Why escaped convict William Buckley was welcomed as family into Aboriginal clan and stayed 32 years

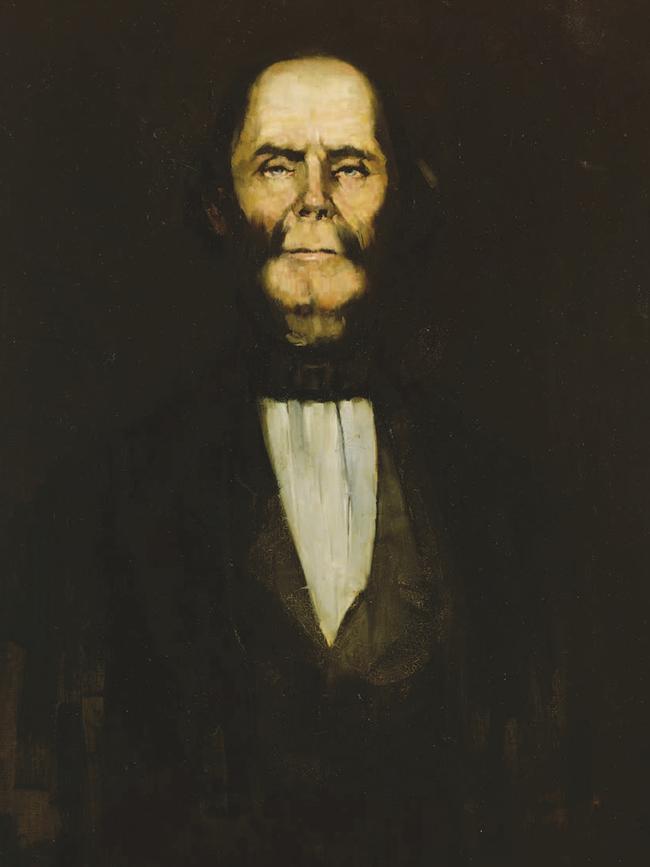

A momentary decision to steal a spear from a warrior’s grave was the life-changing quirk of fate that led escaped convict William Buckley to spend 32 years living with an Aboriginal clan.

Black and White

Don't miss out on the headlines from Black and White. Followed categories will be added to My News.

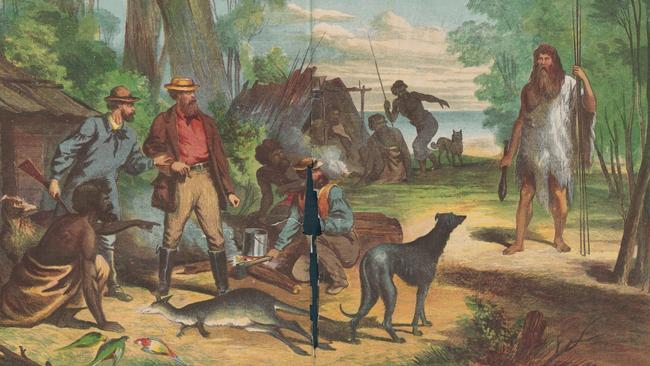

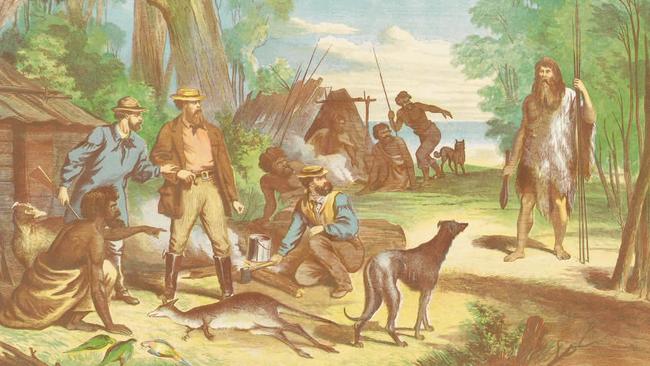

When escaped convict William Buckley was found on the Bellarine Peninsula by the Wadawurrung clan in 1804, they thought he was one of their own returned from the dead.

Convinced he was their departed relative – a great warrior – they gave him a hero’s welcome and took him in.

For almost 32 years, Buckley lived as a Wadawurrung man, learning the language, culture and survival skills of his adoptive clan.

Buckley is the subject of the latest episode of the free In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters, available today.

His incredible tale is told in a new book called The Ghost & the Bounty Hunter by Adam Courtenay, the son of the late great Bryce Courtenay, one of Australia’s best-known novelists.

Adam Courtenay says many indigenous clans then believed the white people they saw - mostly whalers and sealers - were their own kin returned from the dead.

“The Aboriginal people of Victoria believed that when you died, you went over to Tasmania, believe it or not, and when your spirit came back, you came back as a white person,” Courtenay says.

He says that belief stemmed from their observation that after a person died, the body would become whiter.

“So they didn’t quite know if these people were returned ghosts,” Courtenay says.

“If they were recognised as former kin come back and returned, they were treated extremely well.”

Courtenay says the clan concluded Buckley was one of their kin - a great warrior who had been killed - because of one simple life-changing decision he made earlier.

Buckley had removed a distinctive spear from a gravesite around present-day Torquay.

When the clan saw Buckley carrying that spear, they concluded he was the original owner, their dead kinsman.

“He knew he was desecrating the grave, but he thought maybe the spear could help him hunt or something. He could use it as a walking stick,” Courtenay says.

“They saw him with this spear, and they believed he was a recently departed relative of this tribe.”

Buckley, or Murrangurk as he became known, was feted as a hero and greeted with a “reverse wake”.

“They went nuts. They were so crazy that he’d come back to them, so soon actually. They’re wailing and screaming because this person they love very much has come back to them,” Courtenay says.

Initially, Buckley was terrified and reluctant to go with the clan.

At the time, white settlers believed the indigenous people were cannibals.

“Buckley, of course, is going, ‘What the hell?’” Courtenay says.

“He couldn’t speak the language at this point. He got the idea that he was being really feted. But he still seemed to think he was going to be eaten next day.”

But Buckley was embraced by the clan and lived with them for almost 32 years, until he walked into a campsite of John Batman’s men in 1835, the year Melbourne was founded.

Listen to Part 1 of the podcast today, and tune in for Part 2 next Monday when we will hear about Buckley’s life with the clan and role in the formation of early Melbourne.

Play the free In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters on iTunes here or Spotify here or on your favourite platform.

Listen to previous episodes including the tale of Australia’s lost convict boys, how “last Tasmanian” Truganini became an outlaw on the run in Victoria after a double murder, and the link between the Ashes urn and Ned Kelly armour.

The Ghost & the Bounty Hunter (HarperCollins, RRP $29.99) is available now.

Read an extract from the book here.

And check out In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper Monday to Friday to see more stories from Victoria’s past.