Lady Ann Rylah’s mysterious death sparked speculation in political, media and legal circles

When the wife of Victoria’s chief secretary died outside her grand Kew house, the investigation raised suspicions of political tampering that still loom a lifetime later.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They call it the Olds Mates’ Act. Friends in high places can make problems go away, even murder charges.

In March 1969, the wife of one of Australia’s most powerful politicians was found bleeding and comatose outside her grand Kew house.

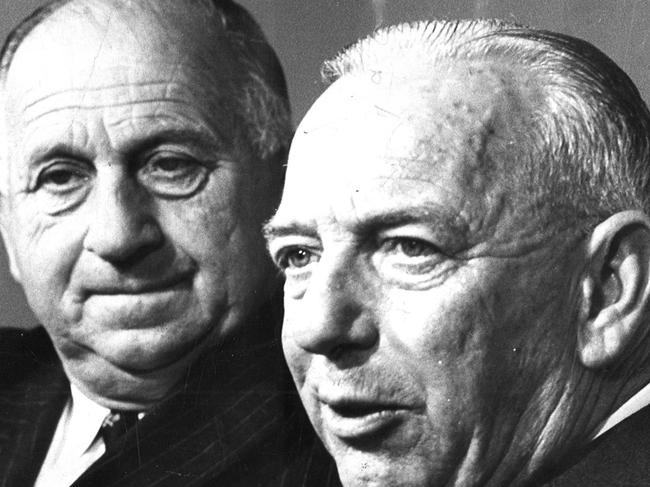

The injured woman, who died in an ambulance that morning, was Lady Rylah, wife of Victoria’s chief secretary Sir Arthur Rylah — longtime political henchman of premier Sir Henry Bolte and effectively the minister in charge of police.

At 58, Lady Rylah was an independent woman who practised as a veterinary surgeon at the Kew address under her own name, Dr Ann Flashman. She was a leader of the Girl Guide movement and wrote a newspaper column.

As a murder mystery — if that’s what it was — Lady Rylah’s strange death is intriguing, raising suspicions that still loom a lifetime later.

Two female kennel hands found their employer lying on a garden path just before 8am on March 15, a Saturday. Apart from tight-lipped police who cleared the scene, those two young women were probably the only witnesses with any idea how or when she might have suffered the injuries that killed her. They are probably alive but have never come forward.

Lady Rylah was dressed in her usual vet’s smock and slacks — but, strangely, had no shoes. It was almost as if someone had dressed her unconscious body but had forgotten the shoes, which were still at the back door.

Once she died, her body went straight to the old city morgue in Flinders St. Long-serving coroner’s pathologist Dr James “Mack the Knife” McNamara was asked to do a rushed post mortem. McNamara, a heavy drinker and pally with detectives, told the coroner, Harry Pascoe, the cause of death was a brain bleed.

Such bleeds can be caused by trauma such as a blow to the head, as implied by the dead woman’s wounds. In such circumstances, normally an inquest would be held to determine the official cause of death, but not this time.

On that Monday, barely 48 hours later, a small news story announced a cremation next day. After that, no-one could re-examine the body.

The homicide squad did not want to displease its political masters. Bent police who had flourished for years were under a cloud for taking bribes from illegal abortionists, and homicide chief Jack Ford and others would soon be dismissed in disgrace.

Of course, it was Ford’s men who stepped in to handle Lady Rylah’s sudden death to save embarrassment for Sir Arthur. It was clear her exit was hugely convenient for her husband, who’d been having an affair with the younger woman he would marry just months later.

Inevitably, the Rylah death sparked speculation in political, media and legal circles. Insiders would gossip for years about the coroner’s arbitrary cause-of-death ruling, unsupported by either a family doctor’s signature or an inquest.

Stretching his powers, the coroner swiftly signed papers ordering the cremation, ideal for anyone wanting to duck embarrassing questions an inquest might produce.

It would be almost a year before the irreverent journal Nation published an account of the facts under the headline “The Rylah affair and Kew”.

The story, unbylined to protect its author, revealed that Liberal branches were replacing Rylah as local candidate in coming elections.

The story revealed that Lady Rylah, wealthy in her own right, had changed her will six months before her death. The new will cut out her husband, leaving the Kew house to her daughter, a country property to the Girl Guides, and most of her estate to her son.

A clause in the will stated: “I wish my husband to recognise that the omission of any provision for him in this my Will arises directly from his abandonment of our marriage and reflects no ill will or resentment on my part.”

Perhaps she had just a little ill will. She told a reporter who had called the Rylah home in 1968 looking for her husband: “Don’t call me — call his slut!”

Rylah married his lover Ruth Reiner eight months after the funeral. But, only a year later, he collapsed with a brain haemorrhage, was in a coma for months and died an invalid.

That might be karma. But it doesn’t always go like that, as shown by the society scandal known as the “needle in the heart murder.”

It happened one night in late 1969, when respected Sydney surgeon and war hero Dr James Yeates was beaten around the head and stabbed in the heart with a hypodermic syringe of adrenaline in his garage in Vaucluse.

Dr Yeates’ wife, Diana, found his body. She then found solace in the arms of her lover, Dr Eric Hedberg, a family friend whose own wife had mysteriously died five months earlier.

Unsurprisingly, suspicion fell on Dr Hedberg. Surprisingly, despite overwhelming circumstantial evidence, he survived a coronial inquest into the Yeates death without being charged — and was never questioned over his wife’s death.

Not only had Joyce died suddenly after telling friends about her husband’s infatuation with Diana Yeates, but Hedberg demanded her body be cremated just two days later.

Ultimately, no one was charged over either death and, in 1964, Eric Hedberg and Diana Yeates married. They moved to a country town after Hedberg’s city practice lost popularity. But those who missed Jim Yeates and Joyce Hedberg never forgot the crime(s) behind the love story.

It wasn’t until Hedberg died in 2001 that Jim Yeates’ friends and family could speak openly to crime writer Candace Sutton, whose father had known Yeates. But, even after 40 years, some refused to break their silence.

Sutton’s revealing book, The Needle in the Heart Murder, paints the scene outside the coroner’s court in late 1960, when the worried widow arrived flanked by the best (and best-connected) lawyers money could buy.

One was Gordon Samuels, later Governor of NSW. Another was future judge Victor Maxwell. Her solicitor was Stan Howard, brother of future Prime Minister John Howard.

Diana’s lover Hedberg was also well represented, notably by Donald Stewart, later head of the Royal Commission into the Mr Asia drug syndicate and of National Crime Authority.

Hedberg, regarded as a mercurial surgeon willing to take chances, happened to be a nephew of Australia’s 11th Prime Minister, Sir Earle Page.

Sutton writes that detectives on the case were “confronted with a felony committed in the ideal place to keep secrets: within the bastion of the city’s ruling class.”

No matter what damning facts police and reporters uncovered, they didn’t seem to sway the city coroner, C.S. Rodgers.

Under the old NSW Coroners Act, Rodgers was the last coroner in that state with the power to decide whether suspects should stand trial. In this, his last big inquest, he chose to make a finding that Jim Yeates had been killed by a person or persons unknown — despite strong circumstantial evidence implicating Eric Hedberg.

Rodgers would retire soon after. The whiff of cronyism fed suspicions that justice had been nobbled. This accelerated moves to update the ancient Act and recruit coroners with legal expertise.

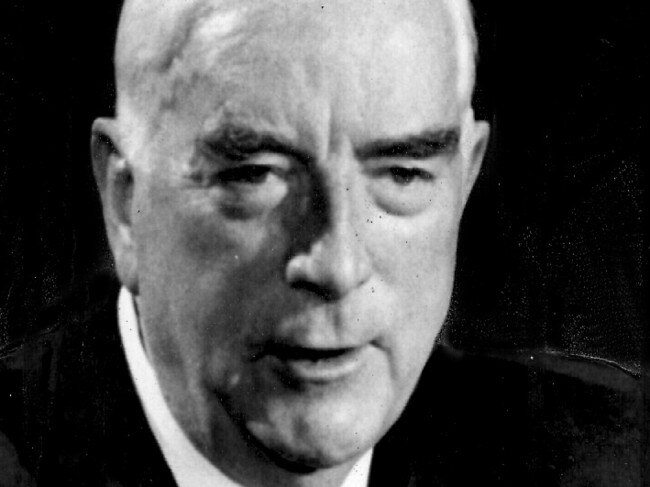

The spectre of heavy legal and political figures tampering with justice loomed over Victoria in the late 1920s, when the brother of future Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies used his position as Crown Solicitor to help a Mitcham orchardist extremely lucky not to be charged with wife murder.

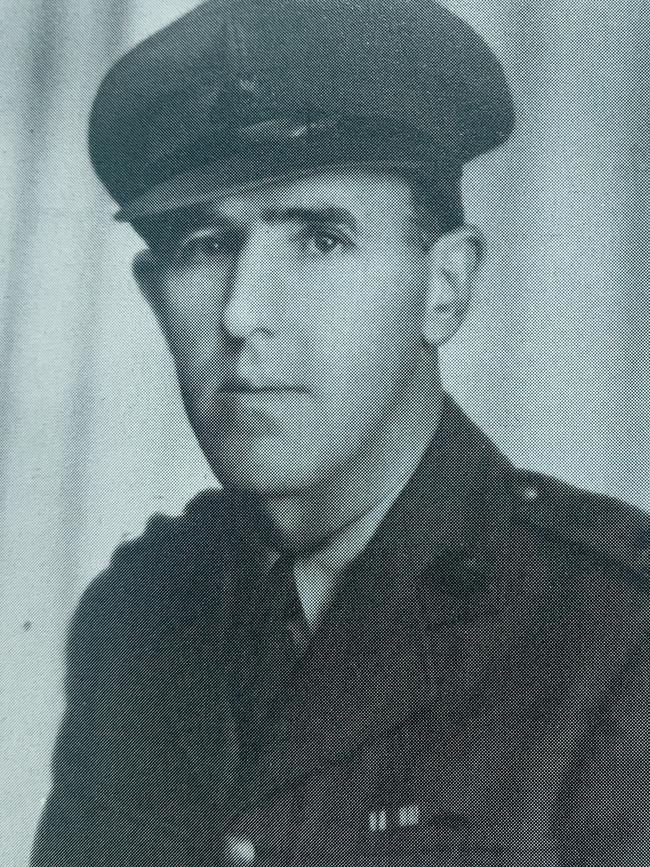

The Crown Solicitor was Frank Menzies, a former World War I officer. The orchardist was Ted Sampson, a returned soldier who happened to be the Menzies brothers’ first cousin.

It seems Menzies was willing to see another man stand trial for the murder when the only evidence pointed rather more towards Sampson’s involvement.

It happened after midnight on January 3, 1928. Sampson would claim later his wife Iolene had got dressed to come outside and hold a torch for him while he changed a flat tyre on his truck before leaving at 3am to cart fruit to the Melbourne wholesale market.

It seemed an odd story. Sampson later admitted that the tyre had been flat for days. Also (as would be revealed) his wife was dressed rather too well, including make-up, just to go outside to hold a torch briefly.

Around dawn that morning, around 5am, well after Sampson had gone to market, a young neighbour named Ernest Kleinert found a woman bleeding and unconscious on the road near the Sampson house.

Kleinert, whose parents kept an orchard opposite Sampson’s, ran to the house of the local policeman, saying he had tried to carry the injured woman, but she was too heavy. This explained the blood on his clothes.

Const. Bert Hanlon went with Kleinert. They found the woman in a pool of blood with a bad head wound. She was naked from the waist down and had blood between her thighs.

It looked like an assault. By the time Iolene Sampson died in hospital later that day, it was a murder. But who did it?

Press and police reports stressed that Iolene had been attacked while her husband, a respected returned soldier, was away from home. This invited assumptions that someone else was responsible.

Easiest to blame was Kleinert, the good samaritan who said he’d got blood on himself trying to help the victim.

But details emerged that pointed more towards the husband, Sampson. Police drained his farm dam a month later and found his axe, which Sampson had not reported missing.

Kleinert’s parents went broke hiring the best barrister they could, Eugene Gorman KC. Court proceedings were launched with undue haste, perhaps because of the influence of Sampson’s friendly cousin, Crown Solicitor Menzies.

There was no real evidence to support Kleinert’s guilt. But there was evidence that seemingly contradicted Sampson’s version of events.

Interestingly, Sampson tried to attack Kleinert outside court. There seemed to be a deep mutual animosity quite apart from the fact that one was charged with killing the other’s wife.

Evidence was led that the police chief commissioner, the former General Thomas Blamey, had threatened to cancel the police pension of an ex-detective working for the defence. Blamey, who’d later be sacked over another scandal, was close to Menzies.

Kleinert could easily have hanged for murder if one stubborn juror had not “hung” the first jury. Kleinert was acquitted at a second trial.

The evidence suggests the usual: that the murder was committed by someone close to the victim. Such as her husband, the man with the murderous temper who later that year wounded Kleinert with a knife after Kleinert called him a “bastard.”

Sampson should have been tried for attempted murder but was fined only five pounds for assault. Another case of help from friends in high places.

Each man lived until the late 1970s. Did one nurse a secret to the end? Or did both?