Andrew Rule: The Melbourne cop who still splits opinion

Wayne Strawhorn is a former cop who did serious jail time after a long trial. But “the jury” of public opinion is still out on whether he deserved it, or was a victim of vicious police politics in a force being cleansed of its “old school” ways, writes Andrew Rule.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Wayne Strawhorn didn’t look worried about appearing at the royal commission into police informers early in the week. Compared with standing trial and staring down jail time, a guest appearance at this lawyers’ benefit picnic is a walk in the park.

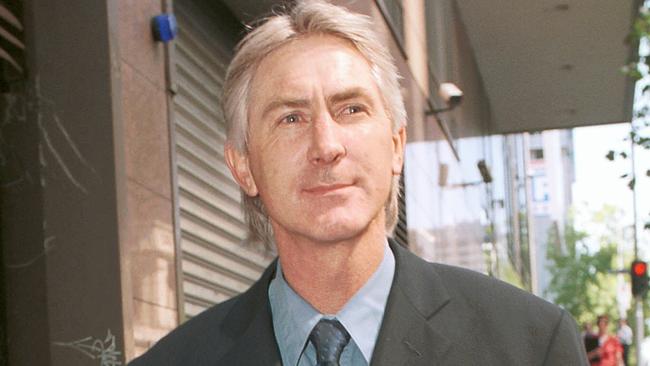

The former country footballer, ace drug squad detective and model prisoner has led a quiet life since getting out of jail nine years ago, but he still has a lean and hungry look, more hunter than hunted.

Fit, silent and alert at 64, he cuts a wiry figure in the hearing room full of well-fed barristers: a greyhound surrounded by labradors and the odd poodle.

READ MORE FROM RULE:

WHY DO SMART WOMEN FALL FOR CROOKS?

THE DAY I HEARD A MAN SHOT DEAD

HOW MOKBEL WAS IN SHARK TANK WITHOUT A CAGE

Weathered hands and wrists poke from the grey suit worn above well-polished black boots. The blue shirt is open at the neck — the missing tie a reminder he doesn’t have to wear the detective’s unofficial uniform any more.

But when the old pro takes the stand there’s no sign of nerves as he rolls out the oath, bible held high. He’s all business, eyes still and voice steady, rattling off crisp, precise answers just the way he did when he put some of the country’s biggest drug traffickers behind bars — notably the industrial-scale criminal John William Samuel Higgs, who ran drugs coast to coast.

The Higgs triumph was, of course, before Strawhorn’s world caved in. Some of his fellow police testified he had illicitly sold large amounts of precursor drugs to drug traffickers — specifically, two kilos of pseudoephedrine to the late Mark Moran — and supposedly pocketed chunks of cash.

The case dragged on, much to the anguish of Strawhorn’s two sons and daughter, the ones he’d brought up alone after his wife’s illness and death.

A jury finally convicted Strawhorn (and he was sentenced to a maximum seven years) in 2006.

But “the jury” of public opinion is still out on whether he really deserved it … or was a victim of vicious internal politics in a police force being cleansed of its “old school” ways by “new broom” bosses.

When Strawhorn was first charged in 2003, police and the odd comedian gathered at the Rochester Hotel in Fitzroy, then run by a former drug squad member who had done many undercover “jobs” for his favourite boss.

They raised, says one attendee, “a few grand” to put towards his defence. Who put in what amounts of cash is anyone’s guess.

Once the cell door closed, most police tended to be discreet about public displays of support towards him. But at least one staunch serving detective and several former officers visited him in prison. And some seasoned reporters also sympathised with him and still do.

Strawhorn’s supporters say he was a brilliant street copper but too careless about the meticulous record-keeping that would be vital to document his “controlled” police operation to trap crime gangs by selling them precursor drugs.

One old friend of Strawhorn’s says he warned him repeatedly that he was leaving himself open to be scapegoated for breaches committed by others. Strawhorn’s biggest fault, say his friends, was his “She’ll be right” attitude about record keeping.

A former detective now working as a private investigator recalls “a positive relationship” with a man whose reputation was as impressive “as anyone in the force”.

And respected former chief racing steward Des Gleeson recalls Strawhorn as a trusted and valued member of the racing squad, a moderate man who volunteered to be “designated driver” at country racing carnivals. Gleeson was shocked by his downfall.

There is another point of view. Maverick lawyer Andrew Fraser — targeted by Strawhorn and jailed on cocaine charges — swears his adversary was always “bent” and ruthless.

As a confidante of the Moran crime family, Fraser was in a position to know. Fraser’s view was ultimately shared by some in the police hierarchy keen to be seen as cleaning up a drug squad rumoured to be “running hot”.

The truth? The answer, as they say, is a pineapple. But it is clear from talking to Strawhorn’s former colleagues that he was a hangover from the “old school”, where police tended to be unaccountable as long as they got results.

The implication is that times changed but he didn’t.

A jury never gets to hear everything about an accused’s character or behaviour. But “witnesses” who were never called to testify in Strawhorn’s trial (and who wouldn’t say much in any case) privately reveal things that might perplex Strawhorn’s biggest boosters, people who rely on the line: “If he was corrupt and copped money from drug deals and drug dealers, where did he spend it? Where are the big boats, the flash cars, the holiday houses and first-class air tickets to Disneyland?”

It’s a fair question. But the fact there’s no brazen and ostentatious spending doesn’t mean there was no spending at all. The prosecution case is that he was smart enough to cover his tracks.

Some bent cops, perhaps, financed family members or friends as “fronts” in properties or other big purchases. But it seems Strawhorn was a model of financial discretion. He didn’t buy flashy things or properties that would require compromising documentation.

Instead, suggest those who knew him, the one-time country boy from Numurkah used his nimble brain to study art and wine … and bought excellent examples of both as an investment.

Buying real estate would be a red flag without an elaborate cover-up that would require involving others. But adding value to an existing property? That’s different.

Which might be why the big, brick period house near Caulfield racecourse that Strawhorn has owned for a long time has gradually been turned into a showpiece.

The “tradies” have come and gone over more than 20 years and the word is that most have been paid in cash.

One bemused contractor still tells friends he will never forget the day the quiet, polite detective slipped him about “twenty grand” in “folding money” back in the 1990s. It’s a question that will never be asked in court, of course.

But if it were put, the next question might be about Strawhorn’s favourite hobby after home improvements. That is gold prospecting, a past-time that takes him to goldfields all over Australia.

With all the solitude and fresh air, it’s balm for the soul, a little like fishing. The difference being that when you catch a gold nugget, you can sell it for cash.

And if you don’t land any nuggets, you can buy plenty for cash from someone who did. Maybe it’s the perfect smother?