Is the Kelly Gang republic is more fact than fanciful myth?

Was outlaw Ned Kelly vying to be the president of a Victorian republic or is this fanciful myth? This critic thinks otherwise.

In Black and White

Don't miss out on the headlines from In Black and White. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Did Ned Kelly plan to be president of a Victorian republic?

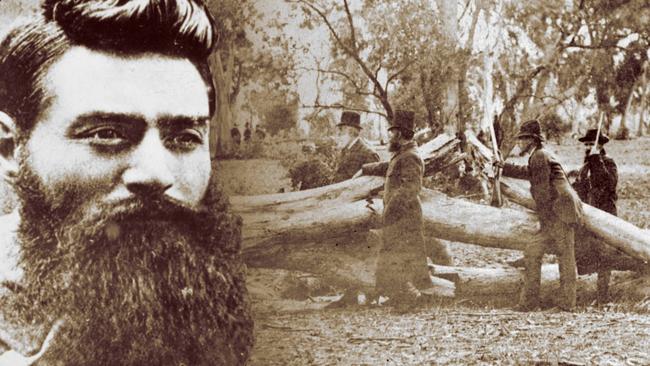

It is perhaps the most intriguing forgotten piece of the Ned Kelly story — the claim that the notorious outlaw wanted to declare a huge chunk of Victoria a republic, put the capital in Benalla and declare himself president.

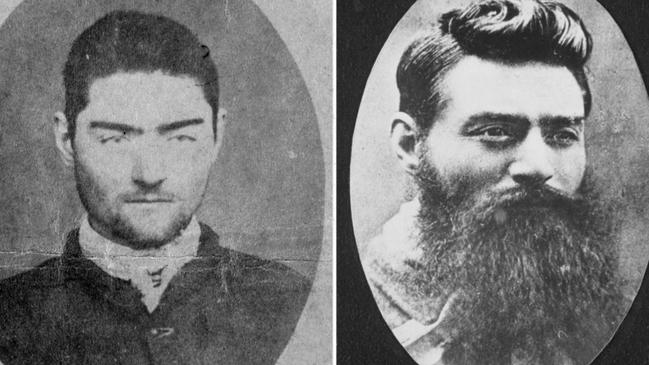

The brief and violent life of Australia’s most famous bushranger ended in November 1880 when he was hanged at Melbourne Gaol, but he has since lived on in popular folklore.

His iconic armour and rebellious attitude has become entrenched in the Victorian psyche.

But would this ruffian, a hero to some and a villain to others, have made a decent president?

According to some, Kelly intended to use an act of terrorism against the police to take over a huge part of north eastern Victoria, declare it a sovereign state and make himself the leader.

While some historians and researchers dismiss the idea as fanciful myth, others say it’s totally real and point to evidence of a founding Kelly Republic document.

One night in Glenrowan

Ned Kelly’s life as an outlaw ended at Glenrowan where a shootout with police at a small hotel ended the life of his fellow gang members, including his teenage brother Dan.

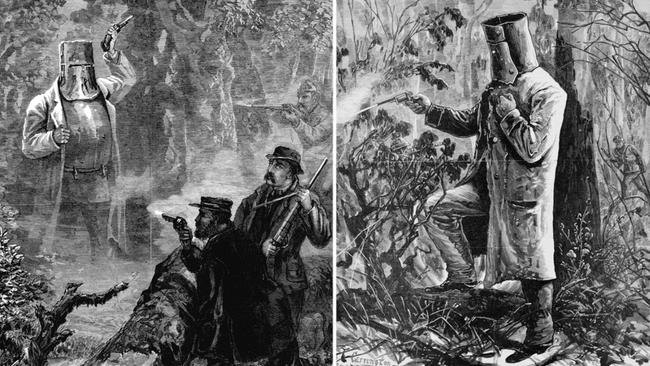

Ned himself, clad in iron and determined to go down fighting, lasted through the night before his final stand, and was captured with serious bullet wounds to his legs.

As his captors stripped off his metal shell, the bushranger was found to be wearing a green sash awarded to Ned in childhood for saving another boy from drowning.

It is also at this point the theory of the Kelly Republic begins.

It was claimed that Ned was also carrying a document in his clothing during his last stand that outlined plans for a sovereign state in north eastern Victoria, with a central capital in the township of Benalla, and with Kelly himself as the president.

Ned had planned to kick off a sort of revolution by derailing a specially scheduled train that was due to arrive at Glenrowan carrying police officers, trackers and a few members of the press.

But the plan had apparently gone badly wrong, leading to the fatal siege at the hotel.

The story about the republican document was reported as fact in Australian newspapers at least as early as 1900, was repeated in the Irish Times in 1920, and in various Australian articles of the 1940s.

But the document itself was awkwardly missing.

That was explained away by the idea that colonial authorities in Melbourne suppressed the document because it could spark treasonous sentiment among the Kelly Gang’s sympathisers.

It was believed the Kelly Gang had a legion of supporters in the bush, with theories that a small army of rebels was waiting to aid Ned in the hills near Glenrowan, but failed to rally when the train derailment didn’t come off.

The Kelly Gang’s true intent, and the real events that led up to the Glenrowan siege, have been the subject of debate since they occurred.

Without proof of the document, the republic theory remained likewise shrouded in mystery.

Researchers sympathetic to the republic story relied on passages in Ned Kelly’s lengthy Jerilderie letter, a sort of outlaw manifesto in which he used strong pro-Irish and anti-English sentiment.

In the 8000-word letter, which Kelly tried to get published as a pamphlet when he and his gang held up the NSW town of Jerilderie, he warned that people who don’t like the Kellys should leave Victoria, and ended with the almost dictatorial statement, “I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warning but I am a Widow’s Son, outlawed and my orders must be obeyed.”

A new lead

Then in 1962 came an explosive story from Melbourne theatre critic Leonard Radic.

Visiting the UK, he claimed to have seen a document written by Kelly outlining his plans for the north eastern republic, on in the Public Records Office in London.

Talking to the Sunday Herald Sun in 1995, Radic said:

“When I saw the document it was in a glass cabinet. It looked like a handbill that you would see pasted on a lamp post and it was old fashioned, 19th-century type.

“I don’t remember the exact wording, but it talked about the setting up of an independent Republic of northeast Victoria.

“I went home and told my wife about it because her family came from the Greta district, as the Kelly’s did.”

When he later told Kelly researchers and enthusiasts what he had seen, a huge search was made through the British archives for the golden puzzle piece that could prove once and for all the Kelly Republic theory.

Alas, nothing could be found. The document had gone missing again.

This led some to question the reliability of Leonard Radic’s story, but there were whispers that the document might have been on loan from a private collector who wanted to remain anonymous.

Radic found an ally in former Victorian chief justice John Harber Phillips AC who, in a speech in 2003, claimed that Radic’s testimony ought to be taken seriously, and was evidence the republican document actually existed.

How the document would then fall through the cracks of archive bureaucracy was not explained.

Just as Kelly’s status as either a virtuous hero or a bloodthirsty criminal will never be settled, perhaps the question of the Kelly Republic will never be definitively answered.