Politicians have lost the art of making great speeches thanks to sound bites

THE importance of a powerful political speech has been lost on the modern generation of MPs obsessed by empty sound bites, writes Laurie Oakes.

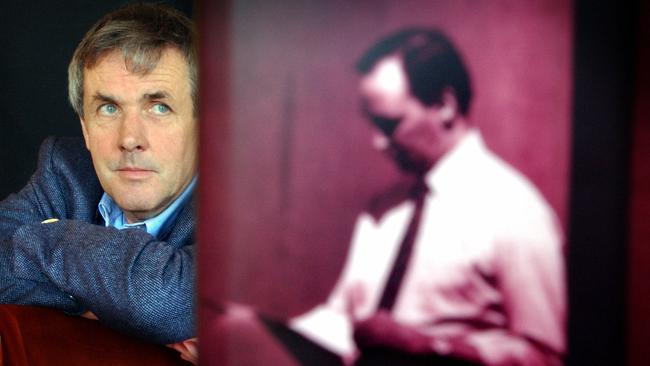

Laurie Oakes

Don't miss out on the headlines from Laurie Oakes. Followed categories will be added to My News.

LAST night in Sydney, the Labor Party turned on a tribute dinner for Graham Freudenberg, the greatest speechwriter this country has produced. A host of Labor heavies, past and present, were there to honour him. Ten days ago, leading conservatives gathered in Canberra to mark the 75th anniversary of Robert Menzies’ famous “Forgotten People” radio broadcast that set the course for the modern Liberal Party.

The twin events draw attention to a disturbing development. The kind of political speech that Freudy wrote or Menzies delivered is an endangered species.

There is the occasional sighting, of course. Kevin Rudd’s apology to the stolen generations, for example. Or Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech. But, for the most part, political rhetoric is pedestrian and stale. Originality in the discussion of ideas — for that matter, any departure from the tired party line — is seen as risky in a play-it-safe environment.

Sound bites take precedence over substance. Inspiration almost never gets a look in.

Part of the problem is the digital revolution and the non-stop news cycle it has produced. As former British prime minister Tony Blair’s speechwriter, Phillip Collins, wrote a few years ago: “Good political speeches are casualties of the sheer pace of modern politics.”

Freudenberg produced memorable and important speeches for a string of federal and state Labor leaders that included Arthur Calwell, Bob Hawke, Neville Wran and Bob Carr, but it was his collaboration with Gough Whitlam that was most remarkable. As Hawke said of the Whitlam-Freudenberg combination in his memoirs: “Graham became famous in Labor folklore for the symbiotic relationship which developed between leader and wordsmith.”

Freudenberg knew his employer so well and channelled him so perfectly that he not only ghosted speeches but was authorised to make statements in Whitlam’s name. Not surprisingly, Freudy is one of those most concerned about the declining importance of political speeches, telling The Australian’s Troy Bramston recently: “There are so many means of communication now that, tragically, speechmaking is taking a back seat.

“This is a tragedy, because the central art of politics is oratory.”

It doesn’t have to be this way. Good, well-written speeches could and should still play a central role in politics. Don Watson, who wrote for Paul Keating, set out some of the reasons in his book, Confessions of a Bleeding Heart. Noting that the speech retains a ritual function, he wrote: “It remains the principal means of flesh-to-flesh contact between the politician and the people; it is the best means of framing the philosophical dimensions of a policy; and it often provides an opportunity to set a new direction, create a new story, nail an opponent or massage one’s way out of a predicament.” A speech, according to Watson, is “a gesture towards order and respectability in a world which prizes spontaneity and tends towards chaos”.

The writing can be as important as the delivery because of the thinking and debate the process entails. Ronald Reagan’s key speechwriter, Peggy Noonan, said: “Speechwriting in the Reagan White House was where the philosophical, ideological and political tensions of the administration got worked out. Speechwriting was where the administration got invented every day.” That would not be happening in a White House where Donald Trump chooses to communicate with voters via Twitter.

TRUMP’S predecessor, Barack Obama, in contrast, believed in the persuasive power of a good speech. And he didn’t mind calling on the skills of gifted speechwriters, even though he was a brilliant orator in his own right. The chief White House speechwriter for Obama’s first term was Jon Favreau, still in his 20s. He understood the president so well that Obama called him a mind reader.

To work on Obama’s first inaugural address, Favreau took a laptop and headed to Starbucks for hours. Freudy’s fuel was beer, not coffee, and he dictated his speeches to a secretary in late-night sessions where he paced up and down leaving a trail of ash from the ever-present cigarette.

Menzies had no ghostly help with the Forbidden People speech. The use of speechwriters, though, has a long history. US Founding Fathers Alexander Hamilton and James Madison helped George Washington with his speechifying.

A member of Abraham Lincoln’s Cabinet provided him with a draft for his first Inaugural Address. The first White House speechwriter, one Judson P. Welliver, was appointed in 1921 with the impressive title of “literary clerk”. Margaret Thatcher’s famous “The lady’s not for turning” speech was written by playwright Ronald Millar.

And so on.

But there seem to be no new ghosts with Freudenbergian skills on the horizon. And few politicians with the interest or guts to make proper use of them if there were.

Laurie Oakes is the Nine Network political editor