Our last convicts were Irish political prisoners sent out on the Hougoumont

IN a cabin on a frigate bound for Australia, a group of Irish political prisoners penned an opus which would chisel their journey into the annals of colonial history. The last convict ship to Australia was the Hougoumont and 150 years ago this week it docked at Fremantle, WA, with 280 convicts on board.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IN a cabin on a three-masted frigate bound for Australia, a group of political prisoners penned an opus which would chisel their journey into the annals of colonial history.

They were no ordinary prisoners and it was no ordinary journey. The ship was the Hougoumont and 150 years ago this week it docked at Fremantle, WA, with 280 convicts on board.

It was the last time Great Britain shipped convicts to Australia, bringing an end to 80 years of penal transportation.

The journey, which ended on January 9, 1868, was singular; shipping convicts to the east coast had been outlawed more than 28 years before and transporting political prisoners was

also prohibited.

There were a high number of literate prisoners among the 280 convicts; most were Fenians — 19th century Irish nationalists — persecuted after the Fenian Rising the previous year.

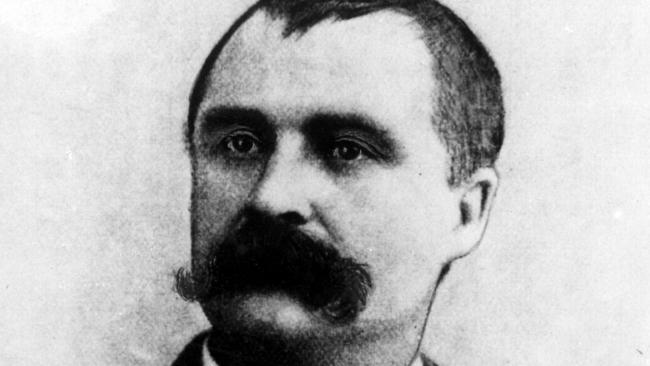

Among the 62 Fenians were writers John Boyle O’Reilly, John Flood, Denis Cashman and John Casey.

Initially O’Reilly and his compatriots were apprehensive being incarcerated with hardened criminals; they were by and large well-educated civilians who were punished for their political views.

“As I stood in the hatchway, looking at the wretches glaring out, I realised more than ever before the terrible truth that a convict ship is a floating hell,” O’Reilly wrote. “We hesitated before entering the low-barred door to the hold, unwilling to plunge into the seething den.”

Cashman, who was a young clerk when he was arrested, kept a diary of the journey in which he gives a keen insight into the sorrow felt by himself and his fellow compatriots.

“I really felt wretched — the thought of being sent 14,000 miles away from my dear wife and children … caused me to feel an acute agony that I had never before felt; and plunged my whole being into the deepest melancholy.” To cope with the 89-day voyage the Fenians established The Wild Goose, a newspaper of seven editions containing stories by the prisoners on board.

Each copy of the handwritten newspaper survives today, held at the State Library of NSW. In reading the text it becomes apparent O’Reilly, Flood and Casey used the paper to cope with their incarceration but also to thumb their noses at the British government.

“This great continent of the south, having been discovered by some Dutch skipper and his crew, somewhere between the 1st and 9th centuries of the Christian era, was, in consequence taken possession of by the government of Great Britain in accordance with that just and equitable maxim, ‘What’s yours is mine; what’s mine is my own’,” it reads. “That magnanimous government in the kindly exuberance of their feelings have placed a large portion of that immense tract of country called Australia at our disposal.

The paper was divided into sections, including a “news” and “the markets” section, which were predominantly filled with nonsense and witty banter but gave an excellent insight into the daily commotions on board. “Tobacco not to be had at any price; holders unwilling to part with the commodity, great demand for preserved potatoes and plum duff, water scarce (and of inferior quality), pork rather high than usual (and still advancing), biscuit getting livelier, chocolate a drug in the market, tea rather flat, oatmeal steady,” it reads.

“Our entire staff, ‘devil’ and all, have been fairly driven to their wit’ ends to concoct something to fill up this littler corner, and have utterly failed.” As well as contributing numerous poems, including The Flying Dutchman, O’Reilly held weekly readings of the newspaper on the ship and Cashman details in his diary how spirited the readings became.

The readings morphed into concerts, with songs, music and poetry, staged on a 165-foot (50m) ship. The last issue of The Wild Goose was penned on December 21, 1867, and in it the editors were able to guess with a degree of accuracy the final days of their voyage.

“We congratulate our readers on our rapid voyage since leaving England. It is probably that, with the continuance of such weather as we have had for some days, we may arrive in Fremantle on or about the 8th January 1868.”

Father Delaney, the Catholic chaplain on board, signed off the edition with parting words for the convicts.

“You have in your keeping things the most precious to the heart of man — things that no power can wrest from you, no matter whether your position be that of convicts, exiles or freemen — your own honour.”

After alighting the ship, convicts were sent to Fremantle Prison and in the case of O’Reilly, on to a convict camp in Bunbury. At the camp O’Reilly struck up a friendship with another Catholic priest, Father Patrick McCabe, who offered to help him escape.

On February 18, 1869, he fled the convict party and hid in dunes up the coast from Bunbury, ultimately stealing away on the American-bound ship Gazelle two weeks later.

As a result of his escape and subsequent career as a successful journalist and poet in Boston, O’Reilly became one of Australia’s most infamous convicts.

His fellow Fenians were pardoned by the British Government in 1869, but they were not permitted to return home until their sentences expired.

Originally published as Our last convicts were Irish political prisoners sent out on the Hougoumont