Laurie Oakes final column: How TV killed the political stars

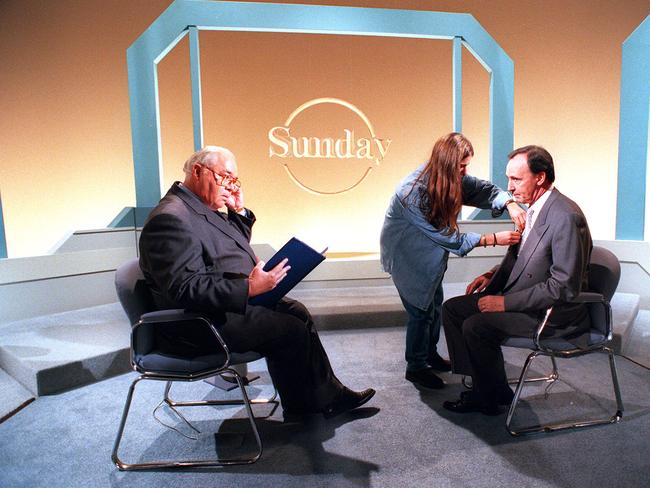

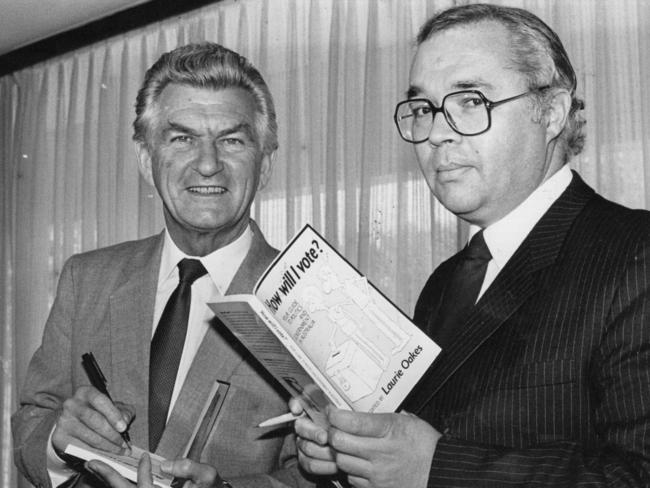

IN HIS final column, Laurie Oakes recounts our politicians’ ordeals under the television camera’s glare during his 48 years as a political reporter.

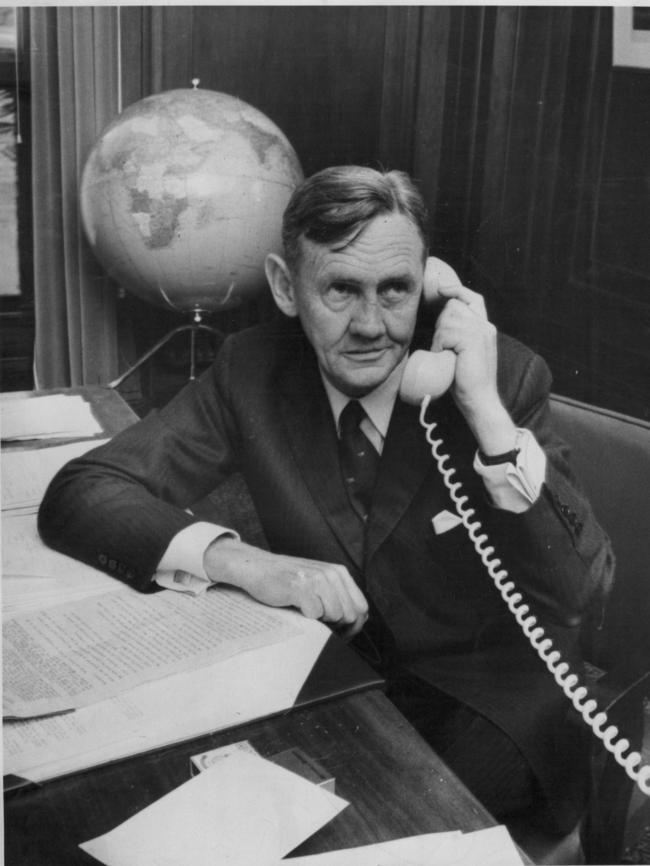

Laurie Oakes

Don't miss out on the headlines from Laurie Oakes. Followed categories will be added to My News.

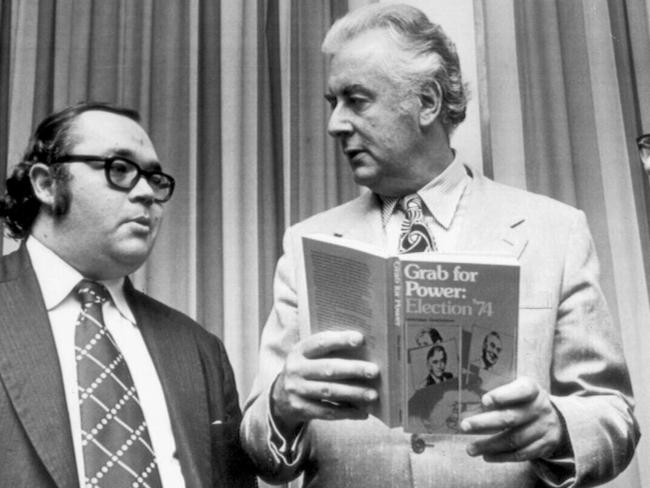

AS HE prepared for the 1972 election, Billy McMahon had a do-it-yourself television studio installed in his Sydney office.

It included a camera and video cassette machine, as well as a mock-up of the desk in the Prime Minister’s office in Canberra complete with a built-in autocue.

Billy would sit there for hours, delivering the speech, playing it back, seeking opinions from his wife and staff, then trying again — over and over.

At one point he complained that, if he couldn’t satisfy anyone, he might as well stick his head in a toilet bowl.

Despite all the practice, the result, when it went to air, was appalling. This newfangled TV thing was not McMahon’s forte. Neither was anything else, really, but that’s another story.

His opponent, Gough Whitlam, on the other hand, was a television natural. The Whitlam policy speech, delivered to a packed civic hall in Blacktown and supported by a galaxy of stars singing Labor’s clever “It’s Time” jingle, got rave reviews.

The 1972 election was our first television campaign and, I believe, marked the point at which TV became central to Australian politics and changed it completely. Why does that matter?

Because, as I retire after more than 48 years reporting federal politics in Canberra, I’ve been thinking about why politicians and the political process are in such bad odour.

Congratulations @Laurieoakes. Beholden to none. An awesome force in journalism. With an excellent sense of humour.

— Annabel Crabb (@annabelcrabb) August 3, 2017

The latest evidence, if more were needed, was marginal seat focus group research in Fairfax newspapers this week showing a disillusioned, disheartened and cynical electorate that sees politicians as out of touch and out for themselves.

There are lots of contributing factors, of course, but I reckon television, and the way politicians have responded to it, is one of the key ones.

Also important is digital technology and the high speed news cycle it has given us.

And there is the way pollies have distanced themselves from the punters, in part because of TV and other technological developments, increasing the likelihood that they do become out of touch.

I’ve been mulling this over because I don’t believe that politicians as a species have changed much since I first walked into Canberra’s old Parliament House in January, 1969.

LAURIE OAKES’ GREATEST MOMENTS

After 50 years as a journalist @LaurieOakes is retiring. From everyone at the Walkleys, thank you for all you've done. We wish you the best. pic.twitter.com/O7QjlO3IGc

— Walkley Foundation (@walkleys) August 3, 2017

Almost all the MPs and Senators I have known, no matter what their party affiliation or when they were elected, were well-intentioned when they first took their seats, determined to change things for the better for their constituents and the country.

But politicians are forced to compromise their principles and disguise their true beliefs by the requirements of the democratic system. It’s the nature of the beast.

There’s a piece of American verse called “Democracy Unveiled”, written more than 200 years ago and which I came across early in my career as a political journalist, that sums up the problem.

And I’ll unmask the democrat,

Your sometimes this thing, sometimes that,

Whose life is one dishonest shuffle,

Lest he perchance the mob should ruffle.

I recall it when I see in opinion polls the alarming statistic that only about half of Australians aged between 18 and 29 think democracy is preferable to any other form of government.

Despite the doubts of young voters, democracy is certainly the best system available, but it has shortcomings. One of them is that, in trying not to ruffle the mob or ruffle their party colleagues, politicians almost inevitably come to seem insincere, hypocritical, inauthentic, even weak. The dishonest shufflers of the poem.

Television has magnified this.

TV is a great tool for politicians to get their messages to voters. The other side of the coin, though, is that it gives voters a closer and more constant view of pollies and how they operate.

Because voters can see politicians delivering their lines, and see it in close-up, they can pretty much tell when lies are being told.

Voters are not mugs and have learned to spot the tricks politicians use — evasions, scripted talking points, giving answers unrelated to questions asked.

Those tricks, honed in media training courses as politicians became more risk averse in the television age, have gradually become counter-productive thanks to television.

He's broken some of the biggest political stories of our time, but now @LaurieOakes is finally calling it a day. #9News pic.twitter.com/0MvlzACJhY

— Nine News Queensland (@9NewsQueensland) August 3, 2017

It is glaringly obvious to almost everybody now that a bit of straight talking works much better on TV than pollie-speak and dishonest shuffling, but it’s taking politicians and their minders a long while to adjust.

Television also magnifies the aggression and bad behaviour of politicians.

Televising of Parliament was delayed by a couple of years, even though $50 million had been spent wiring the new Parliament House for that very purpose, because the then Labor Government was worried about viewer reaction to Paul Keating calling opponents “sleazebags”, “scumbags” and “you stupid foul-mouthed grub”.

The concerns were not misplaced.

But Whitlam had been every bit as vicious as Keating, possibly more so, calling Sir Garfield Barwick ”a bumptious bastard”, referring to Billy Wentworth’s “hereditary streak of insanity”, and commenting on the “bloated and porcine appearance” of a couple of Labor renegades.

He even called McMahon a “quean” in Parliament — and then checked that Hansard spelt it correctly.

The only difference is that Whitlam was not on camera, Keating was.

While we’re on the subject of aggression in politics, there seems to be an impression that the knifing of prime ministers is something new.

Sure, the back-to-back nature of the Julia Gillard v. Kevin Rudd drama and the continuing saga of Malcolm Turnbull v. Tony Abbott is unusual. But the political assassination of John Gorton in 1971 was every bit as brutal.

A bombshell only @LaurieOakes could break. Fearless and peerless for five decades. There will only ever be one Laurie Oakes.

— Bill Shorten (@billshortenmp) August 3, 2017

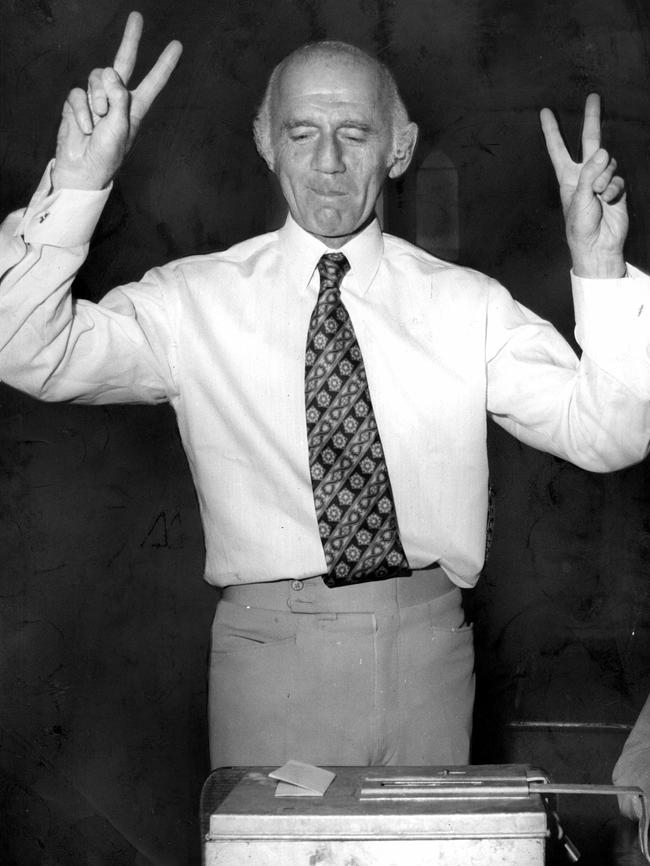

Gorton was ruthlessly undermined by those — including media mogul Sir Frank Packer — who wanted McMahon in The Lodge.

Sir Paul Hasluck, one of McMahon’s ministerial colleagues, who became Governor-General, wrote of him: “Disloyal, devious, dishonest, untrustworthy, petty, cowardly — all these adjectives have been weighed by me and I could not in truth modify or reduce any one of them in its application to him.”

McMahon once tried to steal a tape recorder from me. He borrowed it, then refused to return it, claiming: “It’s mine.” I had to walk into his office uninvited, grab the device from his desk and point to where the name of the radio station I worked for was engraved.

McMahon was a liar and a sneak, prone to such utterances as: “We will honour all the problems we have made.” That he became prime minister was a disgrace.

What was more ridiculous, though, was that the Liberals — presumably out of guilt — elected Gorton as his deputy. The forces backing McMahon then had to assassinate Gorton a second time.

MALCOLM FARR: WE MAY NOT SEE THE LIKES OF LAURIE OAKES AGAIN

.@LaurieOakes, you managed to leak every big story except this one. Good on you mate, you were undoubtedly one of the best.

— Barnaby Joyce (@Barnaby_Joyce) August 3, 2017

Before television took over politics, politicians used to go to the voters. They had no choice.

They would talk to voters from the backs of trucks. They would visit factories and other workplaces and actually listen to the employees, not just provide picture opportunities in hi-vis vests as happens today.

And they would hold public meetings that were genuinely that — not the tightly controlled, invitation-only affairs we have got used to in more recent years.

Television enabled politicians to reach voters without going near them, so — increasingly — they cut themselves off. Now they are paying the price.

They also isolated themselves from ordinary mortals with the move to a new Parliament House in 1988.

The old House was intimate, with a central hall that everyone had to pass through. Politicians, staffers, bureaucrats, journalists and members of the public, all thrust together.

A tourist from Perth could grab the ear of the prime minister. No-one would prevent it.

But the new building was strictly compartmentalised so that MPs and the public rarely mixed. And now heavy security adds to that separation and isolation.

This is my final column. To my readers, thank you and goodbye.