It’s easier to silently disagree than engage when the public battlelines favour the shrill

The biggest issue in the debate over the Shrine, Australia Day, and the Manly pride jerseys is that no one wants to be told how we ought to feel.

Patrick Carlyon

Don't miss out on the headlines from Patrick Carlyon. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A nearby cake shop decorated itself in political advertising during the recent federal election. Vote for this bloke, the signs said.

Was this very wise? The cake shop stance forced a choice that many people seeking their innocent fill of cream and sugar would have liked to avoid.

You were with the cake shop people or against them.

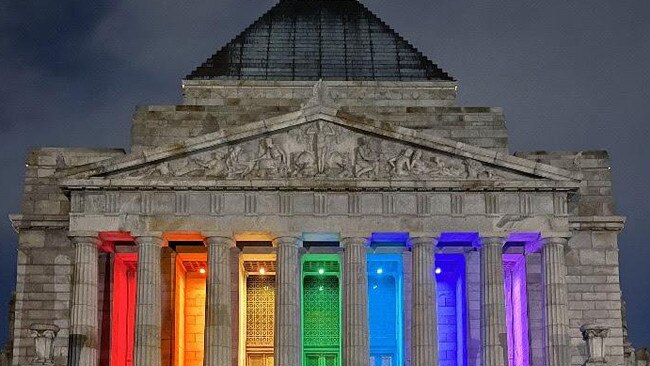

Its overt position came to mind this week in plans to bathe the Shrine in a political statement.

Almost everyone wants the best for LGBTI+ people. We loathe the idea of anyone being persecuted or derided for who they are. Yet many people who support LGBTI+ rights are offended by the idea of the Shrine in rainbow colours.

The Shrine is probably our most sacred church. It stands above political debate, a monument to sacrifice and loss.

When the Shrine is reduced to a billboard, a source of controversy, and a talking point, its timeless symbolism shrinks.

No one is saying that the Shrine people did not mean well. Certainly, pay homage to LGBTI+ interests in war, just as other commemorative bodies have saluted the service contributions of particular groups.

But emblazoning the monument in rainbow colours is a statement, not a sentiment; it compels a reaction.

The Shrine has never before been confused for a platform for debate. You have to either endorse the display or oppose it.

Sometimes, it’s not the message that offends, but its expression.

Melbourne City Council’s review of Australia Day services inspires a similar cringe.

Ian Hunter, who by virtue of race stands to supposedly benefit from the council’s position, probably said it best: “There’s just a few condescending people who want to make themselves look good to a minority.”

When was it decided that we needed self-ascribed agitators with little or no constituencies who assume aggressive stances on polarising talking points, on our behalf?

This patronising overreach is typically cloaked in a desire to eliminate offence.

Mostly, it reinforces offence.

When the Greens’ Adam Bandt recently claimed Aboriginal dispossession to justify putting the Australian flag in the corner, many of those he claimed to represent rejected his stand.

It wasn’t about them, much as the Australia Day review is not really about Melburnians or the ratepayers of the city. It seemed to be all about Adam Bandt.

He offered us a lesson. Controversial (or misplaced) gestures should be measured more for the motivations behind them than the causes they claim to represent.

The language of such choices is generally bathed in the rhetoric of inclusion and equality.

Those who oppose such gestures stand to be labelled as racist or homophobic or something equally as awful.

When Manly Sea Eagles players did not want to wear a gay pride jumper this week, they were instantly condemned as bigots, before the fuller story emerged. A gesture of supposed inclusion was in fact very exclusionary, given the players were confronted with a coercive demand.

They had been overlooked in the decision-making process. They were told to adhere to a political statement, and wear the jumpers, whether they wanted to or not.

Their religious beliefs challenge a sense of tolerance. The tone of some conservative rugby league stars raises questions of their suitability to public life. Yet the Manly players merited sympathy. They had been unfairly treated as performing political pawns.

Commentator James McPherson, writing in The Australian, explained it well: “(W) here’s the diversity and tolerance if everybody is forced to publicly support a particular point of view and zero dissent is permitted? That isn’t inclusion, it’s fanaticism.”

The problem, of course, is that most of us are not fanatics. And the fight against zealotry is fraught. It’s easier to silently disagree than engage when the public battlelines favour the shrill.

Grandstanding gestures tend to foster a silent resentment that sours the declared cause. Arguments for a shift of Australia Day’s date have bounced around for decades, yet advocating a shift, as framed by the Melbourne City Council review, fractures support for a date change.

Perhaps it is as simple as this: no one wants to be told – under the threat of shaming – how we ought to feel. That there is something defective or hateful in our thinking if we do not agree.

Stand by for more political statements sprinkled in Orwellian hues when equality seems to mean that the most outraged voices are more equal than others. Chances are the words will serve as cladding for darker forces, such as hypocrisy, division and great dollops of vanity.