Queens Mary’s war service tragedy

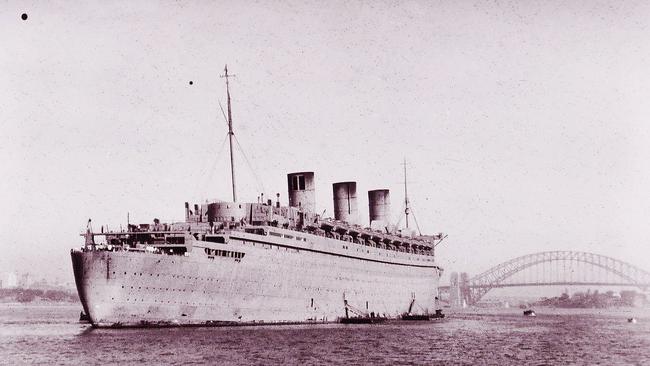

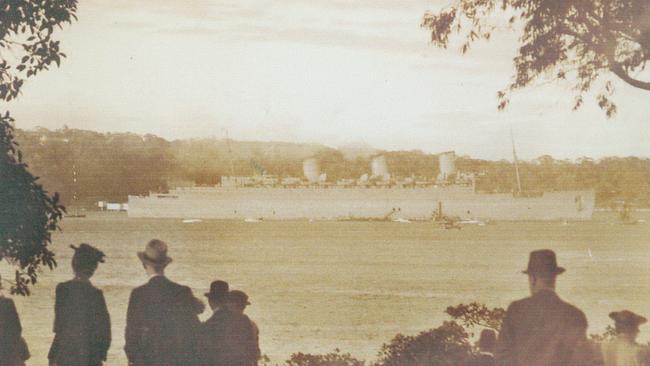

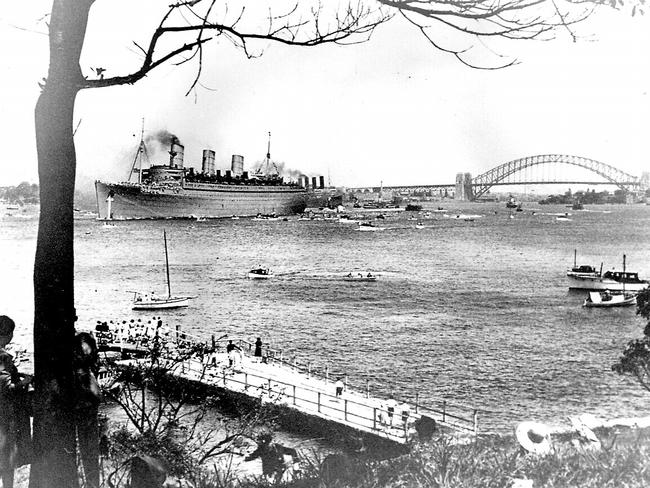

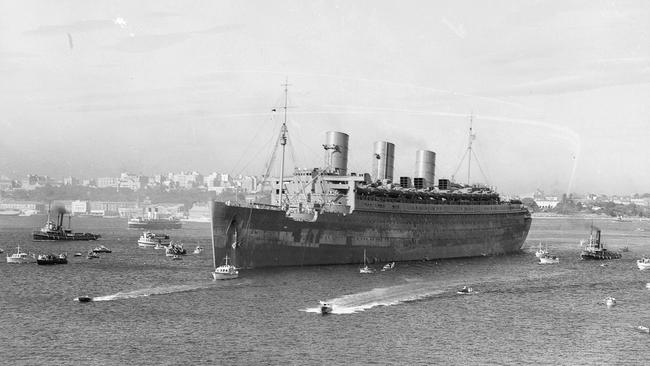

The arrival of giant Cunard liner Queen Mary in Sydney in early 1940 was supposed to be a closely guarded military secret, but newspapers wrote of her impending visit, also noting deep dredging near a harbour wharf.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE arrival of giant Cunard liner Queen Mary in Sydney in early 1940 was supposed to be a closely guarded military secret, but newspapers wrote of her impending visit, also noting deep dredging near a harbour wharf.

The Queen Mary sailed into Sydney Harbour on April 17, 1940 to spend two weeks being stripped of the last of her luxuries and refitted as a troop carrier, before again steaming north with 5000 Australian troops.

She returned to Sydney in March 1942, carrying American troops to the South Pacific. later in 1942 she made four voyages, each taking about five days, from New York to Gourock, on the west coast of Scotland, each time carrying more than 15,000 US troops to join the European war effort.

German Fuhrer Adolf Hitler had offered a £250,000 reward to the submarine captain who could sink the Mary, as well as the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves.

But when disaster struck off the northwest coast of Ireland at about 2pm on October 2, 1942, the 338 victims were all British seamen on HMS Curacoa, in a tragedy officially hushed up until the end of WWII.

As the massive Queen Mary neared Ireland that morning, she had rendezvoused with the much smaller Curacoa, which would provide an anti-aircraft escort for the last leg of the voyage to Scotland.

The Queen Mary, carrying US troops from the 29th Infantry Division, was steaming in an evasive “Zigzag Pattern No 8”, at 28.5 knots (52.8km/h), to advance at 26.5 knots (49.1km/h), to evade German submarine attacks. The Curacoa remained on a straight course at a top speed of 25 knots (46km/h), so would eventually be overtaken by the liner.

The two ships found themselves on a collision course but when informed, the captains of both vessels believed the other would take evasive action, as each captain had different interpretations

of which ship had right of way.

On the Curacoa, Captain John Boutwood kept to the liner’s mean course to maximise his ability to defend the liner from enemy aircraft. On the Queen Mary, Captain Charles Illingworth continued zigzagging, expecting the escort cruiser to give way. The 81,000-tonne Queen Mary, launched in 1936, dwarfed the ageing 4290 tonne Curacao, afloat since July 1916, as the tragedy unfolded about 20 nautical miles off the Irish coast.

Curacoa seaman Ernest Watson later described how he was admiring the majestic Queen Mary when he noticed the bow was swinging toward the Curacoa. As the gap narrowed, Watson says he screamed, “She’s going to ram us.” He later said many of his shipmates had been so shocked they could not move as the Queen Mary struck broadside on, slicing through the cruiser’s 10cm armour plating to cut the vessel in half.

Watson and many other seamen on deck were thrown into freezing water. As they surfaced they watched as the stern quickly sank, with men trapped behind watertight doors. The liner, under strict orders not to stop under any circumstances to avoid U-boat attacks in such a dangerous area, had to continue to her destination. As 101 seamen were picked up by other ships, 338 perished in

freezing waters.

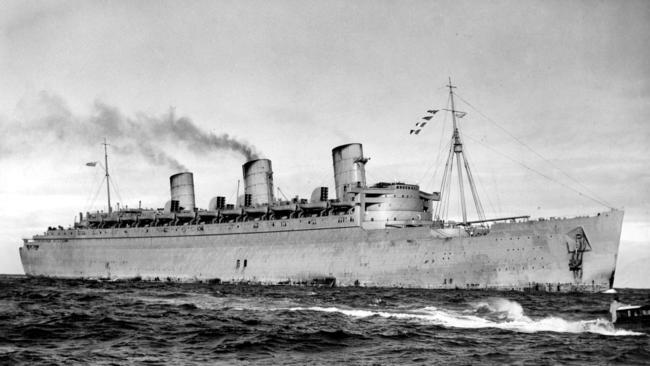

The Queen Mary, then known as the Grey Ghost for camouflage paint applied in New York during her 1940 conversion to a troop carrier, was also severely damaged in the collision. Her size and build quality kept the vessel intact and afloat, preventing a death toll that would have been eight times greater than that suffered in the Titanic tragedy.

The disaster was hushed up until May 1945 when solicitors acting for the British Admiralty applied to the British High Court to hear claims on behalf of dependants against Queen Mary owners Cunard White Star Line for £750,000. A Court of Inquiry first blamed Curacoa’s Captain Boutwood. On appeal, it was decided in February 1949 the fault lay two thirds with the Curacoa and one third with the Queen Mary. By the end of the war the Queen Mary had carried more than 800,000 servicemen between Australia, South Africa, the US, the Middle East and Europe. She had also carried prisoners of war, among them Italian prisoners sent to Australia.

On her 1940 visit to Sydney, when her destination was revealed to her captain only two days before he was to leave New York, the Queen Mary berthed at Athol Bight near Bradleys Head. Hundreds of workers from Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Company were ferried across in around-the-clock shifts to convert shops to military offices and increase its accommodation from 2140 to 5500.

Originally published as Queens Mary’s war service tragedy