Patrick Carlyon: Old school routine a lesson in avoidance

THE headmaster of Camberwell Grammar School recently wrote a letter to parents. His was a difficult task peculiar to school principals, writes Patrick Carlyon.

Patrick Carlyon

Don't miss out on the headlines from Patrick Carlyon. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE headmaster of Camberwell Grammar School recently wrote a letter to parents. His was a difficult task peculiar to school principals.

RETIRED CAMBERWELL GRAMMAR TEACHER IN COURT ON SEX ABUSE CHARGES

Dr Paul G. Hicks informed the school community that a former teacher of the school had been charged with the sexual abuse of students.

Hicks took the standard approach to such unsavoury matters. He chose to not inform the school community of much at all.

The teacher, Trevor Spurritt, was “a former staff member”.

The allegations of sexual abuse were “events”. Hicks then hit trouble with details. He spoke of “events” “in the early 1970s”. This is kind-of true. The charges against Mr Spurritt date from that time — until 1991.

Hicks ploughed on. “The person” concerned “has long

since left the school”. Again, the choice of words served to deaden the reality. Mr Spurritt was a maths teacher who headed up school camps from the hippie movement to the Howard years.

Hicks explained that any form of sexual abuse is “criminal and abhorrent”. The school would offer care, support and assistance if any concerns arose. Indeed, there were six very official-sounding charters and guidelines.

Hicks did not point out that Camberwell Grammar — as with every other school — is legally bound to do no less.

All schools face deregulation if they do not follow policies and procedures to manage the risks of child abuse. Nor did he mention that all the policies now in place do nothing to ease the pain of victims of child abuse.

Hicks’s letter, in tone and content, reduced the scope and magnitude of the scandal. His was the dead hand of bureaucracy that can turn a raging bushfire to an unfavourable heat exchange.

Compare Hicks’s take with a media report last week: “Seven men have accused a private school teacher of historical sex assaults spanning two decades.”

It’s a bit unfair to single out Camberwell Grammar. It’s textbook public relations to acknowledge — and then blanket — bad news. To cast it as an ill that won’t be repeated because umpteen protections have been built into the system as a result.

It’s what big banks do, even football clubs. It’s about preserving the brand.

Yet there are risks to such an approach, especially in schools. Perceptions of cover-ups — coupled with lofty lines in integrity and leadership — run close to the greatest intellectual fraud of all, known commonly as hypocrisy.

Rewriting history also tends to offend those familiar with the past.

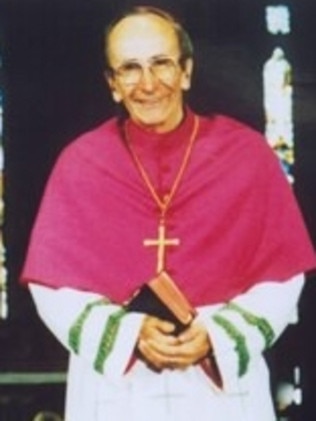

Other schools have been more brazen. Earlier this month, St Patrick’s College in Ballarat set about officially erasing Archbishop Frank Little. Holy amnesia is as easy as renaming a building, apparently. Tear down a sign and, presto, Little ceased to ever exist.

Another school near Camberwell Grammar has suffered scandals. There, a former teacher committed suicide before a court hearing, prompting that school’s principal and his deputy to extol that teacher’s “extraordinary legacy”. He was “the best educator we have known”, they said, overlooking a string of alleged abuse victims and the reflexive shock and revulsion that still flares whenever they speak about setting examples.

At Camberwell, the recollections of former students are more vivid than Hicks’s abstractions. They are laced with a lingering sense of disbelief. What Hicks reduces to “a former staff member” and “over 40 years ago” remains currency in phone calls, texts and dinner conversations for generations of old boys.

It wasn’t every one and it wasn’t all the time. But it was always there. It seems that the grapevine was the students’ only protection against the entrenched behaviours of several teachers.

The question now is why other teachers did not intervene on the students’ behalf. Some knew. They must have. Most others did. Where was their integrity and leadership?

Camberwell Grammar boys got chances that many kids do not.

I, as one of them, will always be grateful to my year 12 English Literature teacher. Most old boys speak fondly of their school years, recalling barmy cricket coaches and sly ciggies in the KAO change rooms, perhaps, but also a realm where teachers were “Sir” and respect for authority was assumed.

But several teachers blot recollections from the 1970s and 1980s. The instructions on school camps to swim naked for house points. The safaris when kids would play in mud, naked, while one of several teachers would film, naked. Two or three teachers lingered in showers. What was thought weird then has another label now: criminal.

One student, who is 45 now, tells how a teacher approached him from behind and put his hand on his shoulder. The boy spun around and knocked the teacher’s arm away. His older brother, in a warning repeated in many families, had said of this teacher: “Whatever you do, stay away from him, he’s bad news.”

These tales got told over and over in the Camberwell Grammar schoolyard. They have been told over and over in recent weeks. None of them was reported at the time, as Hicks points out in relation to the Spurritt allegations in the early 1970s.

These stories thrive in the unofficial oral history, as told by the students who received lessons in integrity and leadership — and dodging the dodgy teachers.

These kids were not there to further a brand or a business.

They went to school to gain knowledge and values.

Actions then, as correspondence now, suggests that this simple truth eludes those who are supposed to know better.

Patrick Carlyon is a Herald Sun columnist