Decades old mystery: Why the death of Lady Ann Rylah still raises questions in Victoria

A “HAUNTED” mansion with a name scratched on a window. A secret door. A society sex scandal. What really happened to Lady Rylah?

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AS a murder mystery — if that’s what it was — the strange death of Lady Rylah has the lot. A “haunted” mansion with her name scratched on a window, a secret bedroom door and a society sex scandal.

Ann Rylah was remarkable in her own right — one of Australia’s first female veterinarians, bustling mistress of her own practice, a leader in the Girl Guide movement.

Under her own name (Dr Ann Flashman), Lady Rylah treated animals and wrote popular pet books — and a newspaper veterinary advice column under the name “John Wotherspoon”.

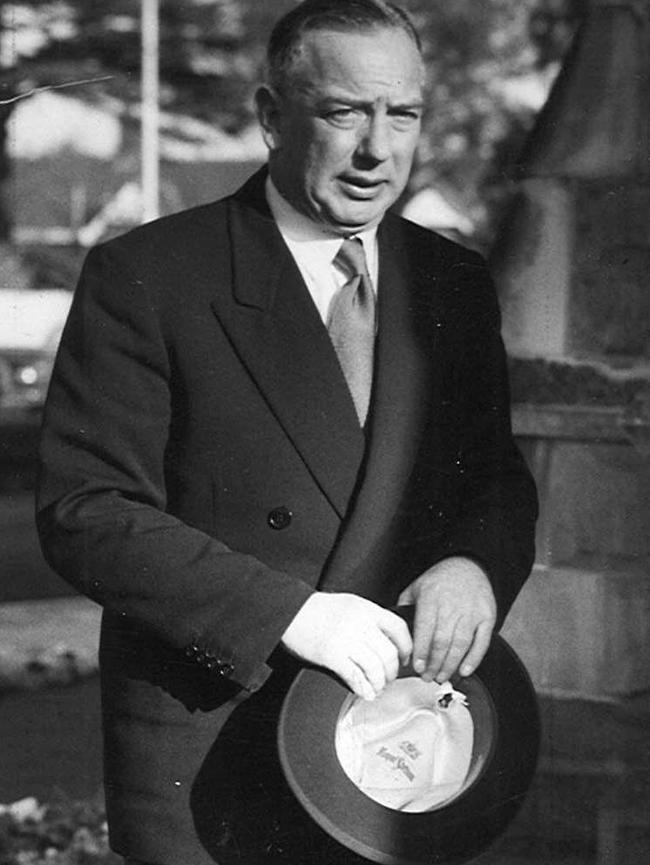

But she was also the bitterly estranged wife of one of the nation’s most potent political operators, Sir Arthur Rylah, who as Victoria’s Chief Secretary oversaw senior police and coronial staff.

Rylah’s power was one reason the circumstances of his wife’s death at her Kew house in early 1969 leaves suspicions that have lingered for decades. It reads like a plot from the classic police series Homicide, right down to the brisk detectives who came to Kew to sort things out.

The drama began at 7.50am on March 15, a Saturday, when two female kennel hands arrived to help with the dogs under Dr Flashman’s care. They found their employer unconscious in the backyard.

Those young women would now be close to 70, if still alive. Apart from the police who cleared the scene, they were probably the only witnesses with any idea how their formidable boss might have met her end.

Although it was early, Dr Flashman had apparently been outside some time, perhaps hours. She was lying about six metres along the concrete path between the back door and the kennels kept as part of the practice she ran from the double-storey house at 15 Victor Ave.

Blood had congealed around a head wound. She was dressed in her vet’s outfit of white slacks, smock and socks. Oddly, she wasn’t wearing shoes: her usual work pair sat neatly by the back door.

Had this most proper and methodical person carelessly walked outside in her socks — or had she been carried there by an unknown assailant? If so, forgetting the shoes might be the sort of mistake easily made by an offender rushing to “dress” the body (and the scene) to suggest some sort of outdoor fall to disguise a violent assault.

Not that the missing shoes seemed to matter to the tight-lipped police who took control of the scene after an ambulance picked up the comatose woman. The ambulance officers did not know who the patient was. She died on the way to St Vincent’s and the body went straight to the City Morgue, a grim place in the far west end of Flinders St.

It was Saturday but the long-serving coroner’s pathologist Dr James “Mack the Knife” McNamara answered the call. He did a post mortem immediately, informing the coroner, Harry Pascoe, that the cause of death was a subarachnoid haemorrhage — a brain bleed.

Such bleeds can be caused by high blood pressure, exertion or trauma such as a fall — or a blow to the head, which was consistent with the wound. Normally, an inquest would be held to determine the most likely cause.

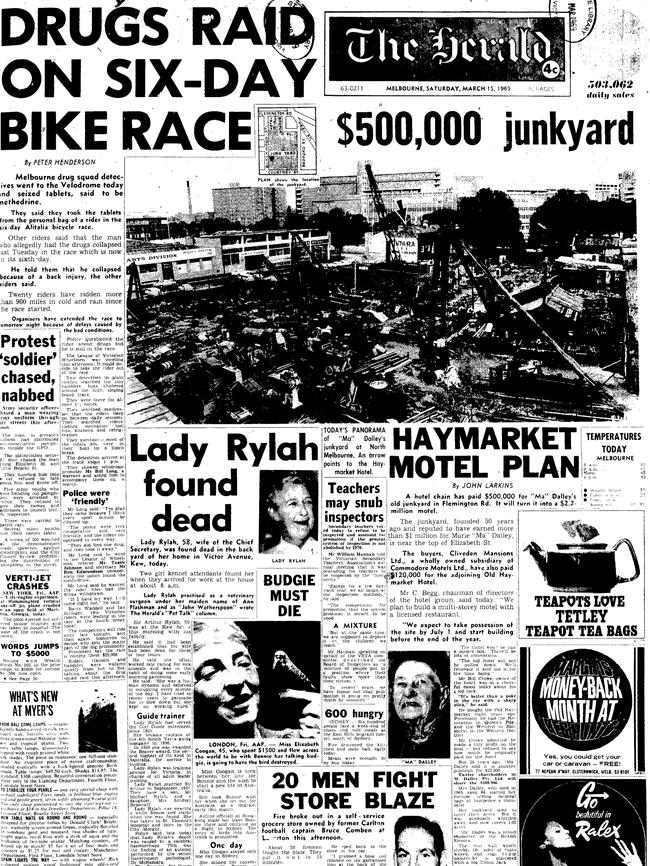

Lady Rylah’s death was front page news in that afternoon’s Herald. Neither the detectives nor the kennel hands were named but it was widely held that a notorious homicide inspector, Jack Ford, ensured minimum embarrassment for Sir Arthur, whose ministry controlled police and coroners.

With no new details to add to the story, it withered fast. On Monday morning, a few obscure paragraphs announced a funeral and cremation the next day. Nothing to see here.

That’s how the death of the estranged wife of one of Australia’s most powerful politicians was left.

Lady Rylah was not like most political wives of the 1960s. At 58, with her personal achievements and powerful personality, she was as well known as her husband, who had been 20 years in state parliament and was right-hand man to the all-powerful premier Sir Henry Bolte.

Rylah the city lawyer played the velvet glove to Farmer Bolte’s iron fist. But the man who had spent five years fighting the Japanese in World War II was tough, too, and shared a reputation for hard drinking every day. State politics reporters marvelled that Rylah drank brandy at morning press conferences.

Sir Arthur’s rank and reputation made it inevitable his wife’s death spawned speculation in political, media and legal circles. Insiders gossiped for years about the coroner’s arbitrary ruling on cause of death.

In ordinary cases, cause of death would either be formally provided by a family doctor — or established by an inquest. In this case neither happened.

Stretching his considerable powers, the coroner signed papers ordering a cremation, which happened just three days later — conveniently for anyone keen to avoid embarrassing questions an inquest might throw up.

And there were plenty of embarrassing questions to be asked, according to the moral codes of the time. But it would take 11 months before the irreverent journal Nation, published in Sydney, aired them in an unblinking account of the known facts.

The Nation piece was headlined “The Rylah affair and Kew”. The double meaning of “affair” hinted at the sort of gossip avoided by respectable media. The story, not bylined to protect its author, opened by stating that Kew’s Liberal branches were meeting the following week to try to replace Rylah as local candidate in the coming elections.

“The East Kew branch has asked him to stand down, for reasons it declines to specify,” the story read.

Nation revealed what had spooked scandalised Liberals into trying to ditch their distinguished local member: Rylah had in fact left the family home before his wife’s death because of his affair with a younger woman, Ruth Reiner.

Then there was the juicy fact that Lady Rylah, wealthy in her own right, had changed her will six months before her death to cut out her husband, leaving the Kew house and some money to her daughter Annabel, a country property to the Girl Guides, and the rest of her considerable estate to her son Michael.

A clause in the will states: “I wish my husband to recognise that the omission of any provision for him in this my Will arises directly from his abandonment of our marriage and reflects no ill will or resentment on my part.”

In truth, she might have had just a little ill will towards the man who had left her for the woman soon to become the second Lady Rylah. Journalist Evan Whitton, then of the racy Truth newspaper, recalls a reporter phoning the Rylah home in 1968 to ask for Sir Arthur and being told: “Don’t call me — call his slut!”

The man Whitton referred to in print as the “sodden and sinister” Rylah married Ruth Reiner the same year — eight months after the funeral. If he found happiness, it didn’t last. A year later, he collapsed with a brain haemorrhage, was in a coma for months and died an invalid just three years afterwards.

Rylah’s daughter Annabel Brownell disliked the Kew house with its secrets and its sorrows. She sold it to the first of a series of owners who tended not to live happily ever after.

A prominent criminal lawyer sold the house after his marriage ended in disaster, and the couple who bought it from him lasted barely three years before they, too, split up and left.

“It had bad vibes,” said a past owner, an Englishwoman with no idea of the house’s history when she’d arrived.

“The first night I was there I woke up at 3am thinking someone was sitting on the bed. The TV and the shower and the outside lights used to turn themselves on. In the end, I disconnected the outside lights.”

Owners noticed that Ann Rylah had scratched her name into the bedroom windowpane and they wondered at the hidden door leading through a cupboard into a smaller bedroom. Was it built so the Rylahs could pretend to sleep together long after they no longer did? And it was hard to ignore the neighbourhood rumours that Lady Rylah had “fallen on a spade”.

Lindsay Brownell, who married Annabel Rylah, is now in a suburban nursing home. His memories of his in-laws are fading but he recalls Sir Arthur moving in with him and Annabel before Lady Rylah’s death to hide the fact he was seeing “the mistress — Ruth Reiner”.

If the old house has secrets they have died with the main players, notably the pathologist McNamara and the coroner Pascoe. Among these silent witnesses was Insp. Jack Ford. The year after the Rylah affair, Ford was jailed for his part in the abortion racket that had made him and other corrupt police keen to stay “sweet” with Rylah.

The abortion racket inquiry made it hard for homicide detectives to handle dubious deaths at their own discretion. A now-retired policeman who was a constable in 1969 comments: “The homicide squad could write off anything they liked in those days.”

If there was foul play, the trail went cold long ago. Perhaps it was meant to.

The Victorian State Library has some 20 bound volumes holding every copy of Nation published from 1958 to 1972. But the one containing the damning Rylah article is missing. Librarians wonder if it was stolen long ago, leaving no other copy available in Victoria.

It could be coincidence. Or a case of making sleeping dogs lie.