and three-quarters are male. In children under 14, suicide ranks fifth, after car accidents, congenital conditions, brain cancer and drowning.

Since returning to Iona College, 28 years after leaving as a student, Fr Michael has prioritised mental health. In 2018, he implemented the internationally renowned Visible Wellbeing program, by University of Melbourne psychology professor Lea Waters, to help students and staff “see wellness in action”.

Last year he appointed a safeguarding officer, whose job includes running the Seasons for Growth loss and grief education program and a respectful relationships course for Year 12s.

This takes the number of counsellors to three, building on the college slogan, which Fr Michael instigated in 2018, of “never worry alone”.

Yet, as he says, “For all this significant investment, there is no guarantee … there can be a trajectory people don’t see”.

Fr Michael has been at pains to find appropriate strategies to help his community.

In communications to families and on the advice of Headspace, he has employed medical analogies – of emotional cancer and heart attack – to try to unpack the complexities of suicide.

“The battle somebody could be suffering inside could be really quick, and not demonstrated in any identifiable way, and that’s the big, frightening thing for parents,” he says.

“With cancer, there is a journey and a team of people fighting it. With a sudden heart attack, there is no journey, but in both cases, some sufferers survive and some don’t.

“This provides an understanding of how something could come from nowhere.

“It’s the toughest gig for a parent – to know when to step in, or not step in on an issue.

“If you step in too early are you causing resilience problems? If you step in too late, is it too late?”

Iona College has been inundated with messages of solidarity from schools right across the country.

More than 60 have reached out, including Brisbane’s St Laurence’s, Padua, Villanova, Marist Ashgrove, St Patrick’s, St Peter’s and Ipswich’s St Edmund’s, all members of the Australian Independent Colleges (AIC) sporting network.

So have Catholic girls’ schools All Hallows’, Lourdes Hill and St Rita’s, and Iona’s neighbours, Moreton Bay Boys’ College and Moreton Bay College, Catholic primaries Guardian Angel’s, St John Vianney’s and St Oliver Plunkett, and state schools in Wynnum, Manly and Alexandra Hills.

Fr Michael says the Iona Year 10s were so moved by the support that one boy suggested handwriting cards of thanks “since those messages were for us”.

Some cards were read out at other colleges’ assemblies, and when inter-school sport resumed last month, boys from opposing teams came together around that shared experience.

Moving forward, Iona is evaluating student suggestions to make it easier for younger boys to reach out.

A huge sign, bearing those vital words “never worry alone”, is being erected on one of the buildings.

Teaching materials have been reviewed, including Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and next year’s The Addams Family musical postponed.

“We’re not spooked by death but we have to be really conscious of what we’re using as tools to teach kids, of what is going into the well that kids are going to need to draw on when those storms hit them,” Fr Michael says.

“There are lessons to be learned at Iona, and we don’t want to come off as any kind of expert but we also don’t want it to appear we’re flying blind here, and if we can be a companion on the journey to other schools facing mental health issues, then good.

“Everybody in society has a role to play, and if we can empower young people to talk about wellbeing, to realise there is nothing to be ashamed of if you’re on shaky ground, if we can build stronger teams, then that means parents don’t have to worry alone.”

Peter and Fiona Waterson are not letting go of Jonah.

“Once you become a parent, you’re a parent for life,” says Fiona, who counts her next major task as deciding what to do with his ashes, currently at Hemmant Cemetery.

“Tackling his bedroom is way, way down the track,” she says.

For now, she and Peter are staying connected to the life they knew with Jonah.

Fiona drives her son’s best friend to AFL training and watches their under 14s play.

“It makes me happy to watch the boys, I mean, I loved watching Jonah play,” she weeps.

“He’s just got such great friends.”

Fiona is continuing as junior club treasurer and Peter is there too, with this trusty camera to capture all the action.

“Jonah would never have wanted us to be sad,” she says.

Iona College has invited the family to basketball games that Jonah would otherwise have played, and Fiona is considering volunteering at the canteen.

“The school has been absolutely wonderful, and so have the Panthers and wider AFL community,” she says.

Shortly after Jonah passed, AFL legends Wayne Carey and Brian Taylor and fellow Channel 7 sports presenter Hamish McLachlan made a video to encourage young Panthers to “have the conversation” around mental wellbeing.

Carey urged the boys to speak to their teammates, parents, aunties, uncles, anyone they could, and to “win the season for Jonah”.

There isn’t a week that goes by that one of Jonah’s many friends doesn’t visit the family home to check on Peter, Fiona and Georgia.

“Sometimes they bring chocolates, sometimes they come to talk, and sometimes they just come to listen,” Fiona says.

The Watersons, who moved to Brisbane from country Victoria for the weather and lifestyle 12 years ago, are slowly finding their “new normal”, as Fiona puts it.

Back in the office of Snap Fitness gyms where she handles the accounts, Fiona gets counselling and meditates, and every week the family does restorative yoga together.

Peter says Georgia has struggled with the loss of her baby brother but “is a bit of a soldier”.

And he counts himself as blessed.

“I’m pretty lucky, whenever I think of Jonah, I just get happy thoughts, there simply are no bad memories,” he says.

“He was a happy, smiling kid. We’d be piss-farting around the table and he’d pretend to ‘crack the sads’, and then he’d try to hide that smile but it would always come out.”

On the night of the worst Sunday of their lives, amid their enormous shock and pain, Peter and Fiona sat with Fr Michael at their home and considered how to communicate what had transpired to the Iona community.

“It was hard,” says Fiona. “But we thought about the other boys. This is their fun-loving mate who would do anything for them, and then he does this, he takes his life.

“How do you go from sitting next to your mate in class one day to him not being there ever again? I mean, I struggle to process it, but they’re only 14.”

As Catholics, Fiona and Peter believe they will see Jonah again, in heaven.

But Jonah is going to have to wait, Fiona tells her son, looking at his achingly familiar smile in the photo on the coffee table.

“I know I will see you again, but it’s not going to be for a while, sorry mate.”

If there is anything positive, anything at all, to be gained from the Watersons’ pain, it’s helping other kids, other families.

“Had there been signs, we’d have probed a bit more,” Peter says. “Now we look back and wonder if the most trivial, insignificant things could have meant something.

“You just have to make the conversation around suicide happen, even when there are no signs.

“As bad as all this is, we know there have been thousands of conversations with boys, and girls, since Jonah, and we want there to be thousands more.”

HOW TO ASK THAT QUESTION

It’s natural for parents to be anxious about raising the subject of suicide, but talking about it does not plant suicidal thoughts in a child’s head, according to Sara Bartlett, from leading mental health body Everymind.

“It is better to reach out than avoid worry about getting the conversation ‘wrong’,” Bartlett says. “If you feel a person may be at risk, ask the question directly: ‘Are you having thoughts about suicide?’ and be prepared for the answer, whatever that may be.

“Ultimately, it’s about listening and not trying to ‘fix’ a problem, and then knowing where to go for 24/7 support.”

If someone says he or she is not thinking about suicide, opening the communication lets them know you are there if things ever get tough.

“It is a big misconception if you have a conversation with someone it will cause them to suicide,” Bartlett says.

“The point is to encourage people to seek help, and everyone has a role to play within the community, families and friendship groups to break down the stigma.”

Kristen Douglas, from Headspace Schools, says suicide is rarely the result of a single factor. Headspace, which has drop-in centres across Australia, encourages family and friends to follow three steps.

● Notice: changes in behaviour, including eating, sleeping, and withdrawing.

● Inquire: Use sensitivity and compassion when asking how a child is feeling.

● Provide: Information on support, including talking with a relative, friend, or GP.

If you or anyone you know needs help:

Lifeline 13 11 14

Kids Helpline 1800 551 800

Headspace 1800 650 890

Beyond Blue 1300 224 636

USEFUL RESOURCES:

healthdirect.gov.au/youth-suicide

Originally published as Two teen suicides, one school, seven weeks apart