How ‘hero’ Ned Kelly and his giggling younger brother hunted a lawmen to his death

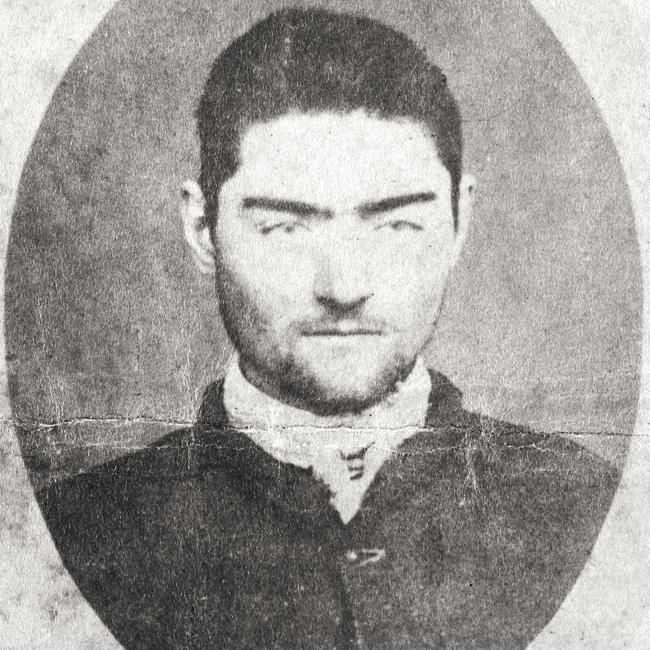

Ned Kelly’s legend as a folk hero is torn down by a new account of how he and his “grotesque” brother mercilessly murdered three men – hunting one down like a wounded animal.

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Ned Kelly’s stand against authority is part of Australian folklore, seen by some as heroic.

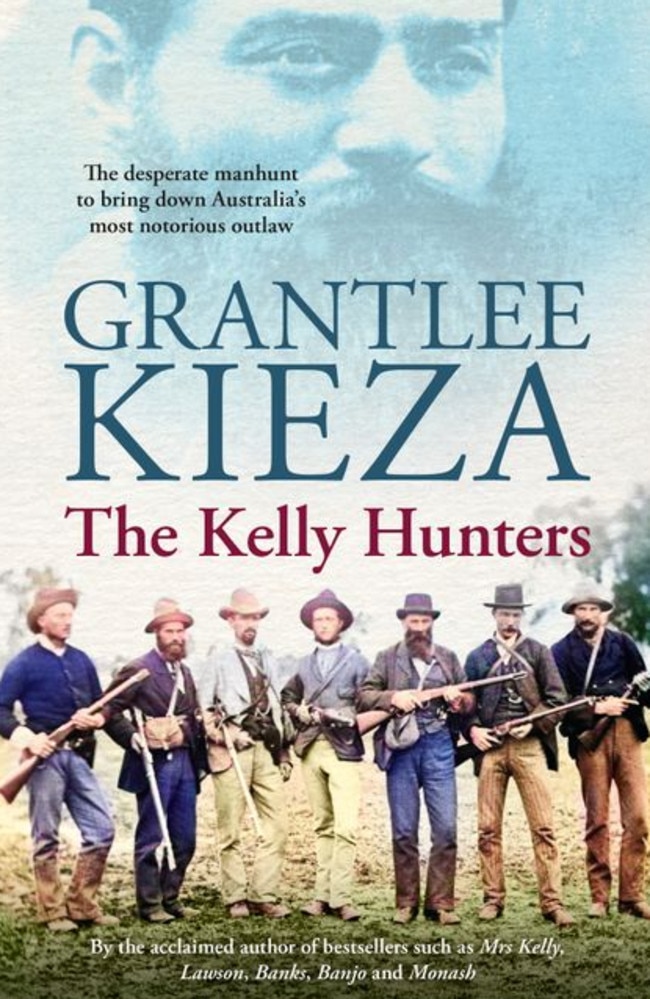

GRANTLEE KIEZA’s new book The Kelly Hunters examines that story from the other side – that of the ordinary lawmen tasked with tracking him down while senior officers’ egos ran wild. This edited extract details the 1878 incident that changed it all, as Kelly turned from a wanted thug into a cop-killer.

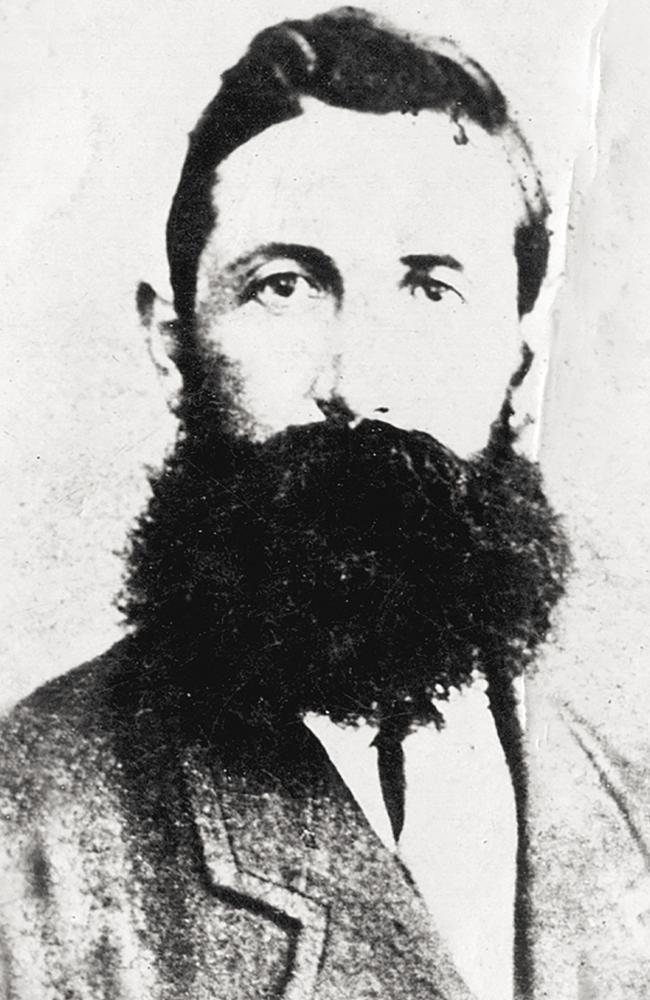

After a breakfast of salted meat and bread in the secluded bush beside Stringybark Creek in the Wombat Ranges, Sergeant Michael Kennedy decided that he and Constable Michael Scanlan would scout out the surrounding area for the outlaw Ned Kelly and his gang while constables Thomas McIntyre and Thomas Lonigan would remain at the camp.

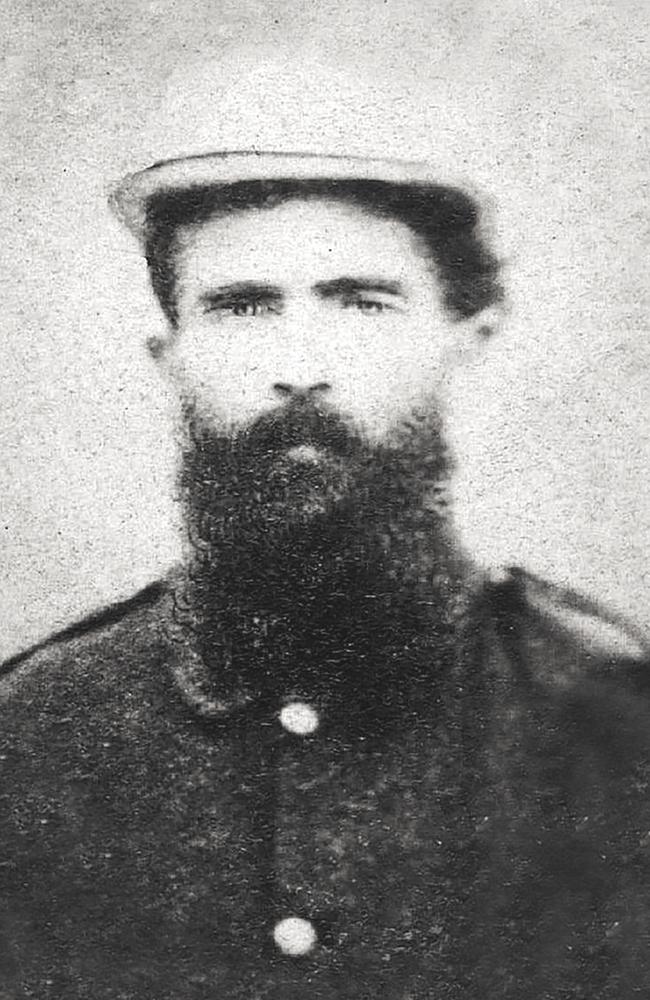

McIntyre baked some soda bread while Lonigan tended to the horses and read a pamphlet of Argus articles called ‘The Vagabond Papers’ in which the eccentric middle-aged highwayman Harry Power was interviewed and described the teenage Kelly as a coward and a traitor who had betrayed him. Meanwhile, less than one kilometre away at their hideout at Bullock Creek, Kelly and his men dressed in the colours of the Greta Mob (his bushranger gang), with red sashes around their waist. They put the chin straps of their low, flat hats under their noses.

At about noon, McIntyre was still busy baking his bread when Lonigan, lying down and reading about the young and unpredictable Ned Kelly, called out that he heard a strange noise down the creek. McIntyre hadn’t heard anything but, suspecting it might be a kangaroo or wombat for his cooking pot, grabbed a shotgun and went to investigate.

He found magnificent lorikeets, rosellas and sulphur-crested cockatoos and shot two birds for dinner.

At 5pm, with the sun starting to sink, McIntyre began to build a large bonfire at the intersection of two fallen logs. He wanted to guide Kennedy and Scanlan home in case they were hand-carting wood.

From a thicket of tall speargrass, four sets of fierce eyes watched their every move.

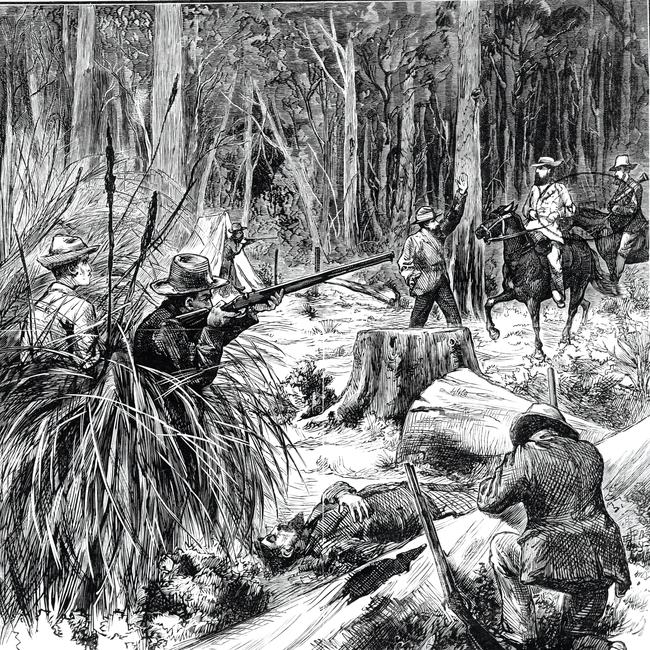

‘We could have shot those men without speaking,’ Kelly claimed later, ‘but not wishing to take life, we waited.’ McIntyre laid a shotgun against a stump and Lonigan sat on a log. He had been strangely silent, troubled and lost in thought all day, and he gazed intently into the fire. McIntyre was boiling the billy, with his face to the blaze and his back to the speargrass, when he heard four voices crying out: ‘Bail up, hold up your hands!’ At first, he thought it was Kennedy and Scanlan playing a trick, but as he turned, he saw four young men advancing in a line from the thick grass. They all had guns.

McIntyre immediately recognised the biggest one on the right as Kelly, and he threw his arms out horizontally. Lonigan, though, made a run for cover behind a log and reached for the clasp on his holster.

He had taken only a few steps when Ned and his mates unloaded. Lonigan exclaimed, ‘Christ I am shot,’ and then Ned pumped a .577 slug bullet down the wonky barrel of his old carbine and straight through Lonigan’s right eyeball. Lonigan fell flat, his legs and arms extended, his head thrown back and his chest heaving.

McIntyre was so stunned he dropped his hands, and Kelly charged at him. Kelly tossed the carbine into his left hand, then reached behind his back, pulled out a revolver with his right and roared: ‘Keep your hands up. Keep them up.’

McIntyre did as he was told.

All the time Lonigan was struggling on the grass, ‘plunging on the ground very heavily’ but after thirty seconds or so he ceased to breathe.

McIntyre shut his eyes and said softly, ‘Oh God, my time has come.’ Standing there in his shirtsleeves and a black oilskin cap, he trembled as Kelly and the others pointed their weapons at his chest.

McIntyre’s recall of what happened in those chaotic, mad moments would be shaken by his trauma, but it would remain consistent over time.

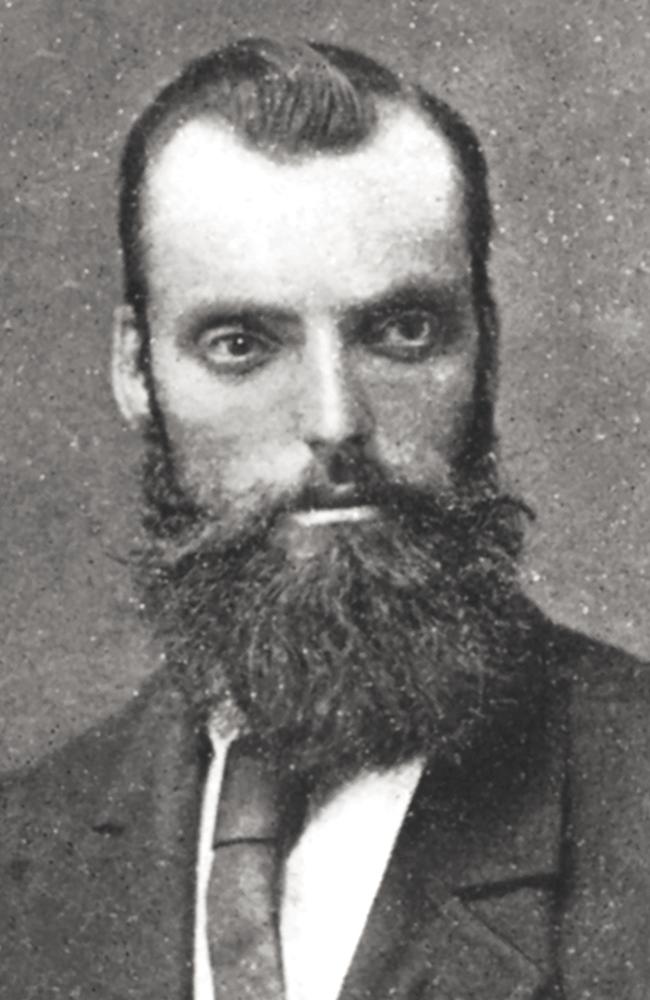

Ned’s brother, Dan, the youngest of the gang at just 17, was nervously excited by the whole business and was giggling, almost hysterically. McIntyre thought there was something ‘grotesque’ about the youngster’s appearance. Kelly told McIntyre to lift his hands high above his head while he frisked him. Then he jumped over the log to Lonigan’s corpse and took his Webley revolver. ‘Dear, oh, dear! What made that bugger run?’ Ned had just realised the enormity of his crime and his downcast expression made McIntyre think that ‘he may not have contemplated murder in the first instance, relying on taking us separately and unprepared’. McIntyre now feared there would be a massacre to cover up the crime.

McIntyre tried not to look at Lonigan’s lifeless, bloodied face lying nearby, but he couldn’t help glancing at his comrade as the sun began to set behind the trees all around them.

As night approached, Kelly armed himself with two rifles and a revolver and told his men to take their places as he hid behind a log. Steve Hart remained in the policemen’s tent, and Joe Byrne and Dan Kelly secreted themselves in speargrass. Kelly told McIntyre to stand near him and he asked him about the other police on their way back.

McIntyre said Kennedy was a good man with a large family and that Scanlan was good-natured and inoffensive. Kelly said he would not kill them if they surrendered and that he could already have shot McIntyre if he had wanted to. He would have no qualms, he said, about shooting and roasting Fitzpatrick, Flood, Strahan or Steele – police officers against whom he bore a murderous grudge.

Kelly asked him how Kennedy and Scanlan were armed. ‘Very meagrely.’

‘What do you mean? Have they got revolvers?’

‘Yes.’

‘Have they got a rifle?’

McIntyre hesitated.

‘Tell the truth, you bugger,’ Kelly snarled, ‘or I swear I will put a hole through you.’

‘Yes, they have a rifle.’

‘A breech-loader?’

‘Yes.’

‘You did come to shoot me! I think you planned to riddle me with bullets?’

‘No, to arrest you. We are not sent out to shoot people, we are just sent out to do a certain duty. You cannot blame us for what Constable Fitzpatrick has done to you,’ McIntyre said.

‘No, but I swore after letting him go that I would never let another go, and if I let you go now you will have to leave the police force.’

McIntyre would say anything to save his skin.

‘I will. I will leave the police force. My health has been bad anyway, and I have been thinking of going home for some time.’

‘Good, see that you do,’ Ned snarled.

‘If I got these other two men to surrender, what will you do with us?’

‘Well, you had better get them to surrender, because if they don’t surrender, or they get away, we will shoot you. But we don’t want their lives; we only want their horses and firearms.’

Ned had his revolver in his waistband and two rifles resting against the log. McIntyre eyed them, thinking to himself that if Kennedy and Scanlan showed up he might be able to take advantage of the surprise and take one of the rifles with ‘a sudden spring’.

Steve Hart was watching McIntyre from the tent, though, and sensed his thinking.

‘Ned, look out,’ he cried, ‘or that bugger will be on top of you.’

Kelly seemed unconcerned. ‘If you try anything,’ he said, ‘you will soon find your match, for you know there are not three men in the police force a match for me.’

McIntyre believed that Kelly for all his big talk was a ‘lazy blackguard’ who would rather steal than put his muscularity to work for good wages.

But he kept his opinion to himself.

Suddenly, Kelly heard horses approaching from the north.

Sergeant Kennedy’s gold watch told him it was approaching 6pm as he and Scanlan made their way through the dense forest back towards what they expected would be McIntyre’s warm supper.

Kelly whispered to McIntyre to sit on the log and do exactly as he said – exactly – or he would be killed.

Kennedy was about 45 metres away, riding towards the camp with Scanlan 10 metres behind.

When Kennedy was within 6 metres of McIntyre, the constable stammered: ‘Ssss ser-ser-ser-geant, you had better surrender; you are surrounded.’

Then Kelly bellowed out: ‘Bail up.’

Kennedy thought it was McIntyre and Lonigan playing a gag, and as Scanlan started to dismount, the Spencer rifle strapped over his shoulder, Kennedy playfully moved his hand towards the revolver in his side holster.

But a shudder roared through him as Kelly fired a warning shot over the sergeant’s head and his three accomplices roared: ‘Bail up, throw up your hands.’

Scanlan, about 25 metres from Kelly, tried to unsling the Spencer, but the shooting frightened his horse and it reared. Three or four shots were fired at the same time. Scanlan was hit under the right arm and fell off his horse and landed on his knees. He struggled up but fell again as blood stained his coat.

Kennedy ducked down, using his horse’s neck as a shield, and shoulder.

But the sergeant dropped his revolver in the commotion. His riderless horse reared with the noise of gunfire and McIntyre, suspecting Kennedy had been killed, leapt onto the mare’s back, held on for dear life and, without his spurs, booted her flanks into a gallop. Shots rang out behind him as Dan Kelly cried, ‘Shoot the bugger, shoot the bugger.’

Kennedy fumbled to regain his revolver and started firing back. He ducked behind trees, trying to escape in the direction of Kelly’s fortress on Bullock Creek. Ned grabbed the Spencer from Scanlan’s now-lifeless hand, but he didn’t know how to work the lever action and tossed it aside to hunt Kennedy with his shotgun. Kennedy broke open his Webley and reloaded it with six more bullets, but his pursuers were close behind and they had rifles with much greater range.

According to Kelly’s account, Kennedy kept firing while his four attackers sheltered behind trees. He took cool and deliberate aim as he fired five more shots. One of his bullets passed through Kelly’s whiskers, and another through his sleeve. Then Kennedy started running again with the Kelly brothers on his heels.

Kennedy ran for about half a mile. He then hid behind a tree and fired the sixth and final bullet in the Webley. As Kelly saw him levelling the revolver at his head, he dropped to his knees just as the bullet whizzed over him, and he then shot Kennedy in his right side. The sergeant fell, wounded and helpless, at the foot of the tree.

Kelly said that they interrogated the dying man for two hours about how many other police were coming for them, how they were armed, and whether Kennedy had come to kill him.

All Kennedy wanted to talk about was Bridget and his children. He told Kelly that he had five little ones and that Bridget would soon be having another baby.

Kelly told Dan to get some water from the creek for Kennedy’s parched lips and he later said that Kennedy, knowing he was dying, scratched some lines of affection for his wife on three slips of paper he had in his pocket. He asked Kelly to give the letter to Bridget, but Kelly never did.

Kelly knew that McIntyre would likely soon sound an alarm and that out here Kennedy would soon be at the mercy of ants, flies and dingoes.

No one thought about getting help for Kennedy. Instead, Kelly put the muzzle of his shotgun to within a few inches of Kennedy’s chest.

‘Let me alone, for God’s sake,’ Kennedy mumbled, ‘let me live, if I can, for the sake of my poor wife and family; surely you have shed enough blood already.’

As Sergeant Kennedy fretted about how his wife and children would survive without him, Ned Kelly blew a huge hole in his chest.

This is an edited extract from The Kelly Hunters by Grantlee Kieza, published by ABC Books on March 16 and available for pre-order now from Booktopia.

Originally published as How ‘hero’ Ned Kelly and his giggling younger brother hunted a lawmen to his death